Judith Sargent Murray was an American woman who argued for women to have roles in society on par with men. During the 1760s, the primary role of women in America was to look after the household. Raising her children, cooking for her family, cleaning the house, and being financially dependent on her husband was the reality for women at the time. Women had little education and virtually no career opportunities available to them. Their schooling was in how to be a good wife and help educate their children to the best of their abilities. Women had to depend on men for financial support. Murray came from a wealthy and supportive family, giving her more opportunities than the average woman, but even if she had access to education, she noticed that her brother had far more advantages than she did in furthering her education.1 Over the course of her life, she championed women’s rights by first writing about expanding women’s roles in society, and then by working to create opportunities for young girls to receive an education, and finally by demonstrating how women could financially support themselves through her own example.

At the age of eighteen, Judith Sargent married a ship captain and adopted two orphaned nieces on her husband’s side and a relative on her side. Her husband, John Stevens, was in a tremendous amount of debt when they married, and when the British government passed the Coercive Act of 1774, put a restriction on goods exporting from the New England, his business suffered. In a panic, Stevens abandoned Judith and ran away, later dying and leaving all of his debts behind for Judith to figure out. In 1775, she began writing to try and support her family through her literary skills. Her first essay was “Desultory Thoughts upon the Utility of Encouraging a Degree of Self-Complacency, Especially in Female Bosoms,” which she had published. Now as a single mother and a widow, Judith was struggling to stay afloat.2

Her passion at that time was to publish writings that showed the importance of letting women have the opportunity to become educated so that they can find employment to support themselves. Judith remarried two years later, in 1788, to Reverend John Murray, one of the founders of the Universalist church in the United States. She moved to Boston with him and her children to found a Universalist congregation. They also went on tours around the country spreading their faith. Judith later gave birth to two children, but only one survived, Julia Maria Murray. With her growing family, Judith knew she could not afford to be constantly traveling, so she stayed in Boston.3 She knew that she needed a form of income, so she continued her writing in an attempt to have her ideas heard. Judith was gaining a small readership, and then important political figures began recognizing her and her work. Her constant struggle with money was the driving force for her adaptability. Coming from a wealthy family and then going to nothing was life-changing for her. Murray knew that if it wasn’t for her husband, she would most certainly have no future doing something she loved. This constant reminder of having to depend on a man was troubling to her. She did not want her children to face that same reality. As a woman in American during the 1790s, she had seen little improvement in the roles women played in society. She saw her writing as a way to get her ideas out to the public so that they might become sympathetic to her critique of disadvantaged women in America.

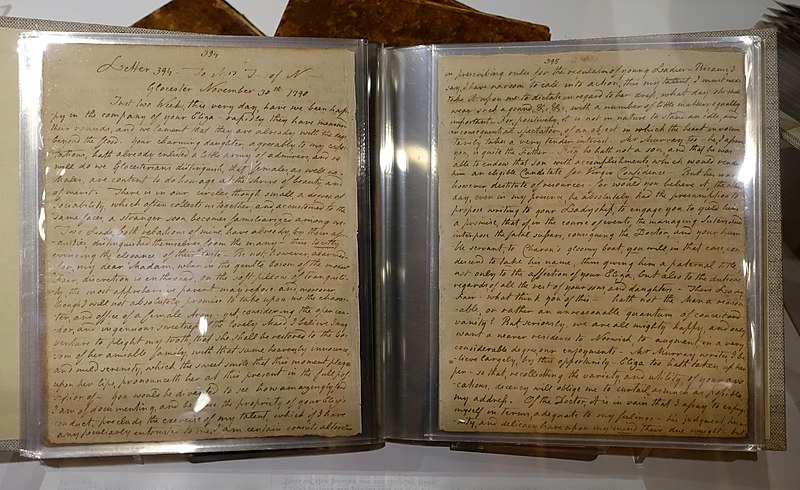

Murray knew that if she continued to write under her own name, she would not get the same attention as she would if she wrote under a man’s name or an alias name. So she did just that. She began writing under multiple pseudonyms: “Honora,” “Martesia,” “Constantia,” or her most famous name, “The Gleaner.” She began writing for the Massachusetts Magazine in 1790. She wrote for their column for two years as “The Gleaner,” writing about how giving women educational opportunities would benefit coming generations. At the same time that her writing was taking off, she was also homeschooling her children until they were old enough to attend an academy so that her children would be able to pursue a future better than her own. She was also teaching family and friends’ children as well. She noticed that her daughters were still disadvantaged when it came to their ability to pursue a higher education, so she decided to write to bring attention to this issue. She also wrote about Universalism and its doctrines on equality. She published a book that included all of her major writings, Selected Writings of Judith Sargent Murray. She urged women to enter a “new era in female history” by overcoming obstacles and taking advantage of the little opportunities they had available.4

One of her famous pieces was titled “On the Equality of the Sexes” in which she writes that women and men may differ physically, but they both are equal when it comes to their spirituality. She explains that if women were entrusted with salvation, then they should also be entrusted with receiving an education. She argued that in the religious world women are encouraged to study the Bible, but yet they are not encouraged to seek an education. This contradiction was the reason she decided to convert from Calvinism to Universalism. She recognized that the Bible seemed to condone male superiority, and she was repulsed by that idea. As her writing took off, she knew that for her to achieve real change in society, she had to become the example of that change.5

