As John Brown sat by a fire in the fall of 1859, he recollected the violent scenes he endured in Kansas three years earlier. He remembered the harassment, threats, and insults that were plundered by gangs of marauding ruffians from Missouri.1 He remembered the one black night when Brown and his four sons seized and killed five of the worst of the border ruffians who were harrying the free state settlers.2 He remembered the killing of his own son, Frederick, who died at the hands of pro-slavery settlers. As the fire continued to burn, he remembered the only time he ever saw his father kneel in prayer: when his father first vowed himself and them to attack slavery by force.3 The decision was solidified within him: only bloodshed could wash away the sin of slavery. He had reached a personal turning point, viewing himself as an instrument in the hands of an angry God.4

Brown’s war on slavery was not always this radical. Brown’s letters from youth and adulthood before 1855 betrayed no plans to attack slavery by force of arms. Brown grew up in a deeply religious household, having been raised with strict Calvinist and Puritan traditions. Accounts describing John Brown’s deep religious convictions and upbringing state that he became a “firm believer in the divine authenticity of the Bible.” He read and reread it, committing long passages to memory. He wove it into the very essence of his being—its history, poetry, philosophy, and truth—until it molded his soul.5 In the early makings of Brown, one incident stood out as a precedent of his passion for abolition. During the War of 1812, a landlord welcomed Brown to his home. Brown found praise and good food in the landlord’s parlor, but what he found even more interesting was another boy in the landlord’s yard. The boy’s diffidence warmed to the kindly welcome of the stranger, especially because he was black, half-naked, and wretched. In John’s very ears, the kind voices of the master turned into harsh abuse to the boy. At night, Brown witnessed the slave lay in the bitter cold. He watched as they beat the boy with an iron shovel, again and again and struck him with any chance they got. With wide-eyed silence, John questioned why this was happening. The boy was intelligent; he was kind, and John acknowledged him as “fully if not more than his equal.” He asked himself, “Is God their Father?” As he was in deep reflection of what he had witnessed, his hatred for slavery began to fester within him.6

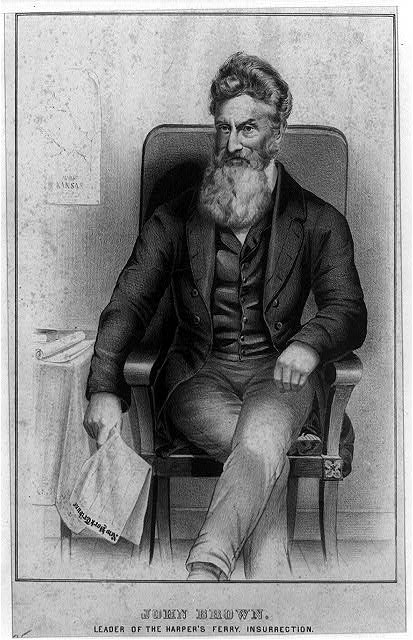

By 1855, Brown stood at five feet ten inches tall and 150 pounds. He was an aging, leathery, “rustic-looking” “gentleman” who had never fired a gun in anger or had seen a man murdered.7 However, it was the events that occurred in Kansas that transformed him. Brown’s five sons had originally moved to the newly opened Kansas territory, leaving draught-plagued Ohio in 1854, and Brown followed a year later. In 1854, the Kansas-Nebraska Act had just been passed, which opened the Nebraska territory to land-hungry settlers despite the presence of Indians who occupied a large area of the land. Then, without warning, Illinois Senator Stephen A. Douglas agreed to rewrite the bill to divide Nebraska into two territories on the 40th parallel; and even worse, he agreed to a provision that repealed the provision in the Missouri Compromise of 1820 that stated that slavery was prohibited in all future territories outside of the Louisiana Purchase north of 36°30′ line. Kansas quickly became a “potential prize” in an eruption of long-simmering sectional rivalries, as by March 1855, around 5,000 armed Border Ruffians from Missouri came into Kansas to vote. As tensions escalated, isolated incidents of violence arose. Injustice in the government became clear with the failure of the territorial government to prosecute pro-slavery crimes. It created a sense of fear among the free-state settlements. Finally, on the night of May 24, 1856, in response to the sacking done by pro-slavery settlers to an anti-slavery stronghold in Lawrence, Kansas, Brown and his party of six men descended on the cabins of his enemies. When there, they killed five pro-slavery settlers with short, heavy, calvary broadsword. His men then “confiscated” their horses and left. What was deemed as a “retaliatory blow” against the proslavery party became known as the Pottawatomie Creek Massacre, and it was the turning moment in which Brown understood that armed resistance could be the answer to successfully combating the institution of slavery.8 Although believing the action was justified, pro-slavery settlers did not take this incident lying down. A large pro-slavery force burned down the town on August 30 in retaliation for the killings, causing Brown’s men to be caught in a firefight in which Frederick, Brown’s beloved son, was shot and killed. This incident fully ignited the fire within Brown.9 He now had a mission that this personal loss had incited: only violence was an acceptable means to put an end to slavery. Now, he had plans for something bigger—something that would show how much he was willing to sacrifice for this cause.

