Throughout my time as an undergraduate student, I found myself struggling with time management and feeling at home at my university, but I always had my parents to guide me. My parents were my resources when I needed help applying for financial aid, when I had questions about assignments and aided me in constructing a plan to help me ace my classes. Although my parents guided me throughout my undergraduate education, I saw that some of my peers did not have anyone to advise them or lead them to the right resources when they had concerns. Many of my peers were Hispanic, first-generation college students and did not know what resources were available. My parents were both first-generation college students, and my peers’ struggles often reminded me of the stories my parents told me about their time navigating higher education. Despite decades separating my parents’ time at university and my peers’ time at university, the same problems persisted. Time did not establish a better system for Hispanic/Latino students. While I did not go through the same struggles my parents or some of my peers went through to obtain a higher education, I witnessed the emotional, financial, and psychological toll being a Hispanic in higher education placed on them.

Through pursuing an English degree, I was enlightened about the conflicts minorities experience when navigating higher education, specifically Hispanic/Latino students. While confronting a more challenging curriculum and the financial stress that comes with pursuing higher education, Hispanic/Latino students also confront stigmas and racism. In addition to understanding content and submitting assignments, Hispanics/Latinos must advocate for their seat in higher institutions despite already having a place in universities and colleges. In comparison to other ethnicities, “about a quarter of Latinos 25 to 29 (23%) had earned a bachelor’s degree, up from 14% in 2020. A similar share of Black Americans in this age group (26%) had obtained a bachelor’s degree, while 45% of White Americans and 72% of Asian Americans ages 25 to 29 have done so” (Mora). Still, Hispanics/Latinos are a small population in higher institutions, which can be attributed to certain barriers. Overall, “Hispanic groups have, in some cases, yet to attain recognition of the existence of educational barriers for them on campuses” (Escobedo 7). With this research, I will use testimonies from the book Telling to Live (2001), written by the Latina Feminist Group, and other literature, such as George Washington Gomez (1990), written by Americo Paredes, to illustrate the effects of systemic racism on Hispanic students throughout time. Through this research, I will advocate for higher education to alter its system to aid Hispanic/Latino students in succeeding in higher education by supporting their academic and personal development.

Initially, I planned to research Mexican American students’ experiences in higher education, but I found that current research lumps multiple groups together and uses broader terms such as Hispanic and Latino. The term Hispanic is connected to European ancestry, while Latino was derived to include more people from Latin America. Specifically, the term Latino was a direct response to the 1960s. Due to this grouping and labeling, I will include data that centers on both Hispanics and Latinos throughout my research. Since this problem is complex from multifaceted perspectives, I will be using the theories of Gina Ann Garcia and Laura Rendon and historical and literary references throughout this research. This interdisciplinary approach is necessary to learn and understand how discrimination began and how it persists in the 21st century.

While there has been progress in including Hispanic/Latino students in higher education, graduation rates are still low for Hispanic/Latino students. Despite there being an increase in higher education, “[f]or Hispanic first-time, full-time students at four-year institutions, 59% graduate within six years compared to 67% of White students (See Figure 6). At two-year institutions, 32% of Hispanic first-time, full-time graduate within three years, compared to 37% White students” (UnidosUS). Additionally, “Latinos face the widest college completion gap (8 percentage points) at public four-year institutions. For the 2014 cohort, the graduation rate for Latinos at public four-year institutions was 58%, compared to 66% for White students,” showing a lack of consistency between enrollment and graduation (UnidosUS). Although Hispanic/Latino students throughout the United States have graduated from higher education, there is a lack of resources for their educational development. Academic achievement does not mean equal opportunity. Traditional ideals “are less concerned about students themselves and what they get out of their lessons,” which separate students from including their own experiences like racial inequality in higher education (American University School of Education Online).

