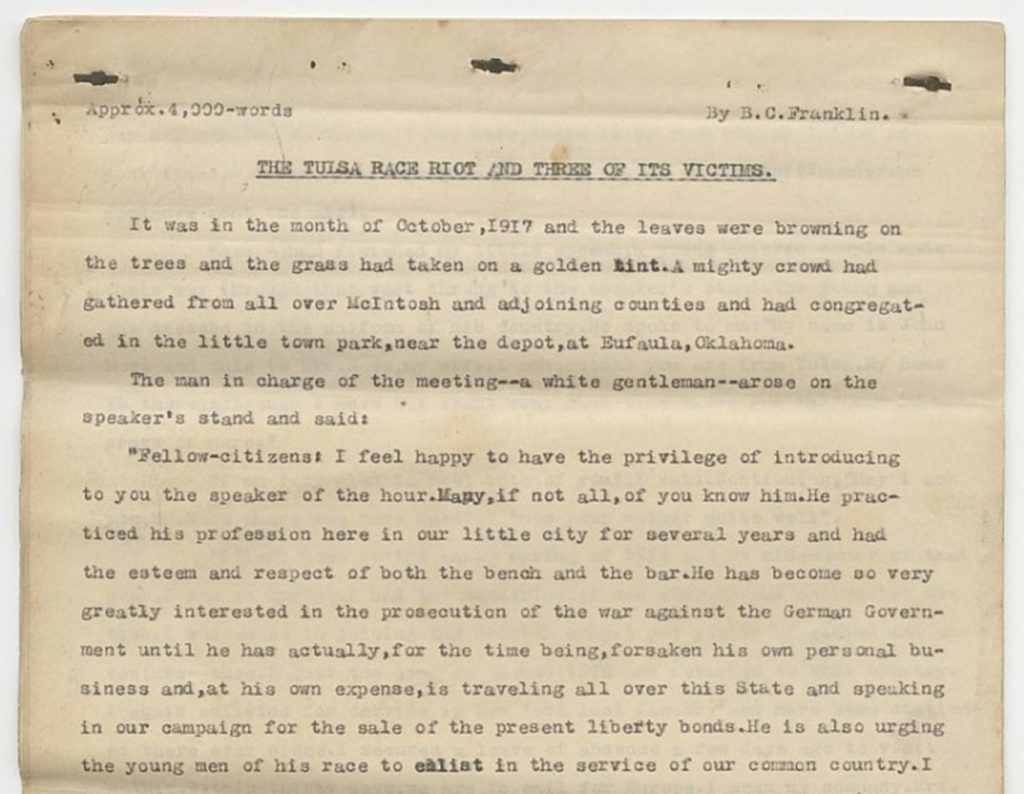

On the night of May 31, 1921, the black community of Tulsa Oklahoma’s Greenwood district would fall victim to one of the deadliest and most destructive episodes of racial violence in American history.1 As described in his manuscript, “The Tulsa Race Riot and Three of Its Victims,” Buck Colbert Franklin described the devastation of homes and businesses being bombed while black owners helplessly watched and were gunned down in the middle of the street that awful night. The prominent lawyer found himself frightened at the sound of multiple gunshots ringing in the air near his law office on Greenwood Avenue. Franklin witnessed the chaos of a feverish crowd, and suddenly he knew that he was witnessing a race riot, or “massacre,” as it was beginning to transpire.2

Buck Colbert Franklin was born on May 6, 1879, as one of ten children. Buck was named after his grandfather, who had been a slave and who had bought his family’s freedom. However, historians speculate that the freedom of the Franklins’ was actually credited to Buck’s father when he ran away from his plantation during the Civil War and then changed his name. Many years later, Franklin had come to Ardmore, Oklahoma, where he was practicing law. He often experienced racial prejudice there, because Ardmore was a predominantly white town. Franklin then decided to move to the predominantly black community of Rentiesville, Oklahoma. There, in 1915, Buck C. Franklin married Molly Parker and they began their family, having four children. One of them, son John Hope Franklin, would later become a notable historian and civil rights advocate. In 1921, Franklin moved away from his family, leaving them in Rentiesville, for the thriving black district of Greenwood in Tulsa Oklahoma. There he established a law office, and later his family joined him, once he was settled in. However, he would not know of the extremely high racial tensions that shaped the horrid events soon to take place just outside his law office.3

