Sleep is one of our most basic and essential physiological needs for our existence and proper functioning. In fact, this is equivalent to a third of our lives, that is, 25 to 30 years of our lives is spent in sleep. However, sleep is an aspect of our lives that, until recently, had been under-appreciated. Recent studies reveal the negative effects of sleep deprivation and, conversely, the benefits of getting quality sleep.

Dr. Matthew Walker has made a wonderful contribution to the study of sleep, demonstrating through his research the importance of sleep and the effects that it has on the immune system, the cardiovascular system, the endocrine system, and on our cognitive capacity, and on the regulation of our emotions. As he said, “There does not seem to be any major organ within the body or any brain process that is not enhanced by sleep and is not impaired when we do not get enough sleep.”1 Likewise, Shawn Stevenson has stated that in general, “being awake is a catabolic state (breaks you down) and being asleep is an anabolic state (rebuilds you).”2 Therefore, in this article I will discuss the corrosive effects that sleep deprivation has, specifically, on our ability to learn.

Let’s begin by defining what sleep is. Sleep is a period of rest during which the body recovers the vitality depleted by the physical and mental activities during the preceding period of awakeness and during which the various tissues regain their normal state by the elimination of waste products and the building of new tissue.3 In fact, all species studied to date sleep.4 This includes insects such as bees and flies, as well as small and large fish. Likewise, the reptiles, the amphibians, the mammals, and every specie of bird, sleep. Finally, even invertebrates, like molluscs and worms, and, of course, human beings, sleep.5 However, unlike the rest of the animal kingdom, human beings are the only ones who, by our own will, deprive ourselves of sleep. But it is essential to know that this deprivation leads to terrible consequences.

Many brain functions are restored by, and depend on, sleep. It is when we sleep that our ability to concentrate and make reasonable choices is restored and improved. Furthermore, our memory and our ability to absorb new information also get this benefit.6

