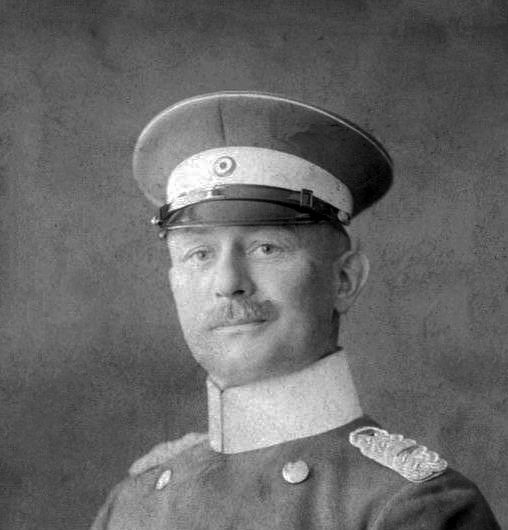

The First World War is mostly known for static trench warfare set mostly on the European continent. However, the war spread to its colonies and its many spheres of influence that also quickly became involved in the affair. Colonial warfare during WWI was very fluid and comprised of skirmishes, guerrilla tactics, and special forces operations with the occasional significant engagements. One of those engagements was the East African Campaign, which started near the beginning of the war and lasted all the way to the end of the war. Here is the story of that campaign from the Germans’ perspective and from the men who led them, namely that of a German General named Paul Emil von Lettow-Vorbeck. He was the German equivalent to Lawrence of Arabia and was as effective. Lettow-Vorbeck is regarded as one of the greatest guerrilla tacticians in military history, and a father to modern-day special forces.

Lettow-Vorbeck came from a small, noble Pomerania household. Coming from a family with a military tradition, he joined the Prussian Cadet Corps. Lettow-Vorbeck went to the military academies at Potsdam and Berlin, where he graduated in 1890 top of his class. He then entered into the Imperial German Army, the “Deutsches Heer.” Lettow-Vorbeck took part in the German expeditionary forces in China, which was part of the Eight-Nation Alliance. During the Chinese uprising against foreign influence, he fought to put down the Boxer Rebellion between 1899 to 1901. Between 1904 and 1908, Lettow-Vorbeck took part in the Herero Wars, which was a series of colonial wars between the German Empire and the Herero people in German Southwest Africa, in present-day Namibia.1

In January of 1914, Lettow-Vorbeck arrived in Dar-es-Salaam, a port city in one of Germany’s colonies on the African continent, called German East Africa, now present-day Tanzania. Lettow-Vorbeck was promoted to the rank of General of the Infantry, equivalent to a Major General in the U.S. military army. He was tasked to protect the colony from external and internal threats.

Lettow-Vorbeck took charge of the colonial defense called the Schutztruppe, or protection force troopers in English. This army was primarily composed of the Askari and a handful of German officers, making the German East African Schutztruppe the first racially integrated army in modern history. “Here in Africa we are all equal, the better man will always outwit the inferior and the color of his skin does not matter,” Lettow-Vorbeck famously said when asked about his army after the war.2 It was a small force, but sufficient for peace enforcement and security purposes since part of the Berlin Conference was the agreement that the colonies will remain neutral towards each other during European wars.3

When Lettow-Vorbeck assumed command, the Schutztruppe was hopelessly behind modern military units—using outdated line tactics in battle and equipment, with rifles of 1871 models while also using smoky powder cartridges. Later, after enlisting the help of a police sergeant major, he managed to modernize the Schutztruppe to the best that their resources allowed. Then, in August of the same year, the powder keg in Europe was ignited in the aftermath of the assassination of the Archduke Ferdinand of Austria. After receiving a letter from the German Kaiser Wilhelm II, Lettow-Vorbeck was ordered to fully mobilize his forces. Lettow-Vorbeck started to prepare for war with the limited troops and supplies he had at his disposal. He decided to try to divert as many resources of his enemies to himself rather than turn them over to the empire and Kaiser. His forces when counting the Schutztruppe, police forces, marines from the SMS Konigsberg, a light cruiser stationed at the colony, and non-combatants added to 14,000 personnel. 4

Lettow-Vorbeck and the colonial governor, Dr. Heinrich Schnee, constantly clashed on how they would use their military force in the upcoming war on their colony’s horizon. Schnee wished to be defensive and only put the Schutztruppe where they were needed. In contrast, Lettow-Vorbeck wanted to attack the neighboring colonies using his small force for employing raids and guerrilla tactics.5

Soon reports came that two English light cruisers, the HMS Astraea and the Pegasus, were firing at a wireless tower near the shore of the colony.6 After receiving these reports, Lettow-Vorbeck disobeyed the governor’s orders, and sent troops into British East Africa and attacked the critical Uganda Railway and other military targets.

