On what should have been a joyous Christmas day in 1917, a devastating ranch raid occurred at Brite Ranch in Presidio County, Texas. The Brite Ranch raid was part of a series of raids by Pancho Villa’s Villistas, which had escalated in Texas since the start of the Mexican Revolution. With each raid, there were more and more deaths. After each raid, the tensions between Anglo Texans and Mexican Texans rose. The raid at Brite Ranch ended with the sudden murder of an Anglo postman. The scapegoats for the raid soon became peaceful Mexican Americans in the small farming town of Porvenir, Texas. In the following months, the Brite Ranch raid would come to drastically change the lives of the residents of Porvenir and become the starting point of a brutal marker in Mexican-American history. 1

The story of Brite Ranch and its devastating outcome cannot be described without mentioning the Texas Rangers and Anglo hostility towards Mexican Americans living in Texas. In 1823, the Texas Rangers began as a group of citizen soldiers. Stephen F Austin is said to have organized the Rangers as protection against Native American raids in Texas.2 As tension between Anglos and Mexicans grew, the Texas Rangers took it upon themselves to “protect” Anglos from Mexicans and Mexican Americans. The Texas Rangers offered protection to Anglos in Texas but projected violence towards Mexicans. The Rangers continued as a group of citizen soldiers until 1874. As states on the United States-Mexico border became more susceptible to violence, the Rangers gained popularity among Anglo Texans. On April 10, 1847, the Texas legislature created the frontier battalion, the first formal organization of the Texas Rangers. During and following the Mexican revolution, problems escalated even further on the United States-Mexico border in Texas.3 Over the nineteenth century, Anglos had come to dominate the United States-Mexico border area both economically and politically. Anglo domination opened the doors for the Rangers to use raids to justify killing anyone who looked Mexican. Mexicans were frequently murdered or banished regardless of their innocence.4

In the years from 1910 through 1920, innocent Mexican Americans in Texas became increasingly vulnerable to lynching, torture, massacre, and other violence. Mexicans in Texas found themselves at the heart of unjust situations that were backed by both the Texas government and the federal government. At the root of the violence stood white mobs, and, most importantly, law enforcement agencies such as the Texas Rangers. Anglo mobs and the Rangers’ violence typically came from rumors about a crime that was often pinned on Mexican Americans. In many circumstances, Mexican Americans were innocent of the crimes they were blamed for, but blaming crimes on them allowed for racial terror to continue. In 1910, Antonio Rodriguez was accused of killing a white woman. Rodriguez received no trial and was instead kidnapped from jail and murdered by a white mob.5 Stories like Antonio’s were not uncommon, especially in Texas. It became apparent that among states across the United States-Mexico border, Anglo Texans were considered to have the most hostility towards Mexicans.6 In 1915, there came a substantial increase in violence towards Mexican Americans by the Rangers. That year, James E. Ferguson became governor of Texas and he increased the presence of the Rangers in the state. New recruits of the Texas Rangers were well versed in the use of weaponry and horseback riding, but were not by any means unbiased in their efforts in law enforcement. It quickly became evident that the Rangers blurred the lines between law enforcement, vigilantism, and enacting racial terror against Mexicans. A push for the Rangers to continue their terror came on July 20, 1915, when Governor Ferguson instructed Henry Lee Ransom, the head of the Rangers, to stop crime by any means, even if it meant they had to kill every Mexican in the state.7

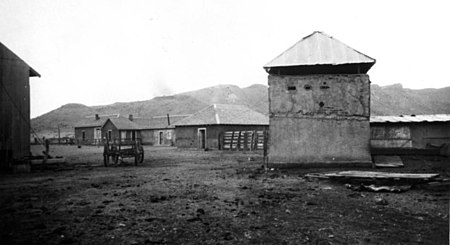

On December 25, 1917, the Brite Ranch raid occurred. During the raid, an Anglo postman was killed, and Mexicans in the small town of Porvenir became scapegoats for the murder. The kind people of Porvenir were accused of both helping and housing the raiders, despite there being little evidence to back up the claim. One source at the time accused the people of Porvenir of being “thieves, informers, spies, and murderers.”8 In reality, the people of Porvenir were not bandits or outlaws, nor did they have anything to do with the Brite Ranch raid. The people of Porvenir were simple farmers who were trying to make a life for themselves in Texas where they could escape the insecurity of the Mexican revolution.9 The Texas Rangers became furious over the killing of the Anglo postman and the supposed involvement of Porvenir in the Brite Ranch raid. The Rangers took law enforcement matters of the raid into their own hands. On January 24, 1918, Texas Rangers from Company B arrived in Porvenir and surrounded the town. At gun point, the Rangers ordered the residents of Porvenir out of their homes. Struck with fear, the residents of Porvenir complied with the Rangers’ orders. The Rangers gathered around two dozen men and searched their homes, but found nothing in relation to the Brite Ranch raid. The people of Porvenir had some old guns, but no horses from Brite Ranch, or any other stolen goods. The innocent people of Porvenir were relieved that their run-in with the Rangers was over. Unfortunately, the town of Porvenir would soon face more terror than they could have imagined.

