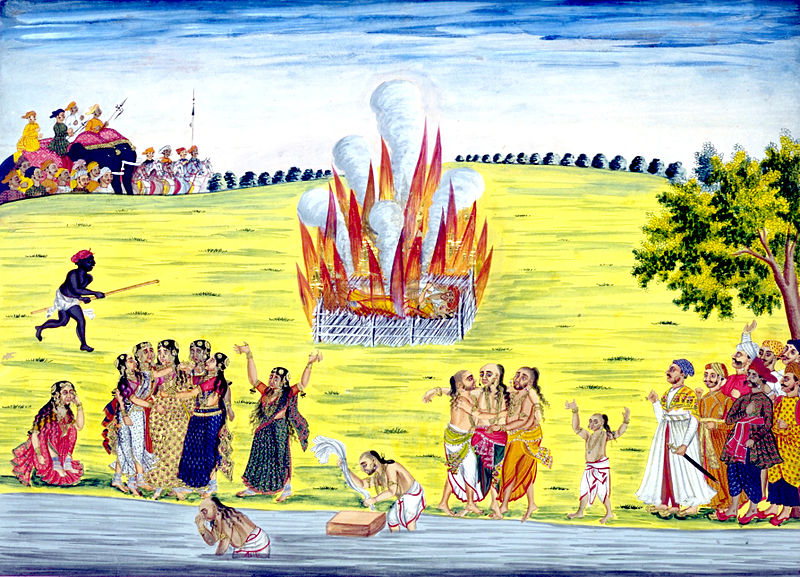

Sati, also known as “Suttee,” was a tradition that was practiced in ancient India from the early centuries BCE to the mid-1990’s. In this tradition, widows were burned at the side of their deceased husbands. There were many reasons behind this tragic form of suicide, but the act was seen as heroic and courageous. The tradition originates with the goddess Sati, who burned herself to death in a fire that she created through her yogic powers, which she obtained after her father had insulted her husband. Sati became an option for women in India who were not “marriageable,” according to social norms. Sati was first recognized in the Mahabharata, one of the two most well-known and important poems of India.1

“LAMP of my life, the lips of Death

Hath blown thee out with their sudden breath;

Naught shall revive thy vanished spark . . .

Love, must I dwell in the living dark?” -Suttee by Sarojini Naidu2

The practice of Sati is recounted by a first century BCE Greek author named Diodorus Siculus. Diodorus mentioned sati stones, which were memorials of all of the wives that have passed along with their husbands. A stone was created for each wife after she gave up her life, and these stones were all collected into a shrine. The earliest memorial that has been discovered dates from 510 BCE.3

Another practice that branched out from sati was the Jahuar, which was a sacrifice of any Muslim woman from the twelfth through the sixteenth century. It was believed that if a woman was burned, she would be safe from rape, which was worse than dying at the hands of a conquering enemy.4

Sati was also practiced by the Brahmans of Bengal, by the system of law from 1100 CE, which was called Dayabhaga. If a woman was widowed, her inheritance would be given to the children of her passed husband. If she were to remarry, her inheritance from her deceased husband would be given to the children and her new husband and her other children would not receive anything. If she passed along with her husband, the inheritance would be given to the children of her dead husband. This law was ended by the Mughal rulers Akbar and his father Humayun in the sixteenth century.5

In 1829, when India was informally ruled by Great Britain, the law to make sati illegal was passed because the act was seen by the British as harsh and cruel to women. Although it was made illegal, there were controversies over whether the sati practice was a religious act, and if so, should that be taken into consideration before prohibiting it.2

In 1987, Roop Kanwar, a woman from the village of Deorala in Rajasthan India, was married to her husband for only eight months before he died. She decided against taking her life in front of thousands of people. Politicians and activists believed that Roop Kanwar was then subsequently drugged by the liquid inside the seeds of an opium poppy flower, and pressured to take her life by those around her. Some people even say that she had super natural powers because her eyes were glowing bright red as she burst into flames. Police concluded that a group of men had been guilty of having drugged her, and they were placed under arrest.7

Sati was a rather harsh tradition, but the significance of these rituals was important to many Indian traditions. The thought of self sacrifice in this way is foreign to Western traditions, and the thought of being burned alive is worse. Sati is now illegal and no longer practiced, but the memories of the dead women from this tradition remain and they will always remind us of this social practice.8

- Kashgar, 2009, s.v. “Life in India: the practice of sati or widow burning,” by Linda Heaphy. ↵

- The Denson Journal of Religion, April 2015, s.v. “Interpreting Sati: the Complex Relationship Between Gender and Power in India,” by Cheyenne Cierpial. ↵

- Dorothy Stein, Burning Widows (University of British Columbia: Pacific Affairs, 1988), 466. ↵

- The Denson Journal of Religion, April 2015, s.v. “Interpreting Sati: the complex Relationship Between gender and Power in India,” by Cheyenne Cierpial. ↵

- Encyclopedia Britannica, March 2015, s.v. “Suttee,” by Wendy Dongiger. ↵

- The Denson Journal of Religion, April 2015, s.v. “Interpreting Sati: the Complex Relationship Between Gender and Power in India,” by Cheyenne Cierpial. ↵

- Encyclopedia Britannica March 2015, s.v. “Suttee,” by Wendy Dongiger. ↵

- Sophia Gilmartin, “The Sati, the Bride and the Widow: Sacrificial Woman in the nineteenth century,” Victorian Literature Vol. 25, No.1 (1997): 142. ↵

99 comments

Mia Stahl

India is known for its laws and traditions that are largely aimed at giving power to upper-class males and taking it away from any females. So the fact that they have a tradition that requires women to burn themselves alive because they no longer have a husband and they are considered unmarriable is not surprising. It also shows that it was so difficult to exist as a woman in ancient India that death seemed more suitable than life with out a husband.

