Welcome to Kansas! Free State or Slave State? As a settler in the Kansas Territory, you may choose how to vote. It sounds straightforward, based on what was laid out in the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854; but it was far from easy. Settlers were not expecting the influx of Northerners promoting anti-slavery, nor were they expecting a large number of Southerners bringing their views of pro-slavery. Corruption, violence, and death were also not expected as a result of passing the Kansas-Nebraska Act. As a settler in the territory from 1854 to 1857, one would likely be an eye-witness to all of the destruction. Five settlers from the North were brothers; they moved to Kansas from Ohio hoping to start a new life. The brothers wrote to their father, John Brown, expressing concerns over the growing violence in the territory. They asked him to bring weapons so they could defend themselves against the Southerners who had flooded into Kansas, most from the neighboring state of Missouri, a slave state. Who was John Brown and what role would he play in Kansas becoming a free state or a slave state? After reading about John Brown, you will wonder whether he should be considered a hero or a martyr.

To better understand the climate that John Brown would face and the violence that would occur in Kansas, let’s look at a few laws that were passed and the motivation behind those laws. The Missouri Compromise, which was passed in 1820 shortly before James Monroe began his second term as President, set boundaries for future free and slave states, and allowed Missouri to be admitted to the Union as a slave state and Maine as a free state. The Compromise applied to the land that was acquired by the Louisiana Purchase. The boundary banned slavery from lands located north of the 36° 30′ parallel line. The process for admitting states into the Union under the Missouri Compromise had worked as intended for almost twenty-five years, but it did not address the issue of slavery in territories not yet acquired in 1820. Southerners argued that the Missouri Compromise restricted their rights to slavery in any territories including those outlined in the Missouri Compromise. The question over slavery was a heated issue in Congress for several years, especially after the newly acquired territory of California sought admittance to the Union as a free state. Neither the Northerners nor the Southerners wanted to compromise because the balance of power in Congress could easily shift, to the disempowerment of the minority. An attempt at a compromise was proposed by Henry Clay, Whig Senator from Kentucky and a key nationalist leader in the Senate. In 1850, his proposal combined several separate proposals into one. Congress was at an impasse on the great debate for more than six months. His proposal, however, was defeated. Stephen A. Douglas, a Democratic Senator from Illinois, proposed a series of measures regarding admitting new states and territories to the Union. Douglas’s proposals were based on the benefits of economic expansion for his state. His argument to his fellow senators was that they could vote for the measures that benefitted their state and defeat the others. This line of thinking aligned with the preference for sectionalism versus nationalism. In September of 1850, the individual components of the compromise were signed into law by President Fillmore. Two key outcomes of the legislation were that California was admitted to the Union as a free state. Also, the territories acquired from Mexico in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo would be allowed to determine their destiny as a free or slave state.1 This compromise calmed the ire of the Southern states just as they were threatening to secede. All seemed well for the nation again.

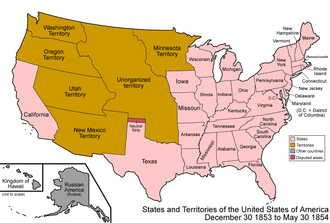

In 1854, Douglas wanted the future transcontinental railroad, which would be partially funded by the Federal government, to run through a mid-west terminus, namely through Chicago. Railroads could only be routed through developed territories. Douglas devised a plan for the railroads that required the unorganized territory west of Iowa to become fully organized for future statehood. Unfortunately, Douglas’ plan of territorial incorporation contradicted the Compromise of 1850 that he had championed just four years prior. Douglas sponsored the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 because of the economic benefit of the railroad to Illinois. He wanted the railroad to go through the Midwest; but the railroad could only be built on territories being organized for statehood. Author James L. Huston, in his review of the Kansas Nebraska Act of 1854 describes the legislation this way: “This act produced terrible consequences and perhaps deserves the title of the most ill-conceived and wretched piece of congressional handiwork in the nation’s history. More than any other single action this law put the United States on the path to Civil War.”2 Each territory would need to decide the question of slavery for itself. It was assumed that Nebraska would be admitted as a free state; but Southerners felt that they had an opportunity to influence Kansas, since it boarded Missouri, which was a slave state. President Franklin Pierce signed the bill into law on May 30, 1854. Author Huston summed the legislation this way: “By putting discussion of slavery in the hands of the settlers and taking it away from members of Congress, Douglas believed, as did many others, that the national agitation over slavery’s expansion would cease.”3 In a short time, Douglas and other members of Congress would see how wrong they were.