Judith wanted to pursue opening a business as a means to become that example, but Thomas Paine wanted her to write for his newspaper, Federal Orrery. But when Murray submitted her column, Paine edited and changed her work completely. This led Murray to decline his offer to work for Federal Orrery, and that ended their relationship. Judith and John were still not bringing in enough money to support their family comfortably, so Judith looked into starting her own business again. Murray published a series of essays in The Gleaner, which significantly contributed to her growing popularity. It was not common for women to have outside work or even own a business. So her being able to achieve both was extremely powerful. She became the first American woman to self-publish a book.6 With her growing wealth, she finally started to feel satisfaction, but women’s roles in society still hadn’t changed. She started a business where people had to subscribe to have access to her past and future works. This business quickly took off and she accumulated over 800 subscribers. She had gained the attention of George Washington, John Adams, Abigail Adams, and many others. Her ideas were finally being heard and being absorbed by the public. While living in Boston, there was a theater performance ban. She decided to attempt some playwriting. In 1792, the ban was lifted and she began writing plays. Due to the Puritan critical views of the theater, Murray struggled to get publicity in the theater world. Unfortunately, her plays did not receive the same recognition as her other writings, and she shifted her attention back to writing about women’s equality.7

With her subscription business’ success, she was financially supporting her family all on her own. This was a huge accomplishment in her life. After struggling for so long to find a stable income, she was accomplishing what seemed impossible for any woman of the time. With her newly gained financial freedom and wealth, Murray was able to open an all-girls academy with her cousins Clementine Beach and Judith Saunders; and they named it The Ladies Academy, opening in 1807. She spent some time teaching students at the academy and anyone who she would run into in her daily life. Her goal of creating opportunities for young girls to be self-sufficient was finally seeming reachable. Her work was used in the Republican Motherhood movement, but her work was used to defend letting women access education to pass down republican values to their children. This was the first step in letting American women have a voice in society.8

Reverend John Murray suffered a stroke in 1809, and Judith spent six years caring for him until his passing in 1815. John was working on an autobiography and was not able to finish and publish it, so Judith took over the piece and published it after financially struggling again due to John’s stroke. She later moved in with her daughter Julia and her wealthy husband. She died at the age of 69 in Natchez, Mississippi. Her family line ended in one generation after her death leaving no descendants. Her legacy lived on through her writing and she became a figure of inspiration for women across the United States. She did not publish all her work, and some of her letters and writing are still being discovered to this day.8

I want to thank those who assisted me in the process of drafting and publishing this article. I would like to thank Christopher Hohman for directing me on a path that makes my article enjoyable. I would like to thank Dr. Gawlik for assisting me throughout the drafting process. Finally a special thanks to Dr. Whitener for giving me the opportunity to write this article and being so helpful throughout the process.

- Sharon M. Harris, “Judith Sargent Murray (1751–1820),” Legacy 11, no. 2 (1994): 153. ↵

- Sharon M. Harris, “Judith Sargent Murray (1751–1820),” Legacy 11, no. 2 (1994): 153. ↵

- Sharon M. Harris, “Judith Sargent Murray (1751–1820),” Legacy 11, no. 2 (1994): 154. ↵

- Sheila L. Skemp, “A Career of Fame,” in First Lady of Letters: Judith Sargent Murray and the Struggle for Female Independence (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009), 215. ↵

- Joanna Cohen, “The Ties That Buy: Women and Commerce in Revolutionary America. First Lady of Letters: Judith Sargent Murray and the Struggle for Female Independence,” Journal of the Early Republic 30, no. 4 (Winter 2010): 653. ↵

- Sheila L. Skemp, First Lady of Letters: Judith Sargent Murray and the Struggle for Women’s Rights (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009), 269. ↵

- Sheila L. Skemp, First Lady of Letters: Judith Sargent Murray and the Struggle for Women’s Rights (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009), 266. ↵

- Christopher Cumo, “Murray, Judith Sargent (1751–1820),” in Women in American History: A Social, Political, and Cultural Encyclopedia and Document Collection, ed. Peg A. Lamphier and Rosanne Welch, vol. 1, Precolonial North America to the Early Republic (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2017), 280. ↵

- Christopher Cumo, “Murray, Judith Sargent (1751–1820),” in Women in American History: A Social, Political, and Cultural Encyclopedia and Document Collection, ed. Peg A. Lamphier and Rosanne Welch, vol. 1, Precolonial North America to the Early Republic (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2017), 280. ↵

5 comments

Martha Nava

This is a very informative and interesting article. I agree with Elliot that it is sad that she had no heirs to carry on her work. I think she was brave and strong to do what she did and to go through the struggles she had. Yet she still wanted to help other women and show them that they can also have rights and be on the same level as men. It is also cool how she opened up an all-girls academy, I am sure this helped many young women during those times.

Maria Ferrer

This article is so inspiring and motivational, especially for women. It is incredible how it only takes one person to help improve the living conditions of Women. I feel like many of us often take for granted all of the seemingly basic things in our lives, including our education. The article shows that nothing is impossible, and if we want to see a change in this world, we have to do something about it. Judith Sargent Murray is a clear example, and it is amazing how she became the first American woman to self-publish a book even with the many obstacles she had to face. The author did a great job telling her story.

Hali Garcia

I really liked this article because it was very informative over a woman I had never heard of. Judith Sargent Murray really did a lot for women and I admire how she would write about how disadvantaged women were and publish her writing to bring awareness. It is true that during this time, women had to depend on their family and husbands for everything and I like how she challenged this. Great job and congratulations on the nomination.

Phylisha Liscano

A very interesting article and very informative. I had never heard of Judith Sargent Murray and you did wonders in teaching me about her. You provided a lot of information and from the portraits of her, she looked like a very beautiful lady. Overall great article and I really enjoyed getting the chance to read your article.

Elliot Avigael

This was an interesting read, as I had never heard of Judith Sargent Murray, at least in depth. She certainly sounded like a smart, and even more so, courageous, woman to be speaking out in the manner that she did. It’s a bit of the shame that she left behind no heirs to carry on her work.