Winner of the Spring 2018 StMU History Media Award for

Best Article in the Category of “Gender Studies”

“La Adelita” was one of the most popular corridos, or songs of romance, during the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920).1 This song is the love story of a young woman who travels with a sergeant and his regiment during the revolution.2 The song praises Adelita, the sweetheart of the troop, for both her beauty and her valor, noting how she is wanted by the other soldiers. We can imagine this woman as an object of desire, whose beauty and physique attracted the soldiers, and eventually broke their hearts. But this description is actually… incorrect.3

The Adelita, also known as soldadera, or female soldier, is the term used to describe women who contributed to many aspects of the Mexican Revolution. These women worked as nurses, food providers, lovers, spies, messengers, and fighters.4 In fact, some reached the rank of colonel and general. Many of them were forced by their husbands to follow them and work in the camps, but there were also those who volunteered to join the cause.5 Today, soldaderas are remembered as strong and courageous women who took up weapons and became fighters, often having to cut their hair and dress to appear like their male counterparts, because of the oppressive gender inequality prevalent in the Mexican society of that time.6 There is one soldadera in particular, Petra Herrera, also known as La Guerrera, and as La Generala (female general), who joined the cause and fought with the strongest of the soldiers. But what inspired women to join their male counterparts to fight this war, and why did the revolution even happen?

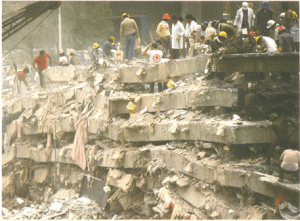

To answer this question and to be able to understand why these women now make up a very important aspect of Mexico’s history and its formation as a country, we need to go back in time to 1876, when the general and politician Porfirio Díaz became president. Porfirio Díaz was known to be a corrupt, elitist president, who favored wealthy landowners, industrialists, and foreign interests.7 The country was also known for the slave-like conditions rural people faced while working on the haciendas owned by wealthy landowners.8 These rural workers were very dissatisfied with the lack of voice they had in the government. But the precipitating event that sparked the revolution was Díaz’s announcement, in 1908, that he would run for his seventh term as president in 1910. This caused controversy among the people who had been suffering from his long regime. Francisco I. Madero then rose as the leader of the Antireeleccionistas (Anti-Reelection alliance). Madero subsequently announced that he would be running for president against Díaz. This prompted the mobilization of armies throughout Mexico. Countless leaders, such as Pascual Orozco and Pancho Villa, began raiding government garrisons as part of an uprising to remove the current president and eventually, elect a new president for the country.9 These were some of the events that inspired and sparked the courage of not only men but of women as well, to join the armies and fight for the shared goal of overthrowing Díaz’ dictatorship and make democracy in Mexico a reality.10

Petra Herrera witnessed the suffering of her country and decided to take action. She witnessed the harshness of landowners and the terrible conditions in which workers lived. She knew that the government had to change from being a corrupt one to being a democratic and fair one. But how would she help? Women at that time faced strict social prohibitions that kept them from playing important roles in the workforce. Instead, they were expected to be caregivers, stay at home, and take care of their children. Women were seen as precious and delicate, something that could not blend with the harshness of war. Petra, instead of following that norm, disguised herself as a man and started calling herself “Pedro Herrera” in order to join the revolutionary troops of Pancho Villa.11

During her time in the camp, she had to lie to her fellow soldiers in order to protect her identity. For example, she would lie that she shaved at dawn before the other soldiers woke up.12 Because of this, “Pedro” was able to blend in perfectly. Quickly after her joining the army, Petra was recognized as an aggressive fighter who carried out military operations efficiently and strategically. In disguise, she came to be known as a courageous and brave soldier, and was soon praised for her intelligence and her skills at blowing up bridges.

Thanks to the acknowledgment she faced on behalf of her peers and her establishment as a strong soldier, Petra decided she would confess her true identity. She believed this would not affect her position or status in the militia, and that she would be accepted and even promoted to general. But sadly, when she told the truth, she was removed from the army instead.13 Consequently, she decided to organize a group of women who were likewise removed from combat, even after they had fought courageously for the same cause as their male counterparts. Petra decided not to give up, and she organized a group of more than four hundred women with the same motive: to put an end to the current presidency and the hardships that Díaz had imposed on the citizens. Her militia not only fought in several battles, but Petra united these fighting women with Pancho Villas’ forces, despite his denial of them fighting and bearing arms. Together, they were able to take the city of Torreón on May 30, 1914, which had been a military base for Díaz’s central federation.14 At the end of the fight, she requested General Castro, a leader of the revolution, to allow her to re-enter the military and make her general, but he only granted her the title of colonel and disbanded her woman’s brigade.15 But her work did not end there. After the demobilization of the woman’s militia, Petra decided to join Venustiano Carranza, one of the main political leaders of the revolution who later became president of Mexico. She became a spy for him and worked as a bartender in Jimenez, a city in the northern part of Mexico.16 But while she was working there, she was shot three times by a group of drunk men, later dying from the injuries.

