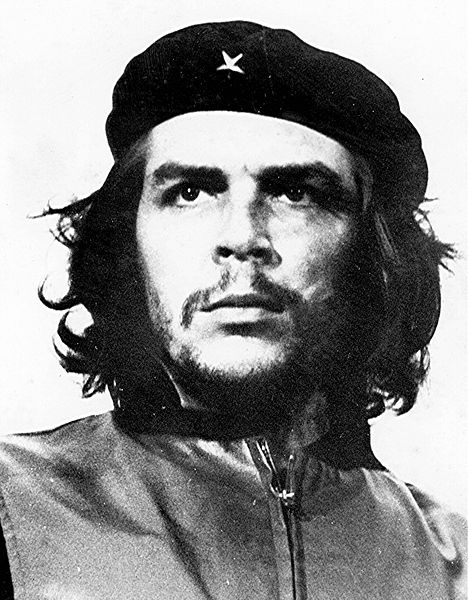

His face is known all over the world. With his long thick hair and charismatic stare, Che Guevara is globally recognized as a symbol for revolution and rebellion. He was the young medical student who sought to free the world not only from disease but also from oppression, poverty, and corruption by any means necessary. Around the world, especially in Latin America, Che Guevara is seen as a hero of the poor. But in other places, such as in the United States, he is regarded as a communist warlord whose radicalism only left chaos. But who was this Che Guevara? And how is it that this Argentinian physician became one of the most polarizing characters in modern history?

Ernesto Guevara was born on June 14, 1928 in Rosario, Argentina. As a child, Guevara suffered from asthma attacks, and he was mostly taught at home by his mother. This is where Guevara’s mental cogs about politics began to turn, for he was exposed to his mother’s radical views, and he also read several controversial leftist works in his family’s library. And at the age of fourteen, Guevara joined the Partido Unión Democrática, an organization that opposed the Argentine dictator Juan Perón. Influenced by his chronic asthma and his grandmother’s death from cancer, Guevara decided medicine was what he wanted to do, and in 1948, he went to the University of Buenos Aires.1

“I dreamed about being a famous researcher. I dreamed of working tirelessly to achieve something that could really be put at the disposal of humanity…” —Ernesto Guevara2

In 1953, Guevara finished his studies and became a physician, but a few years before that, he decided to take a few motorcycle trips around Latin America. The first trip was in 1950, and the second was from 1951 to 1952 with his friend Alberto Granado, a biochemist. The two medical students would travel through Chile, Peru, Colombia, and Venezuela. Guevara then went to the United States by himself, only to be extremely broke before heading back to Argentina.3 It was on this second trip that Guevara and Granado witnessed unimaginable levels of poverty, disease, and hunger. During their time in Chile, Guevara wrote in his diary how the hospitals they visited had filthy operating rooms, poor lighting, limited surgical instruments, and virtually no awareness of hygiene. Compared to Argentina, Chile’s standard of living was low and unemployment was high. Even for those who did work, such as the Chilean miners, the authorities provided them with little protection.4 After Guevara became a doctor, he went on another trip—this time to Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Panama, Costa Rica, and Guatemala.

This third trip only added more inspiration for Guevara to enter the political realm, for he observed the mobilization of workers and reforms in Bolivia following the Bolivian Revolution in 1952. It was then and there that Guevara believed that in order for him to change the world for good, he was going to need more than just medicine.5

In the early 1950s, the world was in the early stages of the Cold War. The two superpowers, the United States and the Soviet Union, each believed that their ways of ordering their economies and politics was the right way, and the rest of the world was forced to join one side or the other. Much like the rest of the world, Latin American countries’ decisions could mean their survival or destruction. This was an especially difficult for time for Latin American countries because many of them were run by their country’s elites or military dictators. Many within those countries saw communism as their solution for liberty, which led the United States to become involved in Latin American affairs, both overtly and covertly, to control its communist potential.6