Racial tensions in Tulsa had been growing partly because of the prosperous community of Greenwood. Though historians debate how quickly Greenwood became the center of an affluent African-American community, by the early twentieth century, the economic success of Greenwood was well established, and it became known as “Black Wall Street.”4 The affluent black community consisted of thirty-five blocks, which was home to about six thousand residents, dozens of small businesses, newspapers, lawyers and doctors offices, and a school, all of which would be burned and destroyed due to the strong racist attitudes of the time. The popular aspirations of an African-American community would become the setting for a massive hate crime sparked by an incident that forever ruined the prosperity of the thriving area.5

On the afternoon of May 31, a newspaper article was released in the Tulsa Tribune titled “Nab Negro for Attacking Girl in Elevator,” which reported on a trial that involved a black man who allegedly attacked and attempted to rape a young white elevator operator earlier that morning.6 The trial debated of what actually happened in the elevator when Sara Page ran out screaming, alarming a nearby worker while nineteen-year-old Dick Rowland ran from the scene. Yet, the only reports of the incident came from police reports given by Sara Page and by the other witness, so it remained unclear what Rowland’s side of the story was, though speculations assumed that Rowland may have slipped and accidentally grabbed Page to steady himself.7 Nonetheless, the accusations were enough for police to arrest Rowland, and the white community spread talk of lynching him. Alarmed black citizens went to the courthouse, determined to protect Rowland from the angry white mob. The tension between the two parties in front of the courthouse steadily built during the afternoon hours and into the night.8 That’s when the riot erupted. “The panic, fear, and anger loosed by those first shots at the courthouse chased all reason from the streets of Tulsa.”9 The spark of a war between the black and white communities of Tulsa that dark night was lit, and there was no stopping it until the break of dawn.

Referring to the entire chaos of that grim night in Tulsa as a “riot” would be an understatement. What started out as a riot escalated to an all-out war zone as city leaders believed that, “what black Tulsans thought of as protecting a fellow African American through a display of unity, whites interpreted as an act of uprising.”10 Charles Daley, a major in the Oklahoma National Guard and assistant chief of the Tulsa Police Department, ordered the deployment of the national guard after he reported that, “thousands of persons… including several hundred women, and men armed with every available weapon in the city taken from every hardware and sporting goods store, swarmed… avenues watching the gathering volunteer army.”11 When martial law was declared, the police and national guard were sent to the major entrances of the district to prevent the anticipated attack on the white parts of the city.12 However, the police deputized and armed about 250 men that turned their attention to disarming and taking into custody the African Americans in Greenwood, killing anyone who did not surrender.13

That night, Buck C. Franklin did not know that the chaotic atmosphere outside his residence and office in Greenwood would turn into a “race war.” In his manuscript, Franklin described that from the setting of the dark skies, he could hear gunshots ringing in the distance. First assuming that they were just warning shots, he laid down, unbothered by the distant echoes. Then, he heard shots, one after another increasing as the hours of the night deepened, and he suddenly felt disturbed and anxious. It began to dawn on him that this was the response to the news article about the purported assault and rumors of a lynching. Distressed, Franklin called the sheriff’s office multiple times to find out any information, but each time, he could not get a connection. So he decided to leave his residence and hurry to his office to try and call from there. On Greenwood Avenue, Franklin, “found the streets congested with humanity and vehicles of all kinds,” before reaching his office to call the sheriff.14 Once again, his call did not connect to the sheriff’s office and he could not find out any information. He struggled for an hour to find out any news of what was going on from the people who were crowding the streets, but with a “mob mentality,” no one paid any attention to his worries.15

Then, Franklin returned to his hotel to lay back down as he, “soliloquized, ‘Here I am, a peaceable and law-abiding citizen, I have harmed no one–just like thousands of others of my race here–and yet I cannot now walk the street, upon a peaceful mission, in safety.’”16 At around midnight, Franklin awoke to the sound of bullets whistling in the air, raiding the exposed crowds. He wrote, “I saw the top of stand-pipe hill literally lightened up by the blazes that came from the throats of machine guns, and I could hear bullets cutting the air.”17 The fire of machine guns from the national guard would not be the only firestorm that he and the other black citizens would see that dreadful night. Buck C. Franklin witnessed planes circling mid-air dipping low towards the city as buildings all around began to burn from the top. The sound of hail echoed one after another, on to the next building and then the next, nonstop. The flames left behind from the aerial attacks roared through the early morning of June 1 with dense smoke covering the sky. “Lurid flames roared and belched and licked their forced tongues in the air. Smoke ascended the sky in thick, black volumes and amid it all, the planes–now a dozen or more in number still hummed and darted…”18 Through the massacre, he encountered a WWI veteran who had just returned home, a brave mother saving her child, and other citizens young and old, who did not survive the day “hell was on earth.”19

