Children today spend five days a week going to school for eight hours. During the first half of the nineteenth century in Britain, this was not the case. Instead, children even as young as five or six would toil all day long in factories or in mines. They had no breaks, no time off, and no schooling. Their work often led to horrible accidents, children being injured for life, and children left without an education.

Children laboring, of course, did not start with the British Industrial Revolution. It had been a normal part of life in Europe since the middle ages, when children helped their parents on farms and with household work. The people’s perception of this work, however, changed during the Industrial Revolution, since that is when people began to see this new kind of labor, factory labor, as an injustice and even criminal.1

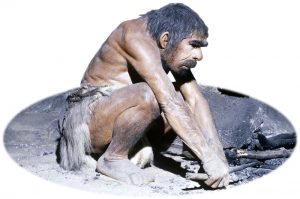

The Industrial Revolution began in Britain during the 1780’s and rapidly changed the work process and the social relations of work. Prior to the Industrial Revolution, most people worked directly in the production of food, usually as farmers on their own farms. When textile factories began forming in the new factory cities, instead of working on their farms and making what their family needed, people left their farms and moved into the factory cities to make a living. Factory conditions of work, however, were far different from the work rhythms of farm life. In fact, they were brutal in comparison. Factory workers would typically put in between 12 and 16 hour days, working for meager wages. The machines they attended were dangerous, and the workers were often on their feet throughout the day, with perhaps a half-hour break for meals. Among these workers were children, many of whom were as young as five or six years old. Children were valued as workers for their small stature and ability to climb into small places and do things that adults often could not do. This often resulted in mutilation and the loss of appendages for many of these children.2

Children were also valued as workers by the factory owners because of the low wages that they were paid. Men were paid the most in factories, followed by women and then children. These wages, however small, were needed by the families of these children simply to survive. The parents often sent their children out to work to help pay for rent, food, and otherwise help make ends meet.3

One reason that the British public became outraged by child labor practices was the fact that children in factories were not receiving an education. Horace Mann, an American educational reformer, stated:

No greater calamity can befall us as a nation than that our children should grow up without knowledge and cultivation. If we do not prepare them to become good citizens, develop their capacities, enrich their minds with knowledge, imbue their hearts with a love of truth and all things holy, then our republic must go down to destruction as others have gone before it.4

This represents the thoughts of the British at the time, which was being echoed in the United States during its own industrial revolution. People wanted to ensure the future of their nation, which starts with the young. They believed that children should attend school for at least a while.5 This led to several laws being passed to raise the legal age of work.

In 1833, the British Parliament passed the Regulation of Child Labor law to help improve the working conditions for children in factories. The Law limited the age of workers, saying that they had to be older than nine with an age certificate to prove it, and that children 9-13 could not work for more than nine hours a day. Additionally, children 13-18 were not permitted to work longer than twelve hours a day. Along with these work-hour restrictions, the law also made school attendance a two-hour requirement, and said that children could not work at night. Fines for breaking these rules were small, however, so they were frequently violated, often with impunity.6

Many other pieces of legislation were also passed to place limits on the gender, hours, and ages of workers. The Mining Act of 1842 prevented women and girls from working in mines, and the Ten Hours Bill of 1847 set ten as the maximum number of daily working hours for women and children. This act was hated by factory owners because they believed it would hurt the textile industry’s competitiveness worldwide. After these bills, others followed to ensure their effectiveness, and to ensure that they would be properly implemented.7

By 1900, the minimum working age had been raised to twelve years of age and child labor had decreased drastically in Great Britain. However, the introduction of legislation against child labor provoked its share of protests as well. Because of these protests, Parliament established commissions to collect evidence of abusive practices. These were called the Blue Books or Sadler Reports. They interviewed children, parents, factory workers, owners, and even doctors on the condition of children in textile factories. Unsurprisingly, the reports uncovered a range of serious abuses by factory owners and overseers. Unfortunately, most critics just said that the claims were exaggerated in order to continue their money making practices.8

The legislation surrounding the British Industrial Revolution had become very effective by 1900, and child labor and its accompanying abuses had decreased dramatically. By 1900, most children were attending school instead of working in factories. The laws passed finally added up to changing British child labor to being closer to what we see today, a mostly child-free labor system, with children going to school and adults having regulated working hours.

