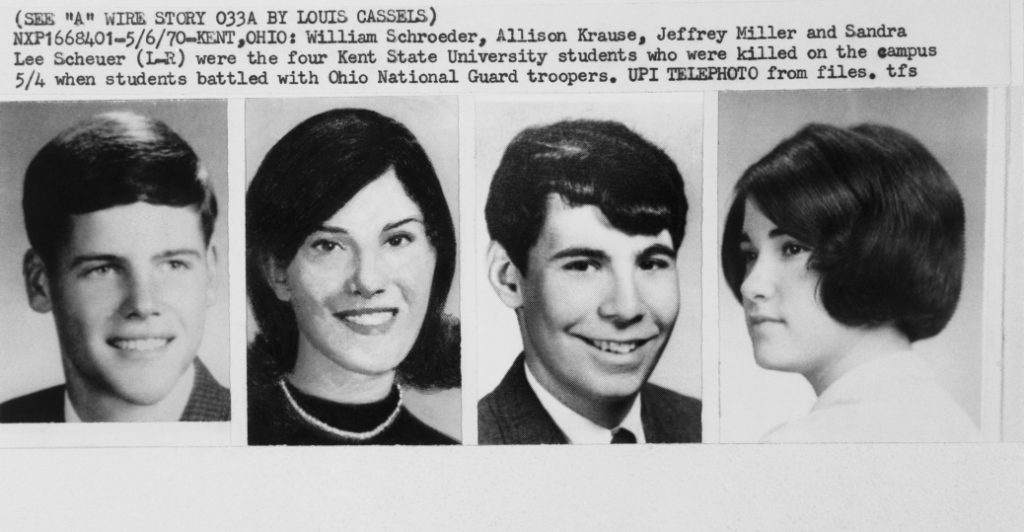

Alison Krause, 19; William Schroeder, 19; Jeffrey Miller, 20; and Sandra Scheuer, 20. These four individuals come from different backgrounds, but they share the same piercing story. What is it that binds them together? Could it be their age? Could it be that they each attended the same university? Or maybe they shared the last day of their life together?

During the latter half of 1960s, anti-war rallies were common in the United States; most of them were led by college activists. A reason for this was their opposition to the Vietnam War, and particularly to the draft lottery of 1969, which targeted young men between the ages of nineteen and twenty-five. Students united to fight for one common cause and that was to stay out of the Vietnam War. Many individuals were angered by President Nixon’s decision to continue the United States’ involvement in the Vietnam War, which led to a great number of student protests and anti-war rallies nationwide. A variety of protest took place in Kent, Ohio during a four-day event in 1970. There was a buildup of anger, violence, and social upheaval, until finally the ticking bomb detonated and four individuals lost their lives. On May 4, 1970, the life they once had had left their bodies by the penetration of a single bullet. This tragedy divided the nation even more. But what exactly led the Kent State University shooting?

During the 1968 presidential election, Republican nominee Richard Nixon won the presidency. One of his main campaign promises was that he would end the Vietnam War. Nixon started to keep his promise, as the United States’ troop commitment stopped increasing; but on April 28, 1970, he broke his promise by sending U.S. military forces to invade Cambodia. This was known as the Cambodia Incursion; the purpose of the invasion was to attack the Viet Cong. The Viet Cong were a group of North Vietnamese communists who had been seizing the Cambodian territory as a sanctuary.1 The news of the invasion was announced to the American public on April 30, when the president addressed his plan through television and the radio. The news of the invasion did not sit well with the public, and many became infuriated by the news. Public opinion was divided by those who agreed with the president and those who wanted to get out of the Vietnam War.

The following day, on May 1, 1970, protests begin at Kent State University. The rally was held on the school’s commons by a group known as the World History Opposed to Racism and Exploitation (WHORE). The commons was a field located at the center of Kent State, which was popular for rallies and campus meetings among the students. WHORE, along with the New University Conference, sponsored the anti-war rally. The event transpiring at this time was not violent in any way, but was rather calm. About 500 demonstrators attended to protests the Cambodian Incursion. Nonetheless, a group of “rally leaders buried a copy of the United States Constitution, declaring that it had been ‘murdered’ when troops had been sent into Cambodia without a declaration of war or consultation with Congress.”2 As the rally was coming to an end, a new protest was planned for May 4 at the university’s commons.