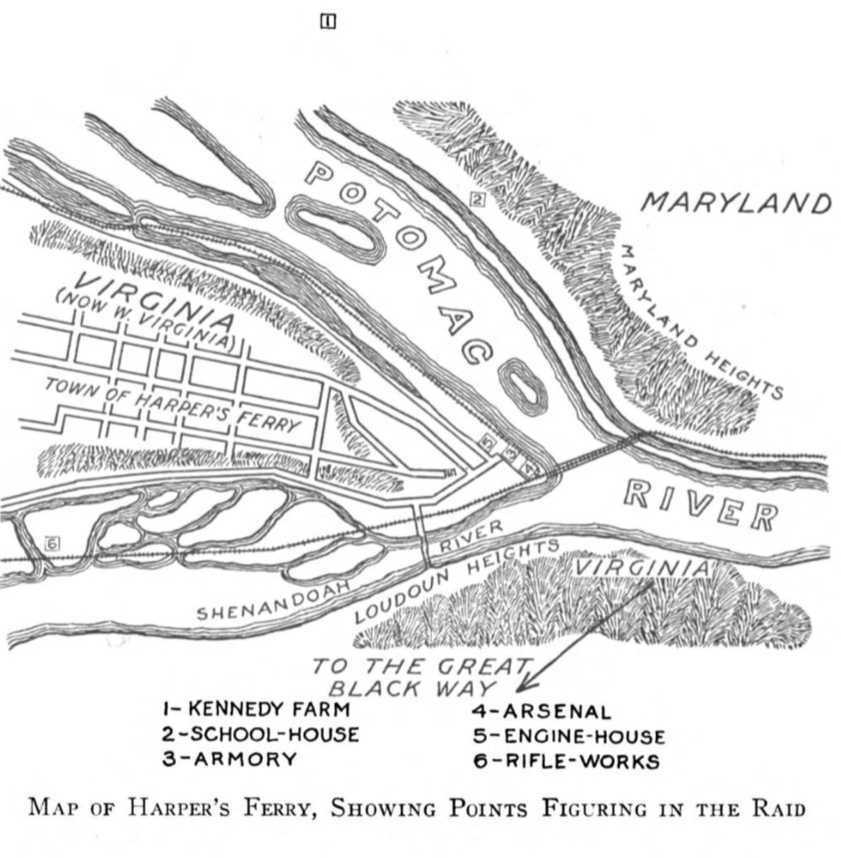

In his mind, there was a mature plan growing for an attack on slavery in the United States in a way that would shake the very foundation of the institution. At first, he proposed a black school in Hudson, where he would educate the students there and let them become transformed with revolutionary ideas. Then, this idea progressed into possibly settling in a border state educating slaves openly, and sending them out as emissaries. Then, finally, in the spring of 1859, his eyes were fixed on Harpers Ferry.10 He began studying the Southern geography, noting the rivers, swamps, and mountains. The plan soon presented itself clearly as John Henry Kagi, one of Brown’s followers described, “The mountains of Virginia were named as the place of refuge, and as a country admirably adapted in which to carry on guerrilla warfare. In the course of conversation, Harper’s Ferry was mentioned as a point to be seized, but not held,- on account of the arsenal.”11 This plan was set: They would raid the federal armory at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, and, with the arms captured there, begin a slave revolt throughout the South. However, with this glorious plan, Brown needed some monetary assistance. To help with this, a band of men from Massachusetts and New York became known as the Secret Six. This group consisted of: Thomas Higginson, Dr. Samuel Howe, Theodore Parker, Franklin Sanborn, Gerrit Smith, and George Stearns. Sanborn was at Gerrit Smith’s home in Peterboro, New York on February 22, 1858, when John Brown first revealed that he was planning this direct attack. On the following day, Sanborn later related, “Mr. Smith restated in his eloquent way the daring propositions of Brown, whose import he understood fully, and then said in substance, ‘You see how it is; our dear old friend has made up his mind to this course, and cannot be turned from it. We cannot give him up to die alone; we must support him. I will raise so many hundred dollars for him; you must lay the case before your friends in Massachusetts and ask them to do as much. I see no other way’.”12 Although conflicted in skepticism of his plan, they still showed their support. However, Brown encountered even more skepticism in the case of Frederick Douglass. After the violence in Kansas, Brown met Douglass in August 1859, at an abandoned stone quarry near Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, and told him of his plan to draw southern slaves off into the Allegheny Mountains. Still attached to principles of nonresistance, Douglass recalled that he had tried to convince Brown of the illogical nature of this, and instead told him that effort should be concentrated on converting the slaveholder to the cause of abolition.13 Although Brown did have a lasting impression on Douglass, he was still unsuccessful at winning Douglass’s heart and mind in fully supporting his plan of direct attack on the South. On top of this, Brown’s positionality produced some backlash. For example, some white U.S. Americans rejected Brown as a heroic figure because “he was too close to blacks.” Even white abolitionists in the North showed disdain for the idea of arming Black people, especially if they were former slaves.14 This opposition soon led to feelings of isolation and doubt in Brown, as figures like Douglass, ones that he looked up to, were not able to see the need for violent confrontation. These emotions, however, soon turned into heavy frustration. According to W.E.B Du Bois, “Brown’s intimacy with Black people and their pain gave Brown’s cause credibility and direction because he wasn’t speaking for Black people, but with them, as he participated in and took direction from the Black abolitionist network, assisted with the Underground Railroad, and lived and worked in solidarity with Black people.”14 He was reminded of the purpose of this mission that was set before him, and he was ready to fully prepare for the raid.

