“You can measure the extent of physical damage done to cities but how to gauge what has happened to human beings–that is incalculable.”–Eleanor Roosevelt 1

Less than three decades after the First World War, where more than seventeen million soldiers and civilians were killed, Europe was once again involved in a major conflict.2 In 1941, the Second World War, which involved Germany, Japan, and Italy against Great Britain, the United States, and the Soviet Union, swept the world in a firestorm of death and destruction beyond that of the Great War of 1914-1918. Over fifty million people died in the Second World War and the terrible atrocities committed, such as the Holocaust–the genocidal murder of nearly eleven million Jews, gypsies, homosexuals, Poles, and Soviet POWs, as well as other minorities–will never be forgotten.3 As a matter of fact, the horrible death of these fifty million citizens of the world was the trigger for the establishment of universal human rights.

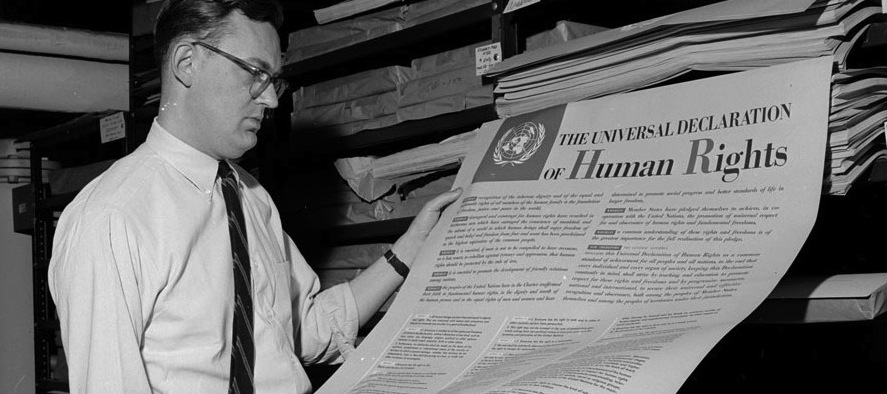

In 1945, when Germany was defeated, the peoples of the world noticed something more than damaged cities; they noticed the human cost that was paid because of the thirteen years of Nazi rule in Germany. The priority in the world moved away from state security, which focused on countries protecting themselves from external threats, to human security, which focused on freedom from violence, from the fear of violence, and the protection of the people. In 1946, during the first session of the United Nations General Assembly, people from various legal and cultural backgrounds of all regions of the world came together to find a solution and to promise future generations that wars and conflicts in which millions of people would be murdered in cold blood would never happen again. So, John Humphrey of Canada along with Rene Cassin of France, Eleanor Roosevelt of the United States, Peng Chang of China, and Charles Malik of Lebanon, drafted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.4

Only six of the eighteen members of the drafting committee are mentioned as creating the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, but each person involved in the creation of the Declaration made important contributions. For example, Humphrey produced the very first draft of the Declaration. Cassin was an important player in the deliberations held throughout the three sessions of the Commission on Human Rights. During the creation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights there were increasing East-West tensions, so Roosevelt used her credibility with both superpowers to steer the drafting process toward its successful completion. Chang conveyed Chinese concepts of human rights to the other delegates and resolved many of the issues that were brought up during the negotiation process. Lastly, Malik was a major force in the debates surrounding key provisions of the Declaration.5 Everyone had to work together; after all, this document was going to change how the world viewed its people.

It took took nearly two years, and seven different drafting stages, but on December 10, 1948, fifty-six countries came together for the United Nations General Assembly meeting at the Palais de Chaillot in Paris, France. During this meeting the countries were going to determine whether or not the Universal Declaration of Human Rights would be adopted. This was also the fourth time everyone at the United Nations had seen the Declaration, and it was also the fourth time that they had had the opportunity to amend what the writers of the Declaration had done. On this day, many amendments were proposed, but only one significant modification was made. For the most part, on this day, the Declaration writers took their time to congratulate themselves and each other. A little before midnight, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was adopted, with a vote of 48 to 0 and 8 abstentions.6

We know who wrote the document, why the document was written, and when and where the document was adopted, but the big question is, what did this Declaration identify as human rights? The document itself is composed of thirty Articles, each and every one explaining different rights. The easiest way to understand the content of the document is to understand its division into three different “generations” or categories of rights, each one having a different origin and representing different aspects on human rights. The three categories are civil and political rights, social and economic rights, and solidarity rights.

Articles two through twenty-one from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) make up the first generation of rights, which are the Civil and Political Rights. These rights focus mainly on the rights of the individual and place an emphasis on the responsibility of the government to refrain from being oppressive in the lives of its own citizens.7 Civil-political human rights include two sub-types: norms relating to physical and civil security–for example, prohibitions on torture, slavery, inhumane treatment, arbitrary arrest, and positively, a general sense of equality before the law; and norms pertaining to civil-political liberties or empowerment–for example, freedom of thought, of conscience, and of religion, freedom of assembly and of voluntary association and political participation in one’s society.

