Winner of the Spring 2017 StMU History Media Awards for

Best Article in the Category of “Culture”

When entering a Mexican restaurant today, one takes notice of the different aromas, both sweet and savory; one notices the patrons often speaking their language of Spanish; one hears the vibrant tunes of a jukebox; however, one might ask whether the art hanging on the walls of the restaurant isn’t also worthy of the patrons’ attention? One may have seen the famous work of art depicting a woman of colored skin, brown as sugar, contrasting with the white of beautiful calla lilies; or, if not, one might at least be familiar with another work by that same painter.1 The name of this artist, who is known far beyond the Mexican restaurants that hang his famous paintings and murals, is Diego Rivera.

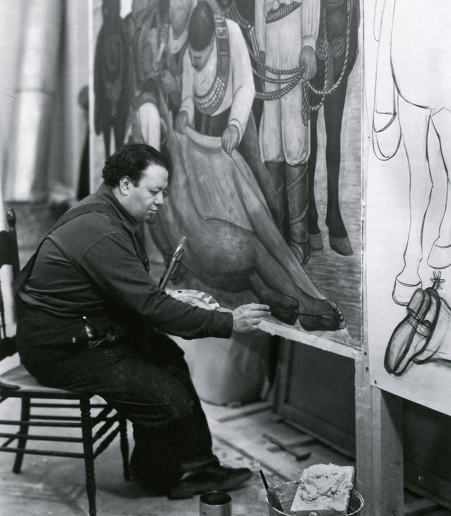

Born in Guanajuato, Mexico, on December 8, 1886, Rivera grew up always seeming to have a hand for creating art. As a child, he had his own studio to work in and later he was granted a scholarship that allowed him to take his talent to Europe, especially to France, where he spent ten years expanding and perfecting his techniques. He is best known for his many influential murals and paintings that illustrate the struggles and lifestyles of the Mexican working class. Among his most famous murals is The History of Mexico from the Conquest to 1930, housed in the National Palace in Mexico City; The Making of a Fresco in San Francisco; and Detroit Industry, located in the city that was home to the American industrial worker in the early twentieth century.2

In the autumn of 1922, Rivera joined the Mexican Communist Party. This organization positively impacted the Mexican community through supporting miners’, factory workers’, and farmers’ rights. With the support of those miners, factory workers, and farmers, Rivera formed the Union of Technical Workers, Painters, and Sculptors. Through the Union, Rivera opened free art schools all over Mexico, through which he was able to spark the Mexican mural movement, enabling his protégés to showcase their art, inspired by Rivera’s own murals. Rivera became well-known in Mexico, and even people from different countries came to his Union to participate.3

In 1929, Rivera began working on a series of frescoes titled History of Mexico from the Conquest to 1930. The art piece took twenty years to complete because of minor adjustments and additions, and he also worked on other pieces in the interim. However, during this time of his busiest artistic activity, he was expelled from the Mexican Communist Party for being “too busy” painting. Despite his expulsion, he continued to favor the working class and always believed he was one of them.4 On February 9, 1934, Nelson Rockefeller was said to have sent workers to destroy a mural located in the Rockefeller Center in New York City, a mural Rivera had spent many weeks painting with smooth precision. The painting was destroyed because of a portrait of Vladimir Lenin painted in the mural, which was not originally in the sketch sent for Rockefeller’s approval. This left Rivera in a state of depression and exhaustion after realizing his hard work was put to waste, without even being given a chance to be named.

Despite the controversies Rivera encountered throughout his career he was still a magnificent painter and influenced much of Mexico’s national art.5 In 1947, another one of Rivera’s murals heated his audience, Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in the Alameda. It was located in the Hotel del Prado across the street from Alameda and the painting covered the history of the park and its peoples (from Rivera’s perspective) all the way from the years of the Spanish Inquisition to the Mexican Revolution. The reason it sparked criticism and caused demonstrators to slash the fresco was because the words “God does not exist” were written in the mural. Rivera, of course, repaired the damages made. In 1956, a year before his death, he announced “I am a Catholic,” and changed the wording on the fresco.6 It was among one of the last great murals he painted. But despite the controversies that Rivera encountered throughout his career, he was still a magnificent painter and influenced much of Mexico’s national art.7