However, the May 1 protests was not completely over yet, as many students began assembling in downtown Kent at the North Water Street Bar, which consisted of six bars. It was a well-known place for students because the “sale of 3.2 beer to person 18 or older, and of liquor to 21 year olds” was legal in Kent.3 Protesting started off rather peaceful; then things turned violent when demonstrators started to taunt police officers and began throwing beer bottles at their vehicles. The mayor of Kent, Leroy M. Satrom, was made aware of what was happening in the late hours, so he ordered all bars to be closed. This only angered the mob more. Protesters vandalized businesses, breaking windows and even stealing store goods. A discussion of Cambodia turned into a riot when protesters then began igniting a bonfire on the road, making it difficult for vehicles to get around.4 Around 2:00 AM deputies were able to clear the crowd around downtown Kent by using tear gas and moving most of them back to Kent State campus.5

The second wave of protests in Kent started to become excessively violent; rallies turned into riots and threats persisted across the city. On May 2, Mayor Leroy asked Ohio governor James Rhodes for assistance in sending the Ohio National Guard to Kent. The National Guard was supposed to arrive at Kent during the afternoon but did not arrive until 10:00 PM. This was because the Ohio National Guard was stationed in Northeast Ohio. However, a civil emergency was declared for Kent and a curfew was implemented from 8:00 PM until 6:00 AM.6 In Kent State the supposed curfew was ignored, as damage was occurring when a group of individuals burned down the Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) building. “A large crowd of over five hundred protesters gathered around the burning building to cheer; the crowd slashed the firefighters’ hoses, temporarily preventing them from extinguishing the blaze.”7 The demonstrators fought against the guardsmen and once again tear gas was used to disperse the crowd. It was the second day of protest in Kent, Ohio, and rallies were becoming increasingly violent as the hours went by. The city was becoming a war zone between anti-war protesters and the Ohio National Guard.

Richard Nixon was sworn in as the 37th president of the United States of America in 1969. Richard Nixon was a prominent and successful president in foreign affairs. He was “something of a closet intellectual who read widely and thought deeply about history and diplomacy.8 One of his promises during his first term as president was that he would be the president to end the Vietnam War once and for all; he would “relieve the anti-war and anti-draft pressure at home” by adopting Vietnamization. But regardless of his approach to end the Vietnam War, he increased turmoil by secretly bombing Cambodia, which would decrease communist control, but it only made matters worse. In a way, he believed, he was far greater and more powerful than Congress: “Nixon wanted to demonstrate to his ‘enemies’ that he could operate a secret diplomacy just as they did, and that he would not be pushed around by anti-war mobs in the streets, Congress, and his special enemy, the media.” With his invasion in Cambodia, he created the “greatest violence and instability in history on American campuses, including the killing of four students by National Guardsmen at Kent State University in May 1970 and strong opposition in the Democratic-controlled Congress.”9 So, now did the president have blood on his hands because he went against telling Congress and the American people about the Cambodia invasion? Not only did he cause great distress within the nation, but during his second term as president he was guilty of covering up the break in to the Democratic National Committee headquarters, which became the scandal that brought down his presidency, known as the Watergate Scandal. Richard Nixon was forced to resign as the thirty-eight president of the United States.

The Vietnam War caused great distress to American soldiers and American civilians seeing the destruction of the war. Many wanted to stay out of Vietnam, but the President had other ideas. Vietnamization was the term first used by the Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird to describe Richard Nixon’s plan for the Vietnam War. “Vietnamization entailed the progressive withdrawal of U.S. forces from South Vietnam combined with efforts to enhance the training and modernization of all South Vietnamese military forces to enable the government of South Vietnam to assume greater responsibility for the conduct of the war.”10 This meant that the United States was slowly withdrawing troops from the war and giving complete responsibility and control to the Vietnamese. By 1970, 150,000 American forces had been withdrawn from Vietnam. However, although this might have worked in many aspects, “Nixon’s plan to Vietnamize the war actually increased the number of American casualties. The American public was traumatized by media coverage of the death and destruction.”11

The protests continued at Kent State University, it was now the third day in a row that students and anti-war activists were protesting the United States involvement in the Vietnam War. Around Kent State University, guardsmen surrounded the campus. “Nearly 1,000 Ohio National Guardsmen occupied the campus, making it appear like a military war zone.”12 Governor Rhode was irritated with the events that had been transpiring, so, on Sunday morning he held a press conference, where he voiced a harsh statement against the protesters. He stated that these protests were the “most vicious form of campus-orientated violence” he had witnessed and that he would provide everything in his power to have all forms of authority regulate Kent, Ohio; he continued by calling them the worst type of people that harbor America. He said, “We are going to eradicate the problem…we are not going to treat the symptoms.”13

However, this did not stop the rallies; it only worsened an already violent atmosphere. Throughout the day, confrontations between the people and the guards continued. “Rocks, tear gas, and arrests characterized a tense campus.”14 Following the press conference, 12,000 leaflets were distributed throughout the public. The leaflets listed “curfew hours; said the governor through the National Guard had assumed legal control of the campus; stated that all outdoor demonstrations and rallies, peaceful or otherwise, were prohibited by the state of emergency; and said that the Guard was empowered to make arrests.”15 With these leaflets and the governor’s press conference, many believed that the worse was finally over, but they were wrong. The worst was still on its way. School property, such as windows, were destroyed and quite a few arrests were made that night. The guardsmen were becoming highly outraged because of the protesters unwillingness to cooperate; therefore, a curfew was put in place.16 The following day, May 4, the last day of the violent protests, was about to bring an unexpected end.

“Student movements have the potential to generate major social change in the context of underlying economic, demographic, and other social forces. This makes student movements a strategic factor in assessing the nature of some consequential social change developments in society.”17 The United States had experienced many types of social change. One such movement was triggered by the 1954 Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education; another was triggered by the 1960 Greensboro sit-ins, and another by the 1964 Freedom Summer, all civil rights movements for African Americans for the goal of equality and respectability. However, many of the civil rights movements all had one thing in common, and that was to bring about change. The Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee, the Red Power Movement, the Chicano Movement, and the Anti-War Movement were some of the many movements that fought for change; all involving mass protests demanding equality, fighting against racism and police brutality, and fighting for improved labor conditions. These movements later inspired other movements for change, such as the environmentalism of the 1970s, women’s rights and the gay rights movements to name the most prevalent. There were thousands of student protests in the United States in the late 60s and early 70s, many going unnoticed, others gaining the attention of the nation. Whatever the cause, student protests “in their manifestos and calls for nonviolent cultural revolution, democratic reform, unity with the oppressed, or violent revolution, students worldwide called into question the system, that is, the entire ordering of modern society. The protests were often as much a celebration of youth as efforts directed at sharply defined goals.”18

The freedom to shift and bring attention to a cause by organizing student protests, strikes, or boycotting has become familiar in the United States; as many students began to realize their potential for bringing change to the nation, and all they had to do was speak up and become a part of something greater. An example of this is the most recent school shooting that occurred in Parkland, Florida in 2018. High School students around the nation participated in a school walkout for seventeen minutes to honor the seventeen lives lost at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School. The attention these students received was taken to bring change to America. Their purpose was not to allow themselves to become just another statistic; they didn’t want this to become just another mass shooting in America, where people would soon forget and move on. They sought to use this opportunity for the young people to spark a change that would make a difference. This led students, activists, believers, parents, teachers, supporters to Washington, D.C. to plea for stricter gun laws. This movement has become known as the March for Our Lives, and its objective is to create regulations for gun owners; not take away their protection, but have better universal background checks and raise the age of gun purchases to 21 rather than 18. Their goal is to stop other students from experiencing the horror that they had to live through on February 14, 2018; and to cease another parents suffering from losing their loved ones to yet another shooting massacre.

On the last day of the anti-war rallies, students were prohibited by University officials from protesting at the school’s Commons. However, by noon there was already a large crowd of protesters. “About 500 core demonstrators were gathered around the Victory Bell at one end of the Commons, another 1,000 people were ‘cheerleaders’ supporting the active demonstrators, and an additional 1,500 people were spectators standing around the perimeter of the Commons. Across the Commons at the burned-out ROTC building stood about 100 Ohio National Guardsmen carrying lethal M-1 military rifles.”19 The night before, the Ohio National Guard had had at least three hours of sleep. Therefore, many were hoping for the protests to not take place. The rally, however, was quite peaceful at the beginning. It is not clear if this rally was to protest the National Guard stationed at the university or the Cambodian invasion. Either way, there was a record attendance. Harold E. Rice was a Kent State officer who ordered students to move away from the Commons. Students responded by using profanity against the guards, taunting them with “Pigs off campus,” and started to throw rocks at them. Guards begin throwing tear gas canisters at the crowds, causing many to leave the premises; but others threw the canisters back to the guards. “Some among the crowd came to regard the situation as a game—’a tennis match’ one called it—and cheered each exchange of tear gas canisters.” Guardsmen begin advancing towards the students to clear the Commons. As the students moved away, they headed towards Blanket Hill on the university grounds. The Guardsmen headed straight towards an enclosed practice field. The guards tried to make their way back to Blanket Hill, but some felt fearful for their lives.20 Although there were numerous aggressive individuals, many were only bystanders. It is not clear why one guardsman fired his pistol, but soon other troops begin to fire into the air, on the ground, and into the crowd. In a matter of thirteen seconds, between 61 and 67 shots were fired. 21 Four students were killed and nine were injured. Two were protesters and the other two where bystanders.