Take Guatemala: from the 1940s to the early 195os, the natives had their land taken away by the United Fruit Company, an American corporation that had banana plantations in the country. The democratically-elected president Jacobo Árbenz sought big changes in his country, including giving those appropriated lands back to the natives. He was able to redistribute some of the uncultivated lands to the Guatemalan peasants, while compensating the landowners.7 However, in 1954, Árbenz was overthrown by a U.S.- sponsored military coup.8 The United States claimed that they were simply preventing communists from taking private property. After all, they said, Árbenz did embrace Marxist ideas and his government did contain members from the Communist Party. In reality, however, the U.S. was protecting an American company’s profits and the government that replaced Árbenz turned out to be murderous.9

Guevara was actually working in Guatemala as a doctor when this happened. In fact, it was in Guatemala that he earned the nickname “Che,” which roughly translates as “hey you.” However, when Árbenz was overthrown, Guevara was shocked and sought refuge in the Argentinian embassy. Guevara witnessed not only just how powerful the United States was, but also how imperialistic and intimidating it was. How can a country that believes in democracy and freedom aggressively attack a smaller nation? For the next two months, still in the embassy, Guevara studied all he could find on Marxism. However, no matter how much he studied, Guevara felt there was no hope to further change Guatemala from its current state.10 From the embassy, Guevara escaped to Mexico City, where he would continue studying Marxism and eventually meet Cuban revolutionaries Fidel and Raul Castro.11

Marxist theory is a collection of economic, social, and political ideas developed by German philosopher Karl Marx.12 This theory has been used in labor, anti-colonial, feminist, civil rights, and environmental movements. Although it can be used in a variety of movements, Marx was specifically interested in the behavior of industrial capitalism. He observed that the wealth produced by a factory was made possible by the workers who worked for long hours for little pay. However, only a few, such as the factory owners, benefited from most of this wealth creation, while the workers were left impoverished.13 What Marxist theory provides is an alternative to this capitalist process. In Marxist vocabulary, the capitalist elite is called the bourgeoisie and the workers are called the proletariat. Because of the class conflict inherent in the process of capitalist production, Marx predicted that the proletariat would overthrow the bourgeoisie.14 In fact, the objective of Marxist theory is to overthrow the bourgeoisie, establish a dictatorship of the working class, and begin the process of communism, where, ideally, wealth is distributed evenly to everybody. Once in charge of the state, the proletariat will be able to transform the oppressive nature of the state and replace it with an organization that administers the coordination of society’s production, or “the administration of things.” The state structure of oppression will then “wither away” and humanity will enter an egalitarian society and live according to the Marxist phrase “from each according to his abilities—to each according to his needs.”15 This would be the communist stage that Marx envisioned as the necessary resolution of the class conflicts of the capitalist stage of development. There would no longer be rich and poor—there would no longer be social oppressions of any kind. However, in order to establish that classless society, the proletariat must first create a revolution to seize power from the bourgeoisie.

After the replacement of Árbenz, Guevara believed that the U.S. was his enemy and presumed that it was vital to destroy the agents of capitalism and imperialism. When he met Fidel and Raul Castro, he agreed to help them overthrow the U.S.-backed dictatorship in Cuba.16 In 1956, Guevara and eighty-two other fighters, guerrillas, sailed to Cuba, determined to overthrow the dictator Fulgencio Batista. However, once they arrived, they were ambushed and half of the group was instantly killed. In the midst of the ambush, Guevara was left with two things to choose: a first-aid kit or a box of bullets. With adrenaline flooding him and the will to survive, he chose the box of bullets.17 It was there, on that Cuban beach, that Che Guevara was no longer some ordinary doctor. Rather, he converted to a guerrilla fighter, who would not let anything stand in his way, even if it means killing others.

