Many powerful men would reside in Refugio or be involved in its politics. In fact, Sam Houston attended the 1836 Convention as a delegate from the Refugio Municipality, as well as James Power, the empresario. The delegates to the 1836 Convention drafted and signed the Texian Declaration of Independence. Further, Refugio had four delegates to the 1836 Convention, two being Power and Houston, while the others, David Thomas and Edward Conrad, were from a volunteer militia that insisted on having their own delegates to the municipality.1

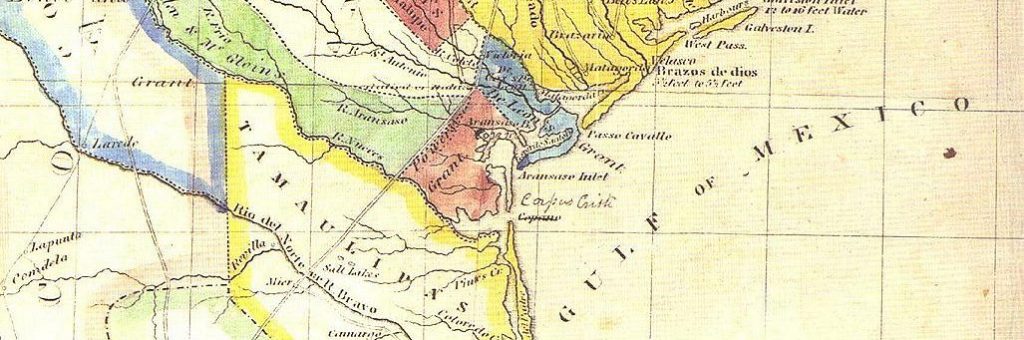

Refugio colonists were instigators and participants in many important mobilizations against the Centralist Mexican government. In fact, one of the first assaults led by Texians against Mexico was the raid on Lipantitlan, led by Refugio colonists James Power, Ira Westover, and James Kerr. James Power’s brother-in-law, Francisco de la Portilla, also accompanied them as a guide. Lipantitlan was a center of control for Mexican centralists in the San Patricio colony, which was another Spanish land grant settled by the Irish. James McMullen and John McGloin were the two Empresarios of the land grant, and so the San Patricio municipality is often referred to as the McMullen and McGloin colony in history preceding the Republic of Texas. By leading an assault on Lipantitlan, Texian volunteer soldiers removed Centralist influence in the San Patricio municipality, which was populated by many Mexican Federalists and Anglo Federalist sympathizers. The conquest of Lipantitlan also provided another layer of defense from the Centralist army of Santa Anna for the Texian garrison at Goliad, and by extension, the port at Copano Bay, which was a major port for Mexican and Texian commodities throughout the 1800’s.2

While many important people passed through Refugio or even resided there throughout the Texas war for independence, it was also the site of many unfortunate military blunders that cost the early Republic of Texas dearly. James Grant, a Scottish immigrant to Mexico, had invested immensely in Matamoros. Because of the rapid intensification of Mexican relations with Texians, Grant wanted to lead an expedition against Matamoros to protect his investments, which he was afraid would be expropriated in his time away from Mexico. Gaining the support of Phillip Dimitt, Frank Johnson, and Governor Henry Smith at the 1835 Convention, Grant advocated immediate action against Matamoros. He usurped Houston’s power as Commander-in-Chief of the Regular Army, and began gathering in Goliad and Refugio, where Colonel Fannin assumed Houston’s rank, arriving through the port of El Copano. To make matters worse, Grant stripped the Alamo of provisions, which he took to supply his self-interested expedition to the Matamoros.3

Later, prior to the Battle of San Jacinto, Col. James Fannin sent Captain Amon B. King and Captain Ward to rescue the colonists of Refugio from the approaching army of General Jose Urrea. On the way to Mission Nuestra Senora del Refugio, where the Refugio colonists had closed themselves in, Ward and King had a strategic disagreement and took their troops separate ways. King wished to punish a band of local rancheros who, because of bad treatment by American volunteers in the Texian Volunteer Army, had remained loyal to Mexico. Ward, wishing to follow orders and accompany the townspeople of Refugio back to Goliad, split ways with King. Their disregard for orders and the splitting of their troops resulted in their capture by Urrea’s men on two separate occasions. Meanwhile, Col. Fannin awaited Ward’s and King’s return patiently at Goliad, prepared to rendezvous with General Sam Houston in Victoria. However, King and Ward did not return; Fannin’s delayed arrival in Victoria resulted in its capture; and Dimitt’s Landing, an important sea port on Lavaca Bay, was apprehended. The citizens of Refugio, along with Ward’s men, were marched to Goliad where most were killed in the Goliad Massacre on March 27, 1836.4

While the role of Refugio was not significantly positive, neither was it significantly negative. However, for better or for worse, the combined impact of the strategic and political movements within and resulting from the Municipality of Refugio was of great influence to the course of the Texian war for independence.

- “Declaration of Independence of Texas, 1836 | TSLAC,” accessed September 27, 2016, https://www.tsl.texas.gov/treasures/republic/declaration.html.; William E. Dunn, “The Founding of Nuestra Senora Del Refugio, the Last Spanish Mission in Texas,” The Southwestern Historical Quarterly 25, no. 3 (1922): 174–184. ↵

- Stephen L. Hardin, Texian Iliad: A Military History of the Texas Revolution, 1835-1836, (University Texas Press 1994), 14, 17, 43-44. ↵

- Stephen L. Hardin, Texian Iliad, 106-110. ↵

- Stephen L. Hardin, Texian Iliad, 175-176; Hobart and Roell Huson, “King, Amon Butler,” June 15, 2010, https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/fki15. ↵

2 comments

Christopher Ezelle

James Power is my 3rd grandfather. You provided some good sources. I love to hear about my relatives and the times they live in. – Chris

Matthew Swaykus

I was surprised to read that this one town, Refugio, could have seen such iconic figures as Sam Houston or had influenced events such as the Goliad Massacre or the Battle of the Alamo. It is extremely interesting to see one town affect possibly tens of thousands of lives in this way. The author does a good job of detailing the ever-complicated interests that individuals and groups had and who they ultimately sided with in the war.