With this glorious plan, he needed to be bold and detailed in his planning–and he did so by making public appeals for assistance, speaking and meeting with reformers and “capitalists” as he traveled about the East in the spring of 1857. On March 4, he placed an appeal for funds in Greeley’s Tribune and other papers. He stated, “I ask all honest lovers of Liberty and Human Rights, both male and female, to hold up my hands by contributions… either as counties, cities, towns, villages, societies, churches, or individuals.” On April 1, he sought support from former territorial Governor Andrew H. Reeder, who had been driven out of the territory of Kansas for allying himself with free-state fraction, stating, “I take the liberty of sending you the enclosed appeal & hoping that you may find it in your way to afford me some aid in securing the means of an outfit [a wagon and team].”16 However, neither he nor the men underneath him received any sort of pay. In Massachusetts two weeks later, Brown wrote to Eli Thayer, founder of the New England Emigrant Aid Society and the man who was solely responsible for sending anti-slavery families to Kansas. Brown had asked for help in getting a small arms shipment to Ohio and in purchasing “two sample Navy-sized Revolvers” of the sort he wanted to purchase in large quantity. In order to impress him with the urgency of the matter, he also wrote, “I am advised that One of the U.S. Hounds is on my track” and “I have kept myself hid for a few days to let my track get cold. I have no idea of being taken.” He boasted, “I intend (if God’s will) to go back with Irons in rather than upon my hands.”17 Unfortunately for Brown, the contributions from his efforts had been disappointing. In early March, he had “vented” his frustrations in a short piece that he titled, “Old Browns, Farewell to the Plymouth Rocks; Bunker Hill Monuments; Charter Oaks, & Uncle Tom’s Cabins.” To his surprise, the immediate response to this piece was a plethora of gifts from wealthy New Englanders. George Luther Stearns, who would soon become a Secret Six member, pledged $7,000 and provided most of the money and weapons for Brown’s soon-to-be war on slavery. Brown was finally seeing some success in his contributions, and he had raised $13,000, which soon after reached $30,000. The following day, he asked Eli Thayer to “Have Allen & Co send me by Express” the large revolvers he had requested “as soon as may be; together with his best cash terms… by the Hundred.”18 He also personally ordered rifles and pistols he had already purchased from Allen & Co. packed in a strong suitable box and sent to Cleveland. The “piece” that had gained the support of New Englanders soon became known as one of Brown’s most successful pieces of propaganda, as it pulled at the heartstrings of many by building a sense of guilt in men too comfortable in their material lives to be at ease with their consciences in a slaveholding nation.19 Success in fostering aid and support, however, was short-lived, as it became harder to operate unnoticed. With increasing tensions also came increasing violence in the South. The urgency of Brown’s message resonated with his followers, even as doubts persisted about whether they could truly succeed. By this time it was October of 1859, and Brown could not waste any more time.

