Although it only lasted one year, in 1789, New York City was once celebrated as the first capital of the United States. Today, the city is recognized by many as the most densely populated city in America. In fact, the population of New York City at the 2010 census was 8,175,133.1 A remarkable city! If you have ever visited or have had the pleasure of living there, you would quickly realize that the makeup of the city is uniquely its own. It has proven to be one of the most racially and ethnically diverse region in the nation. Globally it is often considered one of the world’s leading commercial, financial, and cultural centers. New York City is subdivided into five boroughs coextensive with five counties of New York State. In descending order of area, the boroughs are Queens (Queens Co.), Brooklyn (Kings Co.), Staten Island (Richmond Co.), the Bronx (Bronx Co), and Manhattan (New York Co). Moreover, New York is a financial, commercial, manufacturing, and tourist center. Most importantly, as it pertains to this story, it is said to be a national focus of road, rail, water, and air transportation.2 With such a large community, it is easy to appreciate the need for mass transit there. If you have lived or traveled there, you more than likely could not and would not want to imagine the city without it! Now, imagine a city hiding an amazing secret beneath its streets — a circular train that rides huge gusts of wind traveling inside an eight-foot-wide tunnel. Does that sound like something from the future? Such a train actually operated in New York City in 1870, 140 years ago, thanks to the inventor and admirer of modern science, Alfred Ely Beach.3

In the early nineteenth century, city traffic in many urban centers was becoming an unmanageable, high-population-density nightmare. Narrow, twisting lanes and dead-end streets built for foot traffic and mounted riders were being confronted with increasing volumes of coaches, carriages, and omnibuses. The congestion became a major civic issue in population centers such as London, Paris, New York, and Boston.4 In the later part of the century, after the American Civil War, over seven hundred thousand people lived on the island of Manhattan; still, even more refugees and immigrants arrived daily by the thousands. New York City and its citizens were desperate for a solution they had never fathomed.A young innovator by the name of Alfred Ely Beach had a solution to improve the plodding and burdensome traffic situation. Alfred was the very well-educated son of inventor and publisher of the New York Sun, Moses Y. Beach. Much like his father Moses, Alfred Ely Beach made a joint investment with partner Orson Desaix Munn to purchase the Scientific American publication from Rufus M. Porter, just ten months after the creation of the publication.

On July 23, 1846, the partners printed the first edition of Scientific American with the primary focus of providing information regarding patented inventions, including the official list of patents approved by the U.S. Patent Office. When so many hopeful inventors asked for help with the patenting process and laws, the partners created a patent agency. Scientific American described the models of inventions their clients brought them, among them Thomas Edison’s 1877 phonograph. The thriving agency attracted major inventors, such as Samuel F. B. Morse, Captain John Ericsson, and Elias Howe. Much later, Albert Einstein would come to contribute articles to the popular publication.5 This was just one way the publisher and inventor helped stimulate nineteenth-century technological innovations while simultaneously producing one of the world’s most prestigious science magazines.6

Certainly, being raised by an inventor and working within this close proximity to many great technological pioneers, Beach was bound to have a mind full of ideas of his very own. Beach was most interested in inventions, and although he was the magazine’s editor, he devoted most of his effort to helping and advising inventors and to working on his own inventions. In 1847, Beach applied for his own first patent, on a typewriter, and a few years later, at the 1853 Crystal Palace Exhibition in New York City, he displayed a version of his machine that produced embossed letters for the blind.7 While this was a great accomplishment on its own, Beach sought to conceptualize an idea that would improve the lives of the masses.

All the while, Beach watched Manhattan’s streets growing hopelessly dirty and dangerous as four or five horse-drawn omnibuses rattled by each minute. He turned his attention to urban rail service.8 Beach drew inspiration from James Henry Greathead, the Englishman who had built London’s subway in 1863. This system, which Londoners called the Underground, was literally an underground railroad that ran on steam locomotives. These trains produced smoke, causing the subway passengers to cough and choke as they traveled beneath the city. At this time, London also used smaller subway tunnels to deliver letters and small packages. They were three-foot-tall pneumatic tunnels that blew air-powered mail carts to the post office in sixty-five seconds. Alfred was amazed at how England had solved its public transportation problems, and he was inspired by the cleanliness of the air-powered mail subways. After much thought, he had a brilliant idea. Beach combined these two ideas to design the first wind-powered passenger subway train. By applying an engineering method, pneumatic power, Beach wanted to create a cleaner underground subway system to alleviate some of the city’s congested streets. Would the urbanites accept his progressive idea? Would the city’s most prominent officials approve Beach’s proposal?9