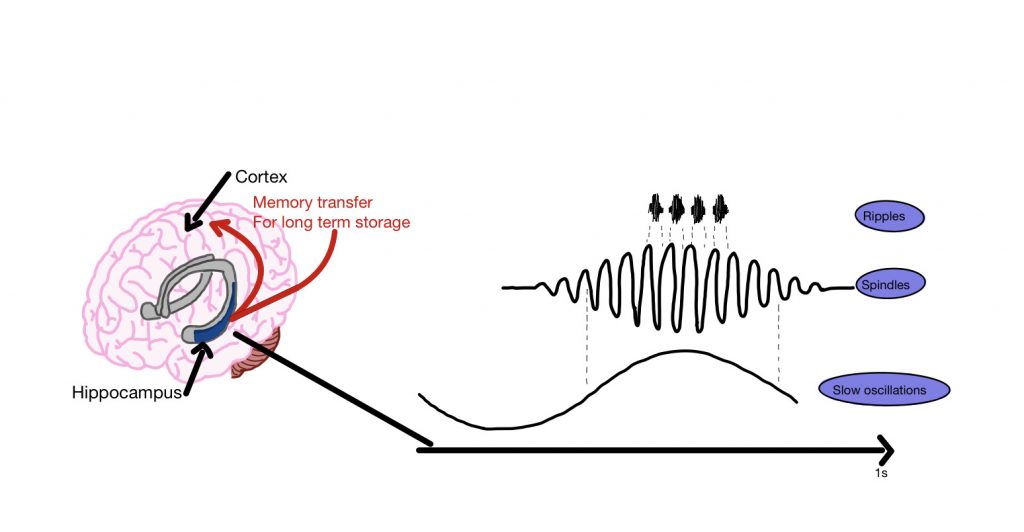

Every day, we find ourselves constantly absorbing information and learning new things, consciously or unconsciously. When we talk about obtaining information based on data, such as remembering someone’s name, which is episodic memory, it is a region of our brain called the hippocampus that is responsible for storing this information in the short term. The problem is that the hippocampus has limited storage capacity. Therefore, sleeping the night before learning has many benefits. This is when an electrical transaction occurs where memories and experiences pass from temporary storage (hippocampus) to a long-term and durable one, called the cortex, which is another region of the brain. Thus, the irrelevant information is eliminated, and our hippocampus is prepared for the next day to continue learning new things. But, what happens if we do not allow this natural process to occur? Well, as we will see later, being sleep deprived gives a great disadvantage to our learning. First of all, the little information that we can learn or retain in this state will be fragile and will be forgotten at great speed. Second, there will be a point where we cannot add more information or where we can overlap one memory with another, something called “forgetting by interference.” Dr. Walker performed an incredible experiment to prove this. To do this, he took a group of young individuals who were separated into two groups at random. At noon, both groups underwent an intense learning session (one hundred faces with their names) and both groups demonstrated comparable performances. Nevertheless, after the test, one of the groups was allowed to take a 90-minute nap there in the sleep lab. Meanwhile, the rest of the participants had to stay awake, also in the lab. All of the individuals had electrodes attached to their heads to measure their sleep. Later that same day at six o’clock, the two groups went through another round of rigorous learning (over a hundred other faces with their names). What the researchers wanted to know with this test was whether our learning ability declines as we stay awake and, if the answer was positive, whether sleep can reverse the saturation effect and restore learning ability. The results were as follows: First, the learning capacity of the group that had to stay awake declined. Meanwhile, those who took a nap completed the exercise much better. Second, those who had slept had a 20% learning advantage compared to the group that did not take a nap, proving that sleep restores the brain’s ability to learn by making room again for new memories.7 “By analyzing bursts of activity of the sleep spindle, we observed a surprisingly reliable circuit of electrical current pulsating throughout the brain, repeating itself every one hundred to two hundred milliseconds. The pulses weaved a back and forth path between the hippocampus, with its limited short-term storage space, and the much larger long-term storage site in the cortex.”8

Thus, as we can see, sleeping before learning is very beneficial by refreshing our ability to create new memories. Now, sleeping the night after learning is equally essential because, while we are sleeping, our brain is consolidating our memories. In other words, sleep provides a kind of resistance to our memories against forgetting. Consolidation basically refers to ”the processing of memory traces during which the traces may be reactivated, analyzed and gradually incorporated into long-term memory.”9

Some time ago, a study conducted by researchers John Jenkins and Karl Dallenbach showed us this. For their study, they recruited individuals and had them learn a list of non-sense syllables. Thus, the researchers measured the speed at which the participants forgot those memories in different time intervals (1hr, 2hr, 4hr, and 8hr) either by staying awake or by sleeping. Therefore, in total there were eight groups of participants (two for each interval, since one could sleep and the other could not). The results were clear: the time spent sleeping contributed to building the new information acquired. Instead, time spent on vigilance resulted in a rapid trajectory of forgetting newly acquired information.10 “The constancy of the experimental conditions… was greater after intervals of sleep than after intervals of waking.”11 These types of experimental results have been demonstrated in numerous investigations, showing that “sleep provides a 20% to 40% memory retention benefit, compared to the same amount of time spent awake.”12 It may or may not be relevant, but imagine how it can benefit or harm students and their grades.

Therefore, the anatomical dialogue established among the hippocampus and the cerebral cortex is harmonic: “By transferring the memories of the previous day from the short-term store of the hippocampus to their long-term home within the cerebral cortex, the individual wakes up with those memories already safely archived and having regained his short-term storage capacity for new learning.”13

So, sleeping gives us the benefit of consolidating our memories by moving the previous day’s experiences to a more permanent safe place and thus waking up with a renewed ability to learn. But, if we deprive ourselves of this natural gift, we do not allow this process to occur and, accordingly, it will be more difficult for us to retain information and remember it.

