The heightened awareness of environmental issues caused by human activity has spurred interest in maximizing sustainability efforts – that is, efforts that benefit the well-being of the environment in the future. Efforts include reducing carbon emissions, lowering pollution, and even consuming less beef to reduce methane emissions. Moreover, people are also engaging in climate change protests, demanding climate justice (see Figure 1). This awareness has increased focus on how decision making should incorporate scientific sustainability efforts. The role of science in informing political decisions has been an important factor in advancing sustainability efforts, and there has been a new rise in understanding the production of actionable knowledge; defined as “…that knowledge required to implement the external validity [relevance of research] in the world”.1 The term roots in Aristotle’s idea of Praxis, which involves the process of realizing theory and practice. A concept that may result in helping sustainability science researchers to effectively achieve sustainability goals.

In an effort to realize this goal, many research institutions have called for the co-production of actionable knowledge. Co-production is essential to ideas in the theory and practice of knowledge and governance for global sustainability.2 Despite its essential nature, the definition of co-production is not a concrete one.3 Although this generates a barrier itself, the concept involves bringing researchers and users of science into a collaborative process.4 When the calls for actionable knowledge are answered, however, results have focused largely on the procedural methods, instead of its use in actions that further sustainability. Despite the value of the procedure involved in conducting research, perhaps a better understanding of the relationship between science and use is needed to obtain actionable knowledge. Theoretical collaborative forms of engagement aim towards co-production of knowledge with the people who are likely to use the knowledge in making changes in their organizations, communities, or environments. Knowledge making and decision making can thereby continually reshape society to better achieve sustainability efforts.4 Enabling this type of knowledge creation can help address environmental issues we face today.

However, with new efforts to obtain actionable knowledge, the fundamental question that arises is: What is use? (Note: For clarity, the word use is italicized when considered as a noun). What constitutes as use and how can researchers measure use? Intuitively, use is the application of knowledge in policy to achieve sustainability goals. Research has, however, long-highlighted the methodological challenges of assessing research use. Where methodological challenges can be barriers to accurate data accumulation that attempt to coherently define use. These challenges include defining outcome variables of use, identifying independent variables, identifying users, and facilitating user recall of uses.6 In essence, what is the outcome of use? Is use interdependent? Can use be repeated by the targeted user? What is use and how can we obtain it? Several scientists have created models intended to define use, but ultimately use remains as clear as mud. These challenges have driven researchers to attempt to uncover a concrete definition of use that may contribute to the efficacy of sustainability efforts.

Recent research by James C. Arnott and Maria Carmen Lemos, of the University of Michigan and the Aspen Global Change Institute, attempts to tackle the issue of use as it relates to environmental sustainability through an intensive study including 32 grant recipients of the coastal area management grant program funded from 1998 to 2014 through National Estuarine Reserve Research System –a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) applied coastal research program.7 The purpose is to examine the tension between clearly understanding use and the reality of its complexity. For this purpose, Arnott and Lemos conducted an in-depth case study of how grant recipients characterize attributes of knowledge use — when reflecting on the process and outcomes resulting from their completed projects — is carried out. The stated aim of grant recipients is to produce actionable knowledge to inform sustainable resource management in coastal areas. Researchers specifically asked members of the NOAA-funded grant teams, “…to what extent do deliberate approaches to producing usable science yield clearer and more specific description of knowledge use?” 7 Grant recipients were asked to reflect on whether these descriptions and uses comply with the expectations of funders and institutions? If not, what are the implications of this disconnect between expectations and actual outcomes for developing new approaches to understand and inform society of the use of knowledge for sustainability? Grantees were then interviewed to expand on how their findings contribute to use, users, and broader impacts on coastal sustainability.