A vote was planned for the settlers of the Kansas territory to decide on whether Kansas should be a free state or a slave state. Before the voting, Northerners with their anti-slavery views and Southerners, mostly from Missouri, a slave state with their pro-slavery views, descended into Kansas. The election was held on March 30, 1855. One scholar described the actions for a pro-slavery vote in Kansas: “So-called Border Ruffians, led by Missouri senator David Atchison, streamed across the Missouri border into Kansas to stuff the ballot boxes with proslavery votes. Only 2,905 people were registered to vote in Kansas, but 6,307 ballots were cast. A mere 791 voted for antislavery.”4 The corrupt election caused turmoil within the territory, and many settlers who came to start their new lives in Kansas were caught in the political storm over slavery and felt threatened and wanted to protect themselves. John Brown, an abolitionist from the North, came to the Kansas territory and became the center of the growing disputes.

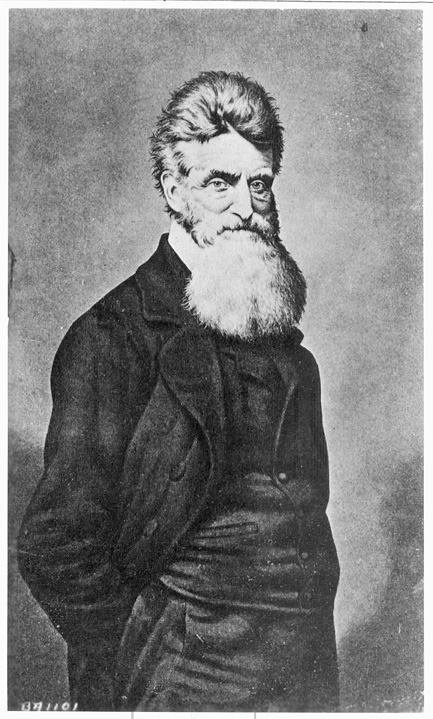

Who was John Brown and how did he become an abolitionist? Brown had humble beginnings and struggled financially his entire life. He was born in Torrington, Connecticut to Owen Brown and Ruth Mills on May 9, 1800. His family was devout Calvinists. Brown’s father worked as a tanner and raised his children with a heavy hand. At an early age, Brown was taught that slavery was wrong. He learned his lessons on slavery from his father, and Brown witnessed his father assisting runaways. Around twelve years old, Brown witnessed a young African-American boy being beaten, which shaped his work as an abolitionist.5 Initially, Brown studied for a Calvinist ministry, but decided to follow in his father’s footsteps as a tanner. John Brown was married twice and had a total of twenty children, nine of which died as children. He married his first wife, Dianteh Lusk at the age of twenty and had seven children with her. She died in 1832, shortly after giving birth to their son. In 1833, John Brown married Mary Ann Day. Together they had thirteen children, but only six survived into adulthood. Brown worked in several vocations and moved around from the 1820 into the 1830s with limited financial success. As an adult, Brown continued his work to free slaves. In his book, To Raise Up A Nation: John Brown, Frederick Douglas and the Making of a Free Country, author William King describes Brown and his role in establishing the League of Gileadites, a group formed to protect Black citizens from slave hunters: “The purpose of the league was to ensure an organized resistance to any attempt at the enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law.”6