After fleeing to the Sierra Maestra mountains, the remaining guerrilla fighters had to reformulate their mission. For the next two years, they recruited peasant farmers and other Cubans to join their cause.18 With strategic and swift lightning raids, they gradually crushed Batista’s forces. In December 1958, fighters under the command of Guevara invaded the city of Santa Clara. Hearing this news, Batista feared his defeat was unavoidable, and so he fled to the Dominican Republic. On January 8, 1959, Cuba was now in the hands of the Castros and Guevara.19

The overthrowing of Batista wouldn’t have been possible without the utilization of guerrilla warfare. Derived from the Spanish term for “little war,” guerrilla warfare describes the tactics small groups can use against bigger, typically better-equipped, forces. Usually, guerrilla fighters rely on tactics such as ambush, espionage, and sabotage. By no means is guerrilla warfare a new concept. During the American Revolution, the colonists learned from the natives to hide in dense forest regions and attack the British army by surprise. In World War II, guerrilla (or underground) forces in France fought against Nazi occupation. Other examples include the American Civil War, the Chinese Civil War, and the Vietnam War.20

In 1961, Guevara’s handbook, Guerrilla Warfare, was published. In it, he describes how the Cuban rebels were able to be so successful. He writes that it is not necessary to wait for all the ideal conditions for a revolution to occur. Especially when it comes to colonialism or imperialism, Guevara mentions certain things can create fertile ground for revolution and that guerrilla fighters, with lightning speed, can engage against weak government forces. This can be accomplished easily in rural regions since government forces are weaker there than in cities.21 Guevara writes not only about how guerrilla warfare works, but also how to create a revolution, and that it is possible for popular forces to win a war against an army bigger than them. 22 Guevara’s work would become a sort of manual for organizations such as the guerrillas of the Argentine Workers Revolutionary Party, the Sandinistas in Nicaragua, and the Zapatista Army of National Liberation in Mexico.23

In Cuba, Guevara was responsible for setting up medical clinics and taught peasants how to read. In fact, over time, the literacy rates in Cuba rivaled that of the United States and western European countries.24 He would also draft a law that redistributed land to the people.25 Under the new Castro government, all Cubans now had access to jobs, medical care, and free education.26 Although everyone had food to eat and a roof over their head, Cuba never became a paradise.

Although there was no longer poor and rich, it did not mean that the Cubans were living in a utopia. Cubans still lacked certain freedoms, such as speaking against the government or traveling outside the country. Under Fidel Castro’s regime, they tried and executed 483 people, mainly Batista’s supporters, in the span of three months.27 Castro would also often purge anyone who would speak in favor of policies he disagreed with.28 Not only did Cuba lack liberty, but it also lacked a stable economy, because Guevara assumed positions for jobs he had no expertise in. Although he tried to reestablish Cuba’s economy, Guevara ultimately couldn’t, due to the lack of sufficient money for development, the lack of established markets, and lack of advanced technology.29 Essentially, Cuba replaced one dictator with another, and so many Cubans secretly left, hoping to find freedom elsewhere. Sadly, the people Guevara was trying to help and save, ended up fleeing from him and so his dream for Cuba resulted in failure.

Although Guevara never accomplished his goal for a fair and just world, many see him as a paragon for standing against goliathan forces. However, there is also evidence that Guevara was a criminal, since he was involved in the creation of Cuba’s new notorious dictatorship. Guevara started with worthy intentions, yet when did he cross the line from being a moderate individual to a radical? What was the spark that led this physician to become a fighter for revolution? With multiple events, such as his motortcycle trips and the attack in Guatemala, did Guevara become a radical abruptly, or was it more subtle? The story of Che Guevara is a testament to humanity that reveals to us that history is a spectrum of perspectives and that anyone has the potential to transform into a radical.

