David Crockett was a man with a plethora of unique skills and talents. He was a congressman, politician, frontiersman, soldier, and also a prolific storyteller. Crockett wanted to begin a somewhat new life in 1835 right after he lost his final bid for Congress. So he had a desire to leave for Texas. Crockett was uncertain about what he wanted for himself or what was next for himself in life. On October 31, 1835, Crockett left Tennessee and ventured to Texas. Crockett set out west to a new place filled with tension. He soon found his true purpose in life in San Antonio de Béxar. Before leaving from Tennessee to Texas, Crockett went to a political meeting composed of his constituents and said “I told them, moreover, of my services, pretty straight up and down, for a man may be allowed to speak on such subjects when others are about to forget them; and I also told them of the manner in which I had been knocked down and dragged out, and that I did not consider it a fair fight; anyhow, they could fix it. I put the ingredients in the cup pretty strong I tell you, and I concluded my speech by telling them that I was done with politics for the present, and that they might all go to hell, and I would go to Texas.” He demonstrated his ambition to leave for Texas and his time of being a politician was over.1

Crockett had a long journey ahead for him to travel from Tennessee to Texas. He left his wife, children, and his home behind when he traveled to Texas. Three other men also joined Crockett in his expedition west to Texas. The path to Texas was physically demanding and formidable. They started down the Mississippi River to the Arkansas River, and then up the river to Little Rock. At Little Rock, the three other men decide to turn back to go home because they determined that the journey ahead was not worth the effort. They were not as determined as Crockett was to reach Texas. After the men decided to turn back and leave Crockett to travel on his own, Crockett then went on to Fulton, Arkansas. This is where Crockett reached the northern boundary of Texas. He then crossed the river to Clarksville, and he finally crossed the Red River to Nacogdoches.2

Crockett’s adventure to Texas had come to an end, and he safely made it to Nacogdoches, Texas. Crockett’s tenacity and persistence are what drove him to continue his journey once the other three men decided to turn around at Little Rock. Crockett was ambitious to find a new life in Texas, and the travel to Texas tested him to find out how much he truly wanted a fresh start. He arrived in Nacogdoches in early January of 1836.3

Now in Nacogdoches, Crockett began to find a sense of community when he and sixty-five other men signed an oath to the Provisional Government of Texas for six months. He signed his full allegiance to the Provisional Government of Texas. Each man that signed the oath to the Provisional Government of Texas was compensated with 4,600 acres of land as payment for their service. Crockett became a part of the Texas army, which was coming together to accomplish a common goal: to fight for full independence from Mexico. Crockett had now found a new purpose for himself in life.4

Crockett made himself a part of something bigger than himself with the Texas Army. Crockett and five other men rode out to San Antonio de Béxar on February 6, 1836. Once the five men, including Crockett, reached San Antonio de Béxar, they camped just outside of the town. Shortly after, they were approached by James Bowie and Antonio Menchacha. They were later taken to Don Erasmo Sequin’s home.5

