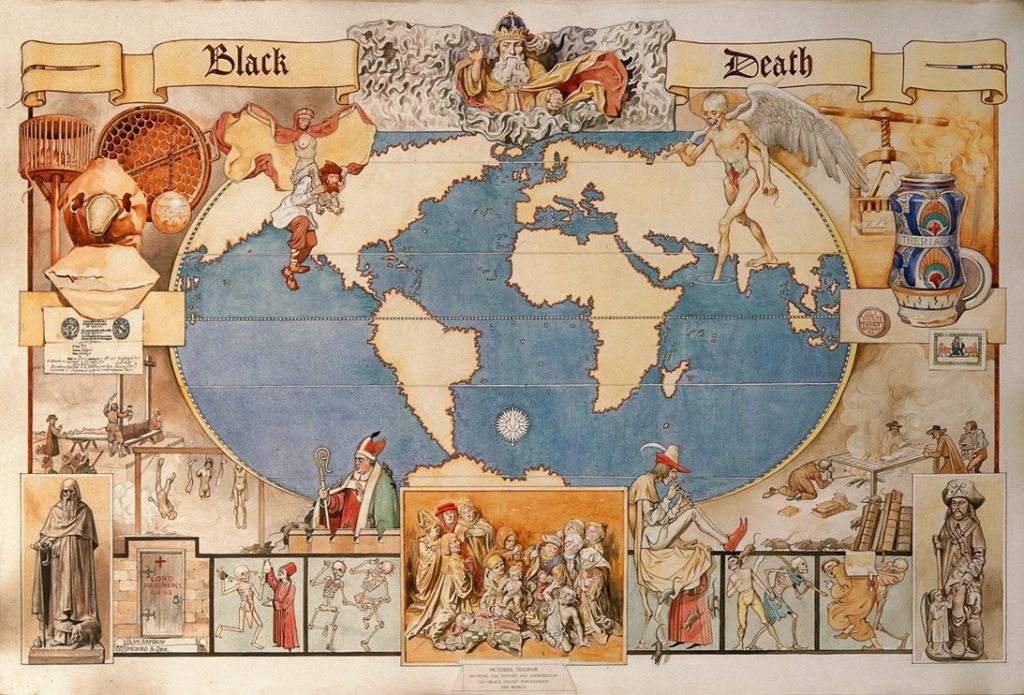

It’s 1346, and a killer is stalking European cities. Soon, bodies will be dropping dead, towns will be wiped out, infected rats will be taking over cities, and worldwide panic and insanity will settle in. Through much of its history, the Afro-Eurasian world had been struck with fatal pandemics before. Some epidemics would affect certain parts of the world, others would engulf the world in their deadly desires. The Bubonic Plague, also known as the Black Death, is arguably the most fatal pandemic the Eurasian world has ever witnessed. The people of Europe were not prepared to combat such a deadly disease, and would not be able to fight adequately against its unknown powers.

The Black Death spread through Europe like wildfire. It started during the winter of 1346, when a Mongolian army prepared to capture the town of Kaffa, located between the borders of Europe and Asia right on the edge of the Black Sea. Kaffa was known as one of Europe’s greatest trading centers, which would become an important catch for the Mongolian empire if captured. The Mongol army was infected by the Black Death, and they began rapidly dying on their expedition to the city of Kaffa. Thousands of Tartar Mongolians were dying daily, rapidly decreasing the Mongolian leader’s options on how they would capture the city of Kaffa. Regardless of any medical attention, once the disease was visible to its victim, it was an automatic death sentence. Though the Mongol leader had lost his troops to the Black Death, he was not going to waste the time or his troops on an attempt to storm the city. Instead, the Mongol leader took their giant catapults and launched their infected corpses over the walls and into the city of Kaffa. Once the corpses were in the town, people in the town of Kaffa started to die, and those that were still alive were desperate to survive this new sickness, and they began fleeing the town. People boarded ships and sailed southward into the Black Sea.1 Unfortunately, it was too late; their bodies had already been infected with the disease—and thus the spread of the Black Death in Europe began.