Yet, there was a major obstacle in the way of Alfred Ely Beach realizing his dream of alleviating the public of the hazards that were New York City streets. The name of this obstacle: William “Boss” Tweed, New York State senator, Democratic Party boss, and head of “The Tweed Ring.” Sufficiently aware that he would need the state’s permission, Tweed presented a problem because of his ventures in an above-ground railway. He hoped the elevated train would make him rich, mainly through bribes and other illegal methods, all of which led to his imprisonment in later years. Tweed didn’t want any competition. Additionally, Beach knew that Tweed influenced the other members of the state legislature to oppose passenger subway construction.10 The Tweed Ring infiltrated nearly every segment of public life in New York City. The ring included the governor, the mayor, the city comptroller, and countless other prominent citizens in both the public and private sectors. It operated by granting municipal contracts to its political cronies and by embezzling funds intended for hospitals and charitable institutions.11

At the 1867 Fair of the American Institute in New York City, Beach exhibited a tube in which a ten-passenger car was driven back and forth by a powerful fan. Because of the opposition of Tweed and his interests in the omnibuses and street car lines, Beach found it necessary to construct an experimental subway in secret. Obtaining a charter in 1868 for a four-foot pneumatic tube to demonstrate mail delivery, he actually dug an eight-foot bore tunnel 300 feet under Broadway, between Warren and Murray streets. There is much debate on whether this was Beach’s original intention or—whether it was actually a smokescreen, a way to get authorization to build a subway system without letting the city of New York know what he was doing. In fact, the pneumatically-powered mail system was utilized for several years after Beach’s passing in 1896.

