It was just after dawn that the silence was broken. The first explosions echoed through the hills, waking families from sleep, not to birdsong, but to horror. In this small Palestinian village—circled by olive trees and low, stone houses—people fell out of sleep and into chaos.

Women reached for children instinctively. Men grabbed what they could: marriage certificates, a few coins, maybe a bag of lentils. The air was thick with the smell of dust and something else—something burning. People yelled to one another as they flooded onto the small streets, still barefoot, some still half-dressed. One mother had her baby in one arm and a tin of water in the other. One boy clutched a house key that was rusted and did not speak.

Smoke wreathed off rooftops. A goat somewhere bleated in bewilderment. There was no strategy—only motion. Away.

They had already heard about Deir Yassin—what had happened there a few days earlier. But it did not seem real. Over a hundred Palestinians were killed in a brutal raid. Some said it could not be. But now, with the shelling coming closer, the doubt vanished. The horror became real.1

This was not a solitary village under attack—it was one of many. Historians later documented how, in the months leading up to this moment, Zionist militias had begun enacting Plan Dalet, a military offensive intended to seize territory in advance of the British retreat. Dozens of towns were emptied—some by intimidation, others by violence. Haifa had already fallen. Jaffa would be next.2

By the end of that year, more than 700,000 Palestinians would be displaced—forced from their homes, never to be seen again. None of the villagers that morning knew what lay ahead. They only knew they had to flee. What they left behind them—homes, memories, olive groves passed down for centuries—would not be there when they came back. Most would never come back at all.3

This was the Nakba. It began not with a proclamation or a skirmish. It commenced, for many, with the boom of artillery before dawn—and the understanding that all that was familiar was already slipping away.

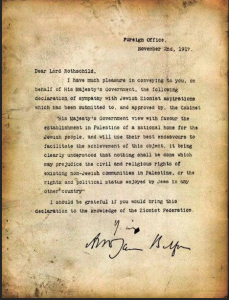

To understand how a tranquil Palestinian village could be disrupted by shelling in 1948, we must go back three decades to a short but important letter that changed the course of Middle Eastern history. British Foreign Secretary Arthur James Balfour, on 2 November 1917, issued what has become known as the Balfour Declaration, a public statement of British support for “the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people,” on condition that “nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities.”4

Although tactfully insincere in language, the impact of the declaration was revolutionary. It was issued at a time when Britain had not yet acquired possession of Palestine—still an Ottoman province—but had already begun to form its post-war imperial plans. The British simultaneously made contradictory promises to Arabs and Jews, promising Arab independence in order to secure war support while secretly negotiating with Zionist leaders and imperial powers. As Rashid Khalidi argues, this, too, was a policy of settler colonial rule cloaked in diplomatic ambiguity.5

The Balfour Declaration was eventually incorporated into the League of Nations Mandate for Palestine in 1922, de facto granting it international legitimacy. It was also the beginning of British policy administering procedure, which increasingly yielded to the Zionist project. Under British rule, Jewish immigration into Palestine grew immensely, especially with the rise of European fascism and the aftermath of the Holocaust during World War II. In 1947, the Jewish population had grown from less than 10% in 1917 to about 33%, with huge political, economic, and paramilitary networks.

To the indigenous Arab population—then the vast majority—this influx introduced more land purchases, job displacement, and mounting tensions. Palestinian resistance movements were brutally repressed by British authorities, especially during the Arab Revolt of 1936–1939, which was met with brutal counter-insurgency measures. The seeds of conflict to come were being planted not only through local clashes, but through international policy that privileged one group’s interests over another’s rights.6

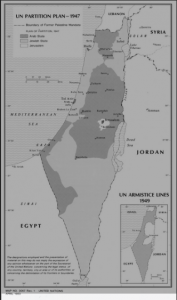

By the end of World War II, Britain’s empire was breaking down, and Palestine was an unsustainable colonial burden. Early in 1947, Britain transferred the “Palestine question” to the newly established United Nations. The next autumn, the UN General Assembly voted on Resolution 181, the UN Partition Plan, for partitioning Palestine into two independent states—Arab and Jewish—under international administration for Jerusalem due to its religious significance.

Even though partition was touted as a compromise, the conditions were grossly unequal. The Jewish minority, who numbered some one-third of the population and controlled less than 7% of the land, would be allotted over 55% of the land, including much of the fertile coastal plain. The Palestinian Arab majority, who were more deeply rooted in the country, would be allotted only 45%—chiefly dispersed, non-contiguous plots in the hills and desert.7

The reaction was immediate and polarizing. Zionist leaders welcomed the plan, though there were some who saw the borders as inadequate and considered it, at best, a staging ground for still more expansion down the road. Arab and Palestinian leaders rejected the plan outright as a colonial imposition on their sovereign right of self-determination.8

The following months saw growing violence—first in the form of internal unrest, and then as militia warfare. Zionist paramilitary groups, including the Haganah, Irgun, and Lehi, began engaging in preemptive strikes to acquire territory and exert control before Britain’s final withdrawal in May 1948. The groups struck Arab settlements within the Jewish sector of the UN plan—but often reached beyond settlements within the demarcated Jewish state to secure strategic terrain and launch themselves for the declaration of an independent state of Israel.