- Contemporary Hispanic Biography, 2003, s.v. “Guevara, Ché (Ernesto): 1928-1967: Revolutionary Leader,” by Kari Bethel. ↵

- Ernesto “Che” Guevara, The Motorcycle Diaries: Notes on a Latin America Journey (Melbourne: Ocean Press, 2003), 167. ↵

- Encyclopedia of Activism and Social Justice, 2007, s.v. “Guevara, Che (1928-1967),” by Gary L. Anderson. ↵

- Ernesto “Che” Guevara, The Motorcycle Diaries: Notes on a Latin America Journey (Melbourne: Ocean Press, 2003), 87. ↵

- Encyclopedia of Activism and Social Justice, 2007, s.v. “Guevara, Che (1928-1967),” by Gary L. Anderson. ↵

- John C. Chasteen, Born In Fire & Blood: A Concise History of Latin America 4th ed. (New York: W.W Norton & Company, 2016), 275. ↵

- John C. Chasteen, Born In Fire & Blood: A Concise History of Latin America, Fourth Edition (New York: W.W Norton & Company, 2016), 279. ↵

- Encyclopedia of Activism and Social Justice, 2007, s.v. “Guevara, Che (1928-1967),” by Gary L. Anderson. ↵

- John C. Chasteen, Born In Fire & Blood: A Concise History of Latin America, Fourth Edition (New York: W.W Norton & Company, 2016), 279. ↵

- Contemporary Hispanic Biography, 2003, s.v. “Guevara, Ché (Ernesto): 1928-1967: Revolutionary Leader,” by Kari Bethel. ↵

- Encyclopedia of Activism and Social Justice, 2007, s.v. “Guevara, Che (1928-1967),” by Gary L. Anderson. ↵

- Encyclopedia of Activism and Social Justice, 2007, s.v. “Marxist Theory,” by Gary L. Anderson. ↵

- Encyclopedia of Communication Theory, 2009, s.v. “Marxist Theory,” by Ronald Walter Greene. ↵

- Encyclopedia of Communication Theory, 2009, s.v. “Marxist Theory,” by Ronald Walter Greene. ↵

- Encyclopedia of Political Science, 2011, s.v. “Withering Away of the State”; Karl Marx, “Critique of the Gotha Programme,” in Marx: Later Political Writings, ed. Terrell Carver (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 214-215. ↵

- John C. Chasteen, Born In Fire & Blood: A Concise History of Latin America Fourth Edition (New York: W.W Norton & Company, 2016), 284. ↵

- Encyclopedia of Activism and Social Justice, 2007, s.v. “Guevara, Che (1928-1967),” by Gary L. Anderson. ↵

- Global Events: Milestone Events Throughout History, 2014, s.v. “Che Guevara Publishes Guerrilla Warfare,” by Jennifer Stock. ↵

- Global Events: Milestone Events Throughout History, 2014, s.v. “Che Guevara Publishes Guerrilla Warfare,” by Jennifer Stock. ↵

- Encyclopedia of Espionage, Intelligence and Security, 2003, s.v. “Guerrilla Warfare,” by María López. ↵

- Global Events: Milestone Events Throughout History, 2014, s.v. “Che Guevara Publishes Guerrilla Warfare,” by Jennifer Stock. ↵

- Encyclopedia of Espionage, Intelligence, and Security, 2003, s.v. “Guerrilla Warfare,” by María López. ↵

- Global Events: Milestone Events Throughout History, 2014, s.v. “Che Guevara Publishes Guerrilla Warfare,” by Jennifer Stock. ↵

- Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, 2008, s.v., “Castro Ruz, Fidel (1926-2016),” by Michael Powelson. ↵

- Global Events: Milestone Events Throughout History, 2014, s.v. “Che Guevara Publishes Guerrilla Warfare,” by Jennifer Stock. ↵

- Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, 2008, s.v., “Since 1959,” by Jonathan C. Brown. ↵

- John C. Chasteen, Born In Fire & Blood: A Concise History of Latin America Fourth Edition (New York: W.W Norton & Company, 2016), 285-291. ↵

- Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, 2008, s.v., “Since 1959,” by Jonathan C. Brown. ↵

- Contemporary Hispanic Biography, 2003, s.v. “Guevara, Ché (Ernesto): 1928-1967: Revolutionary Leader,” by Kari Bethel. ↵

88 comments

Sydney Nieto

Good article, I’ve never heard of Ernesto Guevara, but he was an interesting person. He got into politics at a young age, which surprised me. It cools how he wanted to get into medicine at the young age and achieve that as he got older. I did find his nickname funny as it translates to “hey you”. It’s interesting how people get their names through history.

