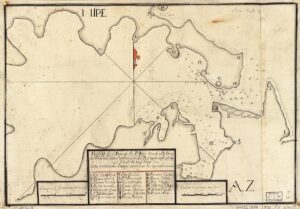

On the southeastern side of Cuba, the Caribbean Sea laps at the base of the Sierra Maestra and rolling hills rapidly ascend into towering mountains covered in giant palms and dense vegetation. For centuries, these mountains, with the help of their high elevation and rugged terrain, have served as a sanctuary for the persecuted. It is where the indigenous Taínos fled in order to escape enslavement and death at hands of the Spanish invaders in the early 1500s. Regrettably, the mountains weren’t enough to keep the Spanish away indefinitely, and by the turn of the seventeenth century, the colonizers had infiltrated the mountain range and began pillaging the region looking for resources to exploit. While they didn’t find great riches in the form of gold, they did discover a generous reserve of copper, and thus begins the story of the mining settlement of El Cobre and the miracles that happened high up in the mountains of Cuba.1

In 1599, the Spanish established the copper mining settlement of Santiago del Prado, most commonly referred to as El Cobre.2 El Cobre in Spanish simply means copper, and by colonial design, that was all El Cobre was ever supposed to be: the provider of the copper ore that the Spanish needed to produce weapons and other commodities.3 However, the cobreros, the African and indigenous slaves who worked in the copper mines, were the ones who ultimately defined what El Cobre would become: a pueblo with a distinct cultural identity that transcended the colonial order and made a lasting impact on the Catholic tradition in Cuba.

Spanish Iberian Law, protected the Catholic religious traditions of slave communities expressed in their cofradías, or faith organizations. Slave communities elected their own leaders, organized cultural and religious celebrations, and raised funds for the building of shrines and other religious monuments. The Spanish made these concessions in an attempt to reconcile the fundamental conflict between their belief in Christianity and their practice of slavery. In granting the Caribbean slaves religious “freedoms,” the Spanish claimed that while the slaves’ earthly bodies may not be free, they were spiritually liberated and therefore equals in the eyes of God. The cobrero Catholic identity that developed in the cofradías was formed through a syncretic relationship between Catholic, African, and indigenous traditions. This syncretism was representative of how the cobreros submitted to the colonial system while simultaneously forming a new cultural identity that existed outside of the jurisdiction of their oppressors. 4

In the early 1600’s, Spanish administrators oversaw the slave labor system that forced the cobreros to spend much of their time performing back-breaking work in the copper mines. With that work done, the slaves still had to produce their own food by farming the expanse of land that wove below the copper mountains. In the fertile valleys, they planted native cassava, plantains, and corn. In the expansive fields south of the mines, they raised cattle, pigs, and chickens. Then they collected salt off the northern coast to dry, season, and preserve the meat that fed the community. The people of El Cobre—men, women, and children— lived, worked, and prayed together as a community to survive within a system that asked them for everything and gave nothing in return. It was not an easy existence, but one day their prayers were answered.1