Now, another of the most reliable negative effects of sleep deprivation that affects our learning, is the degradation of attention. Dr. David Dinges has done quite a few studies regarding the effects of sleep deprivation, but, in one particular study, he showed us this. To do this, they conducted a very well-controlled experiment where some participants were chronically sleep restricted, while others were totally sleep deprived. The sleep restriction experiment lasted 14 days, and participants were divided into three groups with different sleep “doses.” The first group was allowed to sleep only four hours a night, the second group was allowed to sleep six hours a night, and the third and luckiest group, was allowed to sleep eight hours. In the total sleep deprivation experiment, the subjects stayed awake for 88 hours. Now, the participants, with their doses of sleep, were given an attention test to measure their concentration, where the participants had to press a button in response to a light that appeared on the screen. The light appeared unpredictably, sometimes consecutively, sometimes with slight pauses, for ten minutes. Thus, both the response and the reaction time of the subjects could be measured. The results were as follows: People who slept eight hours each night maintained stable, near-flawless performance for all 14 days. The group totally deprived of sleep for all three nights suffered a terrible deterioration. After the first sleepless night, their failed responses increased by 400%, and these deficiencies amounted to the same extent after the second and third nights of no sleep. As for the group that slept four hours, after six nights on this poor sleep diet, their execution was just as bad as that of those who had not slept for 24 continuous hours. The participants’ performance worsened even more after eleven days of sleeping four hours, equaling that of someone who accumulated 48 hours without sleep.

Finally, and in my opinion, most surprising, the group that slept six hours a night, after only ten days maintaining this amount of sleep, had their performance as affected as if they had gone 24 hours straight without sleep. “Since chronic restriction of sleep to 6 h or less per night produced cognitive performance deficits equivalent to up to 2 nights of total sleep deprivation, it appears that even relatively moderate sleep restriction can severely impair waking neurobehavioral functions in healthy adults.”14 These are really profound revelations, because if we analyze it, many people in their daily lives maintain this rhythm of sleep without being aware of the damage they are causing.

Now, though, many students can identify with this sleep rhythm, sleeping less than seven hours a night and, in many cases, completely depriving themselves of it. One of the main reasons students deprive themselves of sleep is to study for an exam. But is that really a good idea? Dr. Walker did an experiment to give us an answer to this. For it, he recruited several people and divided them into two groups, one for sleep and one for sleep deprivation. Thus, both remained awake throughout the day, and at night one group slept while the other remained awake under surveillance in the laboratory. The next day, all the participants were fitted with an MRI (Magnetic resonance imaging) scanner and tried to learn the facts contained in a list while taking snapshots of their brain activity. Afterwards, they waited for both groups to sleep for two nights, and then gave them a test to see how effective their learning had been. The procedure (waiting two nights later) was done in this way to ensure that, “the deficiencies observed in the sleep-deprived group did not respond to the fact that they were too sleepy…Therefore, the manipulation of sleep deprivation only had an effect during the act of learning, and not during the later act of remembering what was learned.”15 What they discovered was that there was a 40% deficit in the ability to enter new data into the brain of the sleep-deprived group, compared to the group that had slept through the night.

To understand what was happening in the brain to produce this deficit, they reviewed the brain activity of both groups during the learning process and compared them, focusing on the hippocampus, “the brain’s inbox, where new information is received.”16 Participants who had slept that night had a lot of healthy activity in the hippocampus related to learning. In contrast, in the awake group, no significant learning activity was observed at all. “It was as if sleep deprivation had shut down their internal memory and any new incoming information just bounced back.”17

In addition, that little information that we can learn while deprived of sleep, “is forgotten faster in the following hours and days. Memories formed without sleep are weaker memories that quickly evaporate.”18 Sleep deprivation affects the DNA and learning-related genes of brain cells in the hippocampus. “Cellular and molecular processes in the hippocampus critical for memory consolidation are affected by the amount and quality of sleep obtained.”19 Thus sleep deprivation, “weakens the memory-making apparatus within the brain, preventing the construction of lasting memory traces.”20