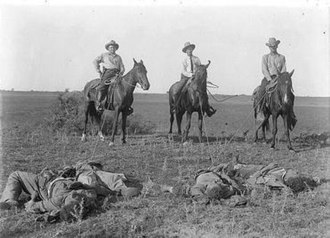

A few days later, in the very early morning of January 28, 1918, a group of Texas Rangers returned to Porvenir and claimed that they still had suspicions that the townspeople took in and helped the raiders of Brite Ranch. With the help of U.S. cavalry soldiers, the Rangers once again surrounded Porvenir. The rangers took fifteen unarmed men and boys of the ages 16 to 72 into custody.10 With no resistance from the men and boys, the Texas Rangers marched the fifteen unarmed individuals to a rock near the town’s river. For ten seconds there was nothing but silence; then, the gunshots went off. Through the gunshots, women in town began to scream at the top of their lungs. Following the women’s screams, children began to cry with fright. The people of Porvenir soon started to pray in despair as they fled from their homes in Texas.11 Antonio Castaneda, Longino Flores, Pedro Herrera, Vivian Herrera, Severiano Herrera, Manuel Moralez, Eutemio Gonzalez, Ambrosio Hernandez, Alberto Garcia, Tiburcio Jaques, Roman Nieves, Serapio Jimenez, Pedro Jimenez, Juan Jimenez, and Macedonio Huertas were the names of the fifteen unarmed bodies of men and boys that laid lifeless in the bush next to the river as the Rangers rode away.12

On the morning of the massacre, the survivors of Porvenir fled across the Rio Grande to Pilares, Mexico, where they would remain, far from the terror they endured at the hands of the Texas Rangers.13 The day following the massacre, the local schoolteacher of Porvenir, Henry Warren, discovered the bodies of the fifteen men. Warren described that the bodies had remained fallen where they were murdered. He described that the Rangers “took the men from their warm beds” to be killed.14 Juan Flores, who was thirteen at the time, returned to Porvenir to find the mutilated body of his father laying among the fourteen other corpses. Flores had nightmares for the rest of his life. Other survivors of the massacre soon turned to suicide to cope with the horror they had experienced on that day.15 In the late morning of January 28, an old woman from Porvenir returned from Pilares to gather the bodies of the massacred victims. The woman took the bodies back to Pilares, where they would later receive a proper burial. The day following the massacre, the Rangers reappeared in Porvenir to burn the village to ashes. A town that once belonged to 140 people became dust in a matter of two days. The people of Porvenir were not at Brite Ranch, nor did they assist the raiders on that Christmas day of 1917. The lives of fifteen innocent victims were lost at the hands of the Texas Rangers. Brite Ranch was forty miles away; there was no road in between the ranch and Porvenir, and no evidence of stolen goods was ever found.16

The terror in Porvenir was the last straw for Texas Representative Jose T. Canales. He demanded change, specifically regarding the Texas Rangers. He explained that the Rangers no longer had a moral or ethical ground in their position as law enforcement. Unfortunately, Canales did not have an easy time opposing the Rangers. Frank Hamer, a Texas Ranger, threatened Canales and his family with physical violence shortly after Canales spoke out.17 Fortunately, the fear that Hamer attempted to instill in Canales did not work. Canales wrote to Congressman John Nance Garner, requesting intervention from the federal government in the case of the Texas Rangers. Canales requested for the Rangers that were responsible for various murders in Texas, to be held accountable and be removed from their positions in law enforcement. Canales’ letter reached the White House, but the response was short of promising. The response Canales received stated that the Rangers played an important role in the safety of Texas and that although their methods were “not always in conformity with strict judicial procedure,” they should remain in Texas.18 The response that Canales received both disregarded the many victims of the Rangers and excused the Rangers’ acts of intense violence.