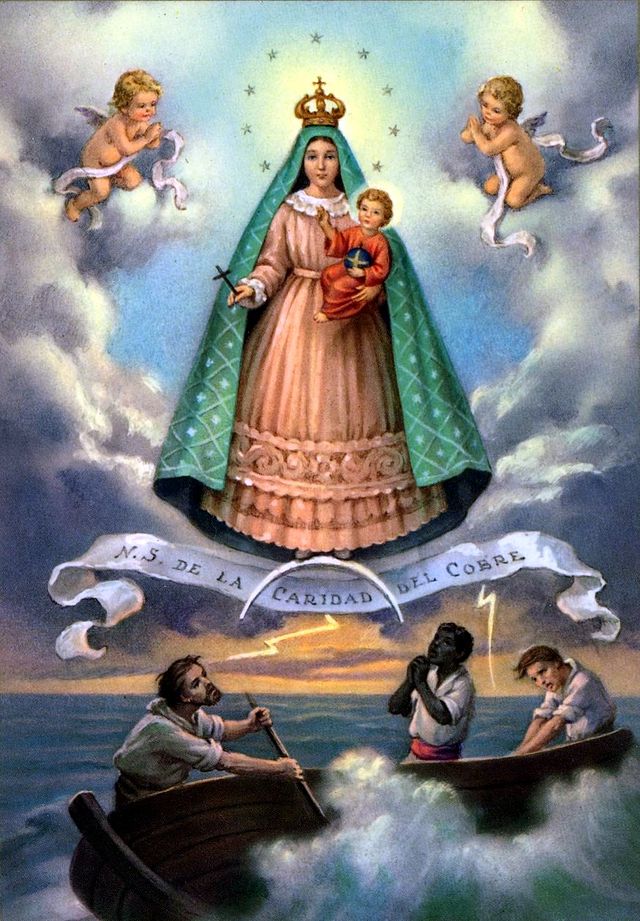

On a stormy September day, most likely in the year 1612, two indigenous brothers, Rodrigo and Juan de Hoyos, and an enslaved African boy, Juan Moreno, left their village of Barajagua with orders to collect salt in the Bay of Nipe, on Cuba’s northern coast. It was hurricane season and bad weather forced the boys to take shelter for the night in Cayo Francès, a place in the middle of the bay named for the French pirates that threatened the area.6 The next morning, ten-year-old Juan Moreno awoke before dawn to see that the storm had passed and the water had calmed. It was perfect conditions to go to the salt mines so the group set out for the salt mine. Moreno and the Hoyos brothers carried their canoe to the bay and set out to gather salt before the sun had risen in the sky. However, they didn’t get very far before one of them spotted a strange object floating on the sea foam. As their canoe got closer, they still could not make out what this object could be. Perhaps it was a bird, they thought. No, not a bird, a girl. Finally they got close enough to see that the mysterious item was neither a bird, nor a girl, but rather an image of the Virgin Mother, cradling a child with one arm and clutching a gold cross in her other hand. They rescued her from the water, and saw a wooden plaque fastened underneath her that said, “I am the Virgin of Charity.” Moreno and the native brothers marveled at the statue, amazed by the fact that even though La Virgin had been submerged in sea water, her cloth robes were completely dry. So after collecting only a fraction of the salt they were supposed to gather for the slaughter house, the boys returned to the cattle ranching town of Barajagua with news of their miraculous discovery.7

When they returned to Barajagua, on the outskirts of El Cobre, Moreno and the de Hoyos brothers presented the effigy to the Spanish foreman of the cattle ranch, Miguel Galán, and told him about the fantastic circumstances in which she appeared to them. La Virgin was then taken to one of the bohios (Taíno huts) of the village. There she was placed on a rustic altar made out of a wooden shelf, while they waited for news of her appearance to spread. Galán then passed on the story to Captain Don Francisco Sánchez de Moyo, the administrator of the mines of El Cobre. Sánchez de Moyo immediately recognized the importance of this event and sent Friar Francisco Banillo to authenticate the image.8 Once the holy effigy was validated, Sánchez de Moyo instructed Galán to erect an altar in the pastures of Barajagua and keep a lantern always lit there in tribute to La Virgin de La Caridad (The Virgin of Charity), who had honored the region through her apparition. In taking La Virgin to Barajagua and presenting her to Galán, Juan Moreno and the Hoyos brothers removed her from the natural to the Spanish socio-cultural system, and submitted her to the colonial authority. In bringing her into the colonial fold, La Virgin’s rescuers relinquished control of their discovery and put her fate in the hands of Sánchez de Moyo. The administrator of the mines could have easily dismissed the effigy as inauthentic, but instead, he validated the apparition, a decision that would soon prove to work against his own interest as a colonial official.9

By all reports, Captain Sánchez de Moyo was a genuinely pious man who was concerned about the religious lives of the slaves that he oversaw. In the first decade of the seventeenth century, he personally funded a sanctuary in the mountains in order to provide a religious education to the growing black population of El Cobre. His efforts to control not only the slaves’ lives but also their religious beliefs is in line with Spanish colonial attitudes regarding the coexistence of Catholicism and slavery. It is theorized that Sánchez de Moyo saw an opportunity in the discovery of La Virgin to attract more colonial support for the community. At the time, the Crown had just ordered residents of outlying settlements along the northern coast to relocate in order to be less vulnerable to pirate attacks, and many of these settlers chose to move to Santiago del Prado. A sign of divine favor, combined with an influx of Spaniards, would be economically advantageous for the mines of El Cobre, and in turn, for Sánchez de Moyo. Whatever his reasons were, Sánchez de Moyo’s decision to recognize the effigy was a clear turning point for the region, as the cobreros would go on to highly identify with La Virgin de la Caridad and to strategically use her image as a way to resist Spanish control. In this way, by exercising his authority over the religious lives of the slaves, Sánchez de Moyo unwittingly empowered them to subvert the social organization that he himself depended on.8