Lastly, by not sleeping the first night after learning, our memories cannot be consolidated. Dr. Robert Stickgold did an amazing study that showed us this. To do this, he took 133 subjects and had them learn a visual memory task through repetition. Participants were trained in a single session and then they were tested in a second and equal test, ranging from three hours after the training to seven days. Unlike the other groups, one group was totally sleep deprived the night after training but was subsequently allowed unlimited sleep for two nights before retesting them. So, to determine how much the subjects had retained, they returned to the laboratory to be tested. Some did it the next day after a full night’s sleep, others after two full nights’ sleep, and so on. The results were the following: No significant improvements were observed when tests were performed on the same day as the training session, while tests performed the day after the training showed highly significant improvement. After a full night’s sleep, their newly acquired memories were consolidated and, thus, stronger. Better yet, the more nights slept before the test, the better was their memory retention. “Subjects tested 2 to 7 days after training showed significantly greater improvement than those tested after only 1 day.”21 But, unfortunately, those who were totally deprived of sleep after training and, given two nights of recuperation, did not demonstrate improvements in memory consolidation. “We show that this improvement is absolutely dependent on the first night of sleep, and that subsequent sleep cannot replace the first night requirement. These findings add to related data from the past three decades, which suggest that sleep after training can be important in the consolidation, integration, and maintenance of memories…A single night of sleep deprivation definitively aborted the normal consolidation process of learning.”22 Thus, as Dr. Walker puts it, “If you don’t sleep the first night after learning, you lose the opportunity to consolidate those memories, even if you do get plenty of catch-up sleep afterwards.”23

Since we have analyzed that sleep poverty has a negative effect on our ability to learn and remember, you may be wondering what you can do to improve it. Here are a couple of sleep hygiene practices that will benefit both your quantity and quality of sleep.

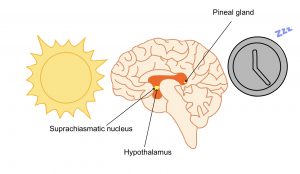

1-Set a wake up and sleep schedule: Each living being has its own internal biological clock called the circadian rhythm, which is located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. This clock monitors our wakefulness and sleep status (among other things). If we get used to going to sleep and getting up at the same time, we will help to synchronize the times of our clock and, therefore, it will be easier for us both to fall asleep at night, and to get up in the morning.

2-Avoid caffeine and nicotine: This is because stimulants will make it difficult to fall asleep. For example, caffeine has a half-life of 5 to 7 hours, and therefore drinking a cup of coffee late in the day can make it difficult and disruptive to sleep.24 Likewise, nicotine, being also a stimulant, has similar effects and often causes smokers to sleep poorly and wake up early due to nicotine withdrawal.

3-Avoid alcohol drinks before bed: Although alcohol produces relaxation in a state of vigilance, it does not lead to a normal and natural sleep: “when ingesting alcohol, the state of the electrical brain waves is not that of natural sleep; rather, it is similar to a light form of anesthesia.”25 Alcohol fragments sleep, causing the individual (although he does not remember it the next morning) to have brief awakenings at night and, therefore, it is not a restful and quality sleep. Alcohol also suppresses REM sleep because, “when the body breaks down alcohol, it produces chemical byproducts called aldehydes and ketones. In particular, aldehydes block the brain’s ability to generate REM sleep…In tests carried out on alcoholics, it has been shown that, when they drink, they hardly present REM sleep.”26

4-Have sunlight exposure during the day: Daylight helps us reset our internal clock. Exposure to sunlight is essential to maintain a regular rhythm of the sleep-wake cycle. The circadian system works like a wind-up clock, to which you have to set the time each day. Thus, the sun is the most important synchronizer that we humans have to mark our internal clock at what time of day we find ourselves.27

5-Make your room dark: Now, in the case of the night, we want to do just the opposite. We want to send the signal to our body that it is already night by keeping our surroundings as dark as possible.

Melatonin, (also called the hormone of darkness), is a hormone synthesized and secreted mainly by the pineal gland that produces drowsiness. But it is only secreted when it is night, and when it is dark. When the sun goes down, along with daylight, it informs our suprachiasmatic nucleus that it is night. And, thanks to its instructions, our pineal gland begins to secrete large amounts of melatonin into the bloodstream, which tells our body that it is time to sleep.28 However, exposure to electric light at night will put an end to that natural order. “Artificial light, even the most moderate, deceives the suprachiasmatic nucleus, making it believe that the sun has not yet set.”29 In consequence, electric light puts a powerful brake on the brain by preventing the secretion of melatonin. Therefore, keeping our surroundings dark is essential to improve our sleep.