Those who fled Kaffa first brought the disease to Constantinople, and by 1347, the disease had reached the level of an epidemic. Constantinople was a prime trading hub for people all over Europe and Asia. Traders would come to Constantinople to sell their goods in the Byzantine city. Therefore, once the traders were done selling their goods and were ready to leave, their ships had already been infected by the disease that had hit Constantinople. But the traders left the city on their ships, unknowingly infected and carrying the disease even further into Europe. The ships leaving Constantinople contributed to the spread of the Black Death southward into the lands of the Mediterranean. The Black Death hit the port cities in Palestine, in Egypt, in Greece, in Italy, and also in North Africa.2

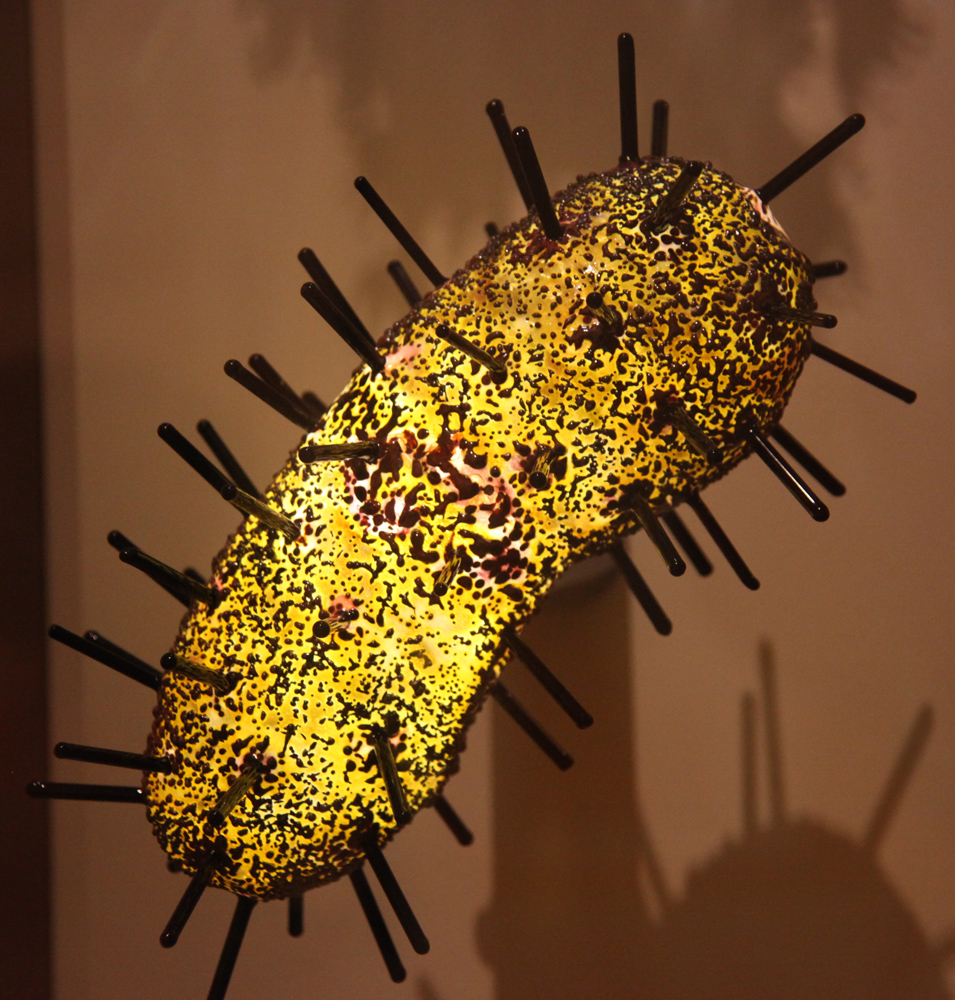

This Black Death was a disease unlike any other, one that was so unknown, that nobody knew how to handle it. Europeans were ill-prepared to combat what this disease would do to its victims. The Black Death spread through contact, much like most diseases. When it came to exposure to this bacteria—Yersinia pestis—it’s said that the easiest way for this disease to spread was through the skin. An open wound, a bug bite, a scratch, cracks in the skin was all it took for this bacteria to enter the body. It was carried by different parasites such as lice, fleas, ants, and other bugs, much of these found on rats and other vermin. The bacteria could be transmitted either from the parasite bite itself or even from the scratching of a bite, leaving an open wound for transmission. Once someone had become exposed, they would enter the incubation period. The average incubation period ranged from three to five days. Although that was the average, there were also cases where signs of the disease would show after 36 hours, while others wouldn’t show symptoms until fourteen days after exposure. This made it difficult to find a true minimum and maximum number of days for the incubation period.3 The symptoms of this virus were painful and deadly. After roughly three days after being exposed, a smooth yet painful lymph gland swelling known as a bubo would start to appear. These buboes were typically found in the groin area, armpits, and neck. In some cases, victims of the Black Death could potentially feel pain in those areas even before the bubo had become visible. Other symptoms included but were not limited to high fevers, muscle aches, vomiting, seizures, prostration (or weakness), chills, and headaches. Needless to say, it was a very excruciating way to die.4 The Black Death not only had effects on one’s body, but also affected Europeans socially. Since it was such a fatal disease, mass hysteria kicked in and everyone was living in terror. People began to disregard the rules because they saw no point in following them anymore if they were going to die. Brothers began abandoning their brothers, parents started to neglect their children, and everyone was made to fend for their own.5