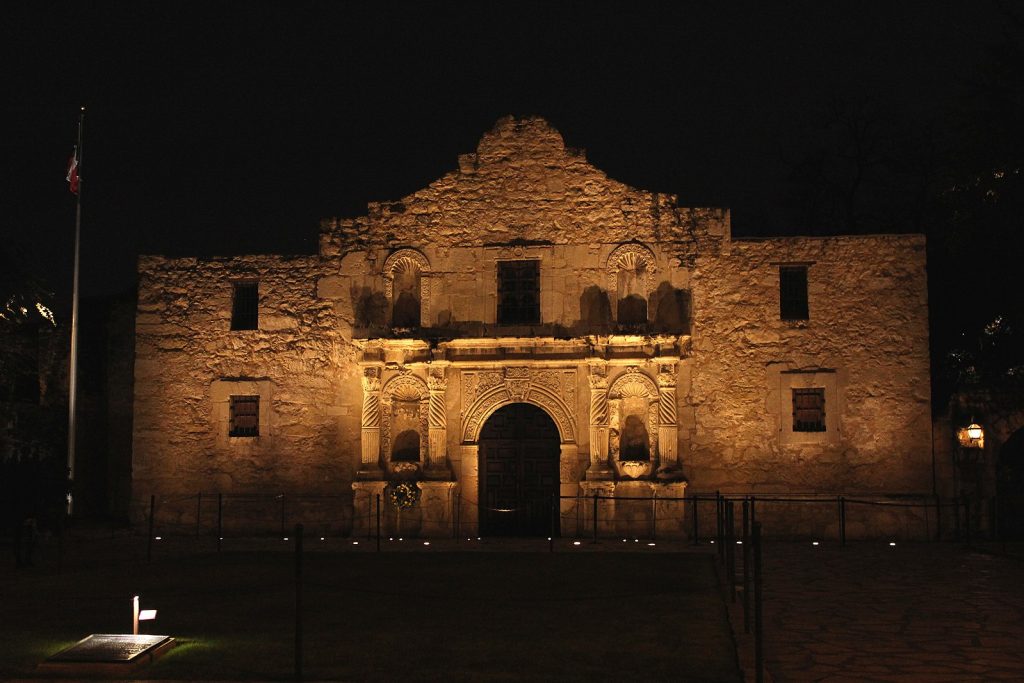

William Barret Travis arrived at the Alamo on February 3, 1836, with a compact cavalry company. Jim Bowie also assumed joint command of the troops with William B. Travis. A couple of days passed by, and Crockett and his Tennessee volunteers rode into town with long rifles hung over their shoulders. As the days went by, the Mexican army advanced towards San Antonio de Béxar.6 General Antonio López de Santa Anna and his army began to march north to head to Texas. The goal for him and his army was to re-capture the city of San Antonio de Béxar and to finally end the Texas Revolution. General Santa Anna and his army finally arrived at San Antonio de Béxar on February 23, 1836. They arrived with the goal of recapturing the city. General Santa Anna had no knowledge of the Texans and the determination they had to fight for independence. The arrival of the Mexican army cued the Texan defenders, including Crockett, to enter the Alamo. The Alamo was heavily fortified once the Texan army heard the Mexican army has reached the city of San Antonio de Béxar. James Bowie called a parlay once the Mexican army arrived at the city of San Antonio of Béxar. Then Greene B. Jameson met with the Mexican officials. General Santa Anna demanded that he and the rest of the Texans inside the Alamo surrender at once. General Santa Anna would decide their future if the Texan army decided to surrender. William B. Travis responded to the demands from Santa Anna with a cannon shot. The retaliation from the Texan army started the siege of the Alamo. General Santa Anna ordered that a red flag was to be flown from the San Fernando Church representing no mercy, even if they surrender.7

Colonel William Travis took full command of the Alamo on the first day of the siege because Jim Bowie suffered from lung disease. Jim Bowie was unable to continue as the commander of the Alamo due to his illness and was unable to maintain his power of command. The Alamo was continually hit with cannon blasts from the Mexican army and the army gradually moved their artillery closer to the walls of the Alamo. There was a perimeter of 440-yards for the Texan defenders to defend at their posts, but the Texans did not have enough men to rotate duty. The lack of manpower allowed the Mexican army to gradually move their men and artillery forward towards the walls of the Alamo. The Texan defenders hoped for reinforcements to come to aid in their almost impossible task of defeating the Mexican army while being severely outnumbered.8

On the morning of March 1, 1836, a group of thirty-two men from Gonzales managed to sneak through enemy lines. A Texan sentry spotted movement below at the gates of the Alamo and fired his rifle assuming it was a soldier from the Mexican army that was attempting to break into the Alamo. The sentry shot one of the men in the foot, and the man who was shot let out a scream due to the pain of being shot in the foot by a rifle. The sentry soon realized his mistake, and he called for the gates to be opened to allow the thirty-two men to be let into the Alamo. Once they were inside the fortress, they were greeted. David Crockett played his fiddle to honor and welcomed the new men who had come to help the cause to defend the Alamo and for independence. The men inside of the Alamo had high spirits and felt luck was now on their side, due to the new men who had come from Gonzales. Just two days later, William Travis had received news that 400 men would not be coming to help the men inside of the Alamo. The men inside of the Alamo, including David Crockett, had been tasked with what seemed to appear as an impossible task. Nevertheless, the Alamo defenders did not surrender or die without attempting to defend the Alamo.9

