During the nineteenth century, London was riddled with crime and corruption and the district of Whitechapel was filled with prostitutes and crime. To worsen matters, the police force was weakened due to the inefficiency of those in charge. As a result, the home secretary sought to appoint former soldier Sir Charles Warren as Chief Commissioner of the Metropolitan police force. It was not until March 1886 that Warren began his work as Chief Commissioner over all districts in London.1

Pressured by the widespread approval from the people of Whitechapel, Warren knew he had a lot to fix within the police force to stabilize the district. Warren’s first reform was manpower redistribution within police force division, specifically the addition of two divisions, F and J. In his following two years, he reinforced the importance of these two new divisions when he assigned more trained police officers to these divisions in attempt to create order in London’s districts.2

Although prostitution was quite common in nineteenth-century London, its legality resulted in neglect from police commissioner Warren. However, in 1888, Warren began to focus on the Whitechapel district in particular, due to the murder spree of Jack the Ripper, who had mutilated over seven prostitutes in five months. Commissioner Warren had to regroup officers from other divisions into the district of Whitechapel in an attempt to catch the killer.3

The investigation began with Martha Tabram, the first known victim of Jack the Ripper.4 Tabram was found dead on the stairs of a lodging house with thirty-nine stab wounds. Police reports concluded that one of her wounds was inflicted by a left-handed person, while the other lacerations on the body did not match the same stabbing pattern. The inconclusive investigation tore the police force apart. To worsen matters, Warren had no official statement for the public and the city grew unsettled. No crime as brutal as Martha’s had been committed in the East-end at the time. However, no one anticipated that Jack the Ripper would gruesomely slay two more victims within the next two weeks.

The second victim, Mary Ann Nichols, was found with her throat and abdomen split open in a yard by J division twenty-four days after Tabram was found. However, the Crime Investigation Department (CID) was unable to gather any evidence that could trace back to Jack the Ripper due to the interference of Warren’s H division constables. One of his constables was headed back to work when he stumbled across Nichols’ body and ran to the scene. Without thought, he tampered with the crime scene, but he was not the only one who broke division protocol that night. On the scene, the doctor observed the corpse’s wounds and ordered an unauthorized police officer to escort Nichols’ body off to a morgue. With the presence of only one amateur photographer and a dismissive doctor, the investigation photographs only captured Mary Ann Nichols with a white sheet over her face. Countless hours of investigation led up to little progress. Commissioner Warren doubted his ability to stop Jack the Ripper.5

The aftermath of the crime proved that the new division strategy Commissioner Warren had constructed was flawed. With no report or valid evidence, the people of Whitechapel felt unsafe, and uneasy towards Chief Commissioner Warren and his officers. Unfortunately, the murder of Annie Chapman happened a few days later, and caused panic for the Chief Commissioner. Chapman was found with her throat slit from left to right and her stomach split open, exposing her intestines. There was no strategy Warren could construct to apprehend Jack the Ripper. It was the beginning of a never ending goose-chase.6

With the continuous murders, Commissioner Warren knew he had to act quickly, but he wasn’t sure how to approach the situation. Warren was a man of action, but too caught up in his power to effectively lead. Distracted by public elections, Warren drifted away from the security of the Whitechapel district. Warren’s main focus was to gain the head detective position for the CID. When he was chosen to be the head detective, he ran the investigations in his own way without considering the opinions of his partners. Subsequently, the investigations he took part in led to a dead end, and on September 30, Jack the Ripper struck again.7