Hispanic/Latino education history reveals many examples of segregation and discrimination based on race, language, skin color, and classicism throughout time. The case of Romo v. Larid (1925) is one of the first cases in the 20th century where Mexican Americans argued against the “educational segregation and/ or exclusion” that was occurring around the United States (MacDonald). Issues surrounding segregation and exclusion persisted, and in 1968, students in high schools around California held walkouts. These walkouts consisted of Chicano students “demanding better guidance counselors for college, Latino teachers, Mexican American history classes, smaller classes, bilingual classes for those who needed them, and parental advisory board” (MacDonald). During the 21st century, “[a]approximately 1 in 4 Hispanic students reported frequently or occasionally experiencing discrimination, harassment, disrespect, and feelings of being unsafe” despite there being years of advocacy for Hispanics/Latinos in education (Brown). While there are more Hispanic/Latino students in the school system today and instances of blatant racism in and outside of the classroom are fewer, the average populations of Hispanics/Latinos in higher education are still low compared to other ethnic groups. Scholar, Biaggi found that:

According to one survey, Latinos with darker skin color have experienced at least one form of discrimination (such as being treated as less smart or being criticized for talking in Spanish) at a higher rate (64%) than Latinos with lighter skin color (54%). When asked about experiencing discrimination by someone who is also Latino, there is an even bigger discrepancy based on skin color: only 25% of lighter-skinned Latinos report discrimination compared to 41% of darker-skinned Latinos (Biaggi).

If the problem of Hispanics in education has been fixed as many claim it has been, then why is retention still a problem in higher education? If the problem of discrimination and equality has been resolved, why do we not have more Hispanics/Latinos graduating from higher education, and why aren’t percentages even with their Anglo counterparts? It is easy to say improvement equals solutions, but that is not true. The lack of acknowledgment of the place of whiteness in education as the norm and the absence of culture and inclusion prevent Hispanic students from feeling at home in higher institutions and continuing their education. The hardships Hispanic/Latino students face throughout their time in higher education continue to be overlooked by many, continuing their feelings of isolation.

The article, “Whiteness in Higher Education: The Invisible Missing Link in Diversity and Racial Analyses” analyzes how white students, faculty, and systems of education often ignore topics surrounding race. By ignoring these topics or separating themselves from the racial struggles minorities face, “a false sense of both contemporary racial progress while allowing White people to strongly hold a positive sense of their racial selves” is established (Caberea et al.). Whiteness in the education system is often dismissed by educators, administrators, and White students. The lack of racial awareness is thus deemed not a problem for white students or administrations; it is up to minorities to fight against discrimination (Cabrera et al.). This ignorance “relates to the continuing legacy and contemporary manifestations of segregation,” making it difficult for minorities to feel heard or for any further improvement in the education system to occur. Through their study, the authors Caberea et al demonstrate how minority students’ struggles are dismissed or separated by white people. Ignoring minority experiences makes it difficult for the struggles of Hispanic/Latino students to be acknowledged.

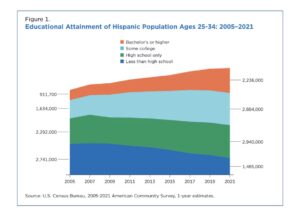

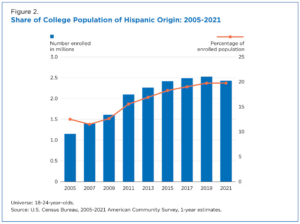

However, more Hispanics/Latinos are applying and being accepted into higher education. As of the 2021 United States Census, “[t]he number of Hispanic people ages 18 to 24 enrolled in college increased to 2.4 million in 2021, up from 1.2 million in 2005” (Hernandez and McElrath). While the Hispanic population in higher education throughout the United States is predicted to increase, retention continues to decrease for Hispanic/Latino students. Despite the current increase, systemic racism encourages Hispanic/Latino students to finish their education by isolating the students from their culture and identity via assimilation, making them feel less than their Anglo counterparts if they indulge in their culture at school. Additionally, there is a lack of resources for Hispanic/Latino students to utilize. Without sufficient support and resources, Hispanic/Latino students are forced to sink or swim in the current higher education system.

The feeling of isolation and discrimination of Hispanics/Latinos in higher education is still lower compared to other ethnicities. It has been found that ‘[i]n 2021, about three-in-ten Latinos ages 18 to 24 (32%) and a lower share among White (37%) and Asian (58%) adults of the same age,” showing how Hispanics/Latinos continue to trail behind in receiving higher education compared to other ethnicities (Mora). This is due to the current structure of the American school system. Despite more Hispanic students being admitted into higher education, the original American school system, which was structured to educate “the Christian religion, train men for the ministry, infuse moral standards, and discipline moral faculties,” is still in place (Rendon 13). Through this original structure, Hispanic students are unable to efficiently learn about their history and feel accepted in higher education.