Jaedon E

Great article! It is sad when in history class you only talk about a historical figure in less than 5 minutes. When reading what I did find interesting what influenced him to pursue the medical field. Knowing an important figure like his grandmother, and how she died from cancer and then with him having asthma. Being able to not care about himself knowing what all is happening around him.

Barbara Ortiz

Great article. I remember watching The Motorcycle Diaries many years ago, and was fascinated with the “earlier” life of Guevara. Most of us do know him for the revolutionary side and his connection with Cuba and Castro. But either many don’t know or forget about his beginnings as a doctor and someone who really wanted to make an impact, real change for the impoverished people of Latin American countries.

Jared Sherer

This article was interesting to read and I enjoyed reading about both sides of Guevara. I never heard about him until I read this article. It is interesting to say he could be a hero but also a criminal at the same time. Although there is bad about him it also balances out to be some good as well. The author did a good job being informative and keeping me engaged with the article. Learning about his road to becoming a radical was interesting to read about as well as his work for the citizens and how he would help people. Though an interesting and complex man, the article was very well written. It is also compelling to me to consider that good intentions and plans for the formation of a new government, like in Cuba, can be turned to evil in the hands of certain types of people.

Noelia Torres Guillen

This was a well-written article that helped me further understand Marxist-theory, guerilla warfare, and other revolutionary movements. I’ve always been confused as to why such ideals with good intensions, like helping the people giving them free education and free healthcare, failed. It all has to do with power, and the more power you get the more and more you want. I loved the last thing you said “history is a spectrum of perspectives”. This is so true because history is so complex and this article really did prove how complex it is.

Anna Steck

I liked that you highlighted the reason that communism becomes popular- as a response to poverty. In the background of Guevara’s story, that rings true. I also really liked your lexicon. It sounded very personal and at times casual. This really emphasized the story telling feel. It was also more detailed then most articles I have read- it described Marxism briefly as well as guerilla warfare. This made the article clear and added some nuance. Very well done.

Adelina Wueste

This article was very well written! You provided a great amount of detail as well as background information. I really liked how you ended the article with questions and how you also included a video. I think it’s very interesting how Che Guevara’s main goal was to help people, especially those in poverty an unjust circumstances. I also found it very interesting how in Guevara’s book he wrote about how people don’t have to wait for a perfect time to start a revolution. I found that interesting because I would think that revolution leaders look for perfect times to start one, but I can also see where perfect timing doesn’t necessarily exist.

Eugenio Gonzalez

The article’s compelling narrative maintains the reader’s attention with Ernesto ”Che” Guevara’s upbringing. Before reading the article, I had never known about Guevara’s background and how her mom’s views influenced him. It is incredible how the military coup led by the U.S. caused Guevara to flee to Mexico City, where he would meet Fidel and Raul Castro. The author does an excellent job of demonstrating the transformation of Guevara from an ordinary doctor to a guerilla fighter.

Azeneth Lozano

What a well-written and well-worded article with facts about Che Guevara that I have never heard of. Its not every day you hear that a medical student and doctor convert to a guerrilla fighter. As mentioned in the article, he was seen as a “hero to the poor” and helped peasants all over Latin America in moving forward with technology and education. Overall, I like how you laid out the article by not only providing one side of the story. The article contained both the United States and Latin American viewpoint on Che Guevara.

Melyna Martinez

The article is very interesting on how Che Guevara became a symbol of resistance even if the ending was him dying young, his impact stayed forever. He has brought on a such change to Latin America with his want for change in poor communities to being a guerilla fighter. One thing that did stick out to me was how he was a doctor before he became a political figure, but everything he saw made him want to change in Latin America.