How tragic is it when an innocent person goes to prison or is wrongfully convicted and sentenced to death? Our judicial system is suppose to be fair. However, there have been numerous cases in which a defendant has been pronounced guilty, but is later found to be innocent. The case of Thomas Cornell is an example of this. He was sentenced to death for murdering his own mother, Rebecca Cornell. There is no evidence for the death of Rebecca, yet I argue that a jury wrongfully convicted Thomas. What happened to Rebecca Cornell that night remains a mystery. However, it is possible that Rebecca committed suicide, and it is also possible that a group of people from the outside broke in and brutally murdered her. These plausible scenarios are, in fact, more probable than is the case for Thomas, her own son, murdering her.

Seventy-three year old Rebecca Cornell’s last moments on this Earth have had to have been one of the strangest, most peculiar moments ever. In early February 1673, Rebecca was found burnt, with flames all around her, lying some distance away from the hearth in the downstairs room of her house when Sarah, Thomas’ wife, had asked their son to ask Rebecca if she wanted something to eat. However, when he went downstairs, he noticed Rebecca’s body so badly burnt that he almost could not recognized her.1 Hours before this occurred, Thomas had spent more than an hour talking with his mother when he decided to go upstairs with his wife and kids. He had left his mother peacefully sitting by a large fireplace in her bedroom smoking a clay pipe.

According to the jury, Thomas Cornell may have murdered his mother, but there are other plausible explanations for what could have happened that night. For one, Rebecca could have committed suicide. James Moills, a good friend of Rebecca, testified that on the day of Rebecca’s death, he had noticed that Rebecca had looked ill, and did not seem herself on the day of her death. He then said that he continued to check up on her throughout the day to make sure that she was okay. Rebecca was ill the entire day on the day of her death. This meant that Rebecca could have fallen by the fireplace by herself. Ill people tend to feel clumsy due to how bad their body is at that state, resulting in less self control.2

Another possible reason for what could have happened on the night of Rebecca’s death is that she could have been murdered by a person or a group of people because two days after Rebecca’s death, John Briggs, Rebecca’s brother in law, claimed he was visited by Rebecca’s ghost, who stated, “Twice sayd, see how I was burnt with fire?” Rebecca was trying to tell her brother-in-law that her death was no accident. She failed to accuse the specific person of her death, but told Briggs that it was someone. Briggs took his testimony to the court and told the officials what he had seen. In the seventeenth century, protestants believed that the spirit of a dead person would appear if there had been “an injustice that might not be detected by other means.” They believed that such a spirit’s appearance was God’s way of ensuring that a murderer would be exposed.3 This then helps me conclude that Rebecca could have been murdered by a person or group of people, because two doors are connected to Rebecca’s bedroom. One is connected to the inside of the house while the other is connected to the outside. People from the outside had access to Rebecca’s bedroom, and if executed promptly, a number of people could have gone into Rebecca’s bedroom and murdered her and been able to escape swiftly without anyone having known. But if a person or a group of people did this, why did they do it? Could it have been because of her family’s reputation?4

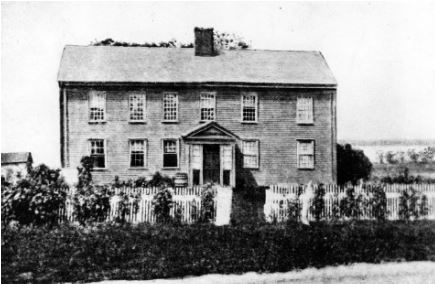

Thomas Cornell Sr. and Rebecca Cornell lived in Portsmouth, Rhode Island, along with their four daughters and three sons. They formerly lived in Boston, where they had planned to stay for the rest of their lives when they arrived from England in 1627. Thomas Sr. and Rebecca Cornell bought a house and 112 acres in Boston from William Baulston, a settler who abandoned Boston to go to Portsmouth, a new settlement Rebecca’s brother, John Briggs, along with other settlers had found.5 In 1640, Thomas Sr. and Rebecca Cornell’s family decided that it was best to leave Boston and move to Portsmouth due to a number of fines Thomas Sr. had received. The fines consisted of drinking heavily at the pinnace, selling wine without a licence, and selling beer above the maximum allowable price. As soon as they arrived in Portsmouth they were welcomed, and they immediately made Thomas Sr. a freeman meaning he was able to purchase land in Portsmouth and within a year Thomas Sr. had been granted meadow land and made constable of Portsmouth. In the next couple of years, Thomas Sr. prospered in Rhode Island. The Governor Kieft of New Netherlands awarded Thomas a tract of land in 1646, seven months before the town of Portsmouth allotted him 100 acres of land where his widow would meet her tragic death more than a quarter century later.6

The jury was wrong in accusing Thomas for the murder of his own mother. However, the jury’s information about Thomas that led to his conviction was mainly based on Thomas’s relationship with his mother. Their relationship was filled with bitterness and hatred that was badly fueled with financial conflict.7 Despite Thomas living in his mother’s household, Rebecca made Thomas verbally pledge that he would pay rent to her while also providing and paying for a maid to take care of her during her remaining years.8 To continue this bitter relationship, in Rebecca’s will, all of her estate was to be equally divided among her children, whom she listed by name. All of her sons and daughters received a part of Rebecca’s property, such as clothes, valuable objects, and even one of her daughters, Mary, inherited her mother’s gold ring. All the children except for Thomas was mentioned in Rebecca’s will. Even Thomas’s first wife was mentioned in her will. This was because Thomas was the only son living with his mother, along with his wife whom Rebecca loved. Unfortunately, Thomas’ wife died a couple years after Rebecca signed her will. Shortly after, Rebecca was asked as to why she did not live with any of her other children. She said that if she knew Thomas’ wife was going to pass, she would have left years ago.9 This shows how bitter Thomas’ relationship with his mother really was. Despite their relationship, this does not mean that Thomas necessarily murdered his own mother. Almost every human beings argues with their mother, its just what we do; however, we don’t go and murder our own mothers.