The alienation of Hispanic/Latino students hinders their continuation of higher education. Michael H. Guerro argues that “[t]his alienation pervades the educational milieu because the pluralistic differences of American society have not found the spiritual and intellectual bonds to unite basic separateness of race, national origin, religion and culture” (Guerro 2). Exclusive parts of the student from the classroom make it difficult for the student to feel accepted in a system that was not built for their benefit. Further, education systems across the United States continue to exclude minority voices. This exclusion is done by separating the students’ lives outside of the classroom from the educational experience, as seen through first-hand accounts from Latinas across the United States in the book Telling to Live.

Telling to Live includes testimonials from Latinas from multi-generations, illustrating the power of confronting the past to prepare future generations for the exclusion they might face because of their culture and begin the path for educational change across the United States. Testimonials are “a novel or novella-length narrative in book or pamphlet (this is, printed as opposed to acoustic) form, told in the first-person by a narrator who is the real protagonist or witness of the events he or she recounts, and whose unite of narration is usually a ‘life’ or a significant life experience” (Beverly 13). In this regard, testimonials capture influential events of a person’s life, allowing minorities to use their voices to bring their experiences and their communities’ experiences to life. The authors in Telling to Live use their voices to focus on their experiences in the United States education system as Hispanic/Latina women. These women illustrate why it is essential to include minority cultures in higher education through their personal stories.

The Latina Feminist Group argues that testimonials have “been critical in movements for liberation in Latin America, offering artistic form and methodology to create politicized understandings of identity and community” (The Latina Feminist Group 3). The Latina Feminist Group’s testimonials highlight the experience of many Hispanic/Latina women in the United States education system. Discussing their experiences, the Latina Feminist Group created an understanding of the barriers currently hindering all Hispanics/Latinos from pursuing and continuing higher education. Through their testimonials, the Latina Feminist Group identifies specific instances in the educational experience that influenced them in higher education and the work environment. Providing specific examples reveals the lack of resources for minority communities and the discrimination that continues to impact minorities’ experiences throughout their time in education.

Norma E. Cantu’s experience with educators created self-doubt in her ability to succeed in higher education. “Getting There Cuando No Hay Camino” centers on Cantu’s experience navigating higher education as a Latina. Cantu set her feelings aside when experiencing discrimination in higher education, forcing herself to stay silent against these oppressive tactics. Instead of speaking up, Cantu “overlooked the racist history lessons and the condescending sexist male professors,” which subjected her to racism throughout her time in higher education (Cantu 63). Ignoring the comments did not make the discrimination disappear; it only taught Cantu to be silent and thus be accepted by peers and educators. Discrimination eventually prevented Cantu from being accepted into programs, which further hindered her self-confidence. These rejections and past treatments from higher education staff made Cantu “believe it’s that I’m not good enough or smart enough” (Cantu 64). Acts of discrimination showed Cantu that she was less valued than her white peers. Without a support group, Cantu’s perspective on her own abilities was affected, creating distrust in herself.

Cantu also highlights the financial struggles many Hispanic/Latino students experience in higher education. For Cantu, her parents “were unable to help with even these [shoes, bus tickets, lunch] minimal expenses,” which influenced her performance in her classes (Cantu 63). Cantu states that “[b]ooks were always a problem, and often would go through a whole semester borrowing and making do without a textbook” (Cantu 63). Financial stress continues to impact college students throughout the United States. The study “A qualitative examination of the impacts of financial stress on college students’ well-being: Insights from a large, private institution” found that “[s]tudents with financial stress primarily reported challenges with their academic studies and social lives” (Moore et. al). The financial stress Cantu faced continues to impact college students around the United States. This problem has and will continue to influence minorities in continuing their education. Additionally, several other factors, such as lack of resources, language barriers, and lack of community, play a role in how minorities experience education.