The second generation of rights are the Social and Economic Rights, which include Articles twenty-two through twenty-six from the UDHR. These rights stem from the Western socialist tradition and they focus on social equality and the responsibility of the government to provide for its citizens.8 Second generation rights include rights to be employed in a just and favorable condition, rights to food, housing, and health care, as well as social security and unemployment benefits.

Articles twenty-seven and twenty-eight are known as the Solidarity Rights. They are called solidarity rights because in order for them to be enforced, the cooperation of all countries is needed. They constitute a broad class of rights that have gained acknowledgment in international agreements and treaties, but are more contested than the other rights. They have been expressed largely in documents as the “soft law,” such as the 1992 Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, and the 1994 Draft Declaration of Indigenous Peoples’ Rights.9

Although the Declaration was adopted, it was adopted as a non-binding document, meaning that if a country does not follow it, there would be no consequences. Even though it is not legally binding, the Declaration has been adopted in or has influenced most national constitutions since 1948. It has also been taken up as an international norm, which is something that is not quite law, but that the international community assumes to be acceptable. It has also served as the foundation for a growing number of national laws, international laws, and treaties, as well as for a growing number of regional, sub-national, and national institutions protecting and promoting human rights. As time has passed, the Declaration has formed part of customary international law (both laws and norms that are so accepted in the international community that a violation of them is subject to punishment even if someone is not a signatory to it). And it is a powerful tool in applying diplomatic and moral pressure to governments that violate any of its articles.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights has inspired many individuals and policymakers around the world to work toward a better world. Today there are around two hundred assorted declarations, conventions, protocols, treaties, charters, and agreements dealing with the realization of human rights in the world. Of these postwar documents, no fewer than sixty-five mention the Universal Declaration of Human Rights as their source of authority and inspiration.10 Today we contemplate the legacy of the document because it is the foundation of the idea that everyone should have equal basic human rights no matter where one lives or how one lives. It shines a light on the protection of humans, and although we have a long way to go before we can say that human rights are now being observed all over the world, I believe that if we have this Declaration in mind at all times, someday, hopefully in the near future, all of humanity will have basic human rights.

Primary Source

Universal Declaration of Human Rights 11

Preamble

Whereas recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world,

Whereas disregard and contempt for human rights have resulted in barbarous acts which have outraged the conscience of mankind, and the advent of a world in which human beings shall enjoy freedom of speech and belief and freedom from fear and want has been proclaimed as the highest aspiration of the common people,

Whereas it is essential, if man is not to be compelled to have recourse, as a last resort, to rebellion against tyranny and oppression, that human rights should be protected by the rule of law,

Whereas it is essential to promote the development of friendly relations between nations,

Whereas the peoples of the United Nations have in the Charter reaffirmed their faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person and in the equal rights of men and women and have determined to promote social progress and better standards of life in larger freedom,

Whereas Member States have pledged themselves to achieve, in cooperation with the United Nations, the promotion of universal respect for and observance of human rights and fundamental freedoms,

Whereas a common understanding of these rights and freedoms is of the greatest importance for the full realization of this pledge,

Now, therefore, The General Assembly, Proclaims this Universal Declaration of Human Rights as a common standard of achievement for all peoples and all nations, to the end that every individual and every organ of society, keeping this Declaration constantly in mind, shall strive by teaching and education to promote respect for these rights and freedoms and by progressive measures, national and international, to secure their universal and effective recognition and observance, both among the peoples of Member States themselves and among the peoples of territories under their jurisdiction.

Article I

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

Article 2

Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status. Furthermore, no distinction shall be made on the basis of the political, jurisdictional or international status of the country or territory to which a person belongs, whether it be independent, trust, non-self-governing or under any other limitation of sovereignty.

Article 3

Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of person.

Article 4

No one shall be held in slavery or servitude; slavery and the slave trade shall be prohibited in all their forms.

Article 5

No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.

Article 6

Everyone has the right to recognition everywhere as a person before the law.

Article 7

All are equal before the law and are entitled without any discrimination to equal protection of the law. All are entitled to equal protection against any discrimination in violation of this Declaration and against any incitement to such discrimination.

Article 8

Everyone has the right to an effective remedy by the competent national tribunals for acts violating the fundamental rights granted him by the constitution or by law.

Article 9

No one shall be subjected to arbitrary arrest, detention or exile.

Article 10

Everyone is entitled in full equality to a fair and public hearing by an independent and impartial tribunal, in the determination of his rights and obligations and of any criminal charge against him.

