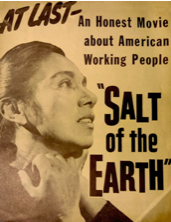

When thinking about the civil rights movements of the 1950s and 1960s, one usually does not think of the blacklisted film Salt of the Earth, the movie that sparked and influenced the Chicano movement. Salt of the Earth was the creation of director Herbert Biberman and screenwriter Micheal Wilson, and was produced with the help of Paul Jarrico.1 Micheal Wilson based the story on the 1951-1952 strike conducted by the International Union of Mine, Mill, and Smelt Workers (UMMSW) against the company Empire Zinc. The majority of the movie was filmed in Silver City, New Mexico. Unlike many other films at the time, Salt of the Earth was narrated by a female character named Esperanza, who was played by the Mexican actress Rosaura Revueltas. Rosaura’s costar, Juan Chacón, played the president of the local 890 of the UMMSW, in the role of Esperanza’s husband, Ramon. And the International’s representative, Clinton Jencks, played the role of Frank Barns. Although the film makers made plans of hiring Biberman’s wife, Gale Sondergaard, and a non-hispanic male actor to play the main characters, they realized they were giving into the stereotype that hispanics were “incapable of portraying leads.” This led to filmmakers using real miners, people who were part of the actual UMMSW and their families, to play roles in the film in order to portray the real issues they were actually living in. The movie depicts the constant inequality the hispanic workers were experiencing compared to the Anglo workers.2

The movie follows Esperanza’s narrative and her perspective, which illuminates the female hispanic narrative more generally. In the movie, miners deal with legal trouble that make them unable to strike; however, hispanic women take on the roles of the men and lead the strike. The rise to power allowed women to have their own voice in the strike and to defy social norms.3 Due to the topics of racial inequality, feminism, and labor rights, Salt of the Earth was not well received in the United States. In fact, the film saw a lot of legal challenges and violent backlash. These years of the McCarthy era caused many to see the film as glorifying communism, because of its themes of racial inequality and feminism. Not only did the American people not like it, due to their own personal biases and political opinions, they particularly did not like the way America was depicted in the movie. However, the film was well received in different countries. Despite going through a difficult and dangerous process, the resilience of the filmmakers, producers, and actors allowed the incredible film Salt of the Earth to be produced. Even though the movie was far from popular in the time that it was made, it ended up being one of the pinnacle events that inspired the Chicano movement of the 1960s.

In the 1940s, increasing immigration from Mexico sparked a debate over illegal immigration and need for deportation. The result of new incoming Mexican immigrants caused an increase in xenophobic reactions towards Mexican Americans. In the 1940s, the increasing numbers of Mexican and hispanic immigrants caused many white Americans to be threatened by their increased presence. Many were against unrestricted immigration, because they saw Mexicans as competition for jobs, and welfare agencies saw them as “costly.” Many white American citizens saw immigration as unacceptable, due to their own racist ideologies. When their racism was put into action, it resulted in Mexicans having low socioeconomic status and little political and civil power in most regions. This racism and distain towards hispanic immigrants led to the inequalities portrayed in Salt of the Earth. The majority of miners and labor workers were Mexican and the rest were non-hispanic whites.4 Unequal pay and safety concerns were prevalent in the mining industry. Many Anglo workers were received higher pay than hispanic workers. Anglo workers also had the luxury of working in pairs to bolster their safety, whereas hispanic workers were forced to work alone, thus putting them in more danger than white labor workers.5 Unfortunately, the inequality did not stop there. Companies provided houses for Anglo workers, unlike the hispanic workers, who were provided with shacks to live in. Thus, both living conditions and working conditions were significantly different. Workers who spoke Spanish were put to work as “helpers” to “skilled” Anglo workers, who would do the same job but get paid significantly more than hispanic workers. Segregation was also implemented whereby hispanic workers used separate washrooms, and were even separated in movie theaters.6