Another testimonio written by Aurora Levins Morales reveals how there continues to be a lack of resources for Hispanics/Latinos to utilize. In “Certified Organiza Intellectual,” Morales expressed that—at the time—she felt that the only way to be accepted into the education system was to abandon her culture and assimilate into American culture, adopting values and teachings like that of Anglo society. The idea of forgetting her culture affected her initial goal when entering higher education: learning more about the history surrounding Latinas. As Morales worked toward understanding the “history for Latinas,” this was a struggle since there were no resources available for Morales’ research (Morales 31). Specifically, Morales was focused on feminist theory, but the theory she “tried to read in graduate school was written in rooms whose doors were too narrow,” requiring Morales to leave her “deepest intellectual passions outside” of her education (Morales 31). Morales’ experience forced her to rethink her position in higher education, and she felt the need to assimilate in order to gain an education.

Additionally, feeling the need to assimilate affected Morales’ perceptions of her own intellectual capabilities. Morales states that while shaping herself to fit into the current higher education system, her trust in herself felt “under assault,” showing how emotionally detrimental the current education system is to minority students (Morales 32). Excluding potential areas of study or open discussion about multicultural studies shapes the way individuals think about themselves and their community, especially when there is a lack of education surrounding minority communities. While Morales continued her education, it was not until she found a community and open space to openly discuss her experiences that Morales was able to experience a new form of education. This open community allowed an education that many in the community felt “were never acceptable anywhere else,” showing how education excludes minority experiences (Morales 32). Morales’ experience with finding a community of Latina women allowed her and others to reconstruct their identity without traditional educational ideals restricting their experiences and education.

George Washington Gomez, written by Americo Paredes, uses the character Gualinto to illustrate the hardships surrounding Hispanics in the United States education system as well. Gualinto is a Mexican American student in Texas who navigated that education system during the early 20th century. Gualinto’s primary education was rife with racism, almost preventing him from continuing as he was questioning his place and right to an education. Teachers treated Gualinto with little respect, indicating they did not expect much from their Mexican American students. While readers are not given insight into Gualinto’s experience in higher education, he comes back differently than before he left for college. Those outside of his family and childhood relationships call Gualinto by his legal name, George, erasing his connection to his Mexican heritage and allowing for an easier separation from his culture. Additionally, Gualinto does not return home once he graduates college. Instead, he takes career opportunities far away from his childhood home (Paredes). Gualinto’s resistance to return home and go by his family nickname suggests that he wants nothing to do with his culture.

Although it can be easy to condemn Gualinto’s actions, Gualinto made certain decisions to survive the United States education system of the time. Some of these decisions included speaking in “a different tongue,” depending on his location, to help him fit in with those around him (Parades 83). Additionally, the system was not structured to aid those coming from minority backgrounds and forced students to choose between receiving an education or having a connection to their culture. This is shown through the ranking of grade levels for Mexican American students. These “low” and “high” grade levels created additional steps for Mexican Americans to reach graduation and eventually higher education (Parades 83). The barriers Gualinto faced throughout his education continue to affect Hispanic/Latino students in current higher education, although there has been some change in the education system. Lack of awareness and discrimination persist, and literature such as George Washington Gomez highlights the effects of discrimination for Hispanics/Latinos in higher education. Instead of merging culture and education, Hispanics/Latinos are forced to choose between self-identification and success.

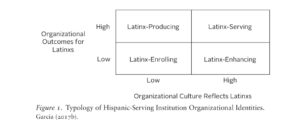

The current education system in the United States needs to be reevaluated for the benefit of Hispanic/Latino students and other groups in higher education. Gina Ann Garcia identifies some barriers for Hispanic students in her book Becoming Hispanic-Serving Institutions: Opportunities for College and Universities. Garcia argues that socialization, unequal access to resources, and white ideologies hinder minoritized students from graduating, influencing their self-identity and confidence throughout their careers. Garcia argues that there is a need for institutional reform to combat these barriers (Garcia). While Garcia specifically focuses on HSIs (Hispanic Serving Institutions), she calls all higher institutions to action. Programs surrounding justice and equity, including staff focused on justice and liberation, bilingualism, and extensive financial aid assistance, are some countermeasures Garcia describes as solutions to creating a more welcoming community and environment for minority students (Garcia).