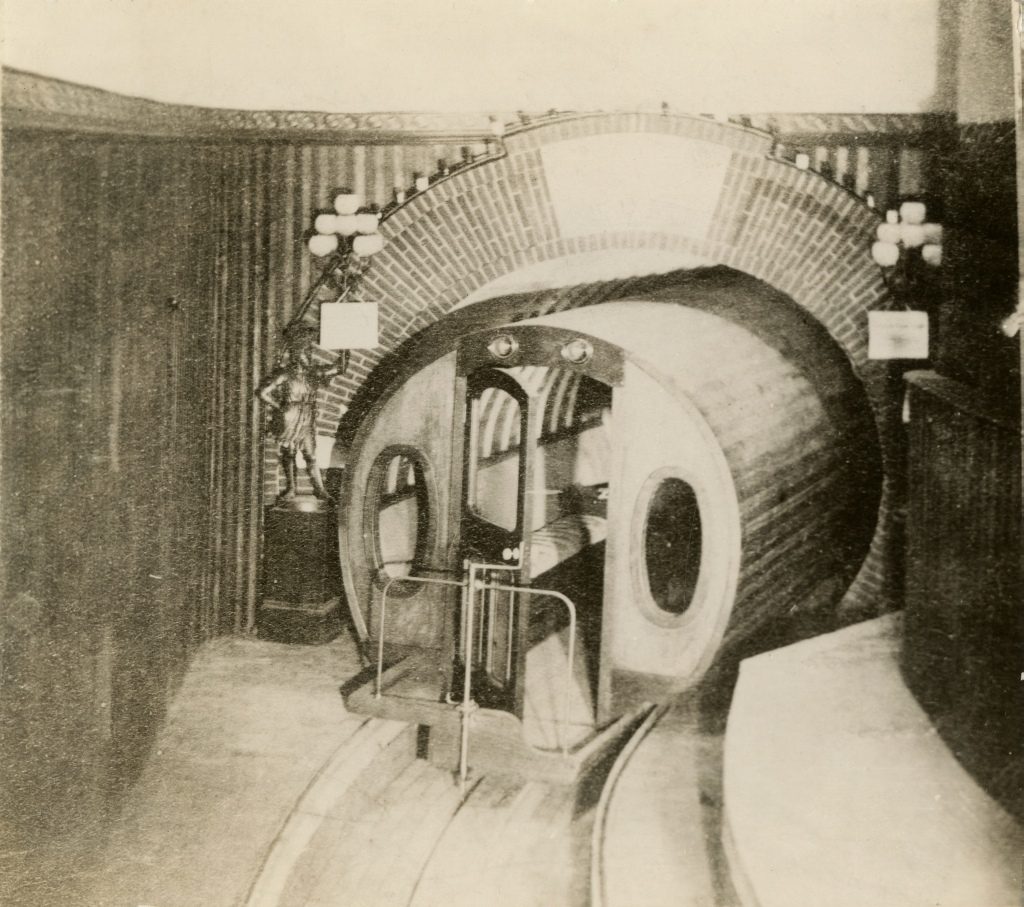

Commissioned by Beach, workers dug the tunnel secretly at night, carting away the dirt under the cover of darkness. They were constructing it right under the noses of officials at Manhattan’s City Hall, located just across the street. Workers used a specially invented shield to keep the streets above from collapsing on them while they excavated and then lined the tunnel with brick and cement. Hydraulic rams were installed to force air through the 312-foot-long, 9-foot-diameter tunnel and move a subway car. When the tunnel was completed, it became New York City’s first underground subway.12 The finished system had a single pneumatically-driven car that shuttled people between two sumptuous stations with paintings, frescoes, and fine furniture. To give an estimate, this proposed system could provide about four hundred thousand citizens transportation. In total, the cost of the project was $350,000, all of which Beach funded at his own personal expense.13 Once Beach finished his tunnel, he gave a gala reception on February 26, 1870, to which he invited city and state officials. He began demonstrating his system by giving rides in the eight-foot-long car that held twenty people. Each person paid 25 cents for the thrill of riding the underground car. The “fare” was later donated to charity, because Beach’s original charter did not give him the right to collect money. Newspapers published glowing reviews of the new system, noting its elegant reception room and light, airy tunnel.14

As for Boss Tweed’s opposition to the system, Tweed was said to be enraged when he learned of Beach’s sneaky invention, and more so probably due to the fact that he had not successfully extorted money from the young innovator. The famously-corrupt politician had failed to safeguard the interests of the omnibus and streetcar lines that paid for his patronage.

While Tweed dominated the Democratic Party, in both the city and state, and had his candidates elected mayor of New York City, governor, and speaker of the state assembly, the city kept a watchful eye. In 1870, he forced the passage of a new city charter creating a board of auditors by means of which he and his associates could control the city treasury. The Tweed ring then proceeded to milk the city through such devices as faked leases, padded bills, false vouchers, unnecessary repairs, and overpriced goods and services bought from suppliers controlled by the ring. Voter fraud at elections was rampant. Moreover, he was using this power to prevent Beach from moving forward with producing additional transit tunnels and passenger carts.15 Toppling Tweed became the prime goal of a growing reform movement. Exposed at last by The New York Times, the satiric cartoons of Thomas Nast in Harper’s Weekly, and the efforts of a reform lawyer, Samuel J. Tilden, Tweed was tried on charges of forgery and larceny. He was convicted and sentenced to prison (1873) but was released in 1875. Rearrested on a civil charge, he was convicted and imprisoned, but he escaped to Cuba and then to Spain. Again arrested and extradited to the United States, he was confined again to jail in New York City, where he died.16

Over all, Beach’s transit system was viewed more as a curiosity than as a practical device, especially since it never grew past its one short tunnel, two stations, and one train car. Although New York’s State legislature eventually gave Beach a charter to build a subway line, the economic Panic of 1873 made funding for the project unavailable. After 1873, Beach’s demonstration subway line was no longer used.17 In 1912, when construction workers began building a subway line on Broadway, they rediscovered Beach’s tunnel, the original construction shield at the south end, and the remains of the wooden subway car. Unfortunately, the tunnel was destroyed during the new construction, and the original Beach Pneumatic Transit station, located in the basement of a nearby building, also disappeared when that building was torn down.18 However, not all was lost. Clearly, Alfred Ely Beach’s forward thinking inspired the transit of today, helping city-dwelling citizens of today and many more.

- Funk & Wagnalls New World Encylopedia, 2017, s.v. “New York City.” ↵

- Funk & Wagnalls New World Encylopedia, 2017, s.v. “New York City.” ↵

- Cricket, Vol 38 Issue 3, 2010, “New York’s First Air Train,” by Nathan S. Mayfield, 28-30. ↵

- St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture, 2nd ed., 2013, s.v. “Scientific American,” by Elizabeth D Schafer, 467-468. ↵

- St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture, 2nd ed., 2013, s.v. “Scientific American,” by Elizabeth D Schafer, 467-468. ↵

- Encyclopaedia Brittanica, 2018, s.v. “Alfred Ely Beach.” ↵

- Encyclopaedia Brittanica, 2018, s.v. “Alfred Ely Beach.” ↵

- Engines of Our Ingenuity, University of Houston, 1999, “No. 1474: Beach’s Secret Subway,” by John H. Lienhard. ↵

- Cricket, Vol 38 Issue 3, 2010, “New York’s First Air Train,” by Nathan S. Mayfield, 28-30. ↵

- Cricket, Vol 38 Issue 3, 2010, “New York’s First Air Train,” by Nathan S. Mayfield, 28-30. ↵

- Engines of Our Ingenuity, University of Houston, 1999, “No. 1474: Beach’s Secret Subway,” by John H. Lienhard. ↵

- Cobblestone, Vol 33 Issue 5, 2012, s.v. “The Secret Subway,” by Marcia Amidon Lusted, 12. ↵

- Engines of Our Ingenuity, University of Houston, 1999, “No. 1474: Beach’s Secret Subway,” by John H. Lienhard. ↵