October 16, 1849. Eight o’clock. Sunday evening. The night that had been awaited for three years. Finally, all of the anger that had intensified and consumed Brown and his twenty-one men had led up to this single day: the day when Brown was able to say, “Men, get on your arms; we will proceed to the Ferry.”20 The forces that made his attack consisted of seventeen white men and five colored men, though it is said that those who had escaped during the raid assisted outside by cutting telephone wires and tearing up railroad tracks. First, once they arrived at the Ferry, they rapidly extinguished the lights of the town. Then, they took possession of the Armory building, which was guarded by three watchmen. Without meeting resistance or alarm, they seized and locked up in the guard-house.21 At around ten thirty, the watchman at the Potomac Bridge was seized and secured, and when the next watchman arrived at midnight, he ran after Brown’s men shot at him. Approximately a quarter past one, the western train arrived, only to find the bridge guarded by armed men. When the conductor and other passengers attempted to cross, they were forced to retreat at gunpoint. Tragically, a black man was shot and died the following morning. The passengers of the train sought refuge in a nearby hotel for several hours while the conductor, though eventually allowed to cross at three in the morning, refused to proceed immediately. Shortly after midnight, six of Brown’s men, under the command of Captain Stevens, took over the residence of Colonel Lewis Washington, who was a local plantation owner. They succeeded in capturing Washington, confiscating his arms, and freeing his enslaved people. Next, the group under Stevens raided the residence and captured Mr. Alstadtt, a local slaveholder, and his son while also liberating their slaves. It was decided that the newly freed, along with every male citizen who appeared in the street were confined in the Armory until they numbered between forty to fifty.22 Brown then informed his prisoners that they could be released on the condition of writing to their friends to bring a slave as ransom. At daybreak on Monday, October 17, Brown walked across the bridge with the train’s conductor. Whenever anyone asked the object of their captors, the uniform answer was “To free the slaves;” and when one of the workmen, seeing an armed guard at the Arsenal gate, asked by what authority they had taken possession of public property, he was answered, “By the authority of God almighty!” The delayed train was then allowed to proceed eastward from Harpers Ferry, by Brown’s permission, leaving the place completely in the military possession of the insurrectionists run by Brown. And it was deemed successful at that moment: they held, without dispute, the Arsenal, with its offices, workshops, and grounds. Their sentinels were on guard at the bridges and principal corners, and were seen walking up and down the streets. Every man who ignorantly approached the Armory was immediately seized; by eight o’clock, the number of prisoners was over sixty.23 Brown grew confident in his and his men’s control as he watched them seize more prisoners and land. For a brief moment, victory seemed within reach.

However, soon enough, this conflict quickly began to be no longer so one-sided. The white Virginians, who had arms, started preparing to use them. Soon after daybreak on the 17th, local Virginians began to fire at Brown’s guards. In one instance, as the guards were bringing two men to a halt, a man named Turner fired on them. Shortly after, a grocer named Boerly began to shoot but was instantly killed by return fire. Incidentally, Brown’s son, Watson, was mortally wounded by the resistance encountered.24 As word continued to spread of what was happening, half an hour after noon, a militia force, four hundred strong arrived from Charleston and were rapidly disposed so as to command every available exit from the place. They were able to close down onto the Shenandoah bridge that had been captured by Brown and his men. In doing this, they killed one of Brown’s men and captured William Thompson, a neighbor of Brown, unwounded. The rifleworks were attacked next, being defended by only five of Brown’s men. They attempted to cross the river and four were able to reach a rock in the middle of it, before having to face around four hundred Virginians who were lined on either bank of the river until two of them were dead, and the third mortally wounded when the fourth finally surrendered. Kagi, who was Brown’s Secretary of War, was one of the killed. William H. Leeman, one of Brown’s captains jumped into the river and threw up his arms in surrender crying “Don’t shoot!” However, a Virginian, enraged, fired his pistol and shot the captain dead.25

By this time, all the houses around the Armory building were taken back and held by Virginians. Captain Turner, who was the individual who fired the first shot in the morning, was killed by one of Brown’s men at the Arsenal gate. Dangerfield Newby, a Virginia slave, and Jim, one of Colonel Washington’s slaves, with a free slave who had lived on the estate, were shot dead. Then, being hit with a bullet, Oliver Brown, the old man’s beloved son, came inside the gate of the Armory, lay quietly down without a word just as his brother Watson had done, and a few moments after, passed. Thompson, Brown’s neighbor who had been captured earlier, was kept in a parlor where he was confined, but soon after was dragged out to the bridge by an angry mob and shot in cold blood. By five in the afternoon, more militia were pouring in, telegraph and railroads repaired, and reinforcement from Washington and Richmond. Brown and his few remaining men retreated to the engine house, where they were surrounded by 1,500 armed Virginians.26

