Madagascar, March, 1698 – With half a crew dead of disease, another half gone due to mutiny, one ship badly in need of repair, another ship filled with riches, and just thirteen men left to help him, Captain William Kidd was in dire straits. With his expedition crumbling around him, Kidd made the decision to abandon his first ship, the Adventure Galley, in favor of his more recent capture, the Quedah Merchant (a 500-ton Armenian trading ship) and sail towards the British-controlled island of Anguilla in the Caribbean.1 Here Kidd would learn that he was wanted by the British crown for piracy, and that during the time it took him to get from Madagascar to Anguilla, all colonial governors of the British empire were ordered to secure the capture of Kidd and the remainder of his men.2 So how did Captain Kidd become entangled in such a treacherous affair, and how did he fall so far from the good graces of the British crown?

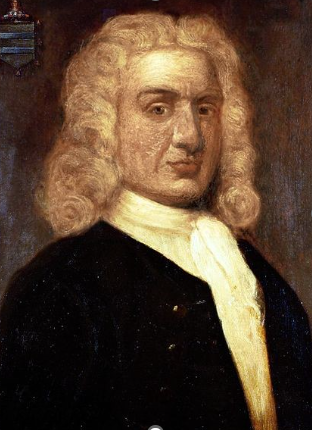

To understand Kidd’s fall, we must first understand his rise, specifically within the British Navy during the latter half of the seventeenth century. There are two main instances where Kidd’s actions helped elevate his notoriety among both the British public and the ruling elite, the first being his success at defending the waters around New York from a hostile privateer following the events of the Glorious Revolution (1688) and the upheaval it brought to the British empire. For his actions, Kidd was awarded £150 by the Council of New York several years later, in 1691. Kidd’s second act of distinction came during King William’s War (1689 – 97) when he fought a naval engagement against the French under the command of Colonel Hewetson. Hewetson would later write a report speaking highly of Kidd’s actions during the battle, further elevating his status as a capable seaman.3

Yet, the event that garnered Kidd the greatest amount of political and social clout among the New York elite wasn’t his military endeavors, but his marriage to the wealthy New York socialite Sarah Oort on May 16, 1691. The union helped to solidify Kidd’s reputation as both a gentleman and a prominent member within New York and the surrounding areas. He would also come to own his own sloop during that time and would eventually sail to London for trade purposes in 1695. It was there in London that Kidd would meet Richard Coote, the 1st Earl of Bellomont and colonial administrator who oversaw New York, Massachusetts Bay, and New Hampshire from 1695 until his death in 1701. Kidd’s status as a gentleman and maritime hero, and a recommendation from Robert Livingston (a prominent landholder and important political official from New York), would prompt Coote to offer him a position in a newly formed syndicate, headed by none other than King William III himself. The syndicate’s purpose was to split the reward of captured enemy/pirate vessels among the members, with King William III receiving 10% of the profits. Each of the members (of which there were eleven including Kidd) were all high-ranking government officials and landholders who contributed to the purchase of the merchant ship Adventure Galley, which was outfitted with armaments needed for ship hunting.4

Kidd would ultimately accept Coote’s offer and would be given two commissions: The first, given on December 11, 1695, gave Kidd explicit permission to hunt and capture enemy ships belonging to the French king and those subordinate to him, as well as other miscellaneous vessels not directly belonging to France, and to log every single capture so they could be confiscated properly in British port territory. The second commission, given January 26, 1696, gave Kidd permission to seize any and all pirate vessels, English or not, and to confiscate any items onboard. With those commissions, Kidd disembarked on April 23, 1696, his Adventure Galley weighing a total of 287 tons, with thirty guns and a crew between seventy and eighty men. It is at this time that Kidd would experience the first snag in his ill-fated voyage.5 Upon his departure from England, several officers of the king had decided to impress (forced military service) a selection of Kidd’s men, and although Kidd was able to save most of them from that impressment, he still lacked a full force to continue with his mission.