6-Avoid using electronic devices at least 30 minutes before bed: This is related to the two previous points; light is a suppressant for melatonin. But, the blue light emitted by our electronic devices (TV, iPad, phone, etc.) has a greater impact on suppressing melatonin release than yellow light, even when the intensities are equivalent.30 The more time we spend in front of an electronic device at night, the greater the delay in the release of melatonin, which will make it difficult to fall asleep. In turn, this can interfere with our circadian rhythm. For that reason, try to stop using electronic devices at least 30 minutes before going to sleep.

7-Cool bedroom: A cold bedroom helps to reach a comfortable body temperature that facilitates a deeper sleep. To fall asleep more easily, your body temperature needs to drop by about one degree Celsius. That is why it is always easier for us to fall asleep in a cold room than in a hot one.

The decrease in body temperature is detected by a class of temperature-sensitive cells located within the hypothalamus. These cells live next to the suprachiasmatic nucleus (our 24-hour biological clock). When our body temperature drops at night, thermosensitive cells send a message to the suprachiasmatic nucleus that, along with the signal that it is getting dark, prompts it to start secreting melatonin, and with it, the command to sleep. “Therefore, nocturnal melatonin levels are controlled not only by the decrease in light at sunset, but also by the decrease in temperature that coincides with sunset.”31

The ideal bedroom temperature for falling asleep is 18.3 C, but this can vary according to each individual and their own physiology, gender, and age.32

8-Avoid eating heavy meals and drinking lots of fluids close to your bedtime: Thus, then, a large dinner can cause indigestion, which can interfere with our sleep. When it’s late at night, opt for a light snack instead. In the case of beverages, drinking a lot of liquids close to our bedtime can cause us to get up frequently to go to the bathroom, which will be interrupting our sleep.

9-Make a night routine: Creating a night routine allows us to be consistent with our bedtime and, in general, with our good hygienic sleep practices.

Sleep deprivation leads to dire consequences in many ways but, as we have explored in this article, our ability to learn is one area that is definitely affected. First, it is when we sleep that our memories are transported from the hippocampus (our short-term memory), to the cerebral cortex (long-term memory). This allows us to remember information by consolidating it and leaving room in the hippocampus to continue learning more things the next day. Second, our attention is impacted by insufficient sleep, making us more susceptible to making mistakes. Also, the little information that we can learn being deprived of sleep is more fragile and is more likely to be forgotten over the days. Finally, by not sleeping the night after learning, we will lose the chance to consolidate what we have learned. Therefore, it is very important that we take care of our sleep, learn sleep hygiene practices, and create better habits.

- Matthew P. Walker, Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams, First Scribner hardcover edition (New York: Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc, 2017), 15. ↵

- Shawn Stevenson and Sara Gottfried, Sleep Smarter: 21 Essential Strategies to Sleep Your Way to A Better Body, Better Health, and Bigger Success, 1st edition (Rodale Books, 2016), 34. ↵

- “What Is Sleep?,” Scientific American 130, no. 2 (1924): 88. ↵

- Giulio Tononi et al., “Enhancing Sleep Slow Waves with Natural Stimuli,” MedicaMundi 54 (January 1, 2010): 82–88. ↵

- Matthew P. Walker, Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams, First Scribner hardcover edition (New York: Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc, 2017), 75. ↵

- Matthew P. Walker, Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams, First Scribner hardcover edition (New York: Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc, 2017), 16. ↵

- Matthew P. Walker, Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams, First Scribner hardcover edition (New York: Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc, 2017), 138-139. ↵

- Matthew P. Walker, Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams, First Scribner hardcover edition (New York: Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc, 2017), 139. ↵