Theoretically, Resolution 181 was to establish peace through partition. In practice, it was to serve as the legal and political rationale for one of the most profound displacements of population in modern history. The Palestinians were not consulted on the partition of their country, and their refusal was characterized by international powers as intransigence rather than opposition to a colonial partition of their nation.

As Khalidi points out, the chain from the Balfour Declaration to the UN Partition Plan discloses a familiar pattern: Palestinian voices were systematically excluded from decisions about their own future, while external powers oscillated between imperial calculation and international diplomacy in order to consecrate Zionist claims.9

The year 1947–1948 was not just the collapse of a mandate or the outbreak of war. It was the peak of a broader historical movement, precipitated by a letter in the context of World War I and shaped by international institutions that acted in the interest of diplomacy rather than justice. To the families who had fled their homes early in 1948, artillery was not just a war description—it was the final output of London, Geneva, and New York decisions made months ago, prior to firing a single bullet.

During April and May 1948, a series of operations were mounted by Zionist forces—Operations Nachshon, Harel, and Yiftach—against towns such as Haifa, Jaffa, Tiberias, and numerous smaller villages. These operations were swift, well-planned, and merciless. In Haifa, panic broke out as Haganah troops used mortars to shell Arab quarters, driving thousands towards the port, where British ships took them away—most for good.11

Jaffa, a prosperous port city and economic hub, also suffered. Open to intensive bombing and psychological warfare—threats shouted over blaring loudspeakers—tens of thousands of Palestinians panicked and fled. Some died trying to escape by sea; others were killed on the streets. Avi Shlaim points out that the expulsion of Palestinians from Jaffa was not an accident but a policy aimed at taking possession of land before the creation of the Israeli state.12

Not all expulsions were carried out by open force. In some cases, threats of a massacre, like that at Deir Yassin, where over 100 villagers—many women and children—were murdered by the Irgun and Lehi, were enough to induce flight en masse.13 The psychological harm of these occurrences was incalculable. Villagers fled in convoys, leaving behind livestock hitched to trees and doors left open behind them.

International monitors began paying serious attention. British reporters, UN officials, and Arab politicians began issuing alerts of a human catastrophe in progress. Appeals to the world were only enough to slow the parade. Arab countries condemned the expulsions as ethnic cleansing according to UN General Assembly records, calling out the new, building Israeli state on its failure to respect the letter of the spirit of the UN Partition Plan.15

By the time the British mandate officially ended on May 14, and Israel declared independence, over 200,000 Palestinians had already been displaced—a number that would grow over three times larger by the end of the war.16 Roads were filled with endless columns of refugees: families on foot, donkeys carrying household goods, babies wrapped in cloth and held under the sun. Many hoped to return once the fighting stopped. Most did not.

The spring of 1948 was not only a period of war—it was a period of irrevocable transformation. While Plan Dalet unfolded on the battlefield, entire Palestinian cities began to disintegrate. Not gradually, and not accidentally. They were carefully planned military campaigns, followed by an increasing awareness that Palestinians were not just being attacked—they were vanishing.

Two of the most symbolic and strategic losses were Haifa and Jaffa. In Haifa, where tens of thousands of Palestinians were living, the Haganah launched a well-coordinated attack in the latter half of April. A torrent of mortar shells rained down on Arab neighborhoods, sending jolts of panic among the civilians. As fighting grew more intense, British authorities, still under the final days of the Mandate, asked Arab residents to leave. Thousands fled to the seaport in a matter of hours, commandeering British vessels that carried them off to Lebanon and other Arab nations—most believing, in vain, that they would return in a few weeks.

Jaffa, a prosperous Arab cultural and economic center located on the coast, was next to fall. As Avi Shlaim reports, the capture of Jaffa was no accident—it was planned. Zionist militia groups from the Irgun deployed bombs and propaganda leaflets into the city, urging inhabitants to leave. The intention was to clear the ground for Tel Aviv’s growth and to ensure Jewish control of the coast.17 Jaffa was deserted by tens of thousands in desperation, abandoning shops, schools, and family homes.

However, even more significant than war successes was the Deir Yassin massacre that shattered the psychological resilience of Palestinian society. On April 9, 1948, over 100 men, women, and children were killed by Zionist paramilitary groups Irgun and Lehi in a small village just outside Jerusalem. The attack was vicious—some were killed inside their homes, others after surrendering. Rashid Khalidi presents Deir Yassin not as an isolated massacre but as part of a pattern of a broad policy to terrorize and empty.18

News of the massacre spread quickly. Village residents across the country, with fear of their turn next, began to flee ahead of time. The term Nakba—disaster—had not yet entered the vocabulary of the world, but already it was out on the ground being lived.

By the time Israel formally declared independence on May 14, 1948, the scale of displacement was unimaginable. Over 200,000 Palestinians had already disappeared from their homes, either by flight or by forced exile. At war’s end, that would reach over 700,000, to create one of the greatest refugee crises of modern Middle Eastern history. Families spent days in a row on foot, carried children through mountains, and trudged through rivers under gunfire. Most fled to nearby states—Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Egypt, and the West Bank—where they were embraced by temporary camps that would later coalesce into permanent exile.