Despite the effort and the work Petra Herrera gave for the revolution, she has barely received any acknowledgment as a soldadera. There are several causes for this. Men during those times had mixed feelings about women being in combat and the role they had in the fight.17 One of the most passionate opponents of women joining the militia and bearing arms was Pancho Villa. He viewed women as liabilities to an army’s offensive strategy and combative potential, even though Petra Herrera and other great female combatants fought at his side several times to free the country from the oppressive presidency.18 There was also the idea that soldaderas were just images of romance during the Mexican Revolution, such as the song of “The Adelita,” contributing to recognizing only a few of them as strong fighters and contributions to this era.19 These women should be acknowledged and we should grant them a higher praise because many were forced to take this role of soldaderas after being abducted and often raped by revolutionaries who invaded their towns and cities. At the end of the day, the labor and effort of women such as Petra were very important factors for what we have come to know as the Mexican Revolution.

Hear the ballad of La Adelita

La Adelita

Spanish20

Little Adela

English translation21

- Beatriz de León, “La Adelita: El Rostro de La Soldadera,” in Reforma (Mexico D.F., Mexico), 2010. ↵

- Beatriz de León, “La Adelita: El Rostro de La Soldadera,” Reforma (Mexico D.F., Mexico), 2010. ↵

- Andrés Reséndez Fuentes, “Battleground Women: Soldaderas and Female Soldiers in the Mexican Revolution,” The Americas, no. 4, (1995): 55-57. ↵

- Oxford Research Encyclopedias, May 9, 2016, s.v. “Working Women in the Mexican Revolution,” by Susie S. Porter. ↵

- Donna Seaman, “Las Soldaderas: Women of the Mexican Revolution,” Booklist 103, no. 12, (2007): 18. ↵

- Elizabeth Salas, Soldaderas in the Mexican Military: Myth and History (Austin, Tex.: University of Texas Press, 1990), 48-49. ↵

- Encyclopedia Britannica, October 25, 2017, s.v. “Mexico | History, Geography, Facts, & Points of Interest – The Mexican Revolution and Its Aftermath.” ↵

- Encyclopedia Britannica, January 2, 2018, s.v. “Mexican Revolution | Causes, Summary, & Facts.” ↵

- Encyclopedia Britannica, January 2, 2018, s.v. “Mexican Revolution | Causes, Summary, & Facts.” ↵

- Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, January 2008 v.s. “Women,” by Francesca Miller and Meredith Glueck. ↵

- Delia Fernandez, “‘La Adelita’ Becomes an Archetype of the Mexican Revolution,” McNair Scholar Journal, Vol. 13, (2009): 57-58. ↵

- Jason Porath, Rejected Princesses: Tales of History’s Boldest Heroines, Hellions, and Heretics, (New York, NY.: Patreon, 2016), 123-124. ↵

- Elena Poniatowska, Las soldaderas: women of the Mexican revolution (El Paso: Cinco Punto Press, 2006), 45. ↵

- Encyclopedia Britannica, October 25, 2017, s.v. “Mexico | History, Geography, Facts, & Points of Interest – The Mexican Revolution and Its Aftermath.” ↵

- Jason Porath, Rejected Princesses: Tales of History’s Boldest Heroines, Hellions, and Heretics, (New York, NY.: Patreon, 2016), 123-124. ↵

- Jason Porath, Rejected Princesses: Tales of History’s Boldest Heroines, Hellions, and Heretics, (New York, NY.: Patreon, 2016), 123-124. ↵

- Wilma Mankiller, Marysa Navarro, and Gloria Steinem, “Feminism and Feminisms: Feminism,” in Reader’s Companion to U.S. Women’s History (Boston, 1998), 187. ↵

- Oxford Research Encyclopedias, May 9, 2016, s.v. “Working Women in the Mexican Revolution,” by Susie S. Porter. ↵

- Alicia Arrizón, “Soldaderas and the Staging of the Mexican Revolution,” TDR: The Drama Review 42, no. 1, (1998): 105–107. ↵