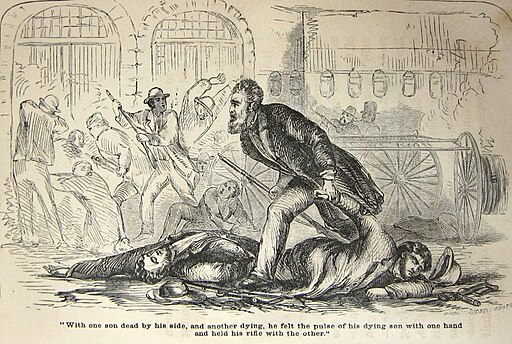

Despite these overwhelming odds, Brown continued to resist and refused to surrender. When the firing ceased at nightfall, Brown offered to liberate his prisoners on condition that his men be allowed to cross the bridge in safety, but it was rejected. By now, Brown’s forces were reduced to four unwounded beside himself, with around half a dozen slaves from the Ferry. These half dozen, were unable, even if willing, to rejoin their chief in the fight. They attempted to flee during the night to Maryland and Pennsylvania, but two of them were captured. During the night, Colonel Lee, with ninety United States Marines and two pieces of artillery, arrived and took possession of the Armory. Brown remained awake and alert through the night, managing to remain perfectly cool and calm despite the chaos. Colonel Washington states, “Brown was the coolest man he ever saw in defying death and danger. With one son dead by his side and another shot through, he felt the pulse of his dying son with one hand held his rifle with the other, and commanded his men with utmost composure, encouraging them to be firm and to sell their lives as dearly as possible.”27

At seven in the morning on October 18, the Marines advanced to the assault, broke in the door of the engine house by using a ladder as a battering ram, and rushed the building. One of the defenders was shot and two marines wounded, but the odds were too great. In an instant, all resistance was over. Brown was struck in the face and knocked down, after which the blow was several times repeated, while a soldier ran a bayonet twice into his body. All the insurgents would have been killed on the spot, had the Virginians been able to distinguish them with certainty from their prisoners. All of Virginia, including the Governor rushed to Harper’s Ferry once they learned it was all over and that the insurrection was completely suppressed. The survivors were subjected to an alternation of queries, which they met bravely as they confronted the bullets of their numerous and rapidly increasing foes. They answered frankly and none of them sought to conceal the fact that they had struck for Universal Freedom at all hazards. C.L Vallandigham, of Ohio, visited Brown and on his return home, he said: “It is vain to underrate either the man or the conspiracy. Capt. John Brown is as brave and resolute a man as ever headed an insurrection. He has coolness, daring, persistence, stoic faith and patience, and a firmness of will and purpose unconquerable. He is the farthest possible removed from the ordinary ruffian, fanatic, or madman. Certainly, it was one of the best-planned and best-executed conspiracies that ever failed.”28

Brown and his four men, Stevens, Coppoc, Copeland, and Green, were placed in the old jail at Charleston, eight miles from Harper’s ferry, about five o’clock in the afternoon on the day of their capture.29 In the days after the raid, Brown attempted to press these men into service on his behalf. They would “testify that they heard me continually order my men not to fire into houses, not even when we were fired upon from them, lest we should kill innocent persons… Your own citizens,” he replied hotly to a skeptical reporter, “will testify that such were my orders; that is the fact and you know it.” Brown would call upon the prisoners to give evidence of his innocence at his trial. He wanted to stand trial “that he might have justice as to the faith of [his and his men’s] motives.”30 When he failed as a guerilla leader and insurrectionist, he grasped that he might still win a propaganda victory over slavery as a man moved solely by compassion for the “downtrodden.” Facing certain execution, he determined to bear further witness on behalf of “God and humanity.” If God had permitted John Brown to fail as a soldier, He had miraculously permitted him to live to stand trial and given him an unequaled pulpit from which to offer that final testimony. Just a week after the raid, he and the other prisoners were indicted and ordered to trial. Brown asked that his life not be spared; he insisted instead that he was “ready for his fate.” But he demanded to be “excused” from a “mockery of a trial” and from being “foolishly insulted only as cowardly barbarians insult those who fall into their power.” Given a “fair trial,” he declared, he would present “mitigating circumstances… in our favor.”31 Throughout the trial, Brown felt “no consciousness of guilt,” he said, adding “I never had any design against the liberty of any person, nor any disposition to commit treason or commit any person to rebel or make any general insurrection. I never encouraged any man to do so, but always discouraged any idea of that kind.”32