Kristy Feather

This article calls Sati a “Suicide” so does this mean that the widows were provided the opportunity to say no? In my personal opinion, to have that sort of dedication to someone is both ludacris but also impressive at the same time. In many religions, spouses would be united in death so it simply made more sense if someone were to die with each other rather than complicate death by remarrying. This article makes me wonder if this was the same way in the eyes of the women who participated in Sati.

Rebecca Campos

The practice of Sati reminds me a lot of the Japanese practice of seppuku in Japanese culture. While Sati was seen as honorable and seppuku was not, both were viewed as the absolute last possible resort within the culture. The author’s informative piece was educating on the beliefs of another culture, even if this belief is no longer practiced. Another sad detail was the fact that women believed this was their fate if they were seen not “marriageable.” It’s unfortunate they were not seen as more valued and its a very good thing this practice is no longer allowed.

Antoinette Johnson

Indian traditions are different from western traditions and their practices that are valued to them seem cruel and unusual to us. I think Sati is a cruel tradition. If the women were able to decide that they wanted to die alongside their husband that would be fine because that’s their decision. But when the women’s husband dies and she chooses not to end her life, but she is drugged and killed against her wishes this becomes a cruelty that seems to target women. They still have children they love and want to raise especially if their husband dies a few months after their marriage. Now instead of their children having one dead parent, they have two.

Christopher Hohman

Nice article. India is indeed a land of many strange customs owing to its diverse background. Suttee is one of those strange customs. I remembering learning about it in my freshman history class and thinking wow. When the British arrived they put an end to Suttee as a legal act, perhaps one of the only good things they did while they ruled there. Still I bet that many Indians saw the law as intrusive and disrespectful. The British often came across this way to those they conquered especially to the Indians

Esperanza Rojas

This story and former tradition had me upset through the entire time I read it. Reading on how women would burn themselves because it was tration is just sad as a society and a country. But, I am a little confused as to why it was considered heroic and courageous, it didn’t really explain in detail but simply just stated the fact. Aslo, the fact that this wasn’t illegal until the late 1990’s is awstinishinh, I can understand if it was created in the 1500s lasted for 100 years or so, but to last into a modern century is extremely shocking and somewhat reassuring that some of the societies out there aren’t progressing as much.

Kaitlyn Killebrew

I believe this practice was also used on early civilizations from the Americas, i.e. Aztec and or Mayans. To read this as an informational article is intriguing, but reading this as a woman raised in the western society it’s quite chilling. Willingly throwing oneself in the fire after the death of their husband is beyond baffling, along with the usually many other wives. Or the thought that it was better to burn than to be “conquest” because that is a greater dishonor than death to me, is very similar to seppuku, a Japanese suicidal practice that samurais would do to avoid capture from the enemy. Also was considered a great honor. Dayabhaga in itself seems to be a divorce attorney’s nightmare. No matter what the inheritance was never given to the wife (widowed or not) and if she were to remarry, most likely not of her accord, then the inheritance would be given to the new husband and any children she may have with him, leaving her children from her first marriage with nothing.

Harashang Gajjar

In this age of inspirational feminism and focus on equality and human rights, it is difficult to assimilate the Hindu practice of sati, the burning to death of a widow on her husband’s funeral pyre, into our modern world. Indeed, the practice is outlawed and illegal in today’s India, yet it occurs up to the present day and is still regarded by some Hindus as the ultimate form of womanly devotion and sacrifice. Sati is the practice among some Hindu communities by which a recently widowed woman either volunteered or by use of force or commits suicide as a result of her husband’s death.The best known form of sati is when a woman burns to death on her husband’s funeral pyre.

Dev Chakraborty

This is a good attempt to write about Sati but unfortunately you have seen whole matter through foreign spectacles. You also mentioned a wrong information saying that “Jawahar” was practiced by Muslim women,hahaha,on the contrary Jawahar was practiced by brave Rajput Hindu women to protect their dignity from Islamic infidels. You need to understand core value of India and its culture before making any conclusion. Ask urself if Sati system prevailed and practiced with brutality then why Megasthenes,Fa-Hien,Huien-Tsang,Ibn-Battuta etc have not mentioned this in their writings about India. Be blessed.

Edgar Ramon

This might have been an acceptable practice when rape was a sure thing or perhaps for several other reasons, to accompany the husband who might have died in battle or something. I just could not agree with just committing suicide, I don’t agree that this should even be normal to westerners honestly. However I would better understand self-sacrifice, not suicide, as was the type by Jose Luis Sanchez del RIo, from the Cristadas in Mexico, who became a martyr. He did not commit suicide for the longing of a deceased family member, but for his God. Furthermore, martyrdom does not discriminate between sexes.