Brown and his family were living in Ohio when five of his grown sons left drought-plagued Ohio in 1854 to take up homesteads in the newly opened Kansas Territory. At this time, Brown was 54 years old and described as a gentleman who never fired a gun in anger or seen a man murdered. When Brown’s sons asked their father to bring arms to Kansas, John Brown would begin his mission to fight to free slaves; but at what personal sacrifice? King describes Brown’s efforts to raise money to bring arms to Kansas. Brown spoke at a convention on anti-slavery. There he asked for funds: “he must appeal for aid; as for himself, he could not go unless he could go armed. Funds were contributed on the spot, amounting to sixty dollars in all.”7 The public support for Brown’s mission was a revelation to him. It spurred him to gather more support before arriving in Kansas. King further describes Brown’s actions in Akron, Ohio: “He spoke publicly, successfully obtaining donations of ammunition, clothing, a box of muskets, and ten double-edged swords.”8 Brown and his companions arrived in Kansas on October 7, 1855, eighteen months after his sons first wrote to him. John Brown’s life was about to change. Violence began to erupt between pro-slavery and anti-slavery groups across Kansas. Lawrence, Kansas experienced more of the small scale, and then large scale violence since it was the political center of the free-state champions’ stronghold, a critical stop on the Underground Railroad, and a base for Abolitionist organizations.9 The turning point of the violence began on May 21, 1856, when a mob of more than 800 Southerners descended on the town of Lawrence with a blood-red flag, on which was inscribed “Southerner Rights.” The free-soilers had no protection; the residents fled their homes as the Southerners ransacked their town. Kansas became center-stage as the debate on slavery heated up. News of the violence spread to the Northern states, and they began sending clothing, food, and other supplies to the free-soil settlers.10

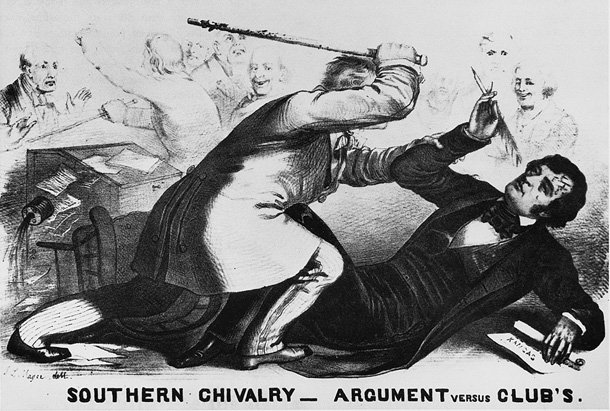

The Kansas feuds played out on a national level. On May 22, 1856, in Washington, D.C. Senator Charles Sumner, an abolitionist from Massachusetts, was attacked and beaten with a cane by Congressman Preston Brooks of South Carolina, after giving a speech in the Senate titled, “The Crime Against Kansas.” Senator Sumner accused Southerners of “raping and plundering the virgin territory.”11 Brooks was outraged by Sumner’s accusations and beat Sumner into unconsciousness with the gold head of his heavy cane. Brook’s beating lasted until his cane broke. Interestingly, Southerner publications celebrated Brooks for the assault, where he was described as a hero. John Brown wanted revenge for Lawrence, Kansas. When Brown heard of the Brooks beating of Sumner, he was further enraged. One of Brown’s followers urged for the group to be cautious, but Brown replied, “Caution, caution… it is nothing but the word of cowardice.”12

In response to the May 21 attack, John Brown, along with four of his sons and three other settlers, marched through Pottawatomie Valley in Kansas territory on May 24, 1856, with the purpose of taking vengeance on the Southerners for their attack on Lawrence, Kansas. It was uncharacteristic of Brown to submit to violence, but he and his followers dragged five Southern men from their cabins and beat the men to death with swords. When Brown failed to locate other intended victims, his men confiscated horses and disappeared into the night. The incident was remembered as the Pottawatomie Massacre. “This cruel act raised the stakes for the Southerners. Brown and his followers hid in the wilderness after the massacre arising occasionally to battle proslavery forces.”13 The press—particularly, the abolitionist journalists—sensationalized Brown’s work in Kansas. Brown became known as “Old Brown of Osawatomie.” Brown justified his actions by claiming that he was on a mission from God to free black men. The press referred to the violence as “Bleeding Kansas.” Kansas became a symbol of the sectional controversy gripping the nation. In his book, John Brown’s War Against Slavery, historian Robert McGlone describes the atmosphere this way: “Open warfare now broke out between proslavery posses, composed largely of Missourians, and free-state militia companies and irregulars.”14 The two attacks in May were the prelude to more Kansas struggles. Brown and his men would occasionally come out of hiding and defeat small forces of Southerners, as they did on June 2 at Black Jack, Kansas. The Southerners kept up their fighting too. On August 30,1856, a proslavery group burned the town of Osawatomie in revenge for the violence that took place in Pottawatomie in May. McGlone describes the price Brown’s family paid: “…in retaliation for the [May] killings, easily dispersing Brown’s men in a firefight and killing Brown’s unarmed son, Frederick.”15 After these incidents, the violence continued throughout Kansas with more than fifty deaths from multiple confrontations between Southerners and Northerners. Although Brown was not responsible for all these confrontations, he received the most press and is most associated with anti-slavery campaigns. These acts made Brown “nationally famous as an irreconcilable foe of slavery.”16