Brown’s speech won widespread approval in the North and the admiration of subsequent generations of idealists and reformers beguiled by his courage, “manliness,” and high-mindedness. By accepting his sentence– “I say let it be done”–Brown inspired the abolitionist conviction that he “gave his life” for the slave. Even if his raid was ill-conceived, admirers said, Brown had sacrificed even his own sons in the cause of “God’s despised poor.”33 In the courtroom two weeks later, Brown hoped to speak past his immediate listeners to sympathetic northerners. In citing the Golden Rule, trying to do for others (the enslaved people) what he would want done for himself if he were in their position, and embracing his fate on behalf of God’s “despised poor,” he used effort to picture himself as the protector of his hostages and as the victim of needless violence. This won vast sympathy in the North if not from his jury. Ralph Waldo Emerson famously announced that Brown’s martyrdom would make “the gallows glorious like the cross.” Even cautious Republicans like Lincoln, who believed Brown “insane” and disapproved sternly of his attack, nevertheless conceded Brown’s “great courage and [rare] unselfishness.” William Lloyd Garrison, the voice of nonresistant abolitionism, concluded that Brown “had no other motive for his conduct at Harper’s Ferry, except to break the chains of the oppressed, by shedding of the least possible amount of human blood…, and… if he shall be put to death, he will not die ignobly, but as a martyr to his sympathy for a suffering race, and in defense of the sacred and inalienable rights of man.”34 John Brown’s conduct throughout the trial, even while still weak from his wounds, won the admiration of both supporters and enemies alike. His calm attitude, unmoveable conviction, and willingness to die for the abolitionist cause made him a martyr for many in the North, while the South continued to see him as a grave threat to the entire institution.

His verdict was delivered on November 2, 1859, just a few weeks after he raided Harpers Ferry. He was sentenced to death, and the execution was scheduled for December 2, 1859. The day of his execution dawned gloriously; twenty-four hours before he had kissed his wife goodbye, and on this morning he visited his doomed companions, Shields Green and Copeland first; then Cook, Coppoc, and Stevens. At last, he turned toward the place of his hanging. Brown rode out into the morning. “This is a beautiful land,” he said. Wide, glistening, rolling fields flickered in the sunlight. Some said he kissed a black child as he passed. As he hung there knelt the funeral guard he prayed for when he said, “My love to all who love their neighbors. I have asked to be spared from having any weak or hypocritical prayers made over me when I am publicly murdered, and that my only religious attendants be poor, little dirty, ragged, bareheaded, and barefooted slave boys and girls, led by some gray-headed slave mother. Farewell! Farewell!”35

“I, John Brown, am quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood. I had, as I now think vainly, flattered myself that without much bloodshed it might be done.” These were the last written words of John Brown, set down the day he died. Uttered in chains and solemnity, spoken in the very shadow of death, its intensity after the wild and puzzling raid, its deep earnestness as embodied in the character of the man, did more than shake the foundations of slavery than a single thing that ever happened in America.36