Currently, our education system is structured around Western philosophers who “assumed that intellectual training and rationality alone were key for understanding” (Rendon 131). Instead of incorporating cultural background, students have been forced to leave part of their identity behind. As Rendon found in her book Sentipensante (sensing/thinking) Peadagogy, the education system must include cultural background to help Hispanics/Latinos excel in higher education. Incorporating “the inner and outer landscape of teaching and learning” combats traditional Western educational practices (Rendon 7). The inner landscape embraces emotions and personal experiences in the classroom, something most students have not experienced while in the education system (Rendon 7). In comparison, the outer landscape focuses on academics and learning skills, excluding the students’ experiences (Rendon 7). While establishing learning skills is needed to help the students’ academic development, there needs to be more inclusion of the inner landscape in the education system, especially since Hispanics/Latinos come from marginalized backgrounds and do not have the resources for their academics outside of their immediate education.

Including the inner landscape will help Hispanic/Latino students feel heard by their institutions since “[m]any Hispanic students being formalized schooling without the economic and social resources that many other students receive, and schools are often ill-equipped to compensate for their initial disparities” (Schneider et al.). Discrimination and racism have created a system working against Hispanic/Latino students. Still, with changes in the curriculum, campus-wide activities, and support from administration and professors, Hispanic/Latino students will be able to feel included in higher institutions, guiding them to graduation. The strategies will not develop overnight solutions, but implementing them into the current system will encourage Hispanic/Latino students to continue their education and find a community within their institutions. In continuing education, Hispanics/Latinos will gain skills to support them in their professional careers and change the trajectory of their families’ lives.

As I take on my next chapter in law school, I cannot help but wonder what resources will be there for me and other minority students. How is the school prepared for me and other first-generation students who have never reached this type of higher education? Now that I am more aware of the obstacles higher institutions must overcome to engage the full student, I am intrigued to look at how law schools have adapted because of Hispanic/Latino students. While “Hispanic/Latinz students comprised 9.4% of both 2023 and 2022 matriculants, compared to 8.8% in 2021,” there is still a major gap between them and other ethnicities in law school (Leipold). As I have discovered through my research, the stages between acceptance and enrollment in higher education are exponentially different. Although my research focuses on undergraduate studies, there still needs to be a focus on this difference throughout graduate schools. If we want to see more Hispanics/Latinos in higher education, we need to take the steps to keep them there. Offering financial, emotional, and educational support will aid Hispanics/Latinos in continuing their education. Confronting systemic racism and discrimination can be a challenge, but each step toward acknowledging the differences Hispanics/Latinos face in higher institutions will create a safer environment for Hispanics to learn more about themselves and their studies.

Works Cited

American School of Education. “Traditional Vs. Progressive Education | American University.” School of Education Online, 17 Apr. 2023, soeonline.american.edu/blog/traditional-vs-progressive-education.

Beverly, John. “THE MARGIN AT THE CENTER: ON ‘TESTIMONIO’ (TESTIMONIAL NARRATIVE).” Modern Fiction Studies, vol. 35, no. 1, 1989, pp. 11-28 JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/26282979. Accessed 6 May 2024.

Biaggi, Hector. “What Isn’t Talked About When We Talk About Latinos.” The Education Trust, 12 Oct. 2023, edtrust.org/the-equity-line/what-isnt-talked-about-when-we-talk-about-latinos.

Brown, Courtney. “One-quarter of Hispanic students face discrimination, leading many to consider leaving college.” Lumina Foundation, 27 Sept. 2023, www.luminafoundation.org/news-and-views/one-quarter-of-hispanic-students-face-discrimination-leading-many-to-consider-leaving-college.

Cabrera, Nolan, et al. “Whiteness in Higher Education: The Invisible Missing Link in Diversity and Racial Analyses.” ASHE Higher Education Report, vol. 42, no. 6, 2016, pp. 7-125, https://doi.org/10.1002/ache.20116. Accessed 6 Mar. 2024.

Cantu, Norma E. “Getting There Cuando No Hay Camino.” Duke University Press, 2001, pp/ 60-68.