The humanitarian crisis was serious. Refugees were left with only the clothes on their backs. There was a lack of food, irregular water, and disease spread within overcrowded camps. Red Cross and later UNRWA (United Nations Relief and Works Agency) relief work was understaffed and swamped. Medical care and sanitation were sparse in camps. Refugees in many places were treated not as human beings in need of justice but as political nuisances.

At the United Nations, Arab states condemned what had taken place at Haifa, Jaffa, and Deir Yassin. The leadership of Israel was blamed for violating the Partition Plan and systematic ethnic cleansing. General Assembly reports later in 1948 show Arab representatives pleading for foreign intervention and warning that the refugee crisis was not just a disaster—it was a threat to Middle Eastern security.

The displacement of 1948 was not sealed with flight—it was the beginning of an exile that would persist for decades. What began as a mass eviction soon became one of the world’s longest-running refugee crises. Those who left with keys in hand and hopes of return were suspended in limbo across borders and generations.

The systematic erasure of Palestinian existence reshaped not just a map, but a national identity. International debates over legal rights and return have raged for over 75 years, but justice remains elusive. What was seized in 1948 was something more than territory—it was the future of a nation, suspended between memory and the ongoing struggle for self-determination.

- Ilan Pappé, The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine (Oxford: Oneworld Publications, 2007), 119. ↵

- Benny Morris, 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008), 166. ↵

- Rashid Khalidi, The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine: A History of Settler Colonialism and Resistance, 1917–2017 (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2020), 38. ↵

- “The Balfour Declaration,” The Avalon Project, Yale Law School. Accessed April 10, 2025. https://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/balfour.asp. ↵

- Rashid Khalidi, The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine: A History of Settler Colonialism and Resistance, 1917–2017 (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2020), 29. ↵

- Rashid Khalidi, The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine: A History of Settler Colonialism and Resistance, 1917–2017 (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2020), 8. ↵

- BADIL Resource Center for Palestinian Residency and Refugee Rights, Briefing Note – 29 November 1947: UN Palestine Partition Plan. Accessed April 10, 2025. https://badil.org/phocadownload/Badil_docs/Working_Papers/BADIL-Briefing-Note-Partition-Plan.pdf. ↵

- Arab Higher Committee. “Letter to the Secretary-General on the Partition of Palestine.” United Nations, October 2, 1947. Accessed April 12, 2025. https://www.un.org/unispal/document/auto-insert-212035/. ↵

- Rashid Khalidi, The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine: A History of Settler Colonialism and Resistance, 1917–2017 (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2020), 61. ↵

- Ilan Pappé, The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine (Oxford: Oneworld Publications, 2007), 118. ↵

- Benny Morris, 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008), 78. ↵

- Avi Shlaim, The Iron Wall : Israel and the Arab World (London : Penguin, 2001), http://archive.org/details/ironwallisraelar0000shla_p1n8. ↵

- Ilan Pappé, The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine (Oxford: Oneworld Publications, 2007), 119. ↵

- Benny Morris, 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008), 166, 167, 168. ↵

- United Nations. “General Assembly – Question of Palestine.” Accessed March 13, 2025. https://www.un.org/unispal/data-collection/general-assembly/. ↵

- Institute for Palestine Studies. “The Nakba.” Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question – Palquest. Accessed March 13, 2025. https://www.palquest.org/en/highlight/160/nakba. ↵

- Avi Shlaim, The Iron Wall : Israel and the Arab World (London : Penguin, 2001), http://archive.org/details/ironwallisraelar0000shla_p1n8. ↵

- Rashid Khalidi, The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine: A History of Settler Colonialism and Resistance, 1917–2017 (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2020), 84. ↵

3 comments

Micaella Sanchez

Hearing about this story puts it into perspective about the people and families fleeing their homes in 1948, carrying only keys, bread, and hope. The scale of the Nakba was not just a historical fact—it was a human tragedy, repeated across generations. As I learned about Plan Dalet and the violence in places like Deir Yassin and Jaffa, I understand the lasting weight of displacement and the struggle for justice; even today, it is happening all over the world. Great job on this article.

TJ

The article paints a vivid picture of how ordinary life in Palestinian villages ended in chaos and fear in 1948. The author’s use of personal details like families waking to explosions and people fleeing with only a few belongings brings the human cost into sharp focus. I also found the historical overview from the Balfour Declaration through Plan Dalet helpful for understanding why so many Palestinians were forced from their homes. The balance of firsthand accounts and scholarly sources made the story both moving and informative.

Carlos Flores

This is an incredibly powerful and well-researched piece. The way you weave together historical context with vivid, human-centered storytelling makes the history of the Nakba deeply personal and immediate. Your attention to detail, use of strong sources, and clear compassion for the people affected create a narrative that is both heartbreaking and essential. Truly outstanding work—thank you for writing this.