Despite the unfortunate response from the U.S. government, Canales’ efforts did not stop. On January 15, 1919, Canales introduced House Bill 5, which was later known as the Canales Bill. The bill aimed to establish guidelines for new recruits to the Rangers. The guidelines explained that the Rangers should be at least twenty-five years old, have proof of their moral temperament, and have at least two years of experience in law enforcement. The Canales Bill also allowed for civil lawsuits to be filled against the Rangers.19 Once again, Canales was met with disregard for the Rangers’ actions and excuses for their unjust behavior. Representative Barry Miller of Dallas argued that Canales’ bill diminished the effectiveness of the Rangers.20

Canales’ efforts reached their peak on January 30, 1919, when an investigation of the Texas Rangers opened at the state capitol. Canales filed 19 charges against the Texas Rangers in relation to the various unjustified murders they had been part of, where no arrests of the Rangers had been made. Unfortunately, Canales and the many victims of the Rangers were once again let down by the state and federal government. On February 13, 1919, the legislative hearings ended. The Rangers were absolved of any wrongdoing, and it was determined that they should continue their efforts in Texas.21

Canales’ efforts proved to be undermined by state and federal authorities, but his efforts did bring about some optimism. The attention that Canales brought to the issue of the Rangers caused significant change in the Rangers’ selection of new recruits. A few years after the hearings, the Rangers put into practice policies that Canales had suggested. Porvenir caused a breaking point for Canales and because of his efforts, racial terror by the Texas Rangers slowly began to decrease.22

Today, a plaque stands in the town of Porvenir as the last reminder of a town that once was. It stands as an echo of the brutal history that Mexican Americans faced in Texas. The sign recognizes the victims of the massacre as well as the terror that the people of Porvenir experienced. The plaque is a reminder of the cruel racial terror of the Texas Rangers, a group that is still recognized as the heroic law enforcement of Texas. Porvenir remains a ghost town that holds the memories of a ranch town that once flourished but ended abruptly in blood, tears, and flames.

- Russell Contreras and Cedar Attanasio, “Mexican Americans Faced Racial Terror from 1910-1920,” The Toronto Star, July 26, 2019, https://www.thestar.com/news/world/us/2019/07/26/mexican-americans-saw-own-racial-terror-before-red-summer.html. ↵

- Victoria Smith, “The Canales Investigation: A Turning Point for the Texas Rangers,” The Measure: An Undergraduate Research Journal, 4 (2020), 110. ↵

- Victoria Smith, “The Canales Investigation: A Turning Point for the Texas Rangers,” The Measure: An Undergraduate Research Journal, 4 (2020), 110 ↵

- Brent M. S. Campney, “‘The Most Turbulent and Most Traumatic Years in Recent Mexican-American History’ : Police Violence and the Civil Rights Struggle in 1970s Texas,” The Southwestern Historical Quarterly 122, no. 1 (July 1, 2018): 32–57. ↵

- Russell Contreras and Cedar Attanasio, “Mexican Americans Faced Racial Terror from 1910-1920,” The Toronto Star, July 26, 2019, https://www.thestar.com/news/world/us/2019/07/26/mexican-americans-saw-own-racial-terror-before-red-summer.html. ↵

- Brent M. S. Campney, “‘The Most Turbulent and Most Traumatic Years in Recent Mexican-American History’ : Police Violence and the Civil Rights Struggle in 1970s Texas,” The Southwestern Historical Quarterly 122, no. 1 (July 1, 2018): 32–57. ↵

- Victoria Smith, “The Canales Investigation: A Turning Point for the Texas Rangers,” The Measure: An Undergraduate Research Journal, 4 (2020), 111 ↵

- Russell Contreras and Cedar Attanasio, “Mexican Americans Faced Racial Terror from 1910-1920,” The Toronto Star, July 26, 2019, https://www.thestar.com/news/world/us/2019/07/26/mexican-americans-saw-own-racial-terror-before-red-summer.html. ↵

- John MacCormack, “Findings Shed New Light on 1918 Porvenir Massacre,” San Antonio Express-News AP Regional State Report – Texas (Associated Press, April 4, 2016), Newspaper Source Plus. ↵

- Brent M. S. Campney, “‘The Most Turbulent and Most Traumatic Years in Recent Mexican-American History’ : Police Violence and the Civil Rights Struggle in 1970s Texas,” The Southwestern Historical Quarterly 122, no. 1 (July 1, 2018): 32–57. ↵

- Russell Contreras and Cedar Attanasio, “Mexican Americans Faced Racial Terror from 1910-1920,” The Toronto Star, July 26, 2019, https://www.thestar.com/news/world/us/2019/07/26/mexican-americans-saw-own-racial-terror-before-red-summer.html. ↵

- Monica Martinez, “Porvenir Massacre,” Texas State Historical Association (website), accessed April 8, 2023, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/porvenir-massacre. ↵

- John MacCormack, “Findings Shed New Light on 1918 Porvenir Massacre,” San Antonio Express-News AP Regional State Report – Texas (Associated Press, April 4, 2016), Newspaper Source Plus. ↵

- Matthew Berkshier, “Porvenir: The Quiet Massacre,” Sul Ross: The Frontier University of Texas (website), accessed February 20, 2023, https://www.sulross.edu/news/porvenir-the-quiet-massacre/. ↵

- Russell Contreras and Cedar Attanasio, “Mexican Americans Faced Racial Terror from 1910-1920,” The Toronto Star, July 26, 2019, https://www.thestar.com/news/world/us/2019/07/26/mexican-americans-saw-own-racial-terror-before-red-summer.html. ↵