In addition to being a hard worker and a talented painter, Rivera was also great with the ladies. While in Paris he first became engaged to a Russian artist named Angelina Beloff, with whom he had a son, Diego Jr., who unfortunately died at fourteen months from the influenza epidemic of 1919-1920.8 In 1921, he returned to Mexico, where he met a fine beauty from Guadalajara named Lupe Marin. Just a short year later they were married, leaving Angelina in Paris still believing that they were engaged. In the years that followed, Marin bore Diego two daughters, Guadalupe and Ruth.9 However, his infidelity caused their marriage to fall apart, with Marin left raising their daughters on her own. By 1929, Rivera had already remarried, but this time to the famous Frida Kahlo.10

Rivera was working on a painting in the National Palace in Mexico City when Frida approached him; she requested that he get down from the scaffold and give his honest opinion on her own work. After looking at her work, he called it “an unusual energy of expression,” calling her an authentic artist. She invited him to see more of her work at her home in Coyoacán. From there, a friendship blossomed, and soon they fell in love.11 Their marriage was not like any ordinary marriage; it was an emotional roller coaster of a relationship that was well depicted in both of their works, especially in Kahlo’s. She accompanied him everywhere: San Francisco, New York, Detroit, and many other places. They managed for many years, up until Rivera became involved with Frida’s younger sister. They then divorced in 1940.

During this time, Leon Trotsky (Soviet politician) was a target for many agents of Joseph Stalin and was found in his home with a pickaxe jabbed in his head.12 Previously, Rivera and Frida’s home in Coyoacán served as an asylum for Trotsky and his wife as a refuge from these assassins of Stalin’s. While in their home Casa Azul, Kahlo and Trotsky had an amorous affair, and a subsequent quarrel between him and Rivera.13 Rivera cut off any interaction with Trotsky and fled to San Francisco, where he started working on a mural. The police questioned Kahlo about Trotsky’s death, and she later followed Rivera to San Francisco. They remarried that same year, and despite his infidelities, they continued to be passionately in love. However, in 1954, after fourteen more mercurial years of marriage, Kahlo died, and Rivera mourned her death for a year before marrying his third wife, Emma Hurtado. Diego Rivera had a way with women, and his big belly and smelly self did not get in the way of his passion for both art and women.

Rivera was heavily involved in politics at an early stage of his life and continued to be up until his death. In 1955, he was diagnosed with cancer and traveled all the way from Mexico to Moscow to get treatment. Two years later, on November 24th, he passed away in his home in San Angel, Mexico City, Mexico. He wanted his ashes to be spread alongside those of Frida Kahlo in a templo he built; instead, he was buried. Rivera was head of the Anti-Imperialist League and held memberships in the National Peasant League and the Workers’ and Peasants’ Bloc. Also, he rededicated himself to the Mexican Communist Party in 1926 and was a delegate to the Moscow Peasant Congress in 1936.14 Rivera in many ways resembled the indigenous people of the working class illustrated in his works of art. Not only did they share the same native country, but they too were concerned for the political movement and the aftermath of the Mexican Revolution, and they too had the passion and drive to continue working hard, in both sickness and in health.

- Diego Rivera, “Desnudo con Alcatraces,” painting in oil, 1944, original in Private Collection. ↵

- Susan Goldman Rubin, Diego Rivera: An Artist for the People (New York: Abrams Books for Young Readers, 2013), 6. ↵

- Susan Goldman Rubin, Diego Rivera: An Artist for the People (New York: Abrams Books for Young Readers, 2013), 16. ↵

- Susan Goldman Rubin, Diego Rivera: An Artist for the People (New York: Abrams Books for Young Readers, 2013), 22. ↵

- Susan Goldman Rubin, Diego Rivera: An Artist for the People (New York: Abrams Books for Young Readers, 2013), 26. ↵

- William Stockton, “Rivera Mural in Mexico Awaits it New Shelter,” New York Times, January 4, 1987. Accessed April 17, 2017. http://www.nytimes.com/1987/01/04/arts/rivera-mural-in-mexico-awaits-its-new-shelter.html. ↵

- Susan Goldman Rubin, Diego Rivera: An Artist for the People (New York: Abrams Books for Young Readers, 2013), 26. ↵

- Susan Goldman Rubin, Diego Rivera: An Artist for the People (New York: Abrams Books for Young Readers, 2013), 12-13. ↵

- Susan Goldman Rubin, Diego Rivera: An Artist for the People (New York: Abrams Books for Young Readers, 2013), 16-18. ↵

- Frida Kahlo was an iconic revolutionary Mexican artist widely recognized for her disturbing personal self-portraits of the female body and known for her Tehuana style. See Encyclopedia of Activism and Social Justice, 2007, s.v. “Kahlo, Frida (1907–1954),” by Gary L. Anderson and Kathryn G. Herr. ↵

