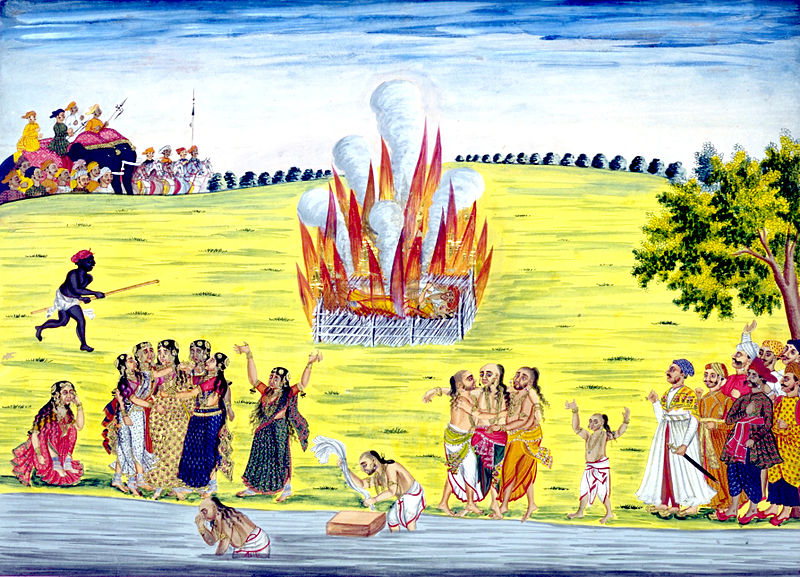

Sati, also known as “Suttee,” was a tradition that was practiced in ancient India from the early centuries BCE to the mid-1990’s. In this tradition, widows were burned at the side of their deceased husbands. There were many reasons behind this tragic form of suicide, but the act was seen as heroic and courageous. The tradition originates with the goddess Sati, who burned herself to death in a fire that she created through her yogic powers, which she obtained after her father had insulted her husband. Sati became an option for women in India who were not “marriageable,” according to social norms. Sati was first recognized in the Mahabharata, one of the two most well-known and important poems of India.1

“LAMP of my life, the lips of Death

Hath blown thee out with their sudden breath;

Naught shall revive thy vanished spark . . .

Love, must I dwell in the living dark?” -Suttee by Sarojini Naidu2

The practice of Sati is recounted by a first century BCE Greek author named Diodorus Siculus. Diodorus mentioned sati stones, which were memorials of all of the wives that have passed along with their husbands. A stone was created for each wife after she gave up her life, and these stones were all collected into a shrine. The earliest memorial that has been discovered dates from 510 BCE.3

Another practice that branched out from sati was the Jahuar, which was a sacrifice of any Muslim woman from the twelfth through the sixteenth century. It was believed that if a woman was burned, she would be safe from rape, which was worse than dying at the hands of a conquering enemy.4

Sati was also practiced by the Brahmans of Bengal, by the system of law from 1100 CE, which was called Dayabhaga. If a woman was widowed, her inheritance would be given to the children of her passed husband. If she were to remarry, her inheritance from her deceased husband would be given to the children and her new husband and her other children would not receive anything. If she passed along with her husband, the inheritance would be given to the children of her dead husband. This law was ended by the Mughal rulers Akbar and his father Humayun in the sixteenth century.5

In 1829, when India was informally ruled by Great Britain, the law to make sati illegal was passed because the act was seen by the British as harsh and cruel to women. Although it was made illegal, there were controversies over whether the sati practice was a religious act, and if so, should that be taken into consideration before prohibiting it.2

In 1987, Roop Kanwar, a woman from the village of Deorala in Rajasthan India, was married to her husband for only eight months before he died. She decided against taking her life in front of thousands of people. Politicians and activists believed that Roop Kanwar was then subsequently drugged by the liquid inside the seeds of an opium poppy flower, and pressured to take her life by those around her. Some people even say that she had super natural powers because her eyes were glowing bright red as she burst into flames. Police concluded that a group of men had been guilty of having drugged her, and they were placed under arrest.7

Sati was a rather harsh tradition, but the significance of these rituals was important to many Indian traditions. The thought of self sacrifice in this way is foreign to Western traditions, and the thought of being burned alive is worse. Sati is now illegal and no longer practiced, but the memories of the dead women from this tradition remain and they will always remind us of this social practice.8

- Kashgar, 2009, s.v. “Life in India: the practice of sati or widow burning,” by Linda Heaphy. ↵