By November and after nearly two months of small-scale engagements and skirmish on the borders, Lettow-Vorbeck received word that Expeditionary Force B, an assault force consisting of British African and Indian troops, were on converted ocean liners, and slowly steaming towards Tanga. The reason for the slow pace was that the transports were only capable of seven knots while being escorted by two light cruisers. At the same time, Expeditionary Force C attacked the Usambara Railway near Mount Kilimanjaro. This was an attempt to end the campaign quickly in order to send to remaining British troops to back Europe. Under short notice, Lettow-Vorbeck sent Major Goerg Kraut to defend the railway.7 At the same time, Lettow-Vorbeck himself took charge of the defense of the city, as his forces were arriving mostly by narrow gauge trains and trucks. The British were unloading troops and equipment and demanded the surrender of the city. A German lieutenant ended up tricking the British under the belief that he was receiving the terms of their surrender from his superiors and that the bay had been heavily mined. This allowed Lettow-Vorbeck’s forces a few days for preparation. With that, Lettow-Vorbeck managed to muster a force of a thousand troops to defend against a total force of 8000 British Indian and African expeditionary troops.8

The Battle of Tanga started at midnight on November 2, 1914. The British were confident in a victory due to their overwhelming superiority and believing that they would seize the city by daybreak. Force B arrogantly committed themselves to a full-frontal assault, divided into two forces, and pushed to the city. The northern assault force consisted of Indian troops and pushed through mostly farmland being largely successful. They managed to reach the city center and pulled far ahead to the southern assault force. The southern assault force had to fight through woodlands as well as encounter fierce resistance and counterattacks. This caused the southern assault force to retreat, in fear of being outflanked and surrounded. The northern assault force had to fall back in order to protect their retreating allies. By November 5, the British forces made a full retreat.9

A nickname of the Battle of Tanga is the Battle of Bees because, during the assault, the British disturbed several beehives, which did not affect the assault in any significant way, but it surely did not help.10 Initially, there was a joke that the bees were fighting for the German side of the conflict. However, the bees started to attack the Germans as they chased the retreating British forces. During the hasty retreat, the attacking forces left equipment and supplies such as modern weapons, ammunition, and food, which was later distributed among the German forces. The Askari took it as a great honor and respect as the received the new equipment from their superiors.11

The first significant engagement of the East African Campaign was a German victory and a British defeat with the number of casualties at nearly a thousand troops. One brigade lost half of its officers. The battle is considered in British history as one of their greatest military failures. The Kaiser himself noted that “the brilliant victory at Tanga has pleased me [Kaiser Wilhelm] greatly.”12 Lettow-Vorbeck’s forces received relatively light casualties compared to the British with only 147 troops being killed or wounded. Those numbers are misleading because in terms of percentages, the Germans had a casualty rate of 14.7% of their defending force, and the British had 12.4% of the attacking force. And this was a common theme throughout the campaign.

A few months later, after another victory at the Battle of Jasini, Lettow-Vorbeck realized that the forces could not continue fighting in large-scale open combat with the British. So, he went back to his guerrilla tactics, using the advantage that his forces’ small size gave him. He often used his forces to outflank the enemy and disrupted supplies lines. Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck continued to fight till November 25, 1918, two weeks after the end of the war. He returned to Germany as a war hero, known as the last German General, to surrender.

- “Paul Emil Von Lettow-Vorbeck: German Army Officer (1870-1964) – Biography and Life,” (PeoplePill. Accessed February 26, 2020. https://peoplepill.com/people/paul-von-lettow-vorbeck/. ↵

- Robert Gaudi, African Kaiser: Paul Von Lettow-Vorbeck and the Great War in Africa, 1914-1918 (Place of publication not identified: C HURST & CO PUB LTD, 2017), 2. ↵

- Paul Emil, MY REMINISCENCES OF EAST AFRICA: the German East Africa Campaign in World War One – a Generals… Memoir. (S.l.: LULU COM, 2019), 7. ↵

- Paul Emil, My Reminiscences of East Africa: the German East Africa Campaign in World War One – a Generals… Memoir (S.l.: LULU COM, 2019), 17. ↵

- Robert Gaudi, African Kaiser: Paul Von Lettow-Vorbeck and the Great War in Africa, 1914-1918 (Place of publication not identified: C HURST & CO PUB LTD, 2017),182. ↵