- World History Encyclopedia, 2011, s.v. “Child Labor and Child Labor Laws in Early Industrial Great Britain.” ↵

- James D. Schmidt, “Broken Promises: Child Labor and Industrial Violence,” Insights on Law & Society, no. 3 (Spring 2010): 14–17. ↵

- Robert Whaples, “Hard at Work in Factories and Mines: The Economics of Child Labor during the British Industrial Revolution,” Business History Review, no. 2 (2001): 429. ↵

- Friends’ Intelligencer vol. 28 no. 1 (1871): 336. ↵

- James D. Schmidt, “Broken Promises: Child Labor and Industrial Violence,” Insights on Law & Society, no. 3 (Spring 2010), 14–17. ↵

- Great Britain, “Factories Regulation Act” (1833). ↵

- Steven Toms and Alice Shepherd, “Creative Accounting in the British Industrial Revolution: Cotton Manufacturers and the ‘Ten Hours’ Movement,” MPRA Paper, No. 51478 (2013), 6-8. ↵

- World History Encyclopedia, 2011, s.v. “Child Labor and Child Labor Laws in Early Industrial Great Britain.” ↵

141 comments

Sydney Nieto

The Children without a Childhood article was an interesting article to read due to how time passes by many regulations and laws were put into place for child labor. These laws and regulations gave children an opportunity to get an education, they restricted from overworking the children, the amount of labor decreased, and age restrictions were put into places. Overall, good article.

Jose Maria Gallegos Cebreros

Hi Bailey, First of all congrats on the great article! Your article was very informative and I really enjoyed your writing style. I did not know about the topic before but you made it very easy to understand and I think it is very simple, and at the same time informative. I can see that it involved a lot of research to be able to write this article.

Gabriella Parra

I wonder how child labor laws and laws that regulated the working conditions of women affected individual families. If the whole family was working in order to survive, how did a reduction in hours for women and children affect family incomes and standards of living? Were there protests for federal aid because of these restrictions? Even with these struggles, the first child labor laws were a step in the right direction. Especially since they included at least some mandatory education for children.

Jared Sherer

Learning about the hard labored childhood children had to go through during the British Revolution gives me a different view and makes me grateful my childhood was so carefree. The author clearly pointed out good things that came from it like the Child Labor Laws or even how they would stress work and learning how to build and fix things, before education as well. I learned that families would even rely on their child’s income to keep everything in the household going smoothly. Working long hours at the age of 5 years old is insane, hard labor by children for such little pay is something that is hard to wrap your mind around. It was certainly a different world, and hopefully one from which our country (and Great Britain) has learned some hard lessons.

Brandon Vasquez

Great article! I don’t know if we understand how well we have it being able to go to school and do the things we want to do whereas in history things haven’t gone that way for kids. The fact that kids had to go through gruesome work environments is just scary to think about especially with how hard they were worked in some cases losing limbs.

Alanna Hernandez

While peasant children in the mid-evil times might have done back breaking work, at least it was done in the fields with breathable oxygen. The emphasis on the differences in child labor for that time versus this era is definitely needed. This was also the start of the push for education for all children not just the wealthy. As Aristotle believes to live a happy fulfilling life one needs to be educated.

Martina Flores Guillen

The development of the the buisness industry along with child labor is a dark and extensive period of which many children were taken advantage of. Looking at this article, the depiction of the children utilized as a easyer method to maintain a “progress” labour outcome outlines the perspective of pasts and present business objectives. Child Labor during the Brithsh industrial revolution represents a world where child labor is still seen, which shows how much individuals have learned from past mistakes.

Barbara Ortiz

Good article on the Industrial Revolution and the impact felt by children. Despite reforms, we still experience the mistreatment and exploitation of children in the workforce today. I was just reading an article in the newspaper this morning about immigrants under the age of 18 are working in factories in the US because they sponsors are not capable of providing for their means, or they are trying to work for wages to send money back home to their families. In many cases, kids are attending school during the day and working night shifts, leaving them very little sleep.

Jacob Salinas

This was a very interesting article to read about. It is crazy to me that these children would work in factories all day with no breaks and no time off. And to make it worse, these children were as young as five when they started. This was a very organized and well written article that described the history of child labor.

Anayetzin Chavez Ochoa

Yikes! And we complain about school: at least we don’t have to work in back-breaking conditions shortly after we barely learned to speak! I remember learning about people losing fingers and limbs, and some even ending up in the machines as a result of workplace accidents, and it was horrific to learn about (and that was just the adults). Hearing this about children who probably had their favorite toys and their favorite meals getting injured or mortally wounded hurts my heart. They were abused, the poor things, with low wages if any, and used for their size to get the job done! That’s horrible! Thank you for writing this, it was very informative.