What happened to John Brown? After the fights in Kansas, John Brown continued his crusade fighting for freedom for all slaves. With financial backing from Eastern abolitionists, Brown went to Harpers Ferry, Virginia (now West Virginia) about eighteen months after the Kansas fighting. Brown wanted to start a slave insurrection in the South. Although Brown thought he had carefully laid out a plan to capture the arsenal, he did not anticipate the local militia response nor the response from the U.S. government. “On October 16, 1857, Brown and twenty-one of his followers (two of which were his sons) captured the arsenal at Harpers Ferry. A battle ensued with a company of marines led by Col. Robert E. Lee. Brown was wounded in the attack and ten of his men were killed.”17 Brown surrendered to Lee. Brown’s attack created more fear among the Southerners and shock among the Northerners. For his attack at Harper’s Ferry, Brown was tried for murder, was found guilty, and was hung on December 2, 1859. McGlone describes John Brown as “he was not the first ‘insurrectionist’ or adventurer to claim national attention. But he was the first to use national press to plead a cause and martyrdom.”18 I am surprised that Brown is regarded as a hero and a martyr. Today, I think Brown would be regarded as a zealot.

Violence in Kansas began to temporarily taper off. The Free State party regained control and wrote a constitution abolishing slavery. One scholar summed up the episode this way: “The bloody conflict in Kansas demonstrated the tenuous nature of the comprises regarding slavery that had occurred to date and fueled the tensions that led to the secession of seven Southern states between the election of Abraham Lincoln in November 1860 and his inauguration in March 1861.”19 Kansas was admitted as the 34th state to the Union on January 29, 1861, as a free state. During the Civil War, hundreds of slaves fled Missouri to settle in Kansas. Violence would erupt there again in 1861 as the Civil War became the manifestation of Brown’s initiative to end slavery.

- James L. Huston, “Kansas Nebraska Act of 1854, “Major Acts of Congress” 2 (2004): 227. ↵

- James L. Huston, “Kansas Nebraska Act of 1854, “Major Acts of Congress” 2 (2004): 226. ↵

- James L. Huston, “Kansas Nebraska Act of 1854, “Major Acts of Congress” 2 (2004): 229. ↵

- Jennifer Stock, ed., The Bleeding Kansas Crisis 1854 in North America (Farmington Hill, MI: Gale, 2014), 1. ↵

- Robert E. McGlone, John Brown’s War Against Slavery (Cambridge, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 49. ↵

- William S. King, To Raise Up A Nation: John Brown, Frederick Douglas and the Makin of a Free Country (Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing, 2013), 22. ↵

- William S. King, To Raise Up A Nation: John Brown, Frederick Douglas and the Making of a Free Country (Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing, 2013), 36. ↵

- William S. King, To Raise Up A Nation: John Brown, Frederick Douglas and the Making of a Free Country (Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing, 2013), 36. ↵

- Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, 2021, s.v. “Lawrence.” ↵

- Public Broadcasting System, “The Abolitionist,” PBS (website), accessed September 28, 2021, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/the-abolitionists-pottawatomie-massacre. ↵

- Public Broadcasting System, “The Abolitionist,” PBS (website), accessed September 28, 2021,https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/ americanexperience/features/the-abolitionists-pottawatomie-massacre. ↵

- Public Broadcasting System, “The Abolitionist,” PBS (website), accessed September 28, 2021, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/the-abolitionists-pottawatomie-massacre. ↵

- Biography, s.v. “Brown, John. ↵

- Robert E. McGlone, John Brown’s War Against Slavery (Cambridge, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 11. ↵

- Robert E. McGlone, John Brown’s War Against Slavery (Cambridge, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 11. ↵

- Funk and Wagnalls New World Encyclopedia, 2018, s.v. “John Brown.” ↵

- Funk and Wagnalls New World Encyclopedia, 2018, s.v. “John Brown.” ↵

- Robert E. McGlone, John Brown’s War Against Slavery (Cambridge, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 203. ↵

- Jennifer Stock, ed., The Bleeding Kansas Crisis 1854 in North America (Farmington Hill, MI: Gale, 2014). ↵

20 comments

Dort

Do any of you commenters actually read the historical documents?