Once an official altar was built in the Barajagua pastures, it was Rodrigo and Juan de Hoyos who were the ones put in charge of taking care of the shrine. The native brothers took turns guarding the altar at night, and under their watch, further miracles began to occur. The Virgin often disappeared in the evenings and reappeared at dawn with her clothes having been soaked in water. This activity once again earned La Virgin the attention of Sánchez de Moyo, who ordered a ritual procession that would take La Virgin from the cattle fields of Barajagua to the top of the Loma de la Cantera (Quarry Hill). This procession to La Virgin’s new hermitage was to be overseen by the infantry troops and attended by the entire community. However, it became clear that La Virgin had a different resting spot in mind when glowing orbs were observed floating in the sky above Cerro de la Mina (Mine Hill), right next to the copper mines. It was clear to the people of El Cobre that these peculiar lights were La Virgin’s expressing that she wanted her resting place to be located up in the mountains near the cobreros. By choosing to be close to the slaves instead of being held by the Spanish authority, La Virgin de la Caridad defied the colonial order for the first of many times.11 What followed was years of debate concerning where the effigy should be housed. The Taínos wanted La Virgin to return to Barajagua, where she was originally found, whereas the black slaves wanted her to stay in El Cobre, where the lights appeared in the mountains; and the Spanish wanted her to be kept in the church of Santiago del Prado.12 After much contention, in 1617, the cobreros used their power as a cofradías to raise the funds needed to build the first permanent shrine to La Virgen de La Caridad. In doing so, they respected the will of La Virgin and gave her a home in the mountains in the very place that the lights had appeared, and La Virgen de la Caridad became La Virgin de la Caridad El Cobre, protectress of the cobreros and the answer to their prayers.13

In 1620, Sanchez de Moyo was replaced by Juan de Eguiluz, whose mismanagement of the mines drove the slaves to a point of potential rebellion, and consequently led to their closure in 1628. The once prosperous mines that had been supplying large amounts of copper to Havana, Seville, and Lisbon, were now unable to transport their product due to intense pirating off the coasts and bad business practices. As a result, military and religious resources were reallocated to Havana, which was now a growing metropolis, and the Spanish authority was significantly weakened in the area.14 The closure of the copper mines might have spelled financial ruin for the mines’ proprietors, but it significantly improved the lives of the cobreros. Now the free and enslaved members of the community were able to reap the rewards of their labor for the first time since the Spanish invasion. The men now had the time to cultivate the fertile soil in the valley to its full potential and were able to sell the surplus harvest for profit. With the men working in the fields, it was now the women who took over the job of mining for copper ore; they practiced alluvial mining in the rivers under the mountains. The copper ore that they collected was sold and melted down to make lamps and decorative pieces, instead of Spanish weapons. Without the mines, the cobreros were flourishing; they were able to use the profits that they earned in order to buy freedom for themselves and their families. This period of relative peace and prosperity in El Cobre lasted almost four decades, and within this time, the cobreros kinship bonds only increased and their unique cultural identity as an autonomous multi-racial community was strengthened.15 Their connection to La Virgin also grew during this time, as the presence of the Spanish church weakened, and the cobreros increasingly turned to their patroness for her blessing. When a new pastor arrived in 1648, he reported to the crown that the cobreros chose to pray at La Virgen’s hermitage instead of at the church, because they believed that she favored the community and answered their prayers. She was said to be able to heal the sick, to ensure the vitality of the harvest, and to protect the community from harm. And, as we turn the page on this chapter of El Cobre’s history, the cobreros were forced to depend on this protection for their survival.16