The fire department never showed up to try to stop the dozens of fires that consumed “Black Wall Street,” leaving the charred bones of buildings and businesses in deep ashes and ruins. After the massacre, it had been estimated that about 1,200 homes were destroyed and 300 people were killed. The remaining black citizens of Tulsa were rounded up and imprisoned for about eight days.20 The horror and destruction were documented through photos taken by newspapers, white citizens who celebrated the atrocity, and black citizens who mourned the loss of their home and remembered the violence.21

The manuscript that was written by Franklin detailing the events of that night also provided unique documentation of the unlawful attack committed by the city of Tulsa, Oklahoma. His eyewitness account of the black community being bombed by aerial attacks challenged the position of the city of Tulsa, who initially denied all participation in the cruel destruction. Before the Oklahoma Supreme court, Franklin led the legal battle against the City of Tulsa, challenging the ordinance that the victims of the attack could not rebuild their burnt down community. To this day, the victims of the 1921 Tulsa Massacre are still looking for justice and reparations as the Greenwood district has not been able to recover from the damage.22 Hundreds of families suffered at the hands of white citizens armed by the city, yet, this is not taught in schools across America. Although progress had been made from racial violence in the United States, the fight for social justice still remains and cannot be ignored.

- Randy Krehbiel, Tulsa 1921: Reporting a Massacre (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2019), 32. ↵

- Buck C. Franklin, “The Tulsa Race Riot and Three of Its Victims,” Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, August 22, (1931), 4. ↵

- Ephrem Yared, “Buck Colbert Franklin (1879-1960),” Blackpast (website), April 22, 2016, https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/franklin-buck-colbert-1879-1960/ ↵

- Randy Krehbiel, Tulsa 1921: Reporting a Massacre (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2019), 6. ↵

- Encyclopedia of African American History, 2010, s.v. “Tulsa, Oklahoma, Race Riot of 1921,” by Alfred Brophy. ↵

- Encyclopedia of Race and Crime Vol.2, 2009, s.v. “Tulsa Oklahoma, Race Riot of 1921,” by Vincent E. Miles. ↵

- Alfred L. Brophy, Reconstructing the Dreamland: The Tulsa Riot of 1921: Race, Reparations, and Reconciliation (Oxford; Oxford University Press, 2002), 24-25. ↵

- Encyclopedia of African American History, 2010, s.v. “Tulsa, Oklahoma, Race Riot of 1921,” by Alfred Brophy. ↵

- Randy Krehbiel, Tulsa 1921: Reporting a Massacre (Norman : University of Oklahoma Press, 2019), 45. ↵

- Randy Krehbiel, Tulsa 1921: Reporting a Massacre, (Norman : University of Oklahoma Press, 2019), 44. ↵

- Randy Krehbiel, Tulsa 1921: Reporting a Massacre, (Norman : University of Oklahoma Press, 2019), 44. ↵

- Randy Krehbiel, Tulsa 1921: Reporting a Massacre, (Norman : University of Oklahoma Press, 2019), 44. ↵

- Encyclopedia of African American History, 2010, s.v. “Tulsa, Oklahoma, Race Riot of 1921,” by Alfred Brophy. ↵

- Buck C. Franklin, “The Tulsa Race Riot and Three of Its Victims,” Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, August 22, 1931, 3. ↵

- Buck C. Franklin, “The Tulsa Race Riot and Three of Its Victims,” Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, August 22, 1931, 3-4. ↵

- Buck C. Franklin, “The Tulsa Race Riot and Three of Its Victims,” Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, August 22, 1931, 4. ↵

- Buck C. Franklin, “The Tulsa Race Riot and Three of Its Victims,” Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, August 22, 1931, 4. ↵

- Buck C. Franklin, “The Tulsa Race Riot and Three of Its Victims,” Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, August 22, 1931, 6. ↵

- Buck C. Franklin, “The Tulsa Race Riot and Three of Its Victims,” Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, August 22, 1931, 6. ↵

