The American Civil War was a defining period in the development of the United States we know today. This war was marked by heroic battles and immense amounts of human suffering, all in the name of the conservation of the Union and the abolition of slavery. Throughout the chaos of this war, many heroes rose and changed the outcome of the war through their efforts and ingenuity. One of these important figures is Jonathan Letterman, a determined Medical Officer serving in the Union army, answering the call for change and gaining the title of the “Father of Battlefield Medicine.”1

On July 21, 1861, at the first Battle of Bull Run, Dr. Letterman fought with the Army of the Potomac. This battle took place in Manassas, Virginia, approximately 220 miles from his birthplace Canonsburg, Pennsylvania. During this battle, Dr. Letterman first noticed the chaos and unorganized system of transporting fallen soldiers, and the inadequate care they subsequently received. This helped mold his plan for reform of the military medical system. While developing his plan, important battles were waged on.

Earlier in his career, Jonathan Letterman had graduated from Jefferson Medical College in 1849 and was soon granted the rank of assistant surgeon of the Army department, following in his father’s footsteps who was also a surgeon.2 After this, Dr. Letterman served in several campaigns against Native American tribes in California, New Mexico, Florida, and Minnesota.

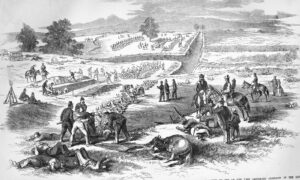

By March 1862, Dr. Letterman was at work developing his new battlefield medical techniques, such as an organized Ambulance corp, which had hopes of mobilizing care for his comrades and transferring the wounded off the battlefield in a quicker, more organized manner. A Civil War ambulance was a large wooden cart that was capable of accommodating four patients on stretchers and six patients seated in the front and back of the cart. It was first designed by Charles Tripler, who named the carriage the “Tripler Wagon.” Dr. Letterman saw this design as suitable for his first plan for his medical unit and it would soon be used after he worked out all the kinks in his system.3 He first started by analyzing and assessing the flaws of the inefficient system of transferring injured soldiers, identifying the inadequacy of the current system, and proposing a specialized unit tasked with efficiently transferring patients off of the battlefield to be treated. This unit needed to be organized and efficient, so Dr. Letterman made sure the unit would be uniquely marked so no confusion would happen when the Tripler wagons arrived. They would be noticed and used to the fullest of their abilities. For this wagon, comfort was needed for the already hurt soldiers, so it was standard for the ambulance to be covered to shelter the wounded from possible harsh weather. They had padded seating and systems to secure the patient when transporting to minimize further injury. Another problem soon to be fixed was the placement of the ambulance stations. Dr. Letterman found that it was best to have these stations in a quickly accessible spot, so that the ambulance could respond quickly to the wounded and secure them for transport to the next stage of medical care.

Also in March of 1862, Dr. Letterman was appointed as the Medical Director for the Army of the Potomac after previously having been a surgeon. He took on the task of reforming the record-keeping system to improve battlefield medicine. Dr. Letterman standardized record-keeping to allow for easier transfer of care of patients so that further care of the patients from field hospitals to larger facilities would be more seamless. The record-keeping developed by Letterman also introduced treatment planning, which would bring about a more accurate and detailed plan of action when caring for the wounded, thus ensuring that the care of the patient would be tracked better, and could be more adaptive based on the progress of the patient’s health. Along with this record-keeping reform came a better way to manage resources. By improving record-keeping, Dr. Letterman opened new doors for tracking and monitoring medical supplies being used in the field, making it easier for the army and medical forces to allocate supplies and aid. This made sure that field hospitals, facilities, and personnel had the proper equipment and resources to be successful in taking care of their patients.4 Dr. Letterman was a firm believer in having highly trained medical units. He believed that the best way to be ready for conflict is to be in conflict regularly. His philosophy was that training should be as realistic as it can be, as he famously said, “War is the only proper school for surgeons.”5 Another development under this reform was the new research and adaptation of the Medical system. By tracking patients and care, it became easier to analyze the overall effectiveness of procedures and treatments, opening doors for new implements of care for Physicians to use. Furthermore, record-keeping improved the overall coordination of the medical field by keeping records that patients could pass on their information to nurses and physicians. This ensured that surgeons could all plan accordingly for transfer to the correct facility and treatment of the patients, leading to the advanced evacuation of patients.6

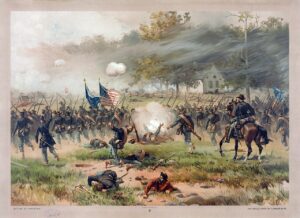

After these designs were completed over a seven- to eight-month period, the Battle of Antietam knocked at the door on September 17, 1862. The Battle of Antietam was extremely significant because it was considered the bloodiest battle of the Civil War. There were an estimated 22,000 casualties during this battle, the most American casualties in one day. This was because this war was fought between the American people on both sides of the conflict, adding to American casualties.7 Dr. Letterman’s new plans for reform were to be put to the test during this significant battle. During this battle, the new ambulance unit worked relentlessly for the entirety of September 17. The battle was bloody and ruthless over the northern territories that the Confederacy planned on collecting under General Robert E. Lee. However, the Union fought hard, under General George McClellan of the Potomac Army, to defend their state from the Confederate invasion. After a long, tiring battle, 23,000 soldiers were killed, wounded, or missing, leaving behind a dark and gloomy ambiance of the battle felt by both sides, Union and Confederacy alike. However, for the soldiers still alive, many had Dr. Jonothan Letterman to thank for his new implements in evacuating the fallen soldiers. Since there were many soldiers in combat within this battle, Dr. Letterman’s reforms were put to the real test and prevailed with many men treated, showing how valuable these new reforms were to decreasing mortality.