Article 11

1. Everyone charged with a penal offence has the right to be presumed innocent until proved guilty according to law in a public trial at which he has had all the guarantees necessary for his defence.

2. No one shall be held guilty of any penal offence on account of any act or omission which did not constitute a penal offence, under national or international law, at the time when it was committed. Nor shall a heavier penalty be imposed than the one that was applicable at the time the penal offence was committed.

Article 12

No one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to attacks upon his honour and reputation. Everyone has the right to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks.

Article 13

1. Everyone has the right to freedom of movement and residence within the borders of each State.

2. Everyone has the right to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his country.

Article 14

1. Everyone has the right to seek and to enjoy in other countries asylum from persecution.

2. This right may not be invoked in the case of prosecutions genuinely arising from non-political crimes or from acts contrary to the purposes and principles of the United Nations.

Article 15

1. Everyone has the right to a nationality. 2. No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his nationality nor denied the right to change his nationality.

Article 16

1. Men and women of full age, without any limitation due to race, nationality or religion, have the right to marry and to found a family. They are entitled to equal rights as to marriage, during marriage and at its dissolution.

2. Marriage shall be entered into only with the free and full consent of the intending spouses.

3. The family is the natural and fundamental group unit of society and is entitled to protection by society and the State.

Article 17

1. Everyone has the right to own property alone as well as in association with others.

2. No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his property.

Article 18

Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; this right includes freedom to change his religion or belief, and freedom, either alone or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship and observance.

Article 19

Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.

Article 20

1. Everyone has the right to freedom of peaceful assembly and association.

2. No one may be compelled to belong to an association.

Article 21

1. Everyone has the right to take part in the government of his country, directly or through freely chosen representatives.

2. Everyone has the right to equal access to public service in his country.

3. The will of the people shall be the basis of the authority of government; this will shall be expressed in periodic and genuine elections which shall be by universal and equal suffrage and shall be held by secret vote or by equivalent free voting procedures.

Article 22

Everyone, as a member of society, has the right to social security and is entitled to realization, through national effort and international co-operation and in accordance with the organization and resources of each State, of the economic, social and cultural rights indispensable for his dignity and the free development of his personality.

Article 23

1. Everyone has the right to work, to free choice of employment, to just and favourable conditions of work and to protection against unemployment.

2. Everyone, without any discrimination, has the right to equal pay for equal work.

3. Everyone who works has the right to just and favourable remuneration ensuring for himself and his family an existence worthy of human dignity, and supplemented, if necessary, by other means of social protection.

4. Everyone has the right to form and to join trade unions for the protection of his interests.

Article 24

Everyone has the right to rest and leisure, including reasonable limitation of working hours and periodic holidays with pay.

Article 25

1. Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond his control.

2. Motherhood and childhood are entitled to special care and assistance. All children, whether born in or out of wedlock, shall enjoy the same social protection.

Article 26

1. Everyone has the right to education. Education shall be free, at least in the elementary and fundamental stages. Elementary education shall be compulsory. Technical and professional education shall be made generally available and higher education shall be equally accessible to all on the basis of merit.

2. Education shall be directed to the full development of the human personality and to the strengthening of respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms. It shall promote understanding, tolerance and friendship among all nations, racial or religious groups, and shall further the activities of the United Nations for the maintenance of peace.

3. Parents have a prior right to choose the kind of education that shall be given to their children.

Article 27

1. Everyone has the right freely to participate in the cultural life of the community, to enjoy the arts and to share in scientific advancement and its benefits.

2. Everyone has the right to the protection of the moral and material interests resulting from any scientific, literary or artistic production of which he is the author.

Article 28

Everyone is entitled to a social and international order in which the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration can be fully realized.

Article 29

1. Everyone has duties to the community in which alone the free and full development of his personality is possible.

2. In the exercise of his rights and freedoms, everyone shall be subject only to such limitations as are determined by law solely for the purpose of securing due recognition and respect for the rights and freedoms of others and of meeting the just requirements of morality, public order and the general welfare in a democratic society.

3. These rights and freedoms may in no case be exercised contrary to the purposes and principles of the United Nations.

Article 30

Nothing in this Declaration may be interpreted as implying for any State, group or person any right to engage in any activity or to perform any act aimed at the destruction of any of the rights and freedoms set forth herein.

