After watching the current events of this 2016 election, the American people can agree as a whole that this Presidential race has been significantly different than ones we have seen before. The two candidates take and give personal blows to each other, and the electorate watches as what seems as the most personal election in recent history. With careful consideration of previous American Presidential Elections, one might be reminded of another election just as personal, maybe even more so, than our current one. The Election of 1800, or as Thomas Jefferson put it: the “Revolution of 1800.”1

This gruesome election was between Federalist and incumbent John Adams with his running mate Charles C. Pinckney and Democratic-Republican and principal author of the Declaration of Independence Thomas Jefferson with his running mate Aaron Burr. In this story we have an interesting cast of characters, all of which are very prominent figures in the history of the early Republic. The men involved had intricate personal relationships that acted as a catalyst in the crucible that would become the Election of 1800.

All men involved came from some form of political or military merit. John Adams was a prominent voice in declaring America’s Independence. Thomas Jefferson had been the United States Minister to France (he had spent a majority of the war and its aftermath in France). Aaron Burr had been a colonel in the Continental Army. Most of the men were quite fond of each other due to the fact that they had worked with each other before, although all had one thing in common: their distaste for Alexander Hamilton, Chief de Aide for General George Washington during the Revolutionary War and Senior Officer in the Continental Army. Hamilton was a stubborn man. Years before the election Hamilton had attempted to destroy Adams in his Adams’ Pamphlet, 2. He continuously bashed heads with Jefferson, while both he and Jefferson served in George Washington’s Presidential Cabinet in the early 1790s; and Hamilton was very vocal in his distaste of Aaron Burr.

At the beginning of the race, much of the American population was not too fond of President Adams’s Administration. With the implementation of the highly unpopular Alien and Sedition Acts, which was an act of law signed by Adams himself in 1798 that allowed the deportation of foreigners, the Federalist party itself seemed to fall apart. Only some truly supported Adams. With the relative unity of the Democratic-Republican Party and the particular favoritism of Jefferson in the South and Aaron Burr in New York, the Federalists feared that their opponents would win the presidency. In November of 1800 the election began, and as the ballots came in, the results only surprised a few. Adams received sixty-five votes while Jefferson received seventy-three. The election seemed to have been won, but something went wrong. The members of the electoral college failed to hold back one of their votes for Burr, which caused a vote count tie of seventy-three votes for each Jefferson and Burr, and thus propelled the two into a one on one race for presidency. 3

Alexander Hamilton, seeing both of his enemies with the potential to become president, felt himself in a sticky situation. Adams seeing this, laughed at Hamilton, saying,“The very man—the very two men—of all the world that he was most jealous of are now placed above him.”4 Hamilton had to put his pride aside and place his support behind one of these men for the betterment of the country.

Aaron Burr, being Jefferson’s running mate, was also put in an uncomfortable situation. He came into the race as just a Vice Presidential candidate; now he had to go against Jefferson for the presidential seat. Most people believed that Burr should just give Jefferson the position, even if Burr might have won by a landslide in the coming vote in the House, where the tie would be decided. This was not Burr’s intention. After being Jefferson’s running mate in the previous election, the Election of 1796, Burr had been left with a bitter taste in his mouth after Jefferson himself won the Vice Presidency and left him with nothing in fourth place. Burr even went so far as to say “As to my Jeff, what happened at the last election (Et tu Brute!).” 5 Burr was in it to win it.

Now that Adams, the Federalist Presidential Nominee, was out of the picture, the Federalists were in a scattered frenzy over whom they should pick: Jefferson or Burr. Most contemplated giving their votes to Burr due to the fact that most Federalists saw Jefferson as unfit to run for such an office, or as Robert G. Harper, a Federalist, put it: Jefferson was possibly able to be “a professor in a college or a president of a philosophy society,” but definitely not the head of our nation. 6 Others that were in favor of Jefferson were known to be quite violent in their advocacy, some even stating that if Burr were elected in place of Jefferson “we will march and dethrone him as an usurper.” 7

Finally, in February of 1801, the voting went to the House of Representatives. All sixteen states were allowed a single vote, and the winner only needed a majority of nine votes. The voting went on for five days. Tensions rose, state militas threatened to rise if a president was not elected. The House went through thirty-five votes, and each time they reached the same result: a tie. Then men grew restless and began to seek out an easy way out, and this is when Hamilton seized any opportunity he could to write to each of his Federalists colleagues in the electoral college to either withdraw their vote or place it for Jefferson.

James A. Bayard, a Federalist from Delaware, began to listen to Hamilton’s plea. For all thirty-five previous votes, Bayard had voted for Burr, but after reading Hamilton’s letters, Bayard began to weaken his support for Burr. Finally on the thirty-sixth vote, Bayard inserted a blank vote and abstained Delaware’s vote. At the same time two other representatives gave in as well and also withdrew their votes, allowing Jefferson to win ten votes, and thus win the presidency.