- Amparo Ochoa, “La Adelita,” Corridos Y Canciones de la Revolucion Mexicana, Ediciones Pentagrama, 1995. Featured in video “La Adelita – Amparo Ochoa,” Courtesy of Youtube (https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=64&v=hlGtOv-QEQQ ). ↵

- “La Adelita,” Mexican Folk Song, translation of last three stanzas by phantasmagoria ↵

127 comments

Mariana Mata

The credit that is given to Pancho Villa and his men for their success in the Mexican Revolution disturbs me immensely since coming across this article. It is quite upsetting that Villa’s troops displaced such a strategic soldier solely because of her gender. The mention of the song “Adelita” is a great example of historical irony; the women in the song are portrayed as an object of desire when they were feared by the same men they were fighting with.

Citlalli Rivera

Although revolutionaries like Pancho Villa and Fransisco Madero fought a great cause against the tyranny of Diaz, reading this article invoked in me a sense of great anger towards them. Brave and heroic women risked their lives and their societal acceptance to join the revolutionary cause and unconditionally support Villa and Madero just to be thanked with sexism and machismo-ism. After reading that Pancho Villa denounced the fighting women and the disbanding of the woman’s militia by General Castro, I couldn’t help but think that toxic masculinity was so strong and alive in them that they would rather send a woman back to the domestic role than accept her strength and her contribution to getting closer to overthrowing Diaz. Thank you for highlighting Petra Herrera and the amazing work she did! Articles like these reinforce the work that trailblazing women have made instead of letting them be forgotten by their predecessors.

Sara Guerrero

I was very intrigued by the title of this article and when I read this story I was amazed by these women who contributed to the Mexican Revolution in many large ways than I imagined. I also found it interesting that she joined a troop of men by disguising herself and she was able to pull it off. It’s sad that she didn’t receive the recognition for her work, but at least now people are more aware of this kind of hidden history. Great job on this article!

Lesley Martinez

This was a very interesting and informative article about the role that women played during the Mexican Revolution. I’m especially impressed that the lyrics of La Adelita romanticized female soldiers for their beauty and not for their courage to fight in the war. Also, it’s surprising to read that Petra Herrera would change her identity to Pedro, then decide to tell the truth, and when removed as a soldier, she created her own militia. Her death is very tragic, but she made a name for women in the Mexican Revolution and will be remembered for her bravery. Great article!

Hali Garcia

This is a very informative article on Petra Herrera. She is a very brave and remarkable woman who went against the norms of what women were viewed as to fight for her country. It is amazing how she wanted to fight so she joined the military and disguised herself as a man only to be kicked out once she revealed her identity. What struck me the most was when she organized a group of women who had wanted to fight.

Nelly Perez

The beginning of the paragraph really got me hooked until it showed a twist at the end by saying the meaning behind the song “La Adelita” was wrong. The term was used for women who joined the cause during the Mexican-American revolution by volunteering, providing aid, and assisting the troops by being spies to gather intel from the enemy. Petra took action after seeing harassment and unjust actions the president was causing.

Antonio Holverstott

Even though I do not believe in the use of violent force to create a necessary reform to governance when people are oppressed, the role of women as combatants during the Mexican revolution must be acknowledged. They bravely fought against soldiers when others did not want them to participate in military conflict. Because of their involvement, they were able to retain specific settlements when other male soldiers could not perform such tasks.

Samuel Vega

Congratulations on your recognition of “Best Article for Gender Studies.” I thought the article was fascinating and it gave glimpse into women’s role in the Mexican Revolution. These women should be recognized for their role in the fight for democracy in Mexico. The article leaves you questioning how many other wars or revolutions did women play significant roles; but were unrecognized as well. Ending the article with lyrics from the ballad “La Adelita” was a creative touch to the article. I liked the different approach.

Francisco Cruzado

I had never heard before about “Pedro Herrera”, and I am glad today I found out about her! It is always good to have in mind that when a society finds itself in the midst of an upheaval, it certainly involves everybody. It happened in 1883s Peru, and during Independence years throughout Latin-America: women were and are a key part of the building of nations and their basic foundations, but also of the rebuilding of them. Such a song is amazingly beautiful!

Cristianna Tovar

I found it so empowering that Petra Herrera stood up for what she believed in and defied all gender stereotypes. She is a true warrior and is so brave for disguising herself and fighting as a man to make a change in her society. I admire her so much for what she accomplished! Great article!