Now that the Plague stalking Europe had spread through its ports, it began to spread even more. By 1348, the plague reached the French city of Avignon. At the time, the city of Avignon was the headquarters of the Catholic Church and of Pope Clement VI. The plague hitting the French city of Avignon would start to affect religious affiliations. Because of how deadly this plague proved to be, priests began fleeing their town in the hope of escaping this killer. Unfortunately, this caused people to start questioning priests and their loyalty to their religious work. It was then that even religion began getting affected by the Black Plague.6 This plague truly put some religions to the test.

Europeans were looking for someone to blame, and unfortunately, their fingers pointed to the Jews. Jews were accused of poisoning wells, foods, and streams. Because everyone was living in hysteria, many people believed that Jews were to blame for the deaths, and they began torturing Jews to death, often by burning them to death.7 People felt that Jews should suffer and die in a way that would be painful, yet also cleansing of the plague, which explains why burning became a way of torture. Not only did the Black Plague affect the Jews, but it also began to affect Christians, who would start forming ideas for why this plague began in the first place. Many believed that the plague was the righteous judgment of God because of how sinful humanity was. While it was very seldom, there were still people that had hope that through prayers and processions, God’s vengeance of the plague could be resolved. The plague also began causing problems for the Church. There were fewer and fewer priests who were able and willing to hold parish services, so this made it difficult to keep the religious services running.8

Many cities that had become infected with the plague were living with the dead piling up. The corpses of those who lost their lives to the plague were lying around creating piles of the dead, practically taking over the city. The problem with this was that the corpses needed to be removed and buried, but because of how infectious this plague seemed to be, nobody wanted to do the tasks of touching any of the corpses. This meant that this dirty work was mainly reserved for low-class thugs and criminals. Not only were societies struggling to figure out who was going to bury the bodies, but they also struggled with where the bodies were going to be buried. European Christians expected to be properly buried, preferably on the sacred ground by a church. But because of how many people were dying and how fast they were dying, burial options became slim to none. The Renaissance writer Giovanni Boccaccio wrote,

“There was not enough concentrated (sacred) ground to bury the great multitude of corpses arriving at every church every day and almost every hour… So, when all the graves were occupied, very deep pits were dug in the churchyard, into which the new arrivals were put in the hundred. As they were stowed there, one on top of another, like merchandise in the hold of a ship, each layer was covered with a little earth, until the pit was full.”9

Due to the lack of space for graves and the belief that fire would cleanse infection, some communities turned to cremation of the bodies, which wasn’t a typical way of burial at the time. Needless to say, the Black Death affected people physically, mentally, and spiritually.