The general confusion of the Election of 1800 led the next Congress to pass the Twelfth Amendment, which revised the way the electoral college elected the President and Vice President. In addition to the passing of the Twelfth Amendment, personal feuds came to fruition after Burr’s lost. Burr believed Hamilton was the greatest impediment in his path for success and challenged him to a duel. In 1804, both left to New Jersey and Burr shot down Hamilton.

- Alan Brinkley, American History: Connecting with the Past. Volume 1: to 1865 (New York: McGraw-Hill Education, 2015), 177. ↵

- Ron Chernow, Alexander Hamilton (New York : Penguin Press, 2004), 619. ↵

- Brinkley, American History: Connecting with the Past, 178. ↵

- Chernow, Alexander Hamilton, 632. ↵

- Chernow, Alexander Hamilton, 634. ↵

- Chernow, Alexander Hamilton, 634. ↵

- Chernow, Alexander Hamilton, 635. ↵

84 comments

Travis Green

Very interesting and informative article. It’s nice to have all of the insanity and craziness that was the revolution of 1800 wrapped up in one neatly packaged article. It’s always interesting to me that political discourse has remained relatively the same after all of this time. It’s great to think about now because I never really paid attention to or cared about this story until now. So kudos for that.

Edgar Cruz

I absolutely love this article due to the example that this situation between Burr and Jefferson can relate to the more modern elections, like the 2016 election. A lot of the times when we are reading about early history in the US it can be extremely difficult in order to understand or relate to it. The example helped me enjoy, more, the events that transpired in this article.

Elliot Avigael

Wow, it’s absolutely amazing to think that nothing’s changed when it comes to the ferocity of our elections. Tensions are still just as high now as they were in 1800, and after the 2020 election, there’s been a growing sentiment in which people on both sides of the isle don’t even know if their votes count anymore. I always thought ugly campaigns and personal attacks were a thing of present day, not of the past.

Impressive.

Sabrina Drouin

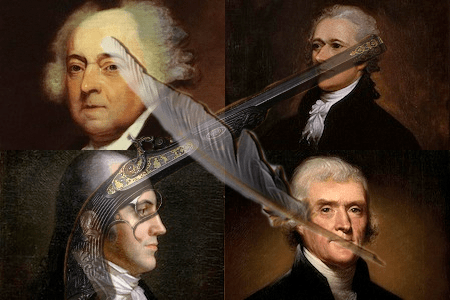

Great article, I really liked all of the photos you included that really helped me put a name from the article to a face in the images. I always wondered how they resolved this tie and what ended up happening to Hamilton and why people relied so heavily on Alexander Hamilton’s word but he never became president, even though people relied on his word. I think that this was one of the most cutthroat elections ever to happen and I’m glad you put a spotlight on it and how it ended in Hamilton being shot and our 12th amendment.

Maria Luevano

I really enjoyed reading this article. I did know the election of 1800 is an important time in history for the United States, but I did not realize how messy and disorganized the process of this election was. It surprises me that of all people Hamilton can be credited for breaking the tie between these two candidates. The ending, however, is the most interesting part to me. I did not realize the states were even allowed to withdraw votes and does not seem like a logical answer to the problem.

Christopher Metta Bexar

Before reading this article, I had only really heard of Aaron Burr as the man who had killed Alexander Hamilton. His position in history was mostly unknown to me.

The portraits of the four men most involved in the election of 1800 illustrates more clearly the lives of the early founding fathers as well as a reminder that Hamilton was able to put the needs of the country ahead of his personal gain or ego.

Trenton Boudreaux

A very well written article on what looks to be an extremely heated election. It’s amusing to think how a flaw in a voting system could result in this entire second electoral race, just for Jefferson to win again in the end. I could not imagine this sort of election happening today, although we have gotten very close with our previous two elections.

Carlos Hinojosa

Your article did an amazing job on showing the chaos of the Election of 1800 showing how the rising tensions between both parties finally ended after the election but only due to the Federalist’s parties decline. The article also did a good job presenting what happened after the election and how the tie was solved with both parties help.

Tyler Pauly

This article was very interesting because I think it tackles an issue that most people would somewhat overlook. It isn’t too often that we learn about an actual election race rather than just the results. I wonder if that’s because very few races are very interesting or because they are just simply overlooked. Regardless, this race was definitely important as it led to an accidental tie that would eventually lead to two important historical events in the 12th Amendment and the rivalry between Burr and Hamilton.

Phylisha Liscano

Hello Roberto, I very much enjoyed reading your article. It was very interesting and entertaining to read. I had never really put in any attention into this story until now and you made very easy to follow. All of the images you provided allowed me to get a visual of each man. I can see how there’s was so much stirred up during The Election of 1800. Hamilton played a big part in this election, his actions resulted in Jefferson winning the presidency.