- Gary R Sutherland and Bruce McNaughton, “Memory Trace Reactivation in Hippocampal and Neocortical Neuronal Ensembles,” Current Opinion in Neurobiology 10, no. 2 (2000 April 1): 180. ↵

- John G. Jenkins and Karl M. Dallenbach, “Obliviscence during Sleep and Waking,” The American Journal of Psychology 35, no. 4 (1924): 605–612. ↵

- John G. Jenkins and Karl M. Dallenbach, “Obliviscence during Sleep and Waking,” The American Journal of Psychology 35, no. 4 (1924): 611. ↵

- Matthew P. Walker, Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams, First Scribner hardcover edition (New York: Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc, 2017), 142. ↵

- Matthew P. Walker, Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams, First Scribner hardcover edition (New York: Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc, 2017), 144. ↵

- Hans P. A. Van Dongen et al., “The Cumulative Cost of Additional Wakefulness: Dose-Response Effects on Neurobehavioral Functions and Sleep Physiology from Chronic Sleep Restriction and Total Sleep Deprivation,” Sleep 26, no. 2 (March 15, 2003): 117. ↵

- Matthew P. Walker, Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams, First Scribner hardcover edition (New York: Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc, 2017), 192. ↵

- Matthew P. Walker, Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams, First Scribner hardcover edition (New York: Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc, 2017), 193. ↵

- Matthew P. Walker, Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams, First Scribner hardcover edition (New York: Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc, 2017), 193. ↵

- Matthew P. Walker, Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams, First Scribner hardcover edition (New York: Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc, 2017), 193. ↵

- Toni-Moi Prince and Ted Abel, “The Impact of Sleep Loss on Hippocampal Function,” Learning & Memory 20, no. 10 (October 2013): 558. ↵

- Matthew P. Walker, Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams, First Scribner hardcover edition (New York: Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc, 2017), 194. ↵

- Robert Stickgold, LaTanya James, and J. Allan Hobson, “Visual Discrimination Learning Requires Sleep after Training,” Nature Neuroscience 3, no. 12 (December 2000): 1238. ↵

- Robert Stickgold, LaTanya James, and J. Allan Hobson, “Visual Discrimination Learning Requires Sleep after Training,” Nature Neuroscience 3, no. 12 (December 2000): 1237–1238. ↵

- Matthew P. Walker, Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams, First Scribner hardcover edition (New York: Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc, 2017), 196. ↵

- Matthew P. Walker, Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams, First Scribner hardcover edition (New York: Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc, 2017), 40-41. ↵

- Matthew P. Walker, Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams, First Scribner hardcover edition (New York: Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc, 2017), 330. ↵

- Matthew P. Walker, Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams, First Scribner hardcover edition (New York: Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc, 2017), 330. ↵

- Matthew P. Walker, Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams, First Scribner hardcover edition (New York: Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc, 2017), 28. ↵

- Jolanta B. Zawilska, Debra J. Skene, and Josephine Arendt, “Physiology and Pharmacology of Melatonin in Relation to Biological Rhythms,” Pharmacological Reports: PR 61, no. 3 (June 2009): 383–384. ↵

- Matthew P. Walker, Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams, First Scribner hardcover edition (New York: Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc, 2017), 324-325. ↵

- Matthew P. Walker, Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams, First Scribner hardcover edition (New York: Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc, 2017), 326. ↵

- Matthew P. Walker, Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams, First Scribner hardcover edition (New York: Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc, 2017), 335. ↵

- Matthew P. Walker, Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams, First Scribner hardcover edition (New York: Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc, 2017), 334-337. ↵

23 comments

Victoria Cantu

Great article! I am even convinced that I should start sleeping early after reading this! I’ve always been told that getting a good night’s rest is important but I never knew how crucial it could affect one’s ability to perform in school or how it affects the brain. I loved how you added so much scientific evidence to back up your information. Overall, this was very informative and I believe more students should read about this! I will definitely be sharing this with my peers!