In 1670, the Spanish Crown confiscated the mines of El Cobre, and the authorities in Madrid began assessing their assets in the region. They found that the only resource left to monetize in the area was the 271 cobreros that remained enslaved; and so, in 1677, the king ordered an official inspection of El Cobre in order to begin the process of selling off the cobreros. This development shook the community as it threatened to separate families and ship them off to different Caribbean islands, where they would never see their homes or their loved ones again. In order to escape this horrible fate, the cobreros fled high into the mountains, carrying with them anything that could be used as a weapon: sticks, clubs, and other blunt tools. Just as the Tainos had done during the Spanish conquest, they trekked up the steep slopes and through the thick brush of the Sierra Maestra in a desperate attempt to preserve their freedom. Leading this group of about one hundred rebels, was none other than Juan Moreno, the same boy who had witnessed the Virgin’s apparition at sea. In the years that followed the discovery of La Virgin, Moreno had become a prominent figure in the community. He married a Taína woman, started a family, and for many years he served as a guardian of La Virgin’s hermitage.16 As the leader of the cobreros, Moreno entreated the king to stop the sale of his people, and in his formal petition to His Majesty, Moreno declared, “most of the people of the mines are married and we have our families that we have always sustained in a calm and peaceful way. We have been occupied in the mining works when needed, in the construction of the holy church and other tasks.” “The love for our patria (home) and our work moves us to plead, that if possible, to grant us the mercy that we stay in our pueblo, paying tribute in whatever manner is decided, while we find [the means] to [purchase] our freedom.”18

Moreno’s words legitimized the existence of El Cobre as a self-organizing community by calling upon Iberian Law that protected slaves’ rights to purchase their freedom. In referencing the cobreros’ involvement in the church, he also presented a religious defense against what the cobreros saw as a violation of their rights as a pueblo. The pleas of the cobreros were heard by the Crown, and in response to Moreno’s appeal, the king issued a decree promising that no one would be taken or sold from the lands of El Cobre. While the power of La Virgin would come to play in more obvious ways later on, her presence in El Cobre was a large part of the cobreros victory in 1677. In the time in between La Virgin revealing herself to Moreno in the Bay of Nipe and Moreno leading the rebellion into the mountains, The Mother was a constant presence in the lives of the cobreros. She worked to unify the Tainos and the black slaves, as their shared devotion to her acted as the foundation of their common culture. Without a shared cultural identity as a pueblo, the cobreros might not have been able to properly organize in order to defend their freedom. In this way, La Virgin aided her people in the first of many battles they would have to fight in order to maintain their way of life.19

After the success of Moreno’s petition, the cobreros returned to their homes and tried to go back to their peaceful lives; but the Spanish bureaucracy continued to threaten the pueblo’s existence. In the early 1700’s, the government was constantly trying to disarm the cobreros and take away their lands, efforts that were often met with strong resistance from the community. In one instance, in 1709, when Governor Don Joseph Canales tried to confiscate the farmland that fed the pueblo, the cobreros accredited their survival to La Virgin saying “had it not been for Our Lady of Charity we would have all died of hunger.”20 This conflict came to a head in 1731, when Governor Don Pedro Ignacio Ximénez mandated that all “discontented” slaves would be removed from their homes and sold. This decree was meant to send a message to the cobreros, that they should submit to Spanish authority or lose everything they held dear.21 However, it did not have the intended effect. Instead of pacifying the cobreros, it led to yet another rebellion. The cobreros, angered by Ximénez’s threat, chased the Spanish administrators out of El Cobre, and they once again marched into the mountains. On their way up, they stopped at La Virgin’s hermitage in order to bring her effigy with them. A priest later recounted this event, writing that “the said slaves had made movements attempting to take the Virgin of Charity because they said it was theirs and she was their remedy.” The cobreros also brought with them into the mountains the “king’s banner” from the village militia, as a representation of their loyalty to the Crown and of their trust in the king’s promise that they would not be taken from their lands. Their protest was a success, and the king instructed Ximénez to resend his decree, and he commanded the Spanish administration to treat the cobreros fairly. The royal slaves were once again saved from being removed from their homeland, yet their troubles were far from over.22