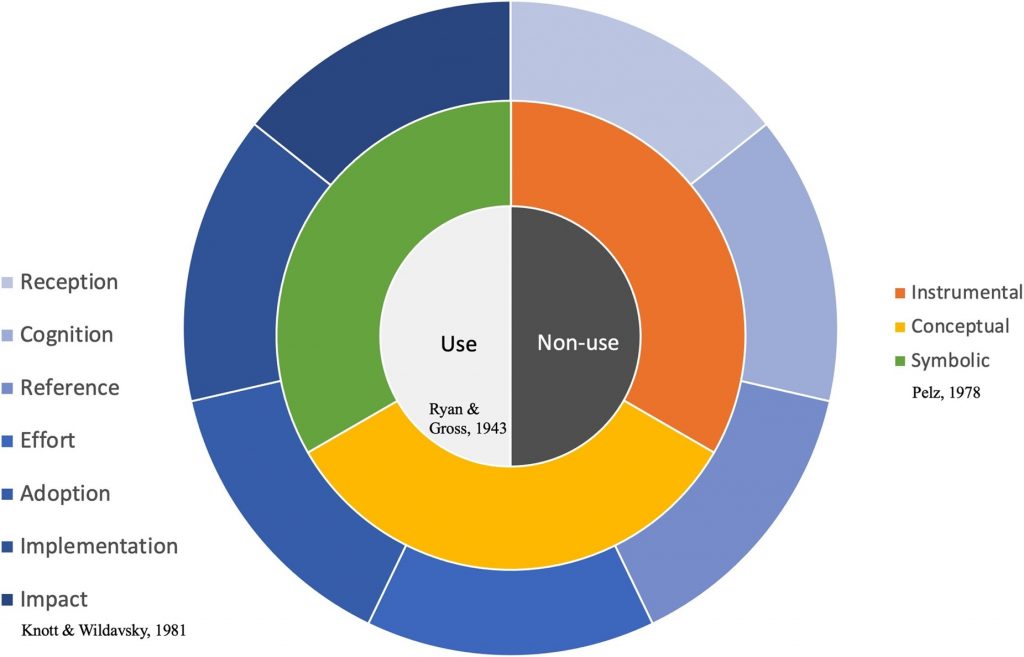

A typology is simply a classification framework organized to a general type, and it can be viewed as a method of defining knowledge use. To measure knowledge use Arnott and Lemos used an established typology that defines usability, namely the DC Pelz Typology. Introduced in the late 1970s, the DC Pelz Typology analyzes use in three main classifications:

- Instrumental use–when knowledge provides direct input to decision making,

- Conceptual use–when knowledge is used more abstractly to inform background understanding of a topic, and

- Symbolic use–when knowledge is employed in more strategic methods to justify already established commitments.9

In an effort to obtain a clearer definition of use, Arnott and Lemos blended the DC Pelz typology with the typology of Knott and Wildavsky (est. 1981), which describes use based on the different stages of the policy process across which knowledge is adopted: recognition, cognition, reference, effort, adoption, implementation, and impact (see Figure 2). These stages of use attempt to define how use is processed from its reception to its impact.

Next, interviews were conducted using a structured interview process, audio recorded, and transcribed using a third party transcription service. The structure process involved coding interviews based on five themes identified in studies as barriers to advancing the study of knowledge use9: how interviewees identified uses and users; and how they tracked, attributed, and reported outcomes associated with use (see Figure 3).

After conducting the interviews, however, grant recipients still could not clearly define use for their research, clearly identify users, nor could they clearly present evidence of broader impacts. Of thirty-two grant teams, eleven did not cite any evidence or even provide anecdotal examples of use when interviewed. When asked about use attribution (how use is ascribed), grantees generally failed to provide detailed explanations. Three main reasons were offered to explain this relative failure of grant recipients to consider how their research results could be used:

- Either there was not sufficient time or money to achieve something that was usable,

- There were technological limitations that either rendered the resulting knowledge or tools nonfunctional, or

- The results were far too complex for intended users.

Still, grantees in the NOAA applied coastal research program argued that their findings were pivotal, yet found it difficult to specifically address usability.9 This generates a deep problem for sustainability action. If researchers cannot compose actionable knowledge how can an advance of sustainability efforts in policy be envisioned?

Aligning knowledge and action for global sustainability is essential to the human future. When properly understood, co-production offers a powerful framework for guiding that work. However, the ongoing quest to identify use narrowly in terms of targeted users would restrict the ability to envision and explain the potentially transformational impacts of knowledge. Elusive definitions in actionable knowledge research contribute to the confusion of both researchers and institutions. Although the NOAA coastal grant program study seems to offer an example of negative results with respect to the development of actionable knowledge, perhaps there is still greater analysis of actionable knowledge to be unraveled that may potentially foster knowledge usability to benefit sustainability approaches.12 Perhaps, actionable knowledge is a relatively new concept that is in an early stage of development. Therefore, rather than considering the lack of clarity with respect to use as a limitation, addressing the inherent confusion at the science-policy interface on the creation, results, and use of new information may in itself be the principal path to better understanding the drivers of effective sustainability action.

