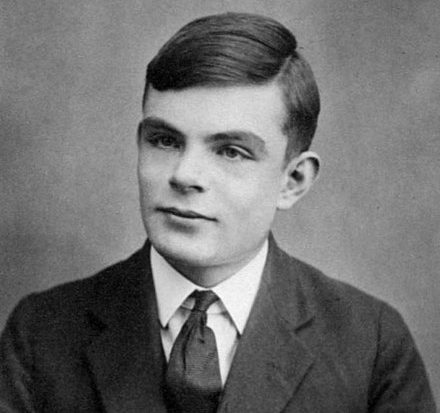

The dark cloud of war was glooming over Britain in the year 1939; Germany had recently begun its assault on Poland after Hitler and Stalin had signed their non-aggression pact, dividing Poland between them, as Hitler continued his rise to power.1 In 1940, the war theater turned to France as Germany attacked it with full force. Although France put up a fight against those German forces, Germany’s war strategy and new developed technology got the best of the French. The new technology of the Germans included something called the Enigma Code, which was a typewriter-looking machine that consisted of rotating wheels, usually three of them, that were all wired differently. Enigma was used at a certain time of day to send out coordinates for German attacks on Britain shipments via U-boats.2 But even before the war had started in September 1939, the British were already trying to decipher the Enigma machine, and to do so, they had enlisted the help of mathematics genius and cryptographer, Alan M. Turing, to help defeat the new threat of Enigma.

Well before the conflict of World War II erupted in Europe, in 1931, Alan Turing was an ordinary English undergraduate student, who was set on finishing his years at King College at Cambridge as a mathematics major. Throughout his years as an undergraduate, as well as throughout his childhood, mathematics seemed to be a natural talent for Turing. What also came naturally to Turing was his ability to conceive his own mathematical ideas while remaining oblivious of the published literature that was provided to him in his classes.3 Turing had a strong passion for seeking new knowledge to improve himself and his competence. A mathematical problem that Turing aimed to solve was called the Entscheidungsproblem, also known as the Decision Problem, which was a set of rules that was followed when making calculations. The “Decision Problem” takes these statements and puts axioms, or principles, onto itself and says, “yes” or “no” to determine whether the axiom is true. Unfortunately, Turing concluded that the Entscheidungsproblem was unsolvable, but at Princeton University in the United States, the American logician Alonzo Church had just finished his argument for publication on April 12, 1936, concluding that there is no way to solve this problem.4 At the same time, in 1936, Alan Turing published his seminal paper “On Computable Numbers, with an application to the Entscheidungsproblem.”5 Church’s discovery had made its way to England and caught the eyes of young Alan Turing. Turing, astonished by his work, then traveled to the United States to expand his knowledge by studying under Church’s mentorship at Princeton.

After arriving at Princeton, Turing went straight to work on his graduate studies while working with Alonzo Church. But Church did not know that Turing had crossed the sea with a different view of “The Decision Problem.” This new view would be called the “Automatic Machine,” or what came to be called, the “Turing Machine.” The Turing machine is used for the input of mathematical codes, into a memory system to which then we can control data. Through this we can take one equation, store it in the system’s memory, and then run that equation on an infinite loop until it comes out with an exact answer.6 Alan’s newest invention would later be known as the foundation of computer science, but it was also an invention that would become a major contribution in World War II.

Right before Britain entered World War II, Turing went back home to England, and he was asked by the British government to help in an operation to decipher German coding, the Enigma. With Germany’s invasion of Poland in September 1939, Britain and France concluded that military action was the only way to stop Germany’s aggression. Not only was Turing and his new team, Hut 8, a British encryption group, in charge of cracking the Enigma, they were also responsible for reading U-boat signals that had been attacking the British shipments.7 U-boats played an important part in World War II because Britain, the United States, and Japan used the sea for communication, as well as to send out shipments to their allies.8 Germany took full advantage of this, preventing shipments getting to Britain, while also limiting their communication with allied forces. While the U-boats were also stealthy, these attacks continued to remain oblivious to Britain because of the Enigma. The Enigma was introduced in 1918 by German electrical engineer, Arthur Scherbius, who patented this cryptographic technology. In the year 1926, the German navy adopted Enigma, and fortified the machine for warlike purpose, which in turn were to be put to use to launch attacks using specific coordinates through the coding it produced.9 The Enigma machine was a typewriter-looking machine that was composed of letters “A-Z,” and in front of the board were three rotors that spun every time a letter was pushed. When each letter was pushed, a letter that was not itself, which was also determined by the plugboard, would come up and display something different. For example, if we typed out ‘TURING,’ the encryption that Enigma would produce would be something like ‘VNQOPA.’ And the receiver of the code would need an Enigma devise to decrypt the message in reversing the process.10