Dylan Damian

Very interesting article to read I never would’ve thought something as simple as sleep could make such an impact on your life. After reading the article it makes sense that sleep could have pros and cons for if you do or don’t get enough sleep, but the difference alone in just getting 6 hours one night and a full 8 hours another is crazy to me. Great article to read

Jacob Adams

I loved this article because sleep is very important to me. I always make sure to get 8 hours of sleep every night so I can wake up fully rested and ready to get work. I actually knew a lot of information about helping someone sleep, I always put my phone away and take a cold shower before sleeping. I think a problem of my generation is a lack of sleep due to the use of electronic devices, however there is a brightness setting on phones now called night mode. It lowers the blue light and makes it easier to look at, which could be helpful for a lot of kids.

Derric Standifer

Before reading this article I didn’t know too much information about sleep deprivation. But now I know without enough sleep and rest, overworked neurons lose their capacity to correctly coordinate information and we lose our ability to retrieve previously learned knowledge. Additionally, it could influence how we perceive what happens. We stop being able to effectively assess the situation, make appropriate plans, and select the appropriate conduct, which results in us losing our capacity to make wise judgments. A decline of judgment occurs. We have a lower chance of doing successfully if we are constantly exhausted to the point of tiredness or exhaustion. Muscles are not properly rested, neurons do not function adequately, and organ systems inside the body are not coordinated. Even accidents or injuries might happen as a result of attentional lapses brought on by lack of sleep.

Emily Rodriguez

I absolutely enjoyed reading this informative article; I learned a lot from it. For one, I was always under the impression that young adults only need six hours of sleep. It seemed like six hours is what I was telling myself was “my goal.” Therefore, I found it very interesting that six hours is still nowhere near the amount of sleep a person should get to avoid sleep deprivation. Another thing I found interesting, was that artificial light is a suppressant for melatonin. I had the idea in my head that if a person takes melatonin, they should be able to fall asleep in any conditions, which I now know isn’t the case. Overall, this article was intriguing, relatable, and informative.

Dejah Garcia

Overall I found it interesting that the Brain only passed the electrical transaction of our memories and knowledge into a temporary stage called the hippocampus. The hippocampus was known to transfer temporary knowledge to the cortex. Once we could transfer this knowledge to the cortex, we would have a “fresh page” to receive more memories and information to our Brain. However, this process was done by sleeping. Understanding and reading the process has helped expand my knowledge of the importance of sleep. ” if you don’t get sleep the first night after learning, you lose the opportunity to consolidate those memories, even if you get plenty of sleep the night afterward.” I definitely will be looking forward to fixing my sleeping schedule in order to improve my concentration in my studies.

Kenneth Cruz

I found this article to be very informative. I remember learning about some of this stuff in General Psychology. Sleep is truly key for keeping a sharp mind. I like how you provided us with experiments that have been conducted to prove that sleep is essential to our learning. Using an electronic device before bed is something we are all guilty of. This is a bad habit especially when preparing for an exam. If you’re up all night looking at social media or watching YouTube, you’re likely to retain that information the next day rather than the material you were trying to retain for your exam. Thank you for this article and for sharing ways to improve our sleep!

Jace Nicolet

I found this very interesting because it connects to my major in exercise science and I can see how the two topics correlate. I catch myself sharing the same habits mentioned that also affect my sleep negatively and it opened my eyes to have a healthier sleeping habit. The author does a great job with keeping my interest throughout the whole article, which I think is caused by me relating to the problems mentioned.

Rafael Portillo

This article not only made me realize the effects sleep deprivation has to the human body and brain but also realize the mistakes and bad habits I’ve formed. As an incoming college freshman, I need to take my sleep seriously in order to be successful in class and in the professional work field. All I learned from this article was so interesting yet scary. You wrote this so clearly and well thought out. Thank you for informing me about this topic.

Madeline Bloom

I always knew that sleep was important for everyday life but I never knew how important it was for school. It was interesting to read about the different studies that was talked about. They tested people sleeping different hours and then tested their abilities to perform tasks and responses to the tasks. I will now be turning my phone off 30 minutes before bed to not stimulate my brain into staying up later.