The Han dynasty in China lasted from 206 BCE to 220 CE and was ultimately brought down by the conflict that came from the Yellow Turban Rebellion and dynasty’s own inability to keep control of its territory. While the Han Dynasty was strong for the most part, the rebellion was caused by the common people’s dissatisfaction in the government, the religious movement of Daoism, and the general impression that the government had lost its power.1

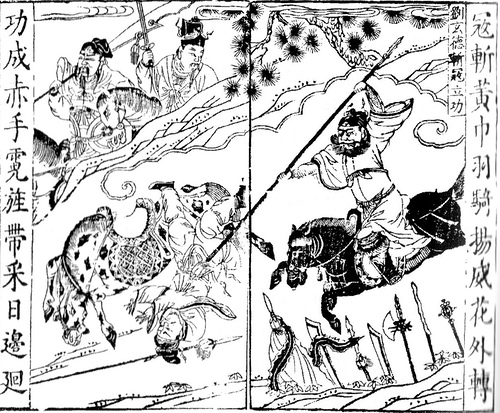

The leader of the Yellow Turban Rebellion was a man named Zhang Jue, who was not a military person or government official, but rather a religious leader. At the same time Daoism was becoming increasingly popular through China, he received a revelation of a new era of the Han Dynasty.2 The “yellow heaven” was going to replace the existing government and last for the next sixty years. Around the year 175 CE, he and his disciples went out throughout central and eastern China. Zhang Jue gained fame by healing the sick and organizing worship. He healed followers through group confession and doses of water infused with the ashes of talismans.3 He and his two brothers amassed a following in the ten years before the start of the rebellion. They wanted to create a utopian state different from the current Confucian form of government. This group would come to be known as the Yellow Turbans because they wore yellow kerchiefs on their heads, keeping in line with the theme of the yellow heaven.4

Much like the Yellow Turban movement, it was common for the succeeding regime to adopt their own religion for the dynasty or the general population to do so. The Han Dynasty itself adopted Confucianism as the official ideology after the fall of the Qin. Likewise, the Sui Dynasty that came after the Han readopted Confucianism as the imperial ideology. Buddhism and Daoism were still practiced during this time, but Confucianism, as in the beginning of the Han dynasty, meant officials would be judged and appointed on their merits over any other basis. This practice led other dynasties to allow the practice of other religions while keeping Confucianism at its core.5

By the year 184 CE, Zhang Jue had appointed himself and his two brothers the generals of Heaven, Earth, and Man. However, even though their large following consisting of over one-hundred-thousand people, they were defeated that same year. While not stopping the rebellion immediately, an informant warned the government of the oncoming events, weakening the rebellion and forcing it to begin ahead of time it had planned. The Yellow Turbans would still live on, as the entirety of the rebellion was not stopped until 205 CE, and new leaders would emerge for the movement.6

One of these later leaders was Ma Xiang, a local of the southwest region that had no ties to the rest of the Yellow Turban Rebellion. In contrast to the earlier movement, however, his followers seemed to be motivated more by the perception that the imperial government was corrupt and not worthy of ruling. Historically, the Han Dynasty had a bad track record of appointing relatives and even infant emperors instead of qualified officials. Since some emperors would have several children with several wives, there was a constant manipulation of each mother trying to get her own sons on the throne. After emperor Zhang died, almost all Han emperors were chosen in their early teens.7 With this negative view of the current political regime, the rebels attacked local officials associated with the imperial government. One of their first targets was a local inspector named Xi Jian. The Han government had sent out a representative, Liu Yan, to have this same official step down due to his burdensome taxation over the locals. However, the representative never arrived, possibly due to his fear of the rebellion. While the Yellow Turbans did finally kill Xi Jian, the assassination only brought to light the imperial government’s lack of control. Yes, the government did know of the problem, but were unable or unwilling to act, and the people had to take matters into their own hands. These rebels were described as “peasants exhausted from their labor,” which was especially true when considering the extra amount of labor they did for the government, such as working on roads and buildings.8 This group was not motivated by Daoism or by the idea of the “yellow heaven,” but they were still quick to join the rebellion and take on the Yellow Turban name.9

A common theme throughout Chinese history and its dynasties was the loss of a dynasty’s “mandate” to rule as perceived by the masses. The Ming Dynasty also fell to a rebellion. Rebels arose then too, due to problems with the government not being able to help during a time of unemployment and famine. Sound familiar? Furthermore, the Qin Dynasty suffered from problems just like those of the Ming. Over exhausted laborers, forced labor, and high taxes led them to seek a change. It seems this would be a primary issue that the Han dynasty would want to avoid.10

The sect of Yellow Turbans that rebelled in the west area of the Han dynasty was also quickly defeated. Quite possibly this could have been attributed to their lack of structure and leadership. Even among other people, these Yellow Turbans could have been viewed as villains. In one account, when a band of rebels attacked a town, they not only aimed for the politicians, but acted as bandits and attempted to kidnap the women. Three women were so hopeless that they decided to drown themselves in a river rather than be captured. That is not the image a rebellion would want to uphold.11 However, even in their defeat, their motivation was emphasized. The imperial government did not have the manpower or resources to successfully suppress the rebellion on their own, so they enlisted the help of a local elite, namely Jia Long, who had a personal army. While on his way to meet Mi Xiang’s army, he rallied more men and defeated Mi Xiang. Following these events, Liu Yan tried himself to seize power and was defeated. This further exposed the lack of authority throughout the Han Dynasty and the local governments.12