The inequalities experienced by the hispanic labor community was the main theme in Salt of the Earth, as inequalities that the Hispanic community needed to correct. These events and issues later inspired the start of the Chicano movement. During that movement, labor unions and groups formed to advance equality for hispanic Americans and to assert their civil rights. Groups like the American GI Forum began to fight for hispanic rights, like social equality and education rights. Juan Garcia, founder of American GI Forum, talked about how the lack of good education contributed to hispanic Americans being exploited. Education is a human right, and Juan Garcia said,”Education is our freedom and freedom should be everybody’s business.”7 The civil rights movement allowed minority groups to speak up for themselves and reveal the inequalities they were facing. With the movie Salt of the Earth presenting the issues hispanic Americans were facing, it became one of the main influences of the Chicano movement, where hispanic people protested to gain their rights as American citizens for equal pay, social status, and working conditions. Not only did Salt of the Earth inspire hispanic people in general to rise up and demand their rights, the narration of Esperanza inspired hispanic women to have a voice and take action.

During the making of Salt of the Earth, the movie itself saw an extremely negative response by the American people and the government. The controversial ideas presented in the film, like racial equality and feminism, caused the public to see Salt of the Earth as a communist film. During the process of filming, California Republican Representative Donald Jackson, a member of the House Committee on Un-American Activities, accused the film of being “a new weapon for Russia” shortly after the movie was released in February 1953. Jackson claimed that the film was “deliberately designed to inflame racial hatreds.” Along with these accusations, Jackson claimed the film showed two deputy sheriffs beat a miner’s young son. Micheal Wilson defended the movie saying it was “Pro-American in the deepest sense. It….depicts honest working men and women of our country in a light most Hollywood films have ignored…..It stresses brotherhood and unity.”8 The accusation about the violence demonstrated in the movie was struck down by both Wilson and a member of the UMMSW who noted that there was no “violence against any young Mexican American boy.”9 Despite this, Jackson continued to list names of the cast, crew, and producers of the movie and accused them of having ties to the Communist party. He singled out Biberman, Wilson, Sondergaard, Jarrico, and actor Will Geer, for being communists. They were each called to testify before the committee in 1953. A member of the UMMSW also denied that the film was made “under communist auspices,” and denied that Gale Sondergaard had any involvement in the movie.

After Jackson’s allegations were shut down, Jackson did not let go of the fight against Salt of the Earth. Jackson later sent a request to the Secretary of State, Secretary of Commerce, and the Attorney General with the purpose of finding legal means to band the film for being a “propaganda film.”10 In the effort to stop film production, Rosaura Revueltas was also arrested and held without bail on February 25, 1953 for being an illegal immigrant. The president of the National Association of Actors of Mexico City, Jorge Negreta, heard of Revueltas’ arrest, leading him to threaten to bar Hollywood actors from Mexico unless they let Revueltas finish the film. The accusers claimed that Revueltas was working for “a union company not signatory to our contract.” 11Despite the efforts made by Biberman and Jarrico in order to prevent the lock up of their leading lady, Revueltas was deported and sent back to Mexico on March 6, 1953. Her last scene and voice over was taped near Mexico City.12

Along with the deportation of Revueltas, the film crew and cast saw local resistance during the time of production. Filming was met with mobs of vigilantes who pushed over cameras, played loud music on speakers, and went as far as assaulting cast and crew members. The cast and crew were also told to leave town or they would be “carried out in black boxes.”13 Jencks, the actor who played Frank Barns, was beaten and had shots fired at his car while he was at home. Floyd Bostick, a cast member on Salt of the Earth, was met with violence when his house was burned to the ground. There was also a “citizen’s parade” that was led by a car and a chant that said, “We don’t want Communism; respect the law; no violence, but let’s show them we don’t like it.” Unfortunately the film was not the only group of people experiencing backlash. On March 8, 1953, the Union hall in both Bayard and Carlsbad was burned to the ground.14 After the movie was shot, laboratories refused to process the film, which led to the editing being done in secret at many venues, including the women’s restroom in an abandoned movie theater in South Pasadena. The orchestra performing the music was never told the name of the movie they were performing for. And the chief editor suddenly quit, and it came to light that the editor was payed by the FBI in order to prevent the release of the movie.15 There is no doubt that the movie faced many obstacles during its filming and production. The resistance and violence inflicted upon the cast and crew was a clear sign that the movie represented more than just a strike. The movie demonstrated a real problem that hispanic Americans were facing during that time.