To try and remedy this, Kidd had decided to stop in New York before setting sail for the waters of Madagascar. This frustrated Coote, as he had wanted Kidd to take a direct route to Madagascar, rather than detouring to New York first.6 When reaching New York Harbor, Kidd would hit another snag, this time in terms of the commission agreement. When Kidd had made the call for recruits, he had promised his men a share of the spoils captured, but under the agreement made by Coote, Kidd and his crew were not to be paid until they had properly turned in their captured vessels. Kidd would also be responsible for paying Coote back the money he had spent to finance the voyage. These two stipulations meant that the only way Kidd could pay his crew and Coote was to capture enough ships to do so. It would be this financial onus that would come back to bite Kidd later on.7

Kidd’s crew quickly swelled to about 154 men, and by September of 1696, Kidd departed New York for Madagascar.8 Now, the primary purpose for Kidd being sent towards Madagascar itself has to do with another chronic rivalry that was being fought between the East India Company and the groups of pirates occupying the waters in and around the Red Sea. In fact, the creation of the syndicate itself was due mainly to the EIC petitioning King William III to send support to help alleviate the rampant piracy that the company was dealing with at the time.9 Kidd eventually reached Madagascar in late 1696 and continued to sail until he reached the island of Johanna (or Anjouan) in the southwestern part of the Indian Ocean in late March of 1697. At Johanna, it was reported that around fifty crewmen had died, presumably from disease, within a single week. From here, he continued sailing even further until he had reached the coast of Malabar (the southwestern coastal region of India) six months after he had left Johanna.10

Kidd then spent a large portion of his time in and around the Indian Ocean region, where he went on to capture two French vessels on two separate occasions, the first in November of 1697, and the second in February of 1698. However, these captures coincided with the signing of the Peace of Ryswick, ending the hostilities between England and France. Kidd was fortunate enough that an article in the treaty stated that any vessel seized beyond the equator within six months of the treaty being signed was not illegal.11 He also went on to capture his most valuable vessel yet, the Quedah Merchant, in January of 1698. Yet, this good fortune proved to be Kidd’s undoing. As it happened, the captain of the ship was not only an Englishman but had produced a French pass that offered him protection from the French crown. While it was still legal for Kidd to confiscate French property after the peace agreement, he had confiscated property from an Englishman instead, which was out of bounds for Kidd’s commission.12 With this capture and the other two French vessels in his possession, he began to make his way back towards Madagascar. Yet, Kidd’s good fortune was not to last long.

Upon arriving in Madagascar, Kidd came into contact with an actual pirate by the name of Robert Culliford. Not much is known about what exactly took place during their meeting except for several key moments. The first part of their encounter saw Kidd and Culliford engage civilly with each other.13 The second part saw about 3/4 of Kidd’s men mutiny and join with Culliford, most likely due to the negligible condition of the Adventure Galley at that point (which desperately needed repairs after almost two years at sea) and the underwhelming success of their privateering exploits, even with the capture of the Quedah Merchant. With few options left, Kidd decided to scuttle the Adventure Galley (salvaging what he could before he did so) and prepared to sail with the Quedah Merchant instead.14 Not much is known about Kidd’s activity between the period of the mutiny (around March 1698) and Kidd’s decision to travel back to New York in November of that same year. What is agreed upon is that after the voyage reached the Caribbean in April of 1699, Kidd had assessed that the Merchant would need to reach a port soon for a much-needed resupply and hull cleaning. Upon reaching the island of Antigua (in the Lesser Antilles region of the Caribbean), Kidd was devastated upon hearing, for the first time, his wanted status as a pirate.15

As timing would have it, while Kidd was beginning his voyage back to New York in November, the EIC had reported his capture of the Quedah Merchant to the Lords Justice on November 18, 1698. Five days after that report, all colonial governors of British territory were ordered to bring Kidd in for piracy.16 This meant that Kidd had been a wanted man for almost five months, and his plans to sail home to New York had changed drastically. Kidd, who was familiar with the waters of the Caribbean from his time in the military, sailed immediately for the port of St. Thomas, which he knew would be a friendly place for him and his men to weigh anchor. When he reached St. Thomas, Kidd’s numbers dwindled even further. Five of his remaining thirteen would depart for the island and Kidd’s brother-in-law Samuel Bradley, who was sick by the time they reached St. Thomas, would be left in the care of the locals.17 Taking what men he could, Kidd decided to continue his return to New York and to attempt to contact James Emmot, a lawyer who had attended the same church Kidd had in previous years.18 By the early summer, Kidd had sailed with the Quedah Merchant as far as the Mona Passage (the strait that divides Cuba and Puerto Rico) before he was forced to abandon the ship in favor of a smaller sloop called the Antonio.