So while the Yellow Turban rebellion can be seen as a failure on the part of the rebels, it is also a failure in the eyes of the imperial government. When analyzing the reasons for the rebellion, more importantly, for the lack of authority and distrust in the government, the rebellion further emphasized that lack and distrust, and fixed nothing. The government was too weak to deal with the rebellion on its own and enlisted the help of powerful people and families for military support. The result of this was that the victorious military leaders took advantage of the further weakened Han Dynasty and seized its power. The resulting three states would fight constantly and left China in a period of disunion known as the second Period of the Warring States.13

In other dynasties in China, whenever the current rulers were deemed unfit by a group hoping to seize power, the claim was made that the ruling dynasty had lost the mandate of heaven. Much like the Yellow Turban Rebellion, other groups would claim that they could rule better than the current dynasty and would attempt to seize the throne. The first to use the mandate of heaven claim was the Zhou Dynasty. The Zhou rulers overthrew the previous Shang Dynasty and claimed the Mandate of Heaven. Their method for claiming legitimacy influenced all later dynasties. However, to successfully lay claim to the Mandate one would have to overthrow the current rulers and be successful in their subsequent rule.14

The Han Dynasty was plagued with problems and inner turmoil. It had a weak government and the people wanted change. However, even the people’s rebellion was somewhat unorganized and weak. The Yellow Turban Rebellion’s founding leaders were killed within a year but the rebellion still lasted for many years after that. In the end, the rebels didn’t put up a strong enough fight to successfully install their “yellow heaven,” but they weakened the Han Dynasty so much it split and the region would not be unified again until the Sui Dynasty in 589 CE.

- Funk & Wagnalls New World Encyclopedia, 2016, s.v. “China.” ↵

- Encyclopedia of Religion, 2005, s.v. “Zhang Jue,” by Lindsay Jones. ↵

- Howard Levy, “Yellow Turban Religion and Rebellion at the End of Han,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 76, no. 4 (December 1956): 216. ↵

- Encyclopedia of Religion, 2005, s.v. “Daoism: An Overview,” by Stephen Bokenkamp. ↵

- Funk & Wagnalls New World Encyclopedia, 2016, s.v. “China.” ↵

- Howard Levy, “Yellow Turban Religion and Rebellion at the End of Han,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 76, no. 4 (December 1956): 217-220. ↵

- Li Feng, Early China A Social and Cultural History (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 300. ↵

- Martin Wilbur, Slavery in China during the Former Han Dynasty (Chicago: Field Museum of Natural History, 1943), 34. ↵

- Michael Farmer, “The Three Chaste Ones of Ba: Local Perspectives on the Yellow Turban Rebellion on the Chengdu Plain,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 125, no. 2 (June 2005): 194. ↵

- Funk & Wagnalls New World Encyclopedia, 2016, s.v. “China.” ↵

- Funk & Wagnalls New World Encyclopedia, 2016, s.v. “China.” ↵

- Michael Farmer, “The Three Chaste Ones of Ba: Local Perspectives on the Yellow Turban Rebellion on the Chengdu Plain,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 125, no. 2 (June 2005): 194. ↵

- Funk & Wagnalls New World Encyclopedia, 2016, s.v. “China.” ↵

- Funk & Wagnalls New World Encyclopedia, 2016, s.v. “China.” ↵

24 comments

Tyler Sleeter

Great article with lots of information. It was interesting to me that the leader of the movement was a religious person and that they got their name from the yellow kerchief worn on their heads. I did not realize that it was common for the ruling party to pick their own religion, but I suppose since there were so many religious schools of thought at the time, it makes sense. It seems odd to me that someone could appoint himself and his brothers the leaders of heaven, earth, and man since at least two of things cannot be controlled.

Karina Nanez

It is always very interesting to read about rebellions and uprising of ancient people. These “Yellow Turban” men were very interesting to read about, it seems crazy to us now that there would be political rulers chosen by god and given a mandate of heaven. But this Yellow Turban rebellion has proven that this sort of ruling does not always match what the people want.

Samman Tyata

Great article! I really liked the way how you have managed your article. I was amazed to know that the leader of the Yellow Turban Rebellion was not a military person or government official, but rather a religious leader. It was interesting to read that the founding leaders were killed; however, the rebellion still lasted for many years.To sum it up, it was a good and informative read.

Osman Rodriguez

Cool article. I never heard about the ‘yellow heaven’. It is true that many of China’s dynasties came to be because of an apparent ‘mandate of heaven’. That they, for some reason, had the divine right to rule. I find it interesting that people would not challenge the notion of such a a proclamation. Its interesting that Zhang Jue, and other daoist, formed a rebellion. It seems that Daoism is itself, very weird.