- Eleanor Roosevelt, “My Day, February 18, 1946,” The Eleanor Roosevelt Papers Digital Edition (2008). ↵

- International Encyclopedia of the First World War, October 2014, s.v. “War Losses,” by Antoine Prost. ↵

- Encyclopædia Britannica, February 2017, s.v. “World War II,” by John Graham Royde-Smith. ↵

- Encyclopædia Britannica, September 2009, s.v. “The Universal Declaration of Human Rights,” by George J. Andreopoulos. ↵

- United Nations, “Drafting of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights,” Official Website of the United Nations, http://research.un.org/en/undhr/draftingcommittee (accessed April 17, 2017). ↵

- Johannes Morsink, The Universal Declaration of Human Rights: Origins, Drafting & Intent (Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999), 11-12. ↵

- D. Neil Snarr, Introducing Global Issues: The Quest for Universal Human Rights (Colorado: Lynne Rienner Publishers, Inc., 2016), 84-85. ↵

- D. Neil Snarr, Introducing Global Issues: The Quest for Universal Human Rights (Colorado: Lynne Rienner Publishers, Inc., 2016), 88-89. ↵

- D. Neil Snarr, Introducing Global Issues: The Quest for Universal Human Rights (Colorado: Lynne Rienner Publishers, Inc., 2016), 89-91. ↵

- Johannes Morsink, The Universal Declaration of Human Rights: Origins, Drafting, and Intent (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999), 20. ↵

- United Nations, “The Universal Declaration of Human Rights,” Official Website of the United Nations, http://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/ , accessed April 28, 2017. ↵

54 comments

Thiffany Yeupell

For the Universal Declaration of Human Rights to take two years for drafting and to finally come into finalization and only reach a nonbinding status after adoption, it seems that the efforts of the drafters may have been diminished. It may have provided a basis for future documents and allow for the issue of human rights to become a more focused subject in the new documents that would follow after its completion, but the declaration has an ‘informal’ power (if you will). With its layout and the subjects it has touched upon, the declaration seems sufficient, but I would imagine when the world is ready to recognize and add power to such a document addressing the given concerns, more revisions and drafting sessions would be ahead of the document if the nations (a majority of them, at the least) were to cooperate.

Savannah Alcazar

I enjoyed this read. I did not know about the Universal Declaration of Human Rights before reading this article; probably because American education is hyper focused on itself. The article title embodies the text. I think it’s peculiar how the Universal Declaration of Human Rights is non-binding to where there are no repercussions when countries do not follow it. I like how you included that it inspired other countries in their own constitutions. I also like how you included the numbers of the actual vote of 48 to 0 with 8 abstentions.

Matthew Swaykus

The author chose a great quote for the article that helps define the reasons behind the United Nation’s decision to declare human rights as a universal standard. I believe it is interesting that the author chose to lay out what this document truly entailed with what practices have been determined to be inhumane and unjust. It forces you to think about some of the events happing in the world today from political leaders like the newly elected president of Brazil supporting the use of torture to issues of voter suppression in the United States.

Christopher Hohman

Nice article. The United Nation’s declaration of Universal Human Rights was quite an important moment in the history of our world. After coming off the second World War there was a need to reevaluate how nations on Earth treat not just one another but also their own citizens. It is cool that the individuals who drafted the document worked together as a team to create the document. It was not just the actions of one person, but of everyone in the group.

Cynthia Rodriguez

In my senior seminar class, we have been studying the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. It was not until this class that I actually read the entire document. I thought it was a nice touch that you added the primary source for the readers to look at. I find it interesting that several amendments were proposed that December 10, but there was only one significant change made. This was a great article about a great document. Good job!

Natalie Juarez

I appreciate this article very much due to the fact that it was well organized and informative on the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The history and facts on why the document was created because of the atrocious events that happened during World War II, give a clear picture on the motivation behind it, as well as the influence it can have to change people’s mindsets on the importance of human rights to get them to care. I wish that the document had power, so that it isn’t really just a moral compass. Overall, great job!

Arieana Martinez

This is an awesome way to inform everyone about the Universal Declaration of Human Rights! I like the creative way that the author talks about the articles and how they came to be. This informed me as a student, voter, and citizen who wants to make a positive impact on the community. Highly recommend for anyone wanting to understand more about our rights.

Gabriela Murillo Diaz

The article discusses the purpose of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and how the world wars were trying to call attention to all the violations that occurred during times of war. The article was very informative in providing background information about the declaration, but I found it to be lengthy and uninteresting. I think that more information about the people that wrote the Human rights would have provided more interesting content for the article.

Stephanie Nava

This is a great article for anyone who wants to learn more about the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. I like how the author separated the type of rights that went into the declaration. I also like how the author included the actual declaration after the article was done. Overall this was a very informative article and also very helpful.

Matthew Wyatt

This is a great article about a pivotal moment in the history of international law. However, it could still use a few minor edits. For example, the word “took” is repeated in the first sentence of the fourth paragraph. Also, the last sentence of the last paragraph is a run-on that could be divided into at least two sentences. By making these minor adjustments, this article will really shine as a great piece.