Although the case of Thomas Cornell was closed, it was never solved. The jury found Thomas guilty of murdering his mother, but his decision was not certain. The testimony suggests that Thomas had the opportunity to kill his own mother; however, that doesn’t necessarily mean he did. There was no one there to see the death of Rebecca, nor was there a murder weapon found at the scene. To this day, this mystery has not found the proper reason as to what happened to Rebecca Cornell for her tragedy on February 8, 1673.

- Cornelia Hughes Dayton, “Getting Beyond ‘Who Done It,'” in Common-Place (2003): 1. ↵

- Elaine Forman Crane, Killed Strangely: The Death of Rebecca Cornell ( Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2002), 114. ↵

- Cornelia Hughes Dayton, “Getting Beyond ‘Who Done It,'” in Common-Place (2003): 1. ↵

- Elaine Forman Crane, Killed Strangely: The Death of Rebecca Cornell ( Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2002), 114. ↵

- Elaine Forman Crane, Killed Strangely: The Death of Rebecca Cornell ( Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2002), 61-62. ↵

- Elaine Forman Crane, Killed Strangely: The Death of Rebecca Cornell ( Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2002), 65. ↵

- Elaine Forman Crane, Killed Strangely: The Death of Rebecca Cornell ( Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2002), 106. ↵

- Cornelia Hughes Dayton, “Getting Beyond ‘Who Done It,'” Common-Place (2003): 1. ↵

- Elaine Forman Crane, Killed Strangely: The Death of Rebecca Cornell ( Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2002), 79-80. ↵

69 comments

Felicia Stewart

This article was a great read, I really enjoyed it! I think it is interesting how they did not have much evidence on if he did, or did not, murder his mother. However, the jury still found him guilty. Also, a point that you brought up that I thought was interesting, was how everyone except for him was in the will. Personally, I believe this would give reason as to not killing her, he would not be getting anything out of it anyway other than a potential death sentence.

Alicia Guzman

This is a very interesting article. I have never heard of this incident. I find this to be tragic as well. It seems to me any major crime committed before DNA technology and forensic science tactics are kind of baseless and a shot in the dark. Just because someone’s relationship with someone is not positive it does not mean they would kill the person and to base a whole crime on that is a complete miscarriage of justice.

Leeza Cordova

I think for the jury to conclude that he killed his mother because of his relationship with her is a bit extensive. I think many people can also agree on the fact that they do not have the best relationship with atleast one parent, but that does not mean that they killed them. Their relationship made me wonder if the hostile behavior of his mom towards Thomas affected him negatively in any way.

Chelsea Alvarez

This is a very peculiar case. After reading this, I can’t really pinpoint if Thomas did or did not kill his mother, but it’s interesting to see that a jury convicted him guilty even when the case remained unsolved. I thought it was very strange that Rebecca had all of her children and Thomas’ wife on her will but not Thomas himself. Although they did seem to have a rough relationship, that is not enough to convict someone of being guilty of murder.

Fatima Navarro

Interesting article. I wouldn’t say that Thomas did or did not kill his mother since I would need more prove and more evidence to backup my claim. However, even if he wasn’t on his mother’s will, that calls for a lot of resentment sometimes, and people do things because of the hatred (some cases have been that way). Nevertheless, it was a good read about a case that may or might not been rightfully deliberated.

Krystal Rodriguez

I really enjoyed this article and the way it painted the picture of Rebecca and her sons relationship. Although they had their arguments and didnt always see eye to eye, he didnt have a real reason to kill his own mother. Its so astonishing that there was no evidence not even a murder weapon to prove who and how Rebecca was killed.

Averie Mendez

I liked that you mentioned that John Briggs was visited by Rebecca’s spirit. Considering that this took place in the 17th century reminds me how Briggs’ claim that he was visited by a ghost was probably considered valid and was genuinely considered as evidence. It’s humorous if you think if how absurd it would be if someone said that in court in this day and age. Anyways, I really think Thomas might’ve killed his mom.

Danniella Villarreal

It is hard to believe that Thomas would end up murdering his own mother when his name was not even on her will. What would have been his motive? Would he do it just because of their bitter relationship? It is interesting to know that the murder was never truly solved. The jury believed that it was Thomas who murder her but reading throughout the article it really could have been anyone.

Ava Rodriguez

These crime articles are really interesting. Rebecca and Thomas’ relationship did not seem the healthiest but was that enough for him to murder his own mother? While they tried to prove he is innocent, how could we know what really happened? There really was not any evidence against him. The only thing known was their rocky relationship. People kill people they love everyday, and it may be hard to believe but it is still possible. They just need evidence to prove it.

Paola Arellano

Although it is true that there was not a completed investigation on the case and it did not seem to be enough evidence to convict Thomas of the crime, the other ideas are a little farfetched. The ghost story cannot possibly be enough to consider that someone else murdered her. It could completely be a myth or a folktale that the neighbor made up. However, in those times it was more likely to believe a story so outrages as seeing the ghost of a dead woman. The rocky relationship does not help Thomas’s case but there is also no other evidence that he did not kill his own mother.