- Miller, C. A., & Wyborn, C. (2020). Co-production in global sustainability: Histories and theories. Environmental Science & Policy, 113, 88–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2018.01.016. ↵

- Miller, C. A., & Wyborn, C. (2020). Co-production in global sustainability: Histories and theories. Environmental Science & Policy, 113, 88–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2018.01.016. ↵

- van der Hel, S. (2016). New science for global sustainability? The institutionalisation of knowledge co-production in Future Earth. Environmental Science & Policy, 61, 165–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2016.03.012. ↵

- Mach, K. J., Lemos, M. C., Meadow, A. M., Wyborn, C., Klenk, N., Arnott, J. C., Ardoin, N. M., Fieseler, C., Moss, R. H., Nichols, L., Stults, M., Vaughan, C., & Wong-Parodi, G. (2020). Actionable knowledge and the art of engagement. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 42, 30–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2020.01.002. ↵

- Mach, K. J., Lemos, M. C., Meadow, A. M., Wyborn, C., Klenk, N., Arnott, J. C., Ardoin, N. M., Fieseler, C., Moss, R. H., Nichols, L., Stults, M., Vaughan, C., & Wong-Parodi, G. (2020). Actionable knowledge and the art of engagement. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 42, 30–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2020.01.002. ↵

- Arnott, J. C., & Lemos, M. C. (2021). Understanding knowledge use for sustainability. Environmental Science & Policy, 120, 222–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2021.02.016. ↵

- Arnott, J. C., & Lemos, M. C. (2021). Understanding knowledge use for sustainability. Environmental Science & Policy, 120, 222–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2021.02.016. ↵

- Arnott, J. C., & Lemos, M. C. (2021). Understanding knowledge use for sustainability. Environmental Science & Policy, 120, 222–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2021.02.016. ↵

- Arnott, J. C., & Lemos, M. C. (2021). Understanding knowledge use for sustainability. Environmental Science & Policy, 120, 222–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2021.02.016. ↵

- Arnott, J. C., & Lemos, M. C. (2021). Understanding knowledge use for sustainability. Environmental Science & Policy, 120, 222–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2021.02.016. ↵

- Arnott, J. C., & Lemos, M. C. (2021). Understanding knowledge use for sustainability. Environmental Science & Policy, 120, 222–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2021.02.016. ↵

- Cozzens, S. E. (1997). The knowledge pool: Measurement challenges in evaluating fundamental research programs. Evaluation and Program Planning, 20(1), 77–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0149-7189(96)00038-9. ↵

5 comments

Madeline Chandler

This was an extremely well-written article, and it was so detailed. I have heard of the ideas to “save” Earth through green decisions. This article truly in such depth describes what is going on plus ideas to remedy saving our Earth. The charts with graphs and evidence made your argument even more detailed and persuading. Through this article, the audience can tell how much the author cares about environmental issues.

Phylisha Liscano

This was a very interesting and informative article. The article topic was a very topic one but you made it explained everything very well which allowed me to easily follow along. The amount of information in this article made it very informative and the charts that you included helped with my understanding. I can tell lots of research was put into your article and you provided lots of information. This topic was a very interesting one and you did a great job telling a story. Overall great article and well done.

Carlos Hinojosa

I understand what you’re getting at with this article. The idea of simplifying recycling or just cutting back but to be honest I don’t think our planet can be saved anymore. The only way I can see it working is two ways, the entire world works together to stop it and I mean everyone, or someone develops a wonder invention that reverses the damage that has already been done. Besides that, this was a very well-made article. Good job.

Kanum Parker

This is a interesting subject because it is a difficult one. I would say that the use is different from each person and the important it is to them. As the chart shows it is well even in all aspects. That being said all that needs to be done is going to take time. How long? They don’t probably know but the knowledge is there and can be applied. It is just going to take awhile for people to catch one and understand. All of this is a process we need to hurry up so we can improve.

Isaac Fellows

First of all, your use of graphics and data charts in this article look really good. Not only are they easy to read, but they just mesh well with into the layout of the piece. Second, this was a really well done article and has me looking to learn more. I am definitely going to seek more information on actionable knowledge in the future.

Great article, well done.