- Allison Keyes, “A Long-Lost Manuscript Contains a Searing Eyewitness Account of the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921,” Smithsonian (website), May 27, 2016, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/long-lost-manuscript-contains-searing-eyewitness-account-tulsa-race-massacre-1921-180959251/ ↵

- Alfred L. Brophy, Reconstructing the Dreamland: The Tulsa Riot of 1921: Race, Reparations, and Reconciliation (Oxford; Oxford University Press, 2002), 63. ↵

- Ephrem Yared, “Buck Colbert Franklin (1879-1960),” Blackpast (website), April 22, 2016, https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/franklin-buck-colbert-1879-1960/ ↵

60 comments

Irene Urbina

Amazing article! I had no idea about this massacre, and it is astonishing to read that such event happened. I really liked that you added parts of his manuscripts because it gives his perspective on the situation and show more feelings in the article. The imagery was excellent as well. It is sad to read how a lot of people died just because authorities did not intervene and just let the chaos continue. Thank you for sharing this part of history that is not taught in schools.

Cecilia Schneider

This article was so well written and truly captured my attention the entire time I was reading it! It is a tragically unfortunate event, and even more so when I reflect on the spurs of it. HOw easily could the same tragedy occur today? Maybe it would be in slight more control, but a riot ad fight could definitely wage at any moment I feel especially with the sensitivity and increasing major divide between parties and people.

Dylan Miller

This article was a great read! What happened at Tulsa was truly a tragedy, and learning about it is important to know about the oppression that many people experienced. The use of quotes from people who experienced it and the images used fully allows the audience to grasp the horrific situation that caused so much death and destruction of homes. I knew about the massacre, but being allowed to really dive deep and learn what happened is extremely impactful.

Luis Molina Lucio

I am not sure if I ever learned about this Tulsa Massacre of 1921 but now I actually know about this and how terrible it was. What strikes me the most was the fact that the City gave weapons to the Citizens which evidently was going to lead to a mess. It is just really mind blowing to think what White Americans would use as an excuse to go after African Americans. The more I learned about racist past the more I realize that human nature can be terrible. Overall very informative article that really taught me what the Tulsa Massacre was.

Jacob Galan

Very good use of imagery when talking about the massacre. I think what would be cool is that if you made another article talking about the trail and the go into more depth of both the girl and the man. Overall, it is sad that all this violence took place just because people could wait for the justice system to go through the process and see whether or not he did it or not.

Maria Jose Haile

I love how the author choses to write about an unfortunate time period but brings light to the scenario. This scenario brings light to how we have changed as a nation to combat racism. I am happy about that we have came so far from these times. Unfortunately, some parts of this history is not taught. However, the thing about racism is that- it is taught through our actions and how portray the other races. You did a great job telling the unknown story of something that we should all know so congrats on the award.

Aaron Sandoval

This article was really well done and written and the author did a good job of covering an important topic that is rarely covered. I had only heard about this event once in a history class in high school and it was covered very briefly, so to find and read this article really broadened my understanding of what occurred, the author did a great job of laying out the events. It is truly sad to know that tragic events such as this occurred.

Camryn Blackmon

Hi Alicia,

I love that you wrote about an event seldom taught and discussed in history but is extremely important as many people died an entire community was destroyed. Besides discussing the event itself, I love that you took time to describe the city’s success, significant individuals who were a part of the community to tell their stories, and how the attack began. It is also important that you take the time to talk about people and groups that attacked and those that did not respond, such as the fire department. These parts of your article are very powerful and bring forward a forgotten but tragic time in history that is also prevalent today.

Paul Garza

I absolutely love that you chose to write about this unfortunate time in history. Not many people know of this massacre. I appreciate when authors choose to tell these unpleasant but true parts of our history. Just as you mentioned in the end, this is not something taught about in school. Our curriculums are centered around white and indoctrinated teachings that erase the history of black, indigenous, Latinx, etc. Although these stories can be difficult to swallow, it is vital to learn of all sides of United States history.

Azariel Del Carmen

It is a shame how society in the past was with each other just because of color/race between one another and such. The lack of help by the city the people served and worked in to make the city money in taxes and such is a shame to see since they didn’t even bother to pick up the phone and send fire fighters to battle fires and either protect or explain the situations. I also find it odd that the city tried to pinned itself as innocent despite what the people of the area did which it should have taken responsibility for due to these actions and lack of response to it.