Throughout this time period, the cobreros often invoked the authority of La Virgin as the protectress of the community in their entreaties to the Spanish bureaucracy. In a letter to Governor Ximénez before the uprising of 1731, the cobreros begged him for clemency, writing, “in the name of Our Lady of Charity we ask you to look upon us with charitable eyes.” The cobreros believed that La Virgin had the ability to heal the pious and make ill those who threatened her venerators. This politicization of La Virgin became a key strategy implemented by the royal slaves in the litigation that would take place over the next few decades, as a result of the revitalization of the copper industry in 1780.22 At this time, the Spanish Crown relinquished the mines of El Cobre and the surrounding lands back into the hands of private owners. Motivated by the taxes that would be collected if the mines reopened, the king gave his holdings in the region back to the descendants of the original sixteenth century owners of the mines of El Cobre. When these new owners took over, they immediately made plans to sell the cobreros to far off places, like to Santiago, Havana, and even Jamaica and Cartagena. When the cobreros began to hear rumors of the sale, they followed their tradition of rebellion and marched into the mountains, yet again. However, this time, the cobreros relied more heavily on the Spanish legal system and on the protection of their patroness in order to protest their removal from their homeland.19

In an effort to exhaust all avenues of objection, the cobreros sent a representative to Madrid by the name of Gregorio Cosme Osorio. Cosme Osorio was a free man of color, who was born in El Cobre and was married to an enslaved cobrero woman. By traveling to Madrid in order to petition the crown on behalf of his people, Cosme Osorio took over the fight for freedom that Juan Moreno had begun over one-hundred years prior. In his appeal, he utilized many of the same tactics that Moreno had included in his petition back in 1677. He emphasized the cobreros’ loyalty and dedication to the crown, and argued that their status as royal slaves entitled them to certain rights and protections under the crown of Spain. While in Madrid, Cosme Osorio was constantly corresponding with his companions back in El Cobre. In their letters, the cobreros told him about the worsening conditions under the new mine owners. They related how their homes were looted, their money, jewelry, and livestock stolen, and they described the brutal floggings of men and boys that had now become commonplace. They pleaded with Cosme Osorio to make haste and come to an agreement with the king as their situation was dire, with one cobrero writing “Brother, hurry up by God, because the new masters are destroying us.” “Don’t forget Our Lady of Charity… whom I trust will help you succeed.”25

Also contained in Cosme Osorio’s writing are stories of increasingly politicized manifestations of La Virgin’s power and influence in El Cobre. Cosme Osorio and his compatriots often wrote detailed accounts of politically motivated miracles that La Virgin performed, that consisted of enemies of the cobreros being afflicted by illness or even struck down and killed by La Virgen. In one case, Cosme Osorio wrote that Don Andrés Duany, a mine beneficiary, threatened to take La Virgin away from the cobreros, as “she would free them from becoming slaves.” According to Cosme Osorio, Duany “paid his due in some days or some minutes later with a sudden acute pain that took away his life leaving his family in terror.”26 The implication was that Duany threatened La Virgin’s connection with her community, and in response, she killed him, sending a message to all those that would dare to transgress against her. Another example of how La Virgin was believed to wield her power during this time can be found in the same document as the story of Duany. In this account, Governor Don Vicente Manuel de Céspedes is ordered by the king to surrender the cobreros over to their new owners after the reprivatization of the mines in 1780. Céspedes traveled to the pueblo to act out his orders, but as soon as he arrived, his daughter fell deathly ill. Fearing that it was the retribution of La Virgin that was making his daughter sick, Céspedes brought her to La Virgin’s hermitage and by “putting a mantle of the Divine Lady over the sickly girl she found herself instantly free of illness.”26 According to Cosme Osorio, this event frightened Governor Céspedes so much that he left El Cobre without surrendering the slaves to the new mine owners. Although Céspedes’ true motivations are unknown, it is very possible that local authorities had come to fear La Virgin’s justice, as Cosme Osorio and the cobreros increasingly used their patroness as a political weapon against the Spanish authority.28

Cosme Osorio remained in Madrid, appealing to the crown on the behalf of the cobreros for almost two decades. While he was in Spain, the cobreros back home continued to resist oppression at the hands of the mine administrators through legal, violent, and supernatural means. During this time, the cobreros tradition of rebellion and their reverence for La Virgin became increasingly connected, as their religious beliefs informed their political strategy more and more. On April 7, 1800, this strategy finally paid off, and the king ordered that every cobrero would be free and have rights to their land. About a year later, in the Sanctuary of La Virgin de la Caridad, all the cobreros congregated in order to hear the royal decree be read allowed, a decree that was the answer to a struggle that spanned generations. Overlooking the celebration from her distinguished place on the altar was the effigy of La Virgin. Perhaps she was celebrating with them, for her fate was undeniably linked with that of the cobreros. From the waters of the Bay of Nipe, to the pastures of Barajagua, to the copper mountains where she picked the place for her sanctuary, the cobreros had protected her image and honored her with their ceaseless devotion. In return, La Virgin brought the cobreros together as a community. Under her protection, they became a united front against Spanish incursions and were able to defend their remarkable pueblo. With La Virgin’s help, the slaves of El Cobre secured for themselves their freedom almost one hundred years before slavery was abolished in Cuba. And although the king’s decree did not put an end to the cobreros’ struggles, the fact that they obtained the crown’s recognition of their status as the free peoples of El Cobre is quite a significant feat. Whether or not the cobreros victory was the result of La Virgin’s divine blessing is unclear. However, it is undeniable that her presence in El Cobre brought the cobreros together and it was through this collaboration that freedom was won.25