The Enigma was seen as a big threat that Germany wielded during the beginning of the World War. In fact, with the combinations that the Enigma could create, there were about 158 trillion possible combinations with every message that was sent.11 Turing and his team were successful on intercepting messages from the German Enigma machines, but could not decipher them because they changed every twenty-four hours. This posed a bigger threat, not only to Turing and Hut 8, but to Britain as well, if the code was not broken quick enough. Turing knew that in order to effectively crack the incoming Enigma transmissions, this type of deciphering could not be done by hand. Turing had began to put together patterns for Enigma that could be solved not by hand, but by machine. Prior to Turing’s entrance into Hut 8, his Polish teammates had tried to develop a machine called the “Bomba,” that could select a combination from Enigma on that specific day, but they had ultimately failed. Turing had then gone to travel to France in 1940, before their fall, to meet with PC Bruno, the Polish/French intelligence station in Paris to gather intel. Unfortunately, Turing had found nothing that would help lead to deciphering Enigma. Turing had come to write what is called, “The Profs Book,” which is a 152-page written document that tells us how the encrypting machine should be broken up. He then came to realize that the codes being sent out could be broken into larger and larger increments and that you could also take the small portions of code and solve those by hand.12

Through the trial and error of trying to decipher codes, Turing had used his intelligence to come up with an electromechanical machine called “The Bombe.” Essentially, the Bombe was a giant machine that had 108 rotating drums that spun through thousands of times to replicate the movements of the rotors that were on the Enigma, performing different decrypting patterns beyond the human capacity.13 The Bombe also had the capability of imitating thirty-six Enigma machines simultaneously.14 Germany had suspected that someone was trying to crack their code, so everyday, they changed the combination of letters in the rotors and eventually added an extra rotor to increase the complexity of the code. With the extra rotor added, this added to the number of combinations that went through the Enigma’s algorithm and made it more difficult for Turing and his team to crack. What Germany did not know was that when they sent out their Enigma codes to the U-boats, they would also include the weather report, and a little bit of the coordinates. Turing and Hut 8 worked tirelessly to crack the changing codes, using little bits of known German to decrypt slight pieces of Enigma. “In March, 1941, intelligence analysts drew the connection between an Italian naval transmission,” enabling the allied forces to input accurate combinations into the “Bombe.”15 In this situation, we can thank Italy for the cracking of Enigma because their Enigma machine was lacking a plugboard, minimizing the amount of combinations that was produced. Italy’s faulty version of the Enigma was the cause of Turing’s big success in cracking the Enigma. With Turing’s newfound discovery, Hut 8 was now able to track down German attacks on British supply shipments. Germany had remained under the assumption that their codes were being broken, but their confidence in their new developed engineering got the best of them.15 With Turing’s use of the “Bombe,” this intelligence put Turing a step ahead of Germany’s forces, giving the Allied forces the location of German intentions, plans, locations, and movements at every turn.17

With the success of Turing’s “Bombe” and the cracking of the Enigma, his invention began to expand across all of Britain, as well as the other allied nations. Turing’s accomplishment would eventually lead to the production of 121 Bombes that were used for fighting against attacks, putting the allied forces in a path towards victory.18 Alan Turing played a crucial role in the Second World War. Historians speculate whether his accomplishments shortened the war by as much as two years. Little did Turing know that this invention had saved about two million British lives, more lives than any other British hero. Turing would then be known as the founder of artificial technology, responsible for much of our modern-day technology.

Unfortunately, Turing’s life had come to a close at young age. Turing was an opened homosexual, but before 1967, being a homosexual in Britain was illegal and you were charged with “gross indecency” if found guilty. Alan was faced with the choice of imprisonment or probation. After Turing chose probation, he had to undergo chemical castration, where they injected estrogen, a female hormone, into Turing, believing that would cure his homosexuality. Though the estrogen did decrease his libido, another side effect was that of depression. After facing his newfound struggles, Turing could not handle his own life anymore and ended it himself with a cyanide-laced apple. Even with the accomplishments and breakthroughs Turing had done, not only for Britain, but the world, he was treated horribly in the end. In 2013, Queen Elizabeth had royally pardoned Turing from his “gross indecency” and from then on Alan Turing has then been recognized as a very important figure in science, engineering, mathematics, and computer science.

- Gale Encyclopedia of US History: War, 2008, s.v., “World War II (1939-1945),” Gale eBooks, 5. ↵

- Algis Valiunas, “Turing and the Uncomputable,” The New Atlantis, no. 61 (2020): (58). ↵

- Algis Valiunas, “Turing and the Uncomputable,” The New Atlantis, no. 61 (2020): 50. ↵

- Andrew Hodges, Alan Turing: The Enigma: The Book that Inspired the Film Imitation Game Updated Edition (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014), 141. ↵

- Steven G. Krantz, Episode History of Mathematics (Washington D.C.: Mathematical Association of America, 2010), 345. ↵

- Steven G. Krantz, Episode History of Mathematics (Washington D.C.: Mathematical Association of America, 2010), 346. ↵