- John MacCormack, “Findings Shed New Light on 1918 Porvenir Massacre,” San Antonio Express-News AP Regional State Report – Texas (Associated Press, April 4, 2016), Newspaper Source Plus. ↵

- Victoria Smith, “The Canales Investigation: A Turning Point for the Texas Rangers,” The Measure: An Undergraduate Research Journal, 4 (2020), 113. ↵

- Victoria Smith, “The Canales Investigation: A Turning Point for the Texas Rangers,” The Measure: An Undergraduate Research Journal, 4 (2020), 113. ↵

- Victoria Smith, “The Canales Investigation: A Turning Point for the Texas Rangers,” The Measure: An Undergraduate Research Journal, 4 (2020), 113-114. ↵

- Victoria Smith, “The Canales Investigation: A Turning Point for the Texas Rangers,” The Measure: An Undergraduate Research Journal, 4 (2020), 114. ↵

- Victoria Smith, “The Canales Investigation: A Turning Point for the Texas Rangers,” The Measure: An Undergraduate Research Journal, 4 (2020), 115. ↵

- Victoria Smith, “The Canales Investigation: A Turning Point for the Texas Rangers,” The Measure: An Undergraduate Research Journal, 4 (2020), 116. ↵

44 comments

Kaylah Garcia

Hello! To begin with, congratulations on your nomination. This was a very fascinating and useful essay to read. I didn’t know much about the Texas Rangers’ past in Porvenir, so reading this piece was really upsetting, especially as a Mexican American myself. Now, as for the article itself, I applaud you for writing such a well-written, fluent, and interesting piece. It summed up the story concisely but efficiently, and its conclusion was captivating! It made me feel goosebumps. Overall, excellent work!

David Duron

This article provides a detailed and thought-provoking account of the devastating impact of racial violence and terror on Mexican Americans living in Texas during the early 20th century. The author’s careful research and analysis effectively highlight the role of law enforcement agencies such as the Texas Rangers in perpetuating racial terror against innocent Mexican Americans. The tragic events surrounding the Brite Ranch raid and its aftermath underscore the urgent need for greater understanding and recognition of the ongoing struggles faced by marginalized communities in the United States.

Iris Reyna

Congrats on your article nomination Jared, the article was a very informative and interesting read. It was fascinating to hear more about the Texas Rangers and the origin of the group. It was sad to hear about the suffering of Antonio Rodrigez. I liked the angle that you took on the Texas Rangers because in the light they are seen as good and you only hear good about them.

Melyna Martinez

Hello, this article is amazing at showing a darker side of history such as the Texas Rangers. The reality that this group had the power and authority and they abused it for their own will. During this time we hear much about slavery and the treatment of African Americas but tend to forget other minorities. Mexican Americans failed to the abuse of the Texas Ragers and with that caused the death of many based on someone’s race.

Bryon Haynes

Congratulations on the nomination! The article definitely deserved it as it gave me a chance to learn more about the Texas Rangers as someone who isn’t a Texan native. I didn’t know there was such an interesting story within their history and I’ve learned a lot about how previous rangers have definitely left a dark mark.

Abbey Stiffler

Congrats on the nomination of your article. It’s fantastic that you wrote about a subject that is so crucial but rarely discussed. Rarely have I heard anything about the Texas Rangers. This article provided a wealth of information regarding the struggles that the early Mexican Americans faced. The Texas Rangers are one of the state of Texas’s allegedly most trustworthy police enforcement organizations, therefore this incident did not go well for them.

D'vaughn Duran

Congratulations on being nominative! This was a great article with amazing information about the topic. I didn’t know this information and the title caught my attention. When reading this article and the structure of the article it is well written. It shows the Texas Rangers and the abuse of power. I never heard about this information till I read this. This information was very engrossing.

Osondra Fournier-Colon

The battle between Anglo and Mexican Texans is glossed over in Texas history, usually pinning the Anglos as the good and the Mexicans as the bad. This article shows a different perspective on that conflict and that the Anglos and the Texas Rangers were not the outstanding heroes as most history portrays them. I love your description of the discrimination and scapegoating during these times. Great article!

Barbara Ortiz

Congratulations on your nomination for such a great article. Since I moved to Texas almost 4 years ago, I have really tried to immerse myself in learning more about Texas history and culture (the good, bad and ugly). And with roots in Mexico, these kind of stories are hard to read, but we need to get them out there for people to know the atrocities.

Kristen Leary

Congratulations on a well written article and on your nomination! Surely it was well deserved. The story you told is such a tragic one that I’m sure few Texans even have ever heard. I think you did well in your descriptions and it is evident that much research went in to craft this article. It was an interesting story and I think you told it well. Well done!