General Antonio López de Santa Anna had grown tired and became impatient with the standoff with the Alamo defenders on March 5, 1836. William Travis sensed an attack was coming from the Mexican army. He gathered all 189 of the men inside of the Alamo to ask if any of them wanted to flee the Alamo and escape with their lives. One man chose to leave the Alamo, and it was Frenchman Louis Rose who chose to leave. The evening of March 5, the Mexican Army ceased shell fire for the first time in twelve days. The men inside the Alamo were fatigued and slept on the ground now because there was less noise due to the shellfire from the Mexican army. The Alamo defenders still clutched their weapons as they slept that night. They were prepared for an attack if the Mexican army chose to use the element of surprise from the night.10 On the morning of March 6, the Mexican soldiers began to assume their battle positions in the dark before dawn. General Antonio López de Santa Anna gave an order for the soldiers to advance at 5:30am. Four columns of men began their quiet march to the Alamo to give them the element of surprise as they gradually progressed towards the Alamo. The moonlight cast a faint light across the plain of battle, and the Mexican army under General Santa Anna was composed of 1,800 soldiers. While the Mexican army advanced, an excited soldier of the Mexican army screamed “Viva Santa Anna!” and “Viva Mexico!”11 The other soldiers in the Mexican army began to take up the cry and their screams were heard by the Alamo sentries. The Alamo sentries then quickly jumped up and screamed to their fellow soldiers to prepare themselves for battle. There was wave after wave of Mexican soldiers who kept coming towards the ten-foot-high stone walls that fully surrounded the Alamo. The Mexican army raised ladders and began to climb the walls of the Alamo. In the heat of battle, David Crockett and his Tennessee volunteers did not shy away. Crockett and his Tennessee volunteers picked up their long rifles and started to fire down on the Mexican army. One of the first men to fall in battle was William Barret Travis who took a single bullet and was mortally wounded. He was the commander of the Alamo forces.

Several Mexican soldiers managed to climb the north wall because they used the ladders. Once they were inside, they quickly ran to a nearby gate and opened it for their fellow Mexican soldiers. The opening of the nearby gate allowed the Mexican army to storm into the Alamo. At this point, the Texans were forced to desert the north wall. The Texans continued to shoot at the waves of Mexican soldiers. Soon after, the south wall has also been breached by waves of Mexican soldiers. The Alamo was flooded with the enemy. The Alamo defenders now were forced to engage in hand-to-hand combat, and also use bayonets. Hundreds of Mexican soldiers stormed the Alamo, and the Alamo defenders retreated into the long barracks building. The Texans closed the doors behind them with Mexican soldiers outside.12 Now, the Alamo defenders were locked inside, and the Mexican soldiers turned the Alamo’s cannons towards the doors the Texans hid behind and fired the doors off their hinges.

David Crockett and a few other Texan soldiers were in the roofless old church when Mexican soldiers stormed through the doors. There was not enough time for Crockett to load his rifle, and he then raised “Old Betsy” and began to swing his rifle as a club. Crockett and six other men fought until these seven men were the last Texans still alive. Many discrepancies arise when it comes to the way David Crockett died at the Alamo. There are sources to suggest that Crockett and the six other men were taken as prisoners. Santa Anna soon ordered for their executions. The Mexican soldiers drew out their swords and hacked to death the last of the Alamo defenders, marking the defeat of the Texans at the Alamo and the victory of the Mexican army under General Antonio López de Santa Anna. All of the 189 Alamo defenders were killed on March 6, 1836. General Santa Anna later gave an order to collect wood so they could burn the Texans’ bodies. At 5pm, a torch was lit and was put up to the massive funeral pyre that had been constructed in the courtyard north of the capital. The smell of the burned flesh and smoke filled the air of the small town of San Antonio de Béxar. Only fifteen women and children, along with one male slave left the Alamo and survived. They were released and spared by General Santa Anna.13