- Encyclopedia of Science, Technology, and Ethics, 2005, s.v. “Turing, Alan,” by Andrew P. Hodges. ↵

- Kathleen Broome Williams, Submarines: Did Submarines Play an Important Role in World War II? (Detroit, MI: St. James Press, 2000), 256. ↵

- Algis Valiunas, “Turing and the Uncomputable,” The New Atlantis, no. 61 (2020): 57. ↵

- Andrew Hodges, Alan Turing: The Enigma: The Book that Inspired the Film Imitation Game Updated Edition (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014), 206. ↵

- Andrew J. Avery, All the King’s Men: British Codebreaking Operations: 1938-43 (East Tennessee State University, 2015), 3. ↵

- Andrew J. Avery, All the King’s Men: British Codebreaking Operations: 1938-43 (East Tennessee State University, 2015), 63-64. ↵

- Chris McNab, “Bombe Versus Enigma,” The Quarterly Journal of Military History, no. 1 (2015): 17. ↵

- Chris McNab, “Bombe Versus Enigma,” The Quarterly Journal of Military History, no. 1 (2015): 17. ↵

- Algis Valiunas, “Turing and the Uncomputable,” The New Atlantis, no. 61 (2020): 64. ↵

- Algis Valiunas, “Turing and the Uncomputable,” The New Atlantis, no. 61 (2020): 64. ↵

- Chris McNab, “Bombe Versus Enigma,” The Quarterly Journal of Military History, no. 1 (2015): 17. ↵

- In Encyclopedia of Espionage, Intelligence and Security, 2005, s.v., “Bombe,” Adrienne Wilmoth Lerner, 138. ↵

22 comments

Trenton Boudreaux

It’s depressing to know that in homophobic 1940s-60s Britain, not even someone who possibly saved millions of lives was immune from the charges of “gross indecency.” I never knew that Turing was a homosexual, and it is a real shame that such a minor character trait would be used against him. At least now, Turing is remembered as a hero and not as a degenerate.

Mia Gonzales

Nathan, your writing on Alan Turing provided an apt introduction in the depth and importance of his work throughout World War II. Without his impressive work and strive in the field of mathematics, the war would have ended much differently for the Allies and two million more lives would have been added to the final death toll. Additionally, as an openly gay man in a time where expressing yourself and who you loved could be found illegal, Turing served and continues to serve as a role model to LGBT+ youth and peers.

Monserrat Garcia

I had not known anything about Alan Turing until I was in middle school and the Imitation Game with Benedict Cumberbatch came out. I watched it purely because Benedict came out in it but ended up being fascinated by this historical figure so when I saw your article I was automatically in awe. Alan Turing and Hut 8 should be more known in history but unfortunately aren’t. Alan Turing’s life is also very symbolic because he was a hero but treated as a villain simply because he was homosexual. It is very interesting to see how as time goes on people realize that what used to be looked down upon should not have been.

Soleil Armijo

I absolutely love this story! It’s one of my favorite stories to come out of WW II, I remember when I saw the movie the pride I felt in being human and the amazing things we can do. It’s so interesting how a couple of letters and numbers can make a code, and it’s even more interesting that there are those who without any knowledge can decipher those codes.Truly mind-blowing! I am deeply sadden though about the end of his life. It was a sad reality in those times, and I find the terms of his probation cruel especially after the great work he did.

Paula Salinas Gonzalez

I had already heard of Alan Turing but I didn’t know much of his life in detail. This article was super informative with how many things he was able to achieve although it was a very sad ending. His knowledge is truly impressive and it’s disappointing how he didn’t get the respect he deserved after saving so many lives.

Alvaro Garza

The Bombe is a very complicated machine and a complicated concept to explain, but you did well! I had read about the Bombe Machine in the past but got confused and gave up with only a partial understanding. Your explanation helped me wrap my head around the concept completely. Coding and code breaking is an interesting topic to me so this made for a really entertaining read!

Ian Mcewen

intelligence is always important when fight against some one be it physically or through other ways. by having a code that was near impossible to crack the Germans could conduct operations that their enemies had to idea about which lead to an advantage in the war. I am interested in that they tried the brute force method which try as much as possible and narrow it down from there.

Nathaniel Tran

I had previously watched the movie on this exact story so now knowing the actual events is very nice. I so surprised that a small story like this in the midst of World War II could have such an impact on it. However, I am sad that the story ends with our hero in disgrace just for being who he is.

Allison Grijalva

I had never read about Alan Turing before but this was a great introduction! It is so sad that his. life was ended due to his sexuality. His invention was so powerful and saved so many people, so to be met with hate was such a sad thing for Turing. Thank you for writing this article!

Marcus Saldana

This article was very well written hitting the highlights of Alan Turning life without missing a beat. The end of his life is a sad way to go after all he has done. Being one of the hero’s of the war and still being seen as villain was to much for him at the end. I am glad that Queen Elizabeth admitted they were wrong even though they cant change the past this was a nice statement.