In the 1940s-1950s, Americans experienced “old fears and prejudices” of the 1919 Red Scare. After the victory of World War II in 1945, the rise of Soviet communism worried many Americans. The world saw the Soviet Union control Eastern Europe, and in 1949, Maoist communism took over China. The Cold War caused Americans to have anxiety and paranoia. President Harry S. Truman announced a new United States foreign policy known as “containment,” designed to contain the spread of communism. That influenced the revitalization of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), to investigate domestic communist threats. HUAC was also known for going after alleged communists in the film industry. The hysteria against communists brought about the passing of the Internal Security Act in 1950, which is described to have “outlawed any act that might lead to the establishment of a communist government in the USA. As part of the law, Americans suspected of communist sympathies were prohibited from holding government jobs.”16

During this same period of anti-communist hysteria, Senator Joseph McCarthy rose to power by exposing people as communists or communist sympathizers. The era became known as McCarthyism, appropriately named after the Senator who fanned the flames of that hysteria. McCarthy first became known for accusing the State Department of having over 200 active communists. These accusations scared many Americans and also gave McCarthy power, as he presented himself as the only one who could rid America of communism. Due to McCarthy’s powerful speaking skills, he played on the fear of Americans.17 As a result of the hysteria built up by McCarthy, the American people learned to believe the accusations made about communism and communists. As a result of this, accusations made about Salt of the Earth had a greater impact because of the hightened anti-communist fears.

After a long struggle to make Salt of the Earth, the movie finally premiered on March 14, 1954, at the Independent theater in Yorkville, New York, and at the Grande Theatre in New York, also a non-IATSE house. The movie was able to have some showings after the premier, but they were not without obstacles caused by outside forces. The screenings in Chicago were canceled due to protests and to certain projectionists failing to show up for work.18 And those who saw it in Los Angeles had to park far from the theater because there were rumors that the FBI was collecting license plate numbers of the people who went to see the movie.19 The film was well received overseas, compared to the US. However, the showing of the movie also came with its conflicts. In Canada the branch of the UMMSW planned to have a showing of the film, but the owners of the theater had links to the US and were told not to play it. In the attempt to avoid popular opinion and the boycott of their theater, the owner of the movie theater ended up not having a showing of Salt of the Earth. The same conflict occurred in Mexico as well. The movie was expected to bring booming business in Mexico, but the Mexican government canceled the showings due to fear of American reactions. Unlike Canada, once the movie was finally released in Mexico in October 1954, the movie was “extremely” well received by news outlets and the public. The movie won several awards and honors, including its second highest rating by the Catholic Legion of Decency. Salt of the Earth was also well received in France, where it was rewarded the International Grand Prize for best film exhibited in 1955 by Academia du Cinema de Pari.20 The movie also received awards in Prague, where it earned the grand prize at the Prague Film Festival. Revueltas also received an award for her portrayal of Esperanza. Unfortunately, Revueltas was blacklisted by the Mexican film industry after her work in the picture, but continued to act in theaters in East Berlin and Havana.21 Furthermore the movie was one of the only movies to get an official release in China between 1950 and 1979.22 The movie was well received in other countries regardless of the struggles it faced during the first showings of the movie. The film went as far as to win its own awards in other countries, demonstrating the powerful narrative it brought to the film world.

During the age of McCarthyism, many believed film was used to spread communist propaganda. The result led to many filmmakers and actors being called in to testify. The House Un-American Activities Committee came up with a list containing 500 names of communist suspects who worked in the film industry.23 Due to Biberman having worked in Moscow theaters and having co-founded the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League, and his involvement in the controversial film Salt of the Earth, Biberman became a suspect for the House Un-American Activities Committee.24 In 1950, Herbert Biberman was jailed for refusing to answer the questions of the House Un-American Activities Committee. Biberman became one of the Hollywood Ten, a group of people in the film industry who refused to answer questions about having communist ties.25 The after effects of Salt of the Earth led to accusations claiming that Biberman was a communist and communist sympathizer.