- Paul Emil, My Reminiscences of East Africa: the German East Africa Campaign in World War One – a Generals… Memoir (S.l.: LULU COM, 2019), 21. ↵

- Robert Gaudi, African Kaiser: Paul Von Lettow-Vorbeck and the Great War in Africa, 1914-1918 (Place of publication not identified: C HURST & CO PUB LTD, 2017), 176. ↵

- Paul Emil, My Reminiscences of East Africa: the German East Africa Campaign in World War One – a Generals… Memoir (S.l.: LULU COM, 2019), 33. ↵

- Robert Gaudi, African Kaiser: Paul Von Lettow-Vorbeck and the Great War in Africa, 1914-1918 (Place of publication not identified: C HURST & CO PUB LTD, 2017), 201. ↵

- Robert Gaudi, African Kaiser: Paul Von Lettow-Vorbeck and the Great War in Africa, 1914-1918 (Place of publication not identified: C HURST & CO PUB LTD, 2017), 198. ↵

- Robert Gaudi, African Kaiser: Paul Von Lettow-Vorbeck and the Great War in Africa, 1914-1918 (Place of publication not identified: C HURST & CO PUB LTD, 2017), 198. ↵

- Byron Farwell, The Great War in Africa: 1914-1918 (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1989), 179. ↵

27 comments

Trenton Boudreaux

World War I’s impact on the great power’s colonial holdings is not often talked about so I never heard of this German war hero. I am pleasantly surprised at his racial attitudes being more liberal for the time. It’s interesting how the Germans, who so often during WW1 and WW2 are depicted as villains, actually had a racially mixed army decades before the US.

Ian Mcewen

most interest in wars of the colonel period was focused on Europe and the USA, but wars between the powers of this time was all around the world. Africa, India, Caribbean, china, and the Indonesian islands, were places that were drawn into these conflicts and the natives were often subjected to mistreatment from their European overseers or companies that were sponsored by European powers.

Grace Frey

Seth, thank you for writing this article; the effects of World War I affected the colonies in ways that are often not recognized or talked about in the way that other major WWI events are. I was not aware of this aspect of the war or the depth of the involvement of the colonial army: the Askari. Like many others in the comments have noted, it is nice to hear about a story involving colonies being treated with respect and dignity. However, the fact that they were still colonized takes away from that a little.

Santos Mencio

It’s always good to hear a story from the perspective outside of the norm, the German empire gets quite a bad rap when they were really just like every other participant in the first world war. I’d never heard of Lettow-Vorbeck until I read this article, and the comparison between him and Lawrence of Arabia is fascinating to me and it makes me want to look deeper into both of their careers.

Raul Colunga

Much of what is talked about during the time of Africa’s colonialization is negative because of the how poorly it effected the current countries if Africa. However, Der Lowe’s progressiveness and treating the natives as equal was a breath of fresh air. It is a shame that more people did not have the same views that Der Lowe did instead of simply exploiting the Africans and their resources.

Maya Simon

Tanga’s Strategic Significance to the Germans and the British Defeat. Tanga was strategically important as German East Africa’s most important sea port and the connection to the Usambara railway. Aitken’s advance on Tanga began on 4 November 1914 after his troops had landed three kilometers south of the town. Paul Emil von Lettow-Vorbeck, also called the Lion of Africa, was a general in the Imperial German Army and the commander of its forces in the German East Africa campaign.

Jourdan Carrera

The first word war is extremely interesting to me as it lead to the death of multiple proud and noble empires which had existed for hundreds of years to only have a war to undue their centuries of existence and conquest. The author does an excellent job in detailing the background of the war and how it lead to the Germans holding out in Africa despite being cutoff from home.

Yazmin Garcia

When reflecting on previous world history courses that I have taken I can’t seem to remember a time when World War I was involved anywhere within Africa. So this article was quite refreshing to read up on. I think the methods of attack are quite unique and resourceful considering the Germans tricked the British long enough to wait for thousands of troops to come and how the British planned on using Bees.

Andres Ruiz

The East African campaign was an utter mystery to me prior to reading this article, and seeing as how I find the history of military strategy interesting, this is quite the surprise, considering the importance of integration. The attacks from bees are historically hilarious, and I believe that this story of brave bee soldiers defending their home from 2 foreign armies deserves recognition at worst, and at best a medal

Nathaniel Bielawski

Before reading this article, I had no idea that World War 1 had any conflicts outside of Europe. I find it impressive how, under Lettow-Vorbeck, the Schutztruppe was able to fight off British attackers with such outdated technology. No wonder they were delighted to receive newer armaments and food supplies! I also find it funny how the battle became known as the Battle of the Bees. I guess soldiers have humor after all!