- The Denson Journal of Religion, April 2015, s.v. “Interpreting Sati: the Complex Relationship Between Gender and Power in India,” by Cheyenne Cierpial. ↵

- Dorothy Stein, Burning Widows (University of British Columbia: Pacific Affairs, 1988), 466. ↵

- The Denson Journal of Religion, April 2015, s.v. “Interpreting Sati: the complex Relationship Between gender and Power in India,” by Cheyenne Cierpial. ↵

- Encyclopedia Britannica, March 2015, s.v. “Suttee,” by Wendy Dongiger. ↵

- The Denson Journal of Religion, April 2015, s.v. “Interpreting Sati: the Complex Relationship Between Gender and Power in India,” by Cheyenne Cierpial. ↵

- Encyclopedia Britannica March 2015, s.v. “Suttee,” by Wendy Dongiger. ↵

- Sophia Gilmartin, “The Sati, the Bride and the Widow: Sacrificial Woman in the nineteenth century,” Victorian Literature Vol. 25, No.1 (1997): 142. ↵

99 comments

Johnanthony Hernandez

Great article, having read parts of the Mahabharata, I had a basic understanding of Sati. But I didn’t know that it continued up until the end of the 20th century. I also didn’t know that the British had outlawed it because it was cruel to woman, while it does seem like something the British would do it did surprise me that they did that. While it was a tradition with religious beginnings to honor their dead husbands and the goddess Sati, it is understandable that most notorious case was among one of the last instances of Sati until it was done away with completely.

Gabriela Medrano

This Sati practice was a courageous yet frightening act done by these women. I could only imagine what these women must have gone through, first they lose their husband, and then they have to be sacrificed. What happened if the marriage had children? I am glad that this practice was banned because it can cause many harms to families and friends. The most shocking was that the most recent practice was about 30 years ago! Great article and awesome topic!

Briana Bustamante

Such an interesting topic to chose. I have never heard of anything about Sati. You explained the practice very well and I understand why women decided to sacrifice themselves after their husbands die. Thankfully the practice is no longer occurring because I feel that it is sad and unnecessary. I can see why your article was nominated for best in “Culture” and “gender history”. Over all, great work!

Nelson Smithwick

This was an incredibly interesting article, I had no idea that this ritual would continue all the way to the 1990s. I had heard before of rituals in which wives would be burned at their husbands funeral pyre, however I hadn’t known about this particular ritual of the Sati Indians. The case of Roop Kanwar was particularly tragic, being forced to take part in this ritual.

Andrew Gray

This is a very well written article on the cruel practice of Sati that sounds a bit romantic in words instead of action. Having said that I am glad that this practice was ended. This article captured my attention and is a well-researched article. Good job on this article I am looking forward to reading other articles you have published.

Marissa Gonzalez

This was a very interesting article relating to Indian culture. Living in today’s society in America, sacrificing your own life by being burned alive is definitely not the norm. However, these practices meant a lot to Indian culture. I know of other cultures that have painful and harsh traditions but this one is one of the most gruesome since women were actually being burned and killed. Your ending caught my attention because Roop Kanwar refused to take her life since her husband died. Also, because she was apparently drugged and pressured to do so which is not fair. Great article!

Tyler Sleeter

Wow, what an interesting topic. I had no idea that widows would do this kind of thing as a normal and culturally accepted behavior. It seems a little extreme as a way to control inheritance issues. I think that the example of Roop Kanwar is tragic, but I did not find it surprising that it took something that awful to make the practice of sati illegal. Human sacrifice, because that is what this is, should never be acceptable, even for religious purposes, and the British should have done more to make the act illegal when they first took control of India.

Aimee Trevino

Again, this is an extremely interesting article! This article gave a great explanation on a very cruel and unusual practice; Sati. It gives a look at a different culture, and even some of the sexism between men and women. Your article also shows just how undervalued women are in certain cultures, and that they meant little to nothing. Again, well done!

Mario Sosa

It must have taken a lot of courage and devotion for women to practice sati. I found the picture of the Suttee Shrine to be very eerie, which makes me wonder how many shrines are there? Incredible to think that sati was practiced for over two thousand years and has only stopped being practiced barely twenty years ago. Interesting topic, great job on the article!

Bailey Rider

This was a really interesting article to read. I had never heard of Sati before and it’s crazy to me that widows would kill themselves early along with their husbands. It just shows that different cultures have different customs and beliefs that other cultures might not understand, and it’s really interesting and cool to learn about these other customs. For women’s rights, I am glad that this custom no longer is performed.