General Santa Anna and his Mexican army left San Antonio de Béxar feeling victorious after successfully defeating all 189 Alamo defenders. Shortly after the battle of the Alamo, on April 21, 1836, the Battle of San Jacinto occurred. The Texans were victorious in this battle. After the Alamo, “Remember the Alamo!” became their rallying cry during the Battle of San Jacinto. The Texan forces were led by Sam Houston at the Battle of San Jacinto. Texas won its independence from Mexico, which brought the revolution to a close. On March 2, 1836, Texas formally declared its independence from Mexico. The Alamo became a symbol of their relentless resistance to oppression and their goal of independence from Mexico. The most famous monument to David Crockett is located in Ozona, Texas. David Crockett is remembered as a brave and heroic man along with the other 188 men that fought alongside Crockett and laid down their lives for a greater cause. Every man who died fighting that day will be forever remembered in history as brave and valiant soldiers. David Crockett and the rest of the Alamo defenders may not have won on March 6, 1836, but they were a part of an effort that was soon to be successful. It is unfortunate to read that the Alamo defenders never had the chance to know that their sacrifice was not in vain, and Texas received independence. In a way, Crockett and the Alamo defenders were victorious in the end.14

- John Stevens Cabot Abbott, David Crockett: His Life and Adventures (Forgotten Books, 2005), 295. ↵

- John Stevens Cabot Abbott, David Crockett: His Life and Adventures (Forgotten Books, 2005), 298-309. ↵

- John Stevens Cabot Abbott, David Crockett: His Life and Adventures (Forgotten Books, 2005), 338. ↵

- Encyclopedia of the Alamo and the Texas Revolution, 2007, s.v. “Crockett, David (August 17,1786-March 6, 1836),” by Thom Hatch. ↵

- Encyclopedia of the Alamo and the Texas Revolution, 2007, s.v. “Crockett, David (August 17,1786-March 6, 1836),” by Thom Hatch. ↵

- Carmen Bredeson, The Battle of the Alamo: The Fight for Texas Territory, Spotlight on American History (Brookfield, Conn: Lerner Publishing Group, 1996), 30. ↵

- Carmen Bredeson, The Battle of the Alamo: The Fight for Texas Territory, Spotlight on American History (Brookfield, Conn: Lerner Publishing Group, 1996), 32. ↵

- Carmen Bredeson, The Battle of the Alamo: The Fight for Texas Territory, Spotlight on American History (Brookfield, Conn: Lerner Publishing Group, 1996), 35. ↵

- Carmen Bredeson, The Battle of the Alamo: The Fight for Texas Territory, Spotlight on American History (Brookfield, Conn: Lerner Publishing Group, 1996), 36. ↵

- Carmen Bredeson, The Battle of the Alamo: The Fight for Texas Territory, Spotlight on American History (Brookfield, Conn: Lerner Publishing Group, 1996), 37. ↵

- Carmen Bredeson, The Battle of the Alamo: The Fight for Texas Territory, Spotlight on American History (Brookfield, Conn: Lerner Publishing Group, 1996), 9. ↵

- Carmen Bredeson, The Battle of the Alamo: The Fight for Texas Territory, Spotlight on American History (Brookfield, Conn: Lerner Publishing Group, 1996), 10. ↵

- Carmen Bredeson, The Battle of the Alamo: The Fight for Texas Territory, Spotlight on American History (Brookfield, Conn: Lerner Publishing Group, 1996), 11-12. ↵

- Encyclopedia of the Alamo and the Texas Revolution, 2007, s.v. “Crockett, David (August 17,1786-March 6, 1836),” by Thom Hatch. ↵

3 comments

Melyna Martinez

This article shows an interesting point of view of David Crockett and the battle of the Alamo. I never knew there was more to Crokett than being in the Texan Army, he had others around that affect greatly in the independence of Texas. It is so interesting to see that this battle was not what won the independence of Texas but created that path to make it happen.

Bruce Eubank

Very nice article. Well written.

Carlos Hinojosa

I always thought the story of the Alamo was the definition of someone dying for a cause they believed in. I think that for all the soldiers that died in Alamo, but I think Davy Crockett was the personification of that. I heard many versions of his death and the last seven but the one I like to think what happened was that they all fought until they drew their last breath. SO, a last stand, I think that because it just sounds cooler and more believable. A very good article, hope to read more by you.