Escobedo, Theresa Herrea. “Are Hispanic Women in Higher Education the Nonexistent Minority?” Educational Researcher, vol. 9, no. 9, 1980, pp. 7-12 JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1175569. Accessed 16 Mar. 2024

Garcia, Gina Ann. Becoming Hispanic-Serving Institutions: Opportunities for College and Universities. JHU Press, 12 Mar. 2019

Guerra, Manuel H. “The Retention of Mexican American Students in Higher Education with Special Reference to Biculutal and Bilingual Problems.” College State College, May 1969, files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED031324.pdf.

Hernandez and McElrath. “Gain in Educational Attainment, Enrollment in All Hispanic Groups, Largest Among South American Population.” Census.gov, 10 May 2023, www.census.gov/library/stories/2023/05/significant-educational-strides-young-hispanic-population.html

Lepoid. “Incoming Class of 2023 Is the Most Diverse Ever, But More Work Remains | the Law School Admission Council.” LSAC, 15 Dec. 2023, https://www.lsac.org/blog/incoming-class-2023-most-diverse-ever-more-work-remains

MacDonald, Victoria-Maria. “Demanding their Rights: The Latino Struggle for Educational Access and Equity.” American Latino Theme Study: Education (U.S. National Park Service). www.nps.gov/articles/latinothemeeducation.htm.

Mora, Lauren. “Hispanic enrollment reaches new high at four-year colleges in the U.S., but affordability remains an obstacle.” Pew Research Center, 7 Oct. 2022, pewrsr.ch/3ei5NBh.

Morales, Aurora Levins. “Certified Organic Intellectual.” Duke University Press, 2001, pp. 27-32.

Moore, Andrea, et al. “A qualitative examination of the impacts of financial stress on college students’ well-being: Insights from a large, private institution.” SAGE open medicine vol. 9 20503121211-18122. 22 May. 2021, doi: 10.1177/20503121211018122

Paredes, Americo, George Washington Gomez: A Mexicotexan Novel. Arte Publico Press, 1990.

Rendon, Laura I. Sentipensante (Sensing/Thinking) Pedagogy: Education for Wholeness, Social Justice and Liberation. Stylus Press, 2008.

Schneider, Barbara, et al. “Barriers to Educational Opportunities for Hispanics in the United States.” Hispanics and the Future of America – NCBI Bookshelf, 2006, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK19909.

The Latina Feminist Group. Telling to Live: Latina Feminist Testimonios. Duke UP, 2001.

UnidosUS. A Look Into Latino Trends in Higher Education: Enrollment, Completion, and Student Debt. 2022, pp. 1-4. unidosus.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/unidosus_latinotrendsinhighered_revision.pdf.

4 comments

Silvia Benavides

Wonderfully written article .Thank you for bringing awareness to the systemic barriers people face in their everyday lives.Many like myself relate to these problems

Silvia Benavides

Wow, very eye-opening article. Although many have not experienced the very tough reality of racism in higher learning, I do believe these experiences are well-understood to be occurring, sadly. My sister who is in medical school in the state of Iowa, always mentions that as a Hispanic woman, there is often microaggressions towards her that make it difficult to continue. I do think this topic deserves a spotlight to underscore the importance of this conflict.

Gaitan Martinez

I personally have never dealt with racism, well I have seen a slight subtle racist remark, but it’s never escalated to a high conflict, but I guess I’m lucky. My brother-in-law is back and my sister tells me he does deal with racism every now-and-then, and it makes me angry and sad at the same time. My sister told me this one time he was taking a course, and his professor kept picking on him and accused him of cheating on a test one time! Even though everyone was telling him to report the racist professor, he decided not to and just leave it alone. I’m sure others have thought the same way; in turn, because they, “leave it alone,” the professor still gets away with it.

Nicholas Pigott

Hi Marisabel! This is an excellent informative article with a purview of how it’s like to be under the struggles of a systemic problem. As a white person, I’m privileged enough to not have to experience these sorts of problems, but it’s time people like me find the empathy to help the people beaten down by this system. I completely agree with your assessment and support any means to achieve those goals. Great work!