However, this daunting victory over the Confederacy won by the brave soldiers and medical units under Dr. Letterman and General McClellan gave President Lincoln the courage to make one of the most profound and moving speeches of any American President to ever live. This speech, though very short, had a heavy hand in its message, that all slaves held captive by the Confederate forces would be declared free. Although this sounds like an ethical and moral wall against slavery, there were military implications to this beautiful speech. It stood against slavery but also aimed to weaken the Confederate forces by disrupting their economy by giving hope and promise to those enslaved. By doing this, the Union hoped to have slaves standing up to their social structures and refusing forced labor from the Confederacy, overall weakening their war efforts. The War seemed to be coming to a climax and the balance of the United States would be pushed by the outcomes of the chaotic battles to come.8

On July 1, 1863, General Robert E. Lee had already pushed his war efforts further into Union territories to relieve pressure on the already destroyed war-torn Virginia. General Lee’s idea was to influence the Union public opinion on the war by demonstrating the Confederacy’s military prowess. However, Dr. Jonathan Letterman again worked long hours planning and tuning up flaws in his already solid system, preparing for another battle to further his search for a system that would aid in reducing battlefield fatalities. The Confederacy pushed into the town of Gettysburg where fighting escalated as they covered surrounding areas and engaged their opposition for northern territory. Many wounded were evacuated and more were treated for their injuries thanks to Dr. Letterman’s reforms. Many soldiers’ lives were saved.

However, this battle was not over after one day. On July 2, shots rang out near and far. From both sides of the battle, the fighting had yet again intensified. There were now three large points of interest during this battle: Little Round Top, a large hill located at the south end of Cemetery Ridge in Gettysburg, Devil’s Den, which was a boulder-riddled hill and rocky area located just south of the town of Gettysburg, and the Peach Orchard, which was indeed a beautiful peach orchard located southwest of Gettysburg.9 These conflict points were places held by Union troops that would heavily influence the fate of this battle. Providing cover in a thunderstorm of lead and explosions, the fighting carried through the day and the call for medical attention rang out just as loudly as the cannon fire. Dr. Letterman’s system was yet again put to the test of reliability in another blood-covered battle. The night once again was upon the tired soldiers, and the gunfire, along with the echoes of explosions, dwindled with the dying sunlight. During the night the medical personnel fought death off many of these soldiers, ripping them from death’s tight grip. These brave medics met problems such as the limiting visibility of the dark cloak of the night. The overwhelming injuries from the battle fought during the day seemed to keep coming far after the shots fainted. They also dealt with constant noise and chaos from the calls of their fallen comrades trying to treat those with the most severe injuries. The Medical personnel also faced limited rest time. Working on the wounded all day during the battle and continuing their work through the night just for some of those familiar faces to end right back under your care from the new day of battle was a long and daunting task with immense pressure and relentless work for these medics that fought hard to slap death’s hands away from their comrades. Again, the sun crept silently over the horizon for July 3, 1863, the third day of this blood-lusted battle. Shots rang out once again, and medics continued to fight for their comrades’ lives, rushing up and down the field in their units and snatching their tired bodies off the battlefield to be tended to.10 This would be the third and final day of this battle and it was just as deadly and ruthless as the first two days. The battle was fought hard by both sides with little to no advancements by the Southern forces as the battle continued to be fought. General Robert E. Lee grew more desperate and arranged for a charge directly for the Union forces, with General Lee ordering his troops to attempt to break through the center of the Union line on Cemetery Ridge in a charge known as “ Pickett’s Charge.” The charge was repulsed and the Confederate troops suffered significant casualties. The North once again held their ground and repelled the Confederate forces from their invasion attempt. Dr. Letterman’s system again showed its success on the battlefield, while there were firm accounts of how many were saved; it was reported by troops and higher command that the system did serve to be more efficient and organized, leading to a more secure handling of the wounded, leading to better treatment and an overall decrease in mortality. After this bloody battle, President Abraham Lincoln gave his famous speech, the “Gettysburg Address,” on November 19, 1863. During this powerful speech, President Lincoln addressed the point of human equality and preserving the Union so that the United States may prosper together, demanding that all slaves were to be freemen from that day.