France had been completely overrun by the Black Death, and it wound up reaching the banks of the English Channel. There was hope that the infection would stop there, due to the massive waterway separating England from the continent. Unfortunately, this was not the case. As mentioned before, not only could people spread the disease, but rats and other vermin could too. So, from one rat-infested town to another, the rats made their way onto trading vessels headed to the lands of England, Germany, Poland, and Russia, which wound up devasting Moscow by 1352. This stalker of death was on a killing rampage that seemed impossible to stop, no matter what attempts were being made.10

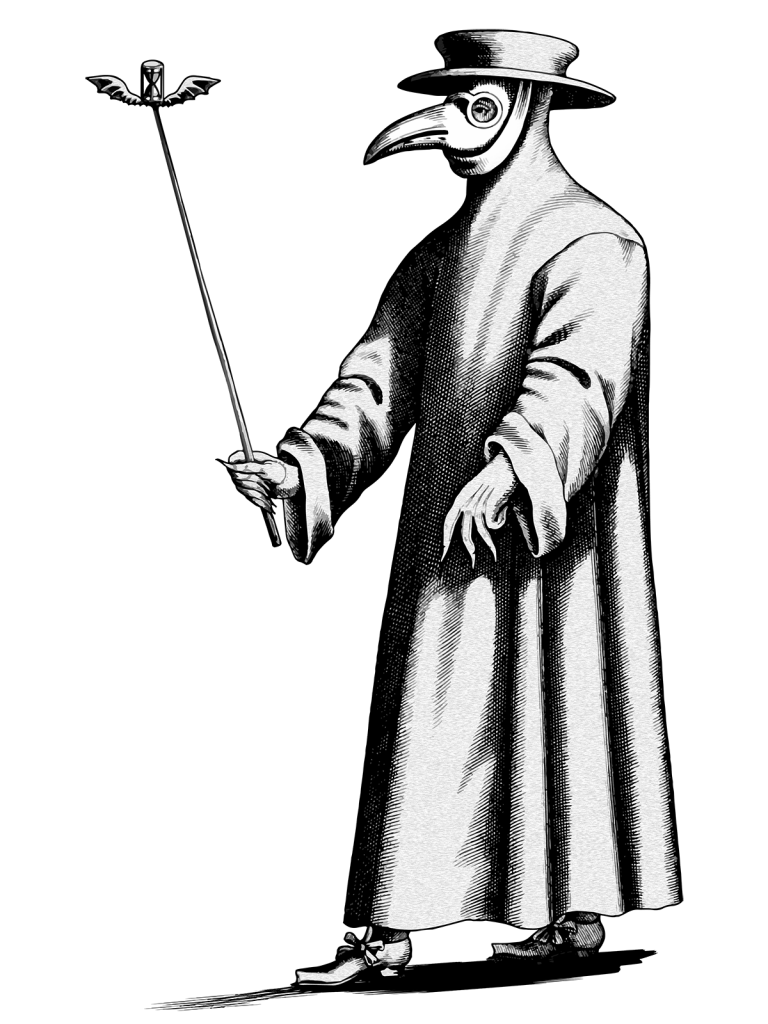

How did Europeans attempt to stop the plague from spreading? Many of us have seen the sinister costume that was worn during this time, but don’t know the reasonings behind it. The costume would be known as Doctor of the Plague. It consisted of a beaked white mask, a black hat, and a waxed gown.11 A royal physician, Charles de L’Orme, described the costumes as such:

“The nose is half a foot long, shaped like a beak, filled with perfume with only two holes, one on each side near the nostrils, but that can suffice to breathe and carry along with the air breathes the impression of the herbs enclosed further along in the beak. Under the waxed coat, we wear boots made in Moroccan leather from the front of the breech’s smooth skin, the bottom of which is tucked into the breeches. The hat and gloves are also made of the same skin…with spectacles over the eyes.”12

