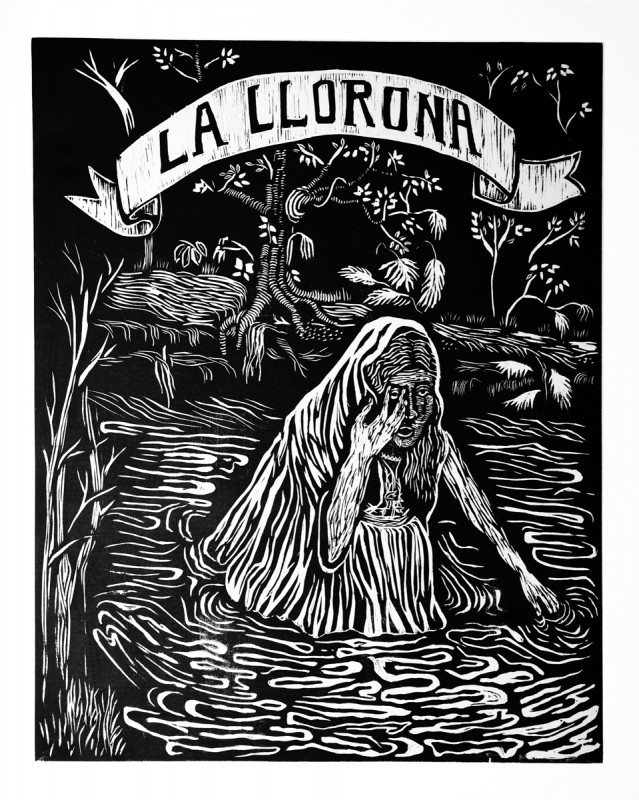

There she is, hair black as night with a dress on as white as snow, but for some reason you can’t get a good view of her face. Then, all of sudden, she’s in yours, screaming at the top of her lungs. This is not your typical girl, and although she may sound like one, she is much worse. What you just witnessed is a mother grieving for her children. Some might question her parental instincts, but she only killed them for love, and let’s be honest, love makes you do some crazy things. If you are wondering who I am talking about, the woman I am referring to is La Llorona, who also answers to the name weeping woman.

The story is about a beautiful lady who fell in love with a man. They got married and had children, but sadly the husband died and left the lady to raise their children alone. Even with the struggles of raising her children alone, she found love again with another man. Everything was going great between them, until he found out that she has children. Furious with her, he left her for another woman. Anger and despair filled her heart and her mind, so she blamed her children for ruining what she wanted the most. She believed that if she could get rid of the children, he would come back to her. So she took her children to the river, where she drowned them. But shortly after she realized what she had done, she became horrified at herself. With a broken heart, forever after she then went on in life, mourning for the loss of her children. After her death, it is said that she lures people away to kill them in the hope of finding her lost children.1

This story dates back for centuries, starting before the Spanish Conquest. During that time period, the story is that an Aztec emperor had heard a woman’s cries and asked a nearby priest what it meant. The priest replied, saying that the cries were from the goddess Cihuacoatl, and her cries were one of the eight omens of doom. These omens began manifesting during the ten years before the arrival of Cortes in 1519. Cihuacoatl is the Aztec goddess who supposedly steals children away from their mothers and fathers, then later on sacrifices them.2

In other related stories of La Llorona, the woman isn’t known as La Llorona, but rather as La Malinche, the Indian mistress of Cortes. In this version, she doesn’t weep because of the loss of her children, but instead weeps because she betrayed her people to the conquerors.3 Cortes was the Spanish conquistador and Malinche was sold to him as a slave, but over time she was willing to help him on several adventures, but by doing this, she turned against her people. Although no known children were killed, she does appear to have had children with Cortes. This is where the origins of the legend gets confused on which culture actually created La Llorona. There are rumors saying that the Spanish may have gotten the origins confused with one of their own native legends.4 Regardless of where the story was first heard, the documentation of La Llorona appeared around 1550.5 Over time, the myth of La Llorona has been adapted to different customs and traditions, but each adaptation continues to recount five stable elements: a woman, a white dress, weeping for lost children, wandering, and water.