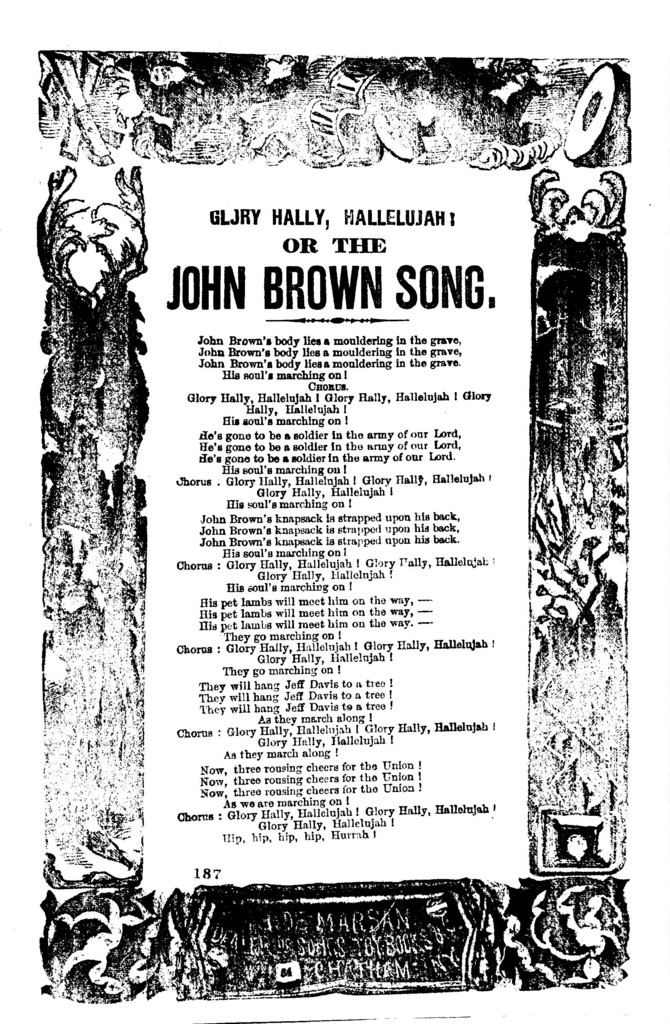

Four years later, as General William Tecumseh Sherman watched regiments of his army march by him from a hill above Atlanta, flames racing through the city below, a band struck up “John Brown’s Body” and the soldiers sang the words lustily. “Never before or since,” Sherman remembered years later, “have I heard the chorus of ‘Glory, glory, hallelujah!’ done with more spirit, or in better harmony of time and place.” To be sure, John Brown did not cause the Civil War, but he hastened its coming. For thousands and tens of thousands in the North, John Brown’s martyrdom sanctified his cause and war itself.37

- Elijah Avey, The Capture and Execution of John Brown: A Tale of Martyrdom (Elijah Avey, 1906), 83. ↵

- Richard Hinton, John Brown & His Men (Scituate: Digital Scanning, Inc., 2001), 139. ↵

- Richard Hinton, John Brown & His Men (Scituate: Digital Scanning, Inc., 2001), 24. ↵

- Jack J. Cardoso, “John Brown,” in Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia (Salem Press, 2022). ↵

- W. E. B. Du Bois, John Brown (Philadelphia: G.W. Jacobs & Co., 1909), 25. ↵

- W. E. B. Du Bois, John Brown (Philadelphia: G.W. Jacobs & Co., 1909), 26. ↵

- Robert E. McGlone, John Brown’s War against Slavery (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 9. ↵

- Robert E. McGlone, John Brown’s War against Slavery (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 10-11. ↵

- Robert E. McGlone, John Brown’s War against Slavery (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 12. ↵

- Robert E. McGlone, John Brown’s War against Slavery (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 198. ↵

- Robert E. McGlone, John Brown’s War against Slavery (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 199-200. ↵

- William T. La Moy and F. B. Sanborn, “The Secret Six and John Brown’s Raid on Harpers Ferry: Two Letters,” The New England Quarterly 88, no. 1 (2015), 142–143. ↵

- L. Diane Barnes, Frederick Douglass: Reformer and Statesman (New York: Routledge, 2012), 82. ↵

- Jay P. Childers and Lisa M. Corrigan, “The Racial Shock of Abolitionist John Brown,” The Quarterly Journal of Speech 109, no. 3 (2023), 261. ↵

- Jay P. Childers and Lisa M. Corrigan, “The Racial Shock of Abolitionist John Brown,” The Quarterly Journal of Speech 109, no. 3 (2023), 261. ↵

- Robert E. McGlone, John Brown’s War against Slavery (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 206. ↵

- Robert E. McGlone, John Brown’s War against Slavery (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 206. ↵

- Robert E. McGlone, John Brown’s War against Slavery (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 207. ↵

- Robert E. McGlone, John Brown’s War against Slavery (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 208. ↵

- W. E. B. Du Bois, John Brown (Philadelphia: G.W. Jacobs & Co., 1909), 308. ↵

- Elijah Avey, The Capture and Execution of John Brown: A Tale of Martyrdom (Elijah Avey, 1906), 118. ↵

- Elijah Avey, The Capture and Execution of John Brown: A Tale of Martyrdom (Elijah Avey, 1906), 119. ↵

- Elijah Avey, The Capture and Execution of John Brown: A Tale of Martyrdom (Elijah Avey, 1906), 122. ↵

- Elijah Avey, The Capture and Execution of John Brown: A Tale of Martyrdom (Elijah Avey, 1906), 123. ↵

- Elijah Avey, The Capture and Execution of John Brown: A Tale of Martyrdom (Elijah Avey, 1906), 127. ↵