- Cobblestone, Vol 33 Issue 5, 2012, s.v. “The Secret Subway,” by Marcia Amidon Lusted, 12. ↵

- Britannica Biographies, 2017, s.v. “Tweed, William Magear.” ↵

- Britannica Biographies, 2012, s.v. “Tweed, William Magear.” ↵

- Cobblestone, Vol 33 Issue 5, 2012, s.v. “The Secret Subway,” by Marcia Amidon Lusted, 12. ↵

- Cobblestone, Vol 33 Issue 5, 2012, s.v. “The Secret Subway,” by Marcia Amidon Lusted, 12. ↵

55 comments

William Rittenhouse

If I wouldn’t of read this, I would not know of how the subway system in New York came to be. I’ve used the subway system now and it is pretty efficient. It is pretty crazy to think how one corrupt guy almost stopped his invention from happening and we probably wouldn’t have developed subways until much later. I would say this is probably the best transportation invention of the 19th century which revolutionized the travel and public transportation.

kendrick Harrison

The article as a whole was magnificent–especially the exposition. I know very little about New York, so any bits of information about the culture, trade, or geography are helpful, and Iris managed to tie each of the categories together in a very convincing manner.

As for Alfred Beach, his story really resonates with me. Like him, I have a passion for inventing, so to see him take such a big risk (at his own expense) against a powerful and crooked man like Tweed, was inspiring to say the least.

Caden Floyd

Prior to reading this article, I had never knew where the ideas of an underground subway originated. However after reading the article, it has intrigued me how a secret tunnel built by a man completely changed public transportation for New York and it’s people forever. Starting off as a small project kept a secret, to completely revolutionizing the public transportation system for the generations to come. Although his model never was used to transport people in a subway, his idea helped shape the future of the underground transportation system.

Micaela Cruz

I had never heard of Alfred Ely Beach before reading this article, but after reading this article and learning about his contributions, it is surprising how little he is mentioned or credited with the creating of the underground transportation in New York. The author gave a great amount of detail to this story and even provided a bit more background on Beach than I would have expected. Overall, the quality content of this article was great.

Christopher Vasquez

It’s interesting to know where part of the inspiration for the subway comes from. Alfred Ely Beach’s forward thinking helped propel the scientific minds of inventors. Buying Scientific Americ American to help those who wanted to invent was a great idea; this way, those who could not readily access pertinent information found a great source of information. It’s also unfortunate that Beach ran into William “Boss” Tweed, a corrupt individual who would stop at nothing to make sure that his money and prospects were protected. In the end, however, despite being an obstacle, Beach was able to overcome him by funding an underground subway. Although it never became used as an actual subway system, his ingenuity was an impetus behind the underground subway.

Reagan Meuret

The subway system really was so innovative especially for its time. It is even more impressive on how it was created underneath an already extremely populated city. It is also very crazy to think it could have been created much sooner if it wasn’t for the crooked politicians of the time! Overall this article was a very good read over a very interesting man and innovation.

Adrian Cook

I have never been to New York to experience these subway systems in themselves but I know it’s a majority of the city’s transportation. Each day there’s thousands to millions who ride the subway train and it’s all thanks to the idea of Beach. If he didn’t do this operation secretly behind Tweed’s back then it would’ve taken many more years to develop a successful railway system. It was a smart invention because the surface of New York is filled with millions of cars.

Roman Olivera

Alfred Ely Beach, that’s a name I have not heard before. This seems like a man with vision for the future that was held back by greedy politicians. I guess not a lot has changed in 140 plus years. This man was truly the start of the New York subway system and his efforts seemed to be overshadowed by the actions of a corrupt local government in New York city. I learned a lot through this article a bout the early innovation of the Pneumatic Subway and the struggle for young inventors like Beach to be able to run with their ideas to help society as a whole. It was sad to hear that his system wasn’t allowed to be built during his lifetime and almost forgotten about until the building of the actual subway system was underway in 1912. This is a great article of information I definitely had never heard before. Thank you for shedding light on a little know but great inventor in american history.

Cooper Dubrule

I’ve always wanted to visit New York and after reading this article, even more so because its written really puts the population and atmosphere into perspective. I liked the story behind the subways and how Boss Tweed was involved in the situation as well. Now, the subway system in New York is the primary mode of transportation for many and it was nice to receive insight to the origins of them.

Harashang Gajjar

Elevated lines eventually gained popularity because of their lower cost. Thus the Interborough Rapid Transit Company didn’t begin underground public transit service until 34 years after Beach’s demonstration line first opened.Despite its appearance in Ghostbusters II, no elements of Beach’s subway remain. The station was lost to fire in 1898, and the tunnel was destroyed during construction of a Brooklyn-Manhattan Transit tunnel in 1912. Today’s City Hall station occupies the former tunnel’s footprint.