La Virgin’s work in Cuba did not end with the freeing of the cobreros in 1800, as she can be connected to many of Cuba’s most important historical events. When the Father of the Nation, Carlos Manuel de Cèspedes, declared Cuba’s independence from Spain and started the Thirty-Year War for independence in 1868, he flew a flag made of cloth taken from his family’s shrine to the La Virgen de la Caridad.25 When the war was won, the veterans of the Liberation Army petitioned the Vatican to recognize Our Virgin of Charity as the patron saint of the Republic of Cuba, a request that Pope Benedict XV fulfilled on May 10, 1916.31 In 1961 exiled Cubans in South Florida created a special shrine for La Virgin called Ermita de Nuestra Senora de la Caridad del Cobre. Tens of thousands of Cuban refugees gathered around the image of the Virgin of Cobre, a statue that had been smuggled out of a parish in Guanabo Beach, east of Havana.32 The Catholic Cuban’s who emigrated to Miami in the wake of the Cuban Revolution utilized the symbol of La Virgin in order to preserve their Cuban identity while in exile in a foreign country. For the independence fighters and the Cuban exiles, La Virgin acted as a protectress through difficult times, just as she did for the cobreros, her original venerators. Over the years, she has become one of Cuba’s most prominent national symbols. Her story is known by Cubans everywhere, whether they live in El Cobre, Havana, or even in the United Sates. However, the story of Our Lady of Charity that is told today is different from the original tale. Instead of Juan Moreno and Rodrigo and Juan de Hoyos being credited with her discovery, it is said that those who found her were all named Juan, and they have subsequently been dubbed the Tres Juanes. Depictions of the apparition in the Bay of Nipe now show the Tres Juanes as being of three different races, white, black, and of mixed descent, representing the three major racial groups in Cuba living in harmony. The evolution of La Virgin’s story contributes to the authenticity of the image as being uniquely Cuban, as she has grown from representing an obscure pueblo in east Cuba to the entire nation.33

La Virgin de la Caridad del Cobre is emblematic of Cuban nationalism. She has represented the interests of all Cubans, no matter their race, all the way back to the time of the cobreros and continuing to this day. While her origins in El Cobre and the story of the cobreros has faded from public memory, the king’s decree that liberated the cobreros contributed to a nationwide ripple effect that encouraged enslaved Cubans to campaign for their own freedom, and often just as the cobreros did, flee into La Virgin’s mountains in order to escape captivity.34 Today, high up in the peaks above El Cobre, stands the Cimarrón Monument, a stately sculpture of a hand raising out of the mountains pressing up to the sky. The sculpture by Cuban artist Alberto Lescay combines elements of African culture with natural symbolism in order to honor the runaway slaves that came to the Sierra Maestra seeking sanctuary, including the cobreros.35 If you visit El Cobre today, you will also find the Basílica Santuario Nacional de Nuestra Señora de la Caridad del Cobre, La Virgin’s current home, which sits on top of a hill overlooking the city. Her place in El Cobre is still one of honor, as she has served the community for over 400 years. The people of Cuba view La Virgin as their protectress, who serves the entire island nation and all of its people no matter their race or where they happen to reside.36

- Ada Ferrer, Cuba: An American History, First Scribner hardcover edition (New York, NY: Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster Inc, 2021), 33-34. ↵

- Olga Portuondo Zúñiga, “La Virgen de La Caridad Del Cobre,” in Cuba, vol. 2 (Detroit, MI: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2012), 1027. ↵

- Ada Ferrer, Cuba: An American History, First Scribner hardcover edition (New York, NY: Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster Inc, 2021), 34. ↵