In other versions of the story, Llorona is simply a woman who drowns her children. English-language versions of the story simply call the woman the weeping woman, with her white dress symbolizing her link to the spiritual world as a ghost. In most of her stories, children do die; therefore, she weeps for them regardless of how they may die. While wandering and water are separate story elements, they go hand in hand in each adaptation. The Weeping Woman will always be wandering to find her drowned children, no matter where the story is told. This is why parents in the American south-west ( in California, Arizona, Colorado, Texas, and Mexico) warn children not to stray away, be naughty, or go out after dark, because they believe if the Weeping Woman is out there wandering, she could find you.6 Not only does she wander everywhere, but she typically will wander near bodies of water. This creates yet another warning that parents impart to their children, believing that water is dangerous and unpredictable. To prevent children from going near water without an adult, they tell their children the tale of La Llorona.

But it’s not just children that she goes after, but rather everyone. Typically, it’s more common for her to go after men than women, because it was a man who drove her to kill in the first place. So she uses her broken heart to get revenge on men because of how betrayed she feels.7 She uses her weeping to lure men to her, then kills them shortly afterwards. Since it is more common for males to be lured away, there are lessons for boys, namely, that the tale suggests to boys that women are temptresses of malevolent sexuality that can cause them to lose their souls as well as control of their bodies.8 While women aren’t primarily targeted, La Llorona can also teach young girls lessons as well, namely, that girls should be careful not to fall for a young man who may have wealth and nice clothes, but who is too far above them to consider marriage.9 Although it may seem unfair to women, overall the tale is meant to protect young ones from disobedience and to guide them in proper behavior. Since the story revolves around a woman, it is common for mothers and grandmothers to tell the Weeping Woman tale. Since the story is more typically shared by women rather than men, women used this to create an adaption in La Lloronas tale. Most females believe that La Llorona is a fragile woman, giving the impression that females are victims. So by evolving her story, they can adapt La Llorona to seem strong and powerful.

In Seguin, Texas you will find a place called Woman Hollering Creek, which crosses Interstate 10 near San Antonio, Texas. It is here where the story changes from one depicting a grieving mother to a survivor. In this version, the woman is a young bride in a white dress. But instead of being left behind by a man, she is beaten and has a miscarriage. The creek goes along her house, so she wanders along it while her husband is away at work. Later on in her life she gives birth, and it was at that point where she conjures up images of La Llorona.10 In this version, it still manages to have all the key elements of La Lloronas story. The white dress because she is a female bride, the weeping for children because she had a miscarriage, the Woman Hollering Creek being her source of water while wandering around it. However, instead of weeping and longing for children for eternity, she uses her voice in other ways. The Woman Hollering Creek story has her gaining her voice as a sign of rejection from domestic abuse. Although it may be completely different from most known stories, this one has became popular in the female world. With La Lloronas’ legend, women experience a sense of feeling trapped because of their lack of control. But in the Woman Hollering Creek version, instead of luring people to their death or seeking vengeance for a violent husband, the woman simply lives her life. She doesn’t cave in to a dangerous mind, but rather show that she’s stronger than that.

Adaptations of these stories will continue to change over time, sometimes making her a victim, sometimes a murderer, and sometimes a survivor. La Llorona may be an old myth, but her lessons and her stories continue. Keep this in mind the next time you misbehave, or wander alone, or go near water, because you never know when you might stumble upon a beautiful lady searching for lost children.

- Celebrating Latino Folklore: An Encyclopedia of Cultural Traditions, 2012, s.v. “La Llorona (The Wailing Woman),” by Leigh Johnson, 657. ↵

- Ana Maria Carbonell, “From Llorona to Gritona: Coatlicue in Feminist Tales by Viramontes and Cisneros,” MELUS 24, no. 2 (1999): 55. ↵

- Betty Leddy, “La Llorona Again,” Western Folklore 9, no. 4 (1950): 365. ↵

- Celebrating Latino Folklore: An Encyclopedia of Cultural Traditions, 2012, s.v. “La Llorona (The Wailing Woman),” by Leigh Johnson. ↵

- Celebrating Latino Folklore: An Encyclopedia of Cultural Traditions, 2012, s.v. “La Llorona (The Wailing Woman),” by Leigh Johnson. ↵

- Bacil F. Kirtley, “‘La Llorona’ and Related Themes,” Western Folklore 19, no. 3 (1960): 155. ↵

- Bacil F. Kirtley, “‘La Llorona’ and Related Themes,” Western Folklore 19, no. 3 (1960): 156. ↵

- Celebrating Latino Folklore: An Encyclopedia of Cultural Traditions, 2012, s.v. “La Llorona (The Wailing Woman),” by Leigh Johnson. ↵

- Celebrating Latino Folklore: An Encyclopedia of Cultural Traditions, 2012, s.v. “La Llorona (The Wailing Woman),” by Leigh Johnson. ↵

- Celebrating Latino Folklore: An Encyclopedia of Cultural Traditions, 2012, s.v. “La Llorona (The Wailing Woman),” by Leigh Johnson. ↵

131 comments

Kayla Lopez

I remember my grandmother always telling me this story to ensure that I behaved and always followed the rules. I did not know that there were this many adaptations to this story and it is interesting how La LLorona can go from a murderer in one adaptation, a survivor in another, and a victim in others. This article really caught my attention due to the fact that I have grown up with a story of La LLorona.

Hanadi Sonouper

This myth is truly a classic, even back in my days as a young child, I remember the countless renditions of this stories brought on by classmates and family members. Of course, everyone has their own interpretations, but the interesting fact about the story is that I did not realize that it actually traces back to the Aztecs. It is truly an ancient story that has been passed down through generations and generations, the author did a great job at highlighting the story itself, the history, and current day events that fall under the same genre. Nonetheless, it was always a great listening tool to captivate someones attention!

Natalie Childs

Before now, I honestly knew very little about La Llorona. I had heard the name a little from friends, but never really knew much about her. With that said, the author did an amazing job of not only telling the tale of the weeping woman for people who knew nothing of her, she gave back story and other origins and versions of the tale. This made for an incredibly well written tale that really depicted the myth in a great way.

Edgar Ramon

The all time Mexican classic, ‘La Llorona’ was probably in every child’s nightmares at least once. It was just one of those creepy stories that your parents or an uncle told you for probably no good reason, but to traumatize you. The funny thing about la llorona, is that just about every Mexican kid believes that ‘La Llorona’ appeared in their own town, when it’s very unclear where this woman, if ever she was real killed her children.

Julian Aguero

I remember hearing this story by my friend’s parents growing up. They told us this story so we wouldn’t leave the house during sleep overs. It acutely did the opposite and sometimes we would leave the house in search for a scare. It is interesting how many different versions of the story there are. Growing up I remember hearing both stories but never really new the origin of the myths. I believe that all myths relate some universal truths. Great article and very interesting background.

Alexandra Lopez

La Llorona was always a scary story my siblings and me would tell each other at night to scare us. I had known about the story version mostly everyone knows; she killed her children because a man didn’t want them. I hadn’t known that the myth of La Llorona dates back so many decades. Reading that this myth was tweaked from an Aztec myth is baffling. I also didn’t know about the other myths and story versions and it’s quite amazing to know those versions too. The stories are unique and tailored to the certain culture but highlight similar characteristics of one another.

Jason Garcia

The story of La Llorona was used to keep my brothers and I in check when we were misbehaving. It scared us to death. I had always grown up with the legend but I never actually heard the story behind it until now. What really peaks my interest in this article is the fact that the La Llorona mythos isn’t just a San Antonio thing! The connections to Native American culture are mindblowing and, for me at least I can see how legends like “Cihuacoatl” can be passed through cultures. A little tweaking and BAM another set of people believe and embrace it.

Yahaira Martinez

This story is the only way my mom got me to listen to her when i was little, she would say the llorona would come and take me if i didn’t and of course i would run into the house crying and doing everything she would tell me to do. This article not only took me back to my childhood but made me realize that it is a story that will continue to be passed on from generation to generation and how each generation tells the story differently to portray the llorona as the victim or the murdered. nonetheless this folktale will be a common name in my household if my children misbehave.

Benjamin Arreguin

Growing up with two very religious and supersticious grandmothers, both of whom lived across from a cemetary, this was the story they used to make me behave. I did not know about the version of La Llorona with the bride, but the story about the grieving mother I am very familiar with. I didn’t realize how old the stories were and where they truly originated, so this insight is very interesting and still pretty effective on kids and grown college students alike.

Miranda Alamilla

Being raised in a hispanic household and in San Antonio, have obviously heard the story of La Llorona. However, I thought the story that I was always told was the only story of La Llorona there was. In reading this, I found out that my beliefs about La Llorona’s story were very false. According to this article, there is the Aztec version that has to do with the goddess Cihuacoatl, and hearing her cries were bad omens; or it could even be from when Cortez arrived to conquer Native Indians and La Malinche felt as though she betrayed her people. Reading this and finding out that La Llorona is not the only name and story there is was very interesting and I’m very happy I stumbled across this piece.