Only thing I can comment is that you have the dates wrong. He didn’t do Harper’s ferry in 1857. He did it in 1859. And died just a bit later.

Anna Steck

I liked the article a lot. In the background, I was surprised that senators thought the Kansas Nebraska act would curb some of the political tensions of the time. I was also shocked how prevalent political travel was for the vote on slavery’s legality. When I was introduced to John Brown in high school, we examined why our textbook called him crazy and attributed his rebellion to his mental incapacity. This article did not ride off this rebellion at all, but it did question the implications of such a violent revolt. I find this a fascinating question given the actions of John Brown in the face of the obvious evil he was fighting.

Mateo Ortega-Rios

Hey Samuel, I really enjoyed reading your article, the story of John Brown was first introduced to me in my Junior year of high school. I really liked when you brought up his childhood in the middle of the article, it was able to give me at least in my head a throwback and give me a better picture of John Brown. The image used in the header of the article is one that really allows one to see how impactful that picture is and how violent the times were during that era.

Courtney Mcclellan

Really good article! I find it funny that John Brown was described as mostly docile when you look at his anger with the pro-slavery activists.I wonder why he wasn’t arrested after he had killed since he was able to move on and continue his fight to end slavery in other states.I didn’t know that Brown was very Christian and it seems backwards since most Christians were not condemning slavery and instead were promoting it.

Kenneth Cruz

Very strong opening to your article, Sam. I was pulled in immediately and felt compelled to keep reading. I like how you gave us some insight as to who John Brown was. I can tell you put a lot of effort into writing this piece. Thank you for your effort because in the end, I gained a better understanding of this historical figure.

Vanessa Preciado

I really enjoyed reading this article. I remember first hearing about this guy John Brown in history class, at first it was a quick skim of him, but already his story was interesting. Reading this informative article shed light on his life and what molded him to become this way as a child to a grown up, and a big important thing it shed light on was his anti slavery personality. I do think it’s wrong how he died, but so many people died back then because lack of common sense and human rights. Overall this article kept me moving forward, great job!

Laura Poole

Great article! I found myself locked in as I was reading it. I loved knowing more about John Brown and his personal life. He was a hero of Kansas in my opinion and was ahead of his time. I wonder how he felt about the Civil War that soon erupted after Bleeding Kansas. I can tell you did deep research to dig up his story and worked hard to put it together cohesively. Great work!

Esteban Serrano

Hey Samuel,

Great article! Very thorough research and interesting topic. I think Brown, being anti-slavery, was very dynamic in his approach to the problem. To even more powerfully, in terms of the common social philosophy of people during the time, he used the Christian belief, saying God was sending him on a mission. This is really fascinating because of the movement he was trying to accomplish, and dangerously and boldly did so during the time. Great work on the research once again, and congratulations on publishing the article!

Daniel Diaz

It’s a strange correlation that they’re making between John Brown and anti-slavery. I believe Brown was anti-south but not necessarily anti-slavery. Though he uses God to valid his claims against injustice, I feel he is more about pushing what he believes his people should follow versus what the law of the land says.

Elliot Avigael

I love the story of John Brown. I found it interesting that Robert E. Lee was the one that would suppress the rebellion and later become the primary general of the CSA. I admire John Brown for his determination to end slavery, but I don’t think that excuses the murder of innocents just based on the fact that they are Southerners that are pro-slavery. For a rebel or insurrectionist to be “noble” (for lack of a better word), in my opinion, they must strictly adhere to only attacking government property and resources, not innocent people that are just trying to live their lives.

Brown, and even General Lee for that matter, were certainly a flawed men, but I wouldn’t call them evil. Tensions were high at this time, and I’m not sure what any of us would do if we were to be sent back in time to Bleeding Kansas.