Dr. Letterman worked countless hours for this very result, a decreased mortality rate, and more efficient moving of troops, and he finally achieved his success through these trying battles that supported the legitimacy of his work and process. After this battle, Dr. Letterman was appointed as the Surgeon General of the United States, and with this promotion, Jonathan Letterman continued with his contributions to a broader scale of the military. Once appointed as General Surgeon, he began to advocate for the implementation of his medical reforms within the entire U.S. His experience and knowledge during the Civil War highlighted and validated his proposal for a tested and proven system.11 Through this promotion, he continued to use his expertise to advance medical education and push for better-trained physicians in combat. Because of this, he advanced training programs to grow the physicians. Another advocacy that Surgeon General Letterman had was the improvement of health and sanitation. He began by advocating for more healthy and sanitary decisions while in the military. The importance of this was shown to him as the war progressed. Hygiene was essential for the prevention of disease and the health of soldiers.12 Letterman continued to make a difference to continue advancing medicine and creating a better medical system. After Letterman had been promoted and pushed some more reforms, he retired from the military and entered the next period of his life. During this period, he would continue to be involved in medical circles and keep connections with institutions to further share his knowledge. Dr. Letterman’s efforts were recognized as he had received Congressional Recognition on the input of his Medical system in the United States military. Congress passed a resolution recognizing his contributions to the improvement of military medical services.13

Dr. Letterman’s impact during the Civil war Military Medical system is an impact that has served and aided us many years after the retirement of Dr. Letterman. His vision and reforms not only evolved the treatment of wounded soldiers during the Civil War but also laid the groundwork for new medical care. The innovations created by Dr. Letterman had not only a nationwide impact but a worldwide impact on standard treatment and medical systems in the armed forces. The establishment of the triage system, the ambulance corps, and the specific details on quick, efficient medical care, drove his success and goal of an overall decrease in mortality rate.14 His efforts pushed far beyond the Civil War, by changing conflicts and shaping medical systems around the world. Because of his early revolutions and ideas, we now have further innovations to improve our health systems, further advancements in emergency surgeries, and evacuation of wounded. Through his story, we are able to see firsthand the lasting and important impacts brave and courageous individuals can have on those in need and those who come after. Dr. Jonothan’s developments and undying commitment altered how wounded were tended to on the front lines. His reforms laid a foundation for modern battlefield medical systems and greatly reduced the overall mortality rates among the injured.

- Brucey Rock, “Jonathan Letterman,” Fold3, January 14, 2014, https://www.fold3.com/memorial/640690553. ↵

- Brucey Rock, “Jonathan Letterman,” Fold3, January 14, 2014, https://www.fold3.com/memorial/640690553. ↵

- “Civil War Ambulance – Fort Scott National Historic Site (U.S. National Park Service),” accessed November 24, 2023, https://www.nps.gov/fosc/learn/historyculture/civil-war-ambulance.htm. ↵

- Ronald Wolf, “Techniques of Civil War Medical Innovator Jonathan Letterman Still Used Today,” www.army.mil, February 1, 2019, https://www.army.mil/article/216935/techniques_of_civil_war_medical_innovator_jonathan_letterman_still_used_today. ↵

- Jonathan Liebig et. al., “Major Jonathan Letterman: Unsung War Hero and Father of Modern Battlefield Medicine,” American College of Surgeons, 2016. ↵

- James M. Phalen, “The Life of Jonathan Letterman,” Records of the American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia 58, no. 2 (1947): 156–64. ↵

- James M. Phalen, “The Life of Jonathan Letterman,” Records of the American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia 58, no. 2 (1947): 156–64. ↵

- William T. Campbell, “Overworked, Undermanned and Indispensable: HOSPITAL STEWARDS IN THE CIVIL WAR,” Military Images 36, no. 4 (2018): 52–56. ↵

- Louis P. Masur and J. Ronald Spencer, “Civil War Mobilizations,” OAH Magazine of History 26, no. 2 (2012): 7–12. ↵

- Susan-Mary Grant, “(Dis)Embodied Identities: Civil War Soldiers, Surgeons, and the Medical Memories of Combat,” in Life and Limb, ed. David Seed, Stephen C. Kenny, and Chris Williams, Perspectives on the American Civil War (Liverpool University Press, 2015), 80–92, https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1ps3216.26. ↵

- Glenna R. Schroeder-Lein, The Encyclopedia of Civil War Medicine (London, UNITED KINGDOM: Taylor & Francis Group, 2008), http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/stmarytx-ebooks/detail.action?docID=1968811. ↵

- William T. Campbell, “Overworked, Undermanned and Indispensable: HOSPITAL STEWARDS IN THE CIVIL WAR,” Military Images 36, no. 4 (2018): 52–56. ↵

- John Lustrea and Jake Wynn, “Medical Revolution,” America’s Civil War 34, no. 4 (September 1, 2021): 12–14. ↵

- Susan-Mary Grant, “(Dis)Embodied Identities: Civil War Soldiers, Surgeons, and the Medical Memories of Combat,” in Life and Limb, ed. David Seed, Stephen C. Kenny, and Chris Williams, Perspectives on the American Civil War (Liverpool University Press, 2015), 80–92, https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1ps3216.26. ↵