Allison Krause, 19, was killed by a bullet that went through her left upper arm and into her left side. She was protesting and was 110 yards away when she was killed. William Schroeder, 19, was killed by a bullet that went through his left back and seventh rib. He was a bystander and was 130 yards away when he was killed. Jeffrey Miller, 20, was killed by a bullet in the mouth. He was protesting and was the closet to the guards, 85 to 90 yards away when he was killed. Sandra Scheuer, 20, was killed by a bullet through the left side of her neck. She was a bystander and was 130 yards away when she was killed.22 Many believe it was the fault of both parties; the President’s Commission on Campus Unrest reported: “Violence by students on or off the campus can never be justified by any grievance, philosophy, or political idea. There can be no sanctuary or immunity from prosecution on the campus. Criminal acts by students must be treated as such wherever they occur and whatever their purpose. Those who wrought havoc on the town of Kent, those who burned the ROTC building, those who attacked and stoned National Guardsmen, and all those who urged them on and applauded their deeds share the responsibility for the deaths and injuries of May 4.”23 The tragedy that happened on May 4, 1970 was an awakening call to America; what are we doing when our children are being shot? Although, the Kent State Shooting was violent at times, no individual deserved to be killed for protesting or for being a bystander to the protest. After this tragedy, those in favor of the war fell suddenly silent, while America mourned.

Shortly after the event, the tragic day was further memorialized in the famous song by the rock group Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young: “Ohio.” This is that song:

- Jerry Lewis M and Thomas R. Hensley, “The May 4 Shootings at Kent State University: The Search for Historical Accuracy,”Kent State University (1998). https://www.kent.edu/may-4-historical-accuracy. ↵

- “The Report of the President’s Commission on Campus Unrest, (U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C, 1970), 240. ↵

- “The Report of the President’s Commission on Campus Unrest” (U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C, 1970), 241. ↵

- Government, Politics, and Protest: Essential Primary Sources, 2006, s.v. “Kent State Shootings,” by John Filo. ↵

- “The Report of the President’s Commission on Campus Unrest, (U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C, 1970), 242. ↵

- “The Report of the President’s Commission on Campus Unrest, (U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C, 1970), 244. ↵

- Government, Politics, and Protest: Essential Primary Sources, 2006, s.v. “Kent State Shootings,” by John Filo. ↵

- The Scribner Encyclopedia of American Lives, Thematic Series: The 1960s, 2003, s.v. “Nixon, Richard Milhous,” by Melvin Small. ↵

- The Scribner Encylopedia of American Lives, Thematic Series: The 1960s, 2003, s.v. “Nixon, Richard Milhous,” by Melvin Small. ↵

- Dictionary of American History, 2003, s.v. “Vietnamization,” by Vincent H. Demma. ↵

- Encylopedia of Modern Asia, 2002, s.v. “Vietnam War,” by Richard C. Kagan. ↵

- Jerry M Lewis and Thomas R Hensley, “The May 4 Shootings at Kent State University: The Search for Historical Accuracy,” Kent State University, (1998). https://www.kent.edu/may-4-historical-accuracy. ↵

- “The Report of the President’s Commission on Campus Unrest, (U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 1970), 254. ↵

- Jerry M Lewis and Thomas R Hensley, “The May 4 Shootings at Kent State University: The Search for Historical Accuracy,” Kent State University, (1998). https://www.kent.edu/may-4-historical-accuracy. ↵

- “The Report of the President’s Commission on Campus Unrest,” (U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 1970), 255. ↵

- “The Report of the President’s Commission on Campus Unrest, (U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 1970), 258-259. ↵