- Susan Goldman Rubin, Diego Rivera: An Artist for the People (New York: Abrams Books for Young Readers, 2013), 18-21. ↵

- Encyclopedia of Activism and Social Justice, 2007, s.v. “Trotsky, Leon (1879–1940),” by Gary L. Anderson and Kathryn G. Herr. ↵

- Encyclopedia of Sex and Gender, 2007, s.v. “Kahlo, Frida (1907–1954),” by Fedwa Malti-Douglas. ↵

- Encyclopedia of Activism and Social Justice, 2007, s.v. “Rivera, Diego (1886–1957),” by Gary L. Anderson and Kathryn G. Herr. ↵

127 comments

Kanum Parker

I never thought much of the paintings in the restaurant and now I understand them a little more. This article cleared my mind on these paintings and what they may represent. As for Rivera he was a great painter and did many paintings for famous people I didn’t a Mexican artist painted for. He surely helped the people realize the Mexicans have talent as well.

Andrea Ramirez

I was very engaged through the whole article because of the way you explained. I did not know that Diego went to France to learn painting, which was an excellent opportunity that contributed positively to his development as a painter.

Rivera was definitely a hard worker and a talented painter. Likewise, I admired how Rivera made a great effort to make art accessible to those who liked it but, perhaps, could not afford classes or a painting school.

Finally, I really liked that in your article you included many of the paintings that Diego Rivera made, because it allowed me to admire more of his art that I did not know. You really did a good job selecting them.

Adam Alviar

I had no real prior knowledge of art before this article, or the history behind art. This article did a great job highlighting Diego Rivera’s actions of creating art, and the way he brought it to life. He really seemed to have poured every ounce of himself into all of his artworks and he takes them very seriously, and passionately. It was unfortunate he kept going through women without knowing what he was really looking for.

Justine Ruiz

I was in complete shock to discover that this was the Rivera who married Frida. Throughout the entire time I was reading this article, I never pieced it together. This article did a great job in explaining who Rivera was and how exactly his art came about. He was truly a wonderful artist who made artwork for protests about the working rights of Mexican community. He wasn’t your typical artist, he incorporated politics, racial, and ideologies into each piece of artwork he did. Rivera truly took pride in his work. I enjoyed reading this!

Daniel Gimena

It is always passionating to read about something or someone famous that you didn’t know about.

Before reading this article, I had never heard about Diego Rivera, but now I realize how important he must have been for art history in the 18th and 19th century, specially in Mexico. I am pretty sure that I must have seen one of his painting hanging in a restaurant or bar without knowing who was the author.

I liked the way the author wrote the article. He made me want to finish the article because in every different paragraph he introduces something new about Diego Rivera.

What impressed me the most, has been the fact that Diego Rivera had been married with Frida Kahlo. It impressed me because I have heard a lot about Frida Kahlo but never about Diego Rivera.

Antonio Holverstott

Diego Rivera used his artwork to protest for the working rights of the Mexican community instead of the written word or through demonstrations. He used his membership within a Communist party to advance his labor advocacy which he expressed through his artistic works. These activities place him under the glance of racially and ideologically prejudiced people, especially during the Red Scare in the 1950s.

Berenice Alvarado

I loved this article. Not only because it talks about the life of a famous Mexican artist but because it gives facts about how his art came to life. I don’t know much about Rivera, however, when I took AP Drawing in high-school my teacher would talk about him and Frida Kahlo. And the art they both created in fact is really known in Mexico. And I thank them for making art so much fun and alive. Also this article was really fun to read because I didn’t know that one of his murals was destroyed.

Samuel Vega

This article was a glimpse of both art and politics. The images in the article give you a sense of Rivera’s talent. The selected images brought the article to life. You can see how the murals told the history of Rivera’s people. I hope I am more of aware of art when I see it displayed in restaurants or buildings and be curious of what the story is behind the artist.

Jose Chaman

This article is really interesting. The way in which it is written allows a fluid and entertaining reading. I have learned thanks to this work that Diego Rivera was the husband of Frida Khalo, in addition to the incredible contribution he had towards Mexican culture. His talent is truly indisputable, and thanks to the images of his paintings provided in this article, we can confirm the excellence of Diego Rivera’s gift

Alexander Avina

I really enjoyed reading this article about Diego Rivera, who was a very talented artist. The article was very well-written and was able to paint a picture (no pun intended) of Rivera’s life and artistic career. Before reading this, I only knew of Rivera from learning about Frida Kahlo. I did not know that he was also a very talented artist. As a reader, I could clearly see why this article won an award. The flow of the article was very smooth and easy to read.