That June, Emmot and Kidd met just outside Rhode Island. After their meeting, Emmot took a boat back to Boston, where he met Duncan Campbell, the city’s postmaster, and convinced him to sign a petition in favor of Kidd, which Emmot followed up by asking for Kidd’s pardon. Emmot’s actions caught the eye of Coote. Coote, who at this point had disavowed Kidd in the eyes of the public, didn’t trust Emmot and his intentions of representing Kidd. Seeing an opportunity to secure Kidd into custody, Coote decided to contact Kidd through Campbell, and promised him a pardon if Kidd were innocent of the charges as Emmot had claimed.19 This would be Kidd’s final mistake, with Coote managing to apprehend Kidd and secure him in a Boston jail on July 6, 1699.20

Kidd remained in Boston for seven months before being sent to England to stand trial.21 Just before his arrival in London, the House of Commons, who knew the powerful backers of Kidd’s initial commission, feared that any one of them might come to Kidd’s aid in the trial and so resolved to not move forth with it until Parliament reconvened. It would not be until March of 1701 that Kidd was brought before the House of Commons, at which point the members heard his testimony.22 Based on Kidd’s narrative, the House would allow Kidd to be tried in “the ordinary way,” and after a short, yet rigorous trial, Kidd was ultimately sentenced on one count of murder, and five counts of piracy. The murder sentencing was a part of an earlier controversy just before Kidd had been labeled a pirate by the British crown. It consisted of Kidd and one William Moore, a gunner on board the Adventure Galley, who according to witness testimony had been struck on the head with a bucket by Kidd after refusing to fire at a Dutch merchant ship passing by them. The blow by Kidd ultimately killed Moore, to which Kidd argued his innocence at his trial, saying that he had not meant to kill the gunner. Kidd’s pleas, ultimately, were rejected by both the court and jury.23

And so, on May 23, 1701, Captain William Kidd was hung at Execution Dock, London. His reputation as a Privateer-turned-pirate inspired countless retellings of his exploits across the Caribbean, Madagascar, and India. Kidd’s likeness has been molded and remolded through the many ballads and shanties that bear his name, and following his death there were many rumors (now turned legends) concerning almost every aspect of his life.24 From the battles he fought, the places he’d been, and (perhaps the most popular legend of them all) the treasure he’d obtained, Captain Kidd has lived on in the maritime world as a man shrouded in both infamy and mystery. Yet, perhaps we may better see him now as the once highly respected Captain Kidd, now destined to have his name echoed in infamy.

- Dunbar Maury Hinrichs, “Captain Kidd and the St. Thomas Incident,” New York History 37, no. 3 (1956): 266. ↵

- Frank Monaghan, “An Examination of the Reputation of Captain Kidd,” New York History 14, no. 3 (1933): 251. ↵

- Morton Pennypacker et al., “CAPTAIN KIDD: Hung, Not For Piracy But For Causing The Death of a Rebellious Seaman Hit With a Toy Bucket,” New York History 25, no. 4 (1944): 484-485. ↵

- Morton Pennypacker et al., “CAPTAIN KIDD: Hung, Not For Piracy But For Causing The Death of a Rebellious Seaman Hit With a Toy Bucket,” New York History 25, no. 4 (1944): 486. ↵

- Morton Pennypacker et al., “CAPTAIN KIDD: Hung, Not For Piracy But For Causing The Death of a Rebellious Seaman Hit With a Toy Bucket,” New York History 25, no. 4 (1944): 487. ↵

- Morton Pennypacker et al., “CAPTAIN KIDD: Hung, Not For Piracy But For Causing The Death of a Rebellious Seaman Hit With a Toy Bucket,” New York History 25, no. 4 (1944): 487. ↵

- Morton Pennypacker et al., “CAPTAIN KIDD: Hung, Not For Piracy But For Causing The Death of a Rebellious Seaman Hit With a Toy Bucket,” New York History 25, no. 4 (1944): 488. ↵

- Morton Pennypacker et al., “CAPTAIN KIDD: Hung, Not For Piracy But For Causing The Death of a Rebellious Seaman Hit With a Toy Bucket,” New York History 25, no. 4 (1944): 491. ↵

- Willard Hallam Bonner, “‘Clamors and False Stories’ the Reputation of Captain Kidd,” The New England Quarterly 17, no. 2 (1944): 180, https://doi.org/10.2307/361873. ↵