At the time, it was thought that different herbs and perfumes could cleanse and/or purify the air, which is why the beak of the mask was filled with up to sixty ingredients. Some of these ingredients included honey, cinnamon, agarics, ground mummia, opium, and desiccated viper. The goggles were used to help apply leeches to the buboes to try to suck out the infection. Finally, the wooden cane was used to help remove patients’ clothes, record their pulse, and keep themselves at a safe distance.13 Regardless of doctors’ best efforts, essentially nothing stopped people from dying of this disease, and many of the doctors fled during the plague hoping to save themselves.14 Through a lot of trial and error, even with most doctors’ best interests at heart, very few would find a way to combat the disease. One of the most famous doctors in Italy at the time, Gentile da Foligno, wrote about what he thought was a defense against the Black Plague. For one, people should be very aware of what they are consuming in terms of food. Fish should be avoided, as well as lettuce if it had been left out in the cold. It seemed imperative to eat good meat such as chicken, gelded cows, and lactating goats. Second, people should take prescription medicine that would help purge and cleanse the body. Third, roughly two or three times a week, people were recommended to indulge in theriac—a paste made as an antidote to poison. Finally, it was highly stressed that people create large fires within their homes in an attempt to keep the infected vermin away.15 Many doctors would do all that they could to try and put the Black Death to an end.

Regardless of everyone’s best efforts to stop that plague, it would not end with a happy ending. The Black Death wound up killing between 100-200 million people, which was roughly 60% of the population of Europe at the time.16 While the first wave of the plague would come to an end in 1351, the nightmare of the second plague returned in 1361 and would, unfortunately, bring a cycle of terror to Europe once again.17

Throughout this writing process, there are many individuals to whom I’ve come to owe the utmost respect and gratitude. First, I would like to thank Jose Chaman for his guidance in helping me choose my topic and prepare my project proposal. Second, I would like to thank my colleagues at The Learning Center, who continuously encouraged me while writing my article. Third, I owe the utmost gratitude to Dr. Whitener for giving me this opportunity to display my work publicly and for providing me with much-needed revisions that have helped strengthen my writing skills. Finally, I’d like to thank my parents for providing me with a great support system and the confidence I needed to complete my writing.

- Emily Mahoney, The Black Death: Bubonic Plague Attacks Europe (New York, NY : Greenhaven Publishing LLC, 2016), 17. ↵

- Emily Mahoney, The Black Death: Bubonic Plague Attacks Europe (New York, NY : Greenhaven Publishing LLC, 2016), 18-19. ↵

- James Cantlie, “The Signs and Symptoms of Bubonic, Pneumonic, and Septicæmic Plague,” Br Med J 2, no. 2078 (October 27, 1900): 1229–32. ↵

- Stephanie Eckenrode, “Bubonic Plague,” Salem Press Encyclopedia of Health, 2021. ↵

- Emily Mahoney, The Black Death: Bubonic Plague Attacks Europe (New York, NY : Greenhaven Publishing LLC, 2016), 71-72. ↵

- Emily Mahoney, The Black Death: Bubonic Plague Attacks Europe (New York, NY : Greenhaven Publishing LLC, 2016) 25-26. ↵

- S. K. Cohn, “The Black Death and the Burning of Jews,” Past & Present 196, no. 1 (August 1, 2007): 4. ↵

- John Aberth, The Black Death: The Great Mortality of 1348-1350, Second, The Bedford Series in History and Culture (Bedford Books, 2005), 79. ↵

- Emily Mahoney, The Black Death: Bubonic Plague Attacks Europe (New York, NY : Greenhaven Publishing LLC, 2016), 22. ↵

- Emily Mahoney, The Black Death: Bubonic Plague Attacks Europe (New York, NY : Greenhaven Publishing LLC, 2016), 24. ↵

- Christian J. Mussap, “The Plague Doctor of Venice,” Internal Medicine Journal 49, no. 5 (2019), 1. ↵

- Christian J. Mussap, “The Plague Doctor of Venice,” Internal Medicine Journal 49, no. 5 (2019), 2-3. ↵

- Christian J. Mussap, “The Plague Doctor of Venice,” Internal Medicine Journal 49, no. 5 (2019), 3. ↵

- Emily Mahoney, The Black Death: Bubonic Plague Attacks Europe (New York, NY : Greenhaven Publishing LLC, 2016), 33. ↵