Long after the movie was released, many still believed that Salt of the Earth was an incredible work of art that influenced the Chicano movement. According to sources, a showing of Salt of the Earth led Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez, two renowned labor leaders who founded the United Farm Workers, to shout “Viva la justicia!” The story was passed down through a network of feminists, labor workers, and members of the Chicano movement. The story inspired many feminist, Latinos, historians, and history buffs. It was rediscovered in the 1960s, and was used in film schools, union halls, and women’s centers. The movie was then sustained for fifty years, 26 and was later among the first 100 films to be placed in the Library of Congress’ National Registry of culturally and historically significant motion pictures made in America in 1992.27 The film experienced a lot of backlash and hate from the people at the time it was made. And it was the resilience of the cast and crew that allowed the true Hispanic American conditions to be brought to light. The movie not only revealed the hispanic experience but also demonstrated the female narrative during that time. The movie brought to light a lot of issues seen in America. Salt of the Earth was, without a doubt, ahead of its time. Even though it faced many hardships, Salt of the Earth is an incredible film that influenced the Chicano movement and changed history.

- Sukhdev Sandhu, “Salt of the Earth: Made of Labour, by Labour, for Labour,” The Guardian, March 10, 2014, sec. Film, https://www.theguardian.com/film/2014/mar/10/salt-of-the-earth-labour-workers-blacklisted-filmmakers. ↵

- “AFI|Catalog – Salt of the Earth,” accessed February 21, 2023, https://catalog.afi.com/Catalog/moviedetails/53396. ↵

- Scott Henkel and Vanessa Fonseca, “Fearless Speech and the Discourse of Civility in Salt of the Earth,” Chiricú 1, no. 1 (2016): 21,22, https://doi.org/10.2979/chiricu.1.1.03. ↵

- Brian Gratton and Emily Klancher Merchant, “An Immigrant’s Tale: The Mexican American Southwest 1850 to 1950,” Social Science History 39, no. 4 (2015): 522, 537, 540. ↵

- Scott Henkel and Vanessa Fonseca, “Fearless Speech and the Discourse of Civility in Salt of the Earth,” Chiricú 1, no. 1 (2016): 21-22, 27, https://doi.org/10.2979/chiricu.1.1.03. ↵

- “AFI|Catalog – Salt of the Earth,” accessed February 21, 2023, https://catalog.afi.com/Catalog/moviedetails/53396. ↵

- Michelle Hall Kells, Vicente Ximenes, LBJ’s Great Society, and Mexican American Civil Rights Rhetoric (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2018), 90. ↵

- “AFI|Catalog – Salt of the Earth,” accessed February 21, 2023, https://catalog.afi.com/Catalog/moviedetails/53396. ↵

- “AFI|Catalog – Salt of the Earth,” accessed February 21, 2023, https://catalog.afi.com/Catalog/moviedetails/53396. ↵

- “AFI|Catalog – Salt of the Earth,” accessed February 21, 2023, https://catalog.afi.com/Catalog/moviedetails/53396. ↵

- “AFI|Catalog – Salt of the Earth,” accessed February 21, 2023, https://catalog.afi.com/Catalog/moviedetails/53396. ↵

- “AFI|Catalog – Salt of the Earth,” accessed February 21, 2023, https://catalog.afi.com/Catalog/moviedetails/53396. ↵

- Sukhdev Sandhu, “Salt of the Earth: Made of Labour, by Labour, for Labour,” The Guardian, March 10, 2014, sec. Film, https://www.theguardian.com/film/2014/mar/10/salt-of-the-earth-labour-workers-blacklisted-filmmakers. ↵

- “AFI|Catalog – Salt of the Earth,” accessed February 21, 2023, https://catalog.afi.com/Catalog/moviedetails/53396. ↵

- Sukhdev Sandhu, “Salt of the Earth: Made of Labour, by Labour, for Labour,” The Guardian, March 10, 2014, sec. Film, https://www.theguardian.com/film/2014/mar/10/salt-of-the-earth-labour-workers-blacklisted-filmmakers. ↵

- Hugh Jebson, “The ‘Red Scare’: Part 2: the USA in the 1950s,” Hindsight, April 2008, 4+. Gale General OneFile (accessed April 21, 2023). ↵