- Morton Pennypacker et al., “CAPTAIN KIDD: Hung, Not For Piracy But For Causing The Death of a Rebellious Seaman Hit With a Toy Bucket,” New York History 25, no. 4 (1944): 491. ↵

- Morton Pennypacker et al., “CAPTAIN KIDD: Hung, Not For Piracy But For Causing The Death of a Rebellious Seaman Hit With a Toy Bucket,” New York History25, no. 4 (1944): 493. ↵

- Frank Monaghan, “An Examination of the Reputation of Captain Kidd,” New York History 14, no. 3 (1933): 251. ↵

- Frank Monaghan, “An Examination of the Reputation of Captain Kidd,” New York History 14, no. 3 (1933): 251. ↵

- Dunbar Maury Hinrichs, “Captain Kidd and the St. Thomas Incident,” New York History 37, no. 3 (1956): 266. ↵

- Dunbar Maury Hinrichs, “Captain Kidd and the St. Thomas Incident,” New York History 37, no. 3 (1956): 267. ↵

- Frank Monaghan, “An Examination of the Reputation of Captain Kidd,” New York History 14, no. 3 (1933): 251. ↵

- Dunbar Maury Hinrichs, “Captain Kidd and the St. Thomas Incident,” New York History 37, no. 3 (1956): 267. ↵

- Morton Pennypacker et al., “CAPTAIN KIDD: Hung, Not For Piracy But For Causing The Death of a Rebellious Seaman Hit With a Toy Bucket,” New York History 25, no. 4 (1944): 494. ↵

- Morton Pennypacker et al., “CAPTAIN KIDD: Hung, Not For Piracy But For Causing The Death of a Rebellious Seaman Hit With a Toy Bucket,” New York History25, no. 4 (1944): 494. ↵

- Willard Hallam Bonner, “‘Clamors and False Stories’ the Reputation of Captain Kidd,” The New England Quarterly 17, no. 2 (1944): 183, https://doi.org/10.2307/361873. ↵

- Willard Hallam Bonner, “‘Clamors and False Stories’ the Reputation of Captain Kidd,” The New England Quarterly 17, no. 2 (1944): 183, https://doi.org/10.2307/361873. ↵

- Frank Monaghan, “An Examination of the Reputation of Captain Kidd,” New York History 14, no. 3 (1933): 251. ↵

- Morton Pennypacker et al., “CAPTAIN KIDD: Hung, Not For Piracy But For Causing The Death of a Rebellious Seaman Hit With a Toy Bucket,” New York History 25, no. 4 (1944): 509. ↵

- Willard Hallam Bonner, “The Ballad of Captain Kidd,” American Literature 15, no. 4 (1944): 362, https://doi.org/10.2307/2920762. ↵

5 comments

Gaitan Martinez

I have always heard of Captain William Kidd, but never actually learned the story. When I do think of an outlaw named Kidd, I think of Billy the Kid, but I wonder if the pirate influenced the cowboy? Anyways, very intriguing read, and I didn’t think a pirate would be so involved in politics, but maybe it wasn’t his choice? However, he did marry Sarah Oort.

Nicholas Pigott

Hi Nathaniel! First off, your storytelling ability is just incredible, and I’m so glad to have read this incredible article on such an interesting historical figure, almost like a character from a movie or show. I love the story you’ve made here and the photos along it. Great job on the sources for this article as well, and great work overall!

Sebastian Hernandez-Soihit

Very effective storytelling here! Not very discussed today but definitely very important. Very rich in information and very appropriate imagery offered to the readers. Great work!

Quinten Mero

The storytelling here is amazing! The way you have portrayed Captain Kidd’s story in your article certainly does not disappoint. From Captain Kidd’s commission as a British privateer to his unfortunate downfall detailed in your exposition, this man’s story, though riddled with strife and misfortune, is most definitely one for the history books and I believe that you have told it outstandingly well.

Jonathan Flores

this article is very well written, and I appreciate a deep dive into a facet of history that is not widely known. As a history buff, I appreciated your style of writing that followed a cohesive and chronological series of event. In other words, your writing flowed well, and I can say that I successfully learned many things from your writing. I previously was unaware of Kidd and now I feel as though I have a lot of information on him.