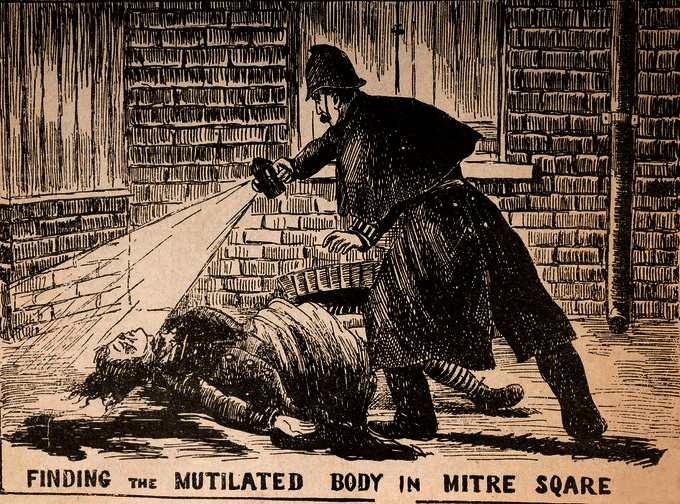

Twenty-eight days after Chapman’s attack, Jack the Ripper struck twice, mutilating the bodies of Elizabeth Stride and Catherine Eddowes. Both bodies were severely cut open exposing intestines and their throats slit from left to right. Eddowes’ body was missing a kidney and part of her ear. Her mutilated body became the worst case of homicide the police force had encountered to date. Violence escalated as the Ripper took more time mutilating the bodies. However, this time Jack the Ripper decided to start sending letters to the Whitechapel police, mocking their inability to catch him. Five days before the attack of Stride and Eddowes, the force received a letter in which the Ripper stated that he was just getting started with his work. The letters didn’t seem to satisfy the Ripper, so he sent out a special package. When the police force opened the package, they came across a kidney with a letter written in blood.8 Warren and several officers treated the letters as a hoax, but with Eddowes missing kidney, the fear grew among all of the men and the city.

Commissioner Warren quickly acted by enforcing stricter night watch for the officers to stake out the Ripper. But the neighboring communities and locals questioned their safety and the commissioner’s strength in the case. Soon, the Office of the Board of Works wrote a letter to Chief Warren in regards to his ineffective strategies and weak vigilance. There were plenty of citizen-written letters as well, some suggesting their own methods for strategically catching Jack the Ripper. One that stood out to Chief Warren was the use of hound dogs to track the Ripper as he attacked his next victim.9

October was a quiet month for the city of Whitechapel, with no activity from the Ripper recorded. In preparation for any unexpected acts, Warren gathered hound dogs to prepare for the next attack. Commissioner Warren hired Edwin Brough to take his dogs in order to train them for the mission he had prepared. Warren was sure he would get Jack the Ripper now. For several days the dogs would train by searching for Warren who was imitating the target. But the weeks passed and October remained slow with no murders.10 The town grew quiet, still in fear, but relieved while Warren felt defeated and out of place in his work. On the 8th of November, Commissioner Warren resigned, but remained part of the investigation until December of 1888.

After resigning, Commissioner Warren felt confident that the Ripper was finished with his work this time and released Edwin Brough with his hound dogs. Abruptly on November 9, Mary Kelly was the last prostitute mutilated, a conclusion to the Ripper’s murder spree. Kelly’s breast were cut off, naked with her guts out, elbow bent, and her faced hacked beyond recognition.11 There was not much to be done when they made a postmortem examination, but it was concluded that all the murders were committed by one man. All the fault laid on Commissioner Warren when the media and public addressed their hate towards his low quality leading and inability to catch the killer. Newspapers flooded the streets, all demanding the Whitechapel officers to explain what their next steps would be and if any evidence was found that could help identify the Ripper.

Unfortunately, Chief Commissioner Warren’s attempts to catch the Ripper failed, and those who had once praised him now poured public shame on him for his lack of effective leadership. Over time the investigation pool only held three contemporary suspects. The one that stood out the most was a Jewish man that went by the name Kosminski. Kosminski’s name appears in several detective annotations from the crime scene investigations and other police reports. One witness claimed to have noticed him taking part in a murder, but refused to testify against him due to his Jewish heritage and disapproval of capital punishment. Even though the murders stopped after the identification of Kosminski, the true murderer remains unknown to this day.12

- Scott Palmer, Jack the Ripper: A Reference Guide (Boston: Scarecrow Press, Inc, 1995), 65-68. ↵

- Scott Palmer, Jack the Ripper: A Reference Guide (Boston: Scarecrow Press, Inc, 1995), 65-68. ↵

- Neil R. A. Bell, Capturing Jack the Ripper (United Kingdom: Amberley Publishing, 2014), 125-127. ↵

- Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology, 2001, s.v. “Jack the Ripper,” by J. Gordon Melton. ↵

- Neil R. A. Bell, Capturing Jack the Ripper (United Kingdom: Amberley Publishing, 2014), 128-135. ↵

- Neil R. A. Bell, Capturing Jack the Ripper (United Kingdom: Amberley Publishing, 2014), 135-140. ↵