- John Aberth, The Black Death: The Great Mortality of 1348-1350, Second, The Bedford Series in History and Culture (Bedford Books, 2005), 49-51. ↵

- Christian J. Mussap, “The Plague Doctor of Venice,” Internal Medicine Journal 49, no. 5 (2019), 2. ↵

- Emily Mahoney, The Black Death: Bubonic Plague Attacks Europe (New York, NY : Greenhaven Publishing LLC, 2016), 86-87. ↵

62 comments

Shecid Sanchez

I want to start off by saying congratulations on writing such an amazing article! The Black Death went down as such a historic event and we will continue to learn about it for generations. I learned the general idea about the Black Death in school but I never learned how it began to spread through Europe. I was stunned to say the least when I found out that they catapulted the infected bodies into Kaffa. I also found it crazy that they blamed the jews and began to torcher them because they wanted revenge. The Europeans wanted the Jews to suffer as much as they did so they would burn them alive.

Mateo Ortega-Rios

This article was very intriguing, from the start it was perfectly structured and took my attention. I greatly enjoyed the topic, I got to learn more about the “Black Death”. From the title to the very end of the article it was very entertaining. There was also much detail added to a very historic event that occurred.

Ana Barrientos

Congratulations on your nomination, I really enjoyed reading your article. It was informative and well written, I also liked the images you provided. I especially liked the image of the map and how it showed where the bubonic plague spread. It was interesting to read that so many people started to abandon their own family and have that mindset of “every man for themselves”. It really showed how intense and scary it was for these people. Overall, great job!

Jose Ignacio Guerrero Donoso

I love how you added such great detail to a historic moment in the world, that affected a lot of people in Europe.

Dylan Vargas

This is an interesting topic and a major topic in the history of the world, The black death was a serious disease in the 1300s and I am glad that the article gave us a story to work with. How Kaffa to Constantinople and the plague doctors that wore those types of clothes. It’s all very interesting to me and other people, I can see why it was nominated.

Madeline Bloom

I like this article very much. You did a great job with the amount of detail to create a great picture in my mind while reading it. I am guessing that it was harder to prevent a pandemic back during this time period like it is now, because of all the resources we have now. We did not have the PPE to protect people and doctors from getting the virus and creating more of a problem.

Francisco Caballero

This was a great article, I really enjoyed the intro and how it set up the rest of the article. It was compelling and draws the reader into the rest of the story. I like the transition and how you covered the history of the bubonic plague.

Sudura Zakir

Amazing article about the European historical black death with plenty of information. The article highlights many events that happened during the plague and depicts the scenarios broadly. I enjoyed reading the whole context and it made me more curious about learning about what happened next. The style of storytelling was entertaining and visual. The title was attention-seeking and made me more interested in the serial killer.

Vanessa Preciado

This article was very good! I never knew too much about the plague until reading this article. It’s really messed up how something like this actually happened. And the technique they used to fire back (missling the infected bodies to their enemies) was a really bright idea but very horrible in every way. Another thing that stood out to me was the the plague doctor outfit and mask. This outfit was designed specifically for this time, and now we know how its used. Great job!

Veronica R

Such a well written and informative article. Referencing the Bubonic Plague as a serial killer on the loose in the introduction really grabbed by attention and encouraged me to keep reading. It was a different take on what started as a medical crisis, but definitely became a serial killer with the decision of the Mongol leader to so callously catapult the infected corpses over into the city of Kaffa, thus employing biological warfare to achieve his desired result. The savageness of how the sick and departed were treated was so disheartening, but is an honest look at the history of this plague. I learned quite a bit from this article, for instance, I never knew that the Bubonic Plague wiped out 60% of the European population or how the lack of proper burial space caused for stacking of the bodies with just a little bit of dirt in between. Again, so disheartening, but honest. The mass hysteria, physical, mental and spiritual effects referenced in the article make sense when they were up against a plague that, if caught, meant an automatic death sentence. The analysis of these feelings of panic and doubt, by the author, brought back the humanity to a plague that caused so much of the population to disregard human decency. The author did a great job balancing historical medical facts, with grim details and human reactions helping to keep me invested in this article to the very end.