- Elijah Avey, The Capture and Execution of John Brown: A Tale of Martyrdom (Elijah Avey, 1906), 128-129. ↵

- Elijah Avey, The Capture and Execution of John Brown: A Tale of Martyrdom (Elijah Avey, 1906), 130-131. ↵

- Elijah Avey, The Capture and Execution of John Brown: A Tale of Martyrdom (Elijah Avey, 1906), 132. ↵

- Elijah Avey, The Capture and Execution of John Brown: A Tale of Martyrdom (Elijah Avey, 1906), 132. ↵

- Robert E. McGlone, John Brown’s War against Slavery (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 306. ↵

- Robert E. McGlone, John Brown’s War against Slavery (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 312. ↵

- Robert E. McGlone, John Brown’s War against Slavery (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 313. ↵

- Robert E. McGlone, John Brown’s War against Slavery (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 316. ↵

- Robert E. McGlone, John Brown’s War against Slavery (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 317. ↵

- W. E. B. Du Bois, John Brown (Philadelphia: G.W. Jacobs & Co., 1909), 364. ↵

- W. E. B. Du Bois, John Brown (Philadelphia: G.W. Jacobs & Co., 1909), 365. ↵

- Robert E. McGlone, John Brown’s War against Slavery (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 328. ↵

11 comments

Kaitlyn Villanueva

This article about John Brown was very informative. I like how there was usage of background information so the readers could see how this story developed. It was so inspiring to see how passionate he was and what he was willing to sacrifice. The images used share the same power as the words and make this article so very powerful.

arosales11

I loved this article! It elegantly covers the violent context of John Brown’s acts while also discussing how it all relates to the Civil War that occurred years later. The author’s use of sources is not only amazing, but also effective in establishing the credibility of the piece and demonstrating that it is a trustworthy account of these events. As an international student with minimal awareness of historical characters like John Brown, I definitely suggest this article to anybody looking to obtain a better understanding everything that was happening within that time line

Natalia De la garza

This is a great article It clearly explains how John Brown’s personal experiences and strong religious beliefs led him to fight against slavery. It’s a great resource for learning about this important figure in American history.

Jordan Robbins

Hi, through your writing I learned so much about John Brown! He honestly sounded insane with some of the things he did but his story is also very intricate and very interesting. His story will most likely live on as a legend. Thank you for posting this story! What made you study about him?

Alysia Cano

This article provides a brilliant and accessible exploration of John Brown’s raid, effectively connecting it to the broader context of the Civil War and the fight against slavery. The extensive use of credible sources enhances its reliability, making it an invaluable resource for anyone seeking to understand this pivotal moment in American history.

Danielle Villanueva

This article about John Brown was fascinating! I learned how deeply he believed in ending slavery and was willing to sacrifice everything for his cause. The detailed account of his raid on Harpers Ferry showed his passionate commitment to freedom. I’m curious how historians today view his complex legacy of violent resistance against slavery.

kmartinez62

I loved this article and all of the detail it provided! I knew about John Brown, but reading about his sacrifice- especially losing his sons in the fight, made it all more powerful. Such a good read!!

Megan Lexi Maldonado

I loved how descriptive and beautiful this article was, it does a great job of educating and deeply moving the reader, making it a truly impactful piece. I find Brown’s perseverance to the cause inspiring, thanks to how his experiences and tasks are worded. The author has done an excellent job of capturing the essence of Brown’s commitment to the cause of freedom (despite all his losses). Brown’s story is a powerful reminder of the sacrifices we must make in the fight for justice, and I wish it was spoken about more often.

Adolfo Duran

This article is simply brilliant. The author seamlessly explores the violent context behind John Brown’s actions while also explaining how it all ties up to the Civil War that took place years later. The number of sources used by the author is not just impressive, but also effective in evidencing the credibility of the article, proving it’s a trustworthy account of these events. As an international student with little knowledge of historical figures such as John Brown, I would strongly recommend this article to anyone trying to have a deeper understanding of the fight against slavery in the US.

Adolfo Duran

This article is simply brilliant. The author managed to explain the reasoning behind John Brown’s infamous raid while seamlessly exploring all the repercussions of his actions. As an international student with little knowledge of anti-slavery figures such as John Brown, I can say that this article is of immense value to anyone trying to grasp the full context behind the Civil War and the fight against slavery. Also, the number of credible sources used by the author evidences the reliability of what’s being told, making the article just all the more captivating. A thorough yet straightforward examination of John Brown’s contribution to the fight for freedom.