- Encyclopedia of Sociology, 2001, s.v. “Student Movements,” by Leonard Gordon. ↵

- World History Encyclopedia, 2011, s.v. “Student Protest Movements, 1945-1960,” by Alfred J. Andrea and Carolyn Neel. ↵

- Jerry M Lewis and Thomas R Hensley, “The May 4 Shootings at Kent State University: The Search for Historical Accuracy,” Kent State University, (1998). https://www.kent.edu/may-4-historical-accuracy. ↵

- “The Report of the President’s Commission on Campus Unrest, (U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 1970), 259, 260, 263, 267, 268, 274. ↵

- Jerry M Lewis and Thomas R Hensley, “The May 4 Shootings at Kent State University: The Search for Historical Accuracy,” Kent State University, (1998). https://www.kent.edu/may-4-historical-accuracy. ↵

- “The Report of the President’s Commission on Campus Unrest, (U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 1970), 273. ↵

- “The Report of the President’s Commission on Campus Unrest, (U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 1970), 287. ↵

67 comments

Rahni Hingoranee

The story of the Kent State University shooting is heartbreaking in the lives that were lost. The structure of this article is especially easy to follow and outlines all the important details. The Kent State University shooting was one that changed the perspective of protest and police involvement in it. The students were practicing their peaceful protest and did not by any means deserve to lose their lives. Overall, it is a well-written article.

Gabriella Urrutia

This article was very well written. It did a good job at telling the story of what happened to them and also what was going on politically at the time. I had never heard of this incident before so it did a good job at providing the details of what happened. It is sad to hear that two of the people that died weren’t even part of the protest, they were just bystanders.

Amanda Uribe

What happened to the students of Kent University was not okay. It is so sad to think that four young people were killed for fighting against a terrible war. It is sad to think that not even all of the four were protesting. They were just bystanding and they were killed by our own. We have a right to assemble in this country and they were stripped of their rights.

Jacob Silva

This was a really great and interesting read for me. I remember in AP US History briefly going over this event and how it correlates with the Vietnam War, so its always great to learn more about topics I only have surface level knowledge on. Additionally, this article gives me a good idea on what a journalistic explanatory article is supposed to look like.

Jake Mares

Great article! I enjoyed seeing the transition between what was occurring at Kent State and what was happening on the broader spectrum of the war. The loss of these people is tragic considering political promises had not been kept. Protests with this kind of backing seem to always become violent, but not all participants are the ones throwing rocks and beer bottles. This is a prime example of tragedies that can happen among protesters even when two of them were just bystanders.

Sebastian Azcui

I really liked the article structure and how you managed to get through all that research. You were excellent writing a Journalistic Explanatory Article. The idea that I can keep reading and the idea that your story just goes on is what makes it good. It was pretty concise and easy to understand.

John Cadena

In his book, Jack Hart recounts a meeting he had with Oregonian reporter Rich Read. At this meeting, Jack reminded rich he did not need to follow a person when writing a narrative. In writing, it was most important for the story to “keep moving”. In reading this piece, I was remined of this concept. As shown here, fitting a well-placed idea into the seat of the protagonist, just as easily can capture an audience well enough to keep a narrative moving. In this story, I found it easier to except this un-natural form of story-telling through the authors quick change between narrative and digression. Unlike other stories I have come across, this author achieved this rapid movement by constructing for the reader short and concise paragraphs. This limited the reader to just what needed to be known before moving on to a continuation of another detailed paragraph.

Edgar Velazquez Reynald

I think this is a very concise article that is able to shed light on a tragic event and what led up to it. I’m glad you were able to use the photograph with Mary Ann. That is a very powerful image, one that sticks with you forever. What I especially like about your piece is how you make it relevant for college students of today. Hopefully, people can see parallels with situations going on today.

Danielle A. Garza

The article kept a very respectful tone throughout and I feel like that’s important when someone is talking about an event like this. I enjoyed your article in really getting the description of the days before to tell a story. I do wish I could have known what happened after, that being any type of reforms by government. I would have also like if there were more big picture ideas. Your article was very emotional and insightful.

Scott Sleeter

This is a very informative piece of writing. I like how both the event is covered and the lead up to is handled. Excellent use of explanatory narrative to weave the story together and keep the read on top of all the facts. It was easy to understand how this tragedy happened, and how it could have been avoided. It is sad that the biggest turning point in the Vietnam war was a battle in Kent, Ohio.