- Scott Palmer, Jack the Ripper: A Reference Guide (Boston: Scarecrow Press, Inc, 1995), 65-70. ↵

- Lee Lerner and Brenda W. Lerner, Crime and Punishment: Essential Primary Sources (Detroit: Gale, 2006), 99-101. ↵

- Neil R. A. Bell, Capturing Jack the Ripper (United Kingdom: Amberley Publishing, 2014), 190-200. ↵

- Neil R. A. Bell, Capturing Jack the Ripper (United Kingdom: Amberley Publishing, 2014), 200-220. ↵

- Neil R. A. Bell, Capturing Jack the Ripper (United Kingdom: Amberley Publishing, 2014), 225-243. ↵

- Neil R. A. Bell, Capturing Jack the Ripper (United Kingdom: Amberley Publishing, 2014), 153-230. ↵

60 comments

Briley Perkins

This article was very well written! I have not heard of Jack the Ripper before, so it was interesting to read what his story was. The fact that the Ripper still remained at large after all the precautions and investigations is insane when thinking about today’s crimes. They did not have the technology that we have today, but still it gets to a certain point.

Hannah Hennon

To me it is crazy to think that someone did all those murders and got away with it. Also, it is hard to think someone died getting away with it, so they never have to face punishment. It must have been difficult trying to catch a serial killer when forensics were not that great during that time. Plus Warren could not get his divisions straightened out fully.

Mitchell Yocham

Back then, when the police force wasn’t as strong, it was very easy to get away with murder because as long as you didn’t leave any obvious evidence, chances were the police wasn’t going to find you. However, because every murder had to do with prostitutes, commissioner Warren could have expended more of his night watch guards around prostitutes in order to protect them and have a slightly bigger chance of finding Jack the Ripper.

Sabrina Doyon

Wow, I have read the story of Jack the Ripper many times but this was a great one! I really love how he taunts the police and continues to spread chaos. The image of the mutilated body was wild and I was not prepared but it definitely adds some more depth to the overall tone of the article. This was a great read!

Mauro Bustamante

You also see how other serial killers in a later time kind of got their ideas from jack the ripper. He was an infamous serial killer in history, may people still know his name still today. The fact that most of his victims were prostitutes and the police, in my opinion really didn’t do anything because of their own fear. However, in my opinion if their were a killing spree like this today I believe that police today will have better chance with finding a serial killer like Jack, just because of the improved technology that exists today, which didn’t really exist then. this article was well written and informative about the topic.

Elizabeth Maguire

Before reading this article, I had heard about Jack the Ripper and some of his story and the deaths but not to the extent of this article. It is interesting that they were not able to find him. The pictures that was put in to the article were really interesting to me. Overall, this article was a very interesting article.

Vania Gonzalez

Jack the Ripper is one of the most infamous serial killers in history especially if you’re studying in a field of crime. You also see how other serial killers in a later time kind of got their ideas from jack the ripper. For example, Jack sent letter the police mocking them not being able to catch him later on in the 1970’s we see the Zodiac killer in San Francisco in a way copied him in those letters to the police mocking them not being able to catch him. Only the Zodiac killer sent the letters to the local newspaper.

Gabriella Urrutia

Although I had heard the name Jack the Ripper before, I didn’t know much details about him. It is very interesting to me that they were never able to find out who was the killer. It is not surprising that people were blaming commissioner Warren for not finding the killer but I feel like he didn’t deserve that much hate. It seemed like he was trying his best to find where the killer was.

Samantha Bonillas

I had heard about Jack the Ripper before reading this article, but not the details of his story and the deaths. The fact that most of his victims were prostitutes and the police, in a way, looked away from the case is absurd. Even if at that time the police were looked down upon, there were still people getting killed. Jack the Ripper could have gotten away with more murders if he hadn’t committed continuous murderers and sent letter to the police. Overall, good article.

Stephanie Cerda

I’ve heard about Jack the Ripper many times, and it’s still always interesting to hear what happened then. It does make me wonder if Jack the ripper would be caught a lot faster with today’s technology as well as resources. I do feel that the blame Chief Commissioner Warren is understandable coming from the public, since it’s expected for someone in authority to be able to protect others. Still, it’s hard to truly decipher how it all completely falls into his hands. They didn’t have much to go on, especially at that time.