- Hugh Jebson, “The ‘Red Scare’: Part 2: the USA in the 1950s,” Hindsight, April 2008, 4+. Gale General OneFile (accessed April 21, 2023). ↵

- “AFI|Catalog – Salt of the Earth,” accessed February 21, 2023, https://catalog.afi.com/Catalog/moviedetails/53396. ↵

- “Why Suppress Salt of the Earth,” accessed February 21, 2023, https://pages.mtu.edu/~smbosche/courses/read/2. ↵

- James J. Lorence, The Suppression of Salt of the Earth : How Hollywood, Big Labor, and Politicians Blacklisted a Movie in Cold War America (Albuquerque, N.M.: University of New Mexico Press, 1999), 150, 152. ↵

- “AFI|Catalog – Salt of the Earth,” accessed February 21, 2023, https://catalog.afi.com/Catalog/moviedetails/53396. ↵

- Sukhdev Sandhu, “Salt of the Earth: Made of Labour, by Labour, for Labour,” The Guardian, March 10, 2014, sec. Film, https://www.theguardian.com/film/2014/mar/10/salt-of-the-earth-labour-workers-blacklisted-filmmakers. ↵

- Hugh Jebson, “The ‘Red Scare’: Part 2: the USA in the 1950s.” Hindsight, April 2008, 4+. Gale General OneFile (accessed April 21, 2023). https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A177828950/ITOF?u=txshracd2556&sid=bookmark-ITOF&xid=ed3da0e0. ↵

- Sukhdev Sandhu, “Salt of the Earth: Made of Labour, by Labour, for Labour,” The Guardian, March 10, 2014, sec. Film, https://www.theguardian.com/film/2014/mar/10/salt-of-the-earth-labour-workers-blacklisted-filmmakers. ↵

- “STARZ! Cinema Presents 1953 Banned Film SALT OF THE EARTH, Landmark Film To Be Shown In Conjunction With ONE OF THE HOLLYWOOD TENSTARZ! Pictures Exclusive World Premiere Drama About Blacklisted Herbert Biberman And The Making Of His Historic Film – Document – Gale OneFile: Business,” accessed March 26, 2023. ↵

- Lee Hockstader, “‘Salt of the Earth’ Is Back from the Blacklist,” Los Angeles Times, March 4, 2003, https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2003-mar-04-et-hock4-story.html. ↵

- “STARZ! Cinema Presents 1953 Banned Film SALT OF THE EARTH, Landmark Film To Be Shown In Conjunction With ONE OF THE HOLLYWOOD TENSTARZ! Pictures Exclusive World Premiere Drama About Blacklisted Herbert Biberman And The Making Of His Historic Film – Document – Gale OneFile: Business,” accessed March 26, 2023. ↵

4 comments

Mariana Chamorro

Danielle, your publication on is a compelling exploration of a pivotal film in American history. I admire how you delve into the movie’s significance in sparking the Chicano movement and shedding light on the struggles faced by Hispanic Americans. Your analysis of the social and political context surrounding the film’s production adds depth to its impact.

Linda Aguilar

I enjoyed reading the article “The Untold Story of Salt of the Earth”

The movie was ahead of its time. Its themes of racial inequality, feminism, labor rights, and inequality of Hispanic workers were controversial. This article is well-written and gives a perspective on the civil rights movement in the 60’s. This film was used by the Chicano movement for inspiration and later adopted by the Library of Congress. Congratulations on the nomination Danielle!

Esteban Serrano

It feels really strange to me personally how just 60-70 years ago, which is not a lot of time, the United States was very ignorant towards minorities and their ideologies. I am very motivated now to go find this movie, watch it, and interpret it in a different way.

Very informative and compelling article, Danielle! Congrats on your nomination!

Gaitan Martinez

Very informative article, and it has me convinced to watch the Salt of The Earth documentary. I love documentaries, and I recently watched the RBG documentary. I’m very familiar with worker strikes because work wasn’t always fair and safe. I remember writing a paper about the triangle shirtwaist fire because it was a preventable fire that killed over 100 people in under ten minutes. So if its about wrong workers getting justice, then I’ll watch it.