- Anthony M. Stevens-Arroyo, “The Contribution of Catholic Orthodoxy to Caribbean Syncretism: The Case of La Virgen de La Caridad Del Cobre in Cuba,” Archives de Sciences Sociales Des Religions 47, no. 117 (2002): 45. ↵

- Ada Ferrer, Cuba: An American History, First Scribner hardcover edition (New York, NY: Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster Inc, 2021), 33-34. ↵

- Ada Ferrer, Cuba: An American History, First Scribner hardcover edition (New York, NY: Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster Inc, 2021), 34. ↵

- María Elena Díaz, “Deposition of Juan Moreno on the Apparition,” El Cobre, Cuba – UC Santa Cruz (website), accessed April 8, 2023, https://humwp.ucsc.edu/elcobre/voices_apparition.html. ↵

- Anthony M. Stevens-Arroyo, “The Contribution of Catholic Orthodoxy to Caribbean Syncretism: The Case of La Virgen de La Caridad Del Cobre in Cuba,” Archives de Sciences Sociales Des Religions 47, no. 117 (2002): 47. ↵

- María Elena Díaz, The Virgin, The King, And The Royal Slaves of El Cobre: Negotiating Freedom in Colonial Cuba 1670-1780 (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2000), 333-334 ↵

- Anthony M. Stevens-Arroyo, “The Contribution of Catholic Orthodoxy to Caribbean Syncretism: The Case of La Virgen de La Caridad Del Cobre in Cuba,” Archives de Sciences Sociales Des Religions 47, no. 117 (2002): 47. ↵

- María Elena Díaz, The Virgin, The King, And The Royal Slaves of El Cobre: Negotiating Freedom in Colonial Cuba 1670-1780 (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2000), 100. ↵

- Anthony M. Stevens-Arroyo, “The Contribution of Catholic Orthodoxy to Caribbean Syncretism: The Case of La Virgen de La Caridad Del Cobre in Cuba,” Archives de Sciences Sociales Des Religions 47, no. 117 (2002): 48. ↵

- Ada Ferrer, Cuba: An American History, First Scribner hardcover edition (New York, NY: Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster Inc, 2021), 35. ↵

- Anthony M. Stevens-Arroyo, “The Contribution of Catholic Orthodoxy to Caribbean Syncretism: The Case of La Virgen de La Caridad Del Cobre in Cuba,” Archives de Sciences Sociales Des Religions 47, no. 117 (2002): 48-49. ↵

- Ada Ferrer, Cuba: An American History, First Scribner hardcover edition (New York, NY: Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster Inc, 2021), 36. ↵

- Anthony M. Stevens-Arroyo, “The Contribution of Catholic Orthodoxy to Caribbean Syncretism: The Case of La Virgen de La Caridad Del Cobre in Cuba,” Archives de Sciences Sociales Des Religions 47, no. 117 (2002): 49. ↵

- Anthony M. Stevens-Arroyo, “The Contribution of Catholic Orthodoxy to Caribbean Syncretism: The Case of La Virgen de La Caridad Del Cobre in Cuba,” Archives de Sciences Sociales Des Religions 47, no. 117 (2002): 49. ↵

- Maria Elena Diaz, “Petition of Slave Captian Juan Moreno, 1977,” El Cobre, Cuba – UC Santa Cruz (website), accessed April 8, 2023, https://humwp.ucsc.edu/elcobre/voices_petition.html. ↵

- Ada Ferrer, Cuba: An American History, First Scribner hardcover edition (New York, NY: Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster Inc, 2021), 36-37. ↵

- María Elena Díaz, The Virgin, The King, And The Royal Slaves of El Cobre: Negotiating Freedom in Colonial Cuba 1670-1780 (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2000), 110. ↵

- Ada Ferrer, Cuba: An American History, First Scribner hardcover edition (New York, NY: Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster Inc, 2021), 37. ↵

- María Elena Díaz, The Virgin, The King, And The Royal Slaves of El Cobre: Negotiating Freedom in Colonial Cuba 1670-1780 (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2000), 110-111. ↵

- María Elena Díaz, The Virgin, The King, And The Royal Slaves of El Cobre: Negotiating Freedom in Colonial Cuba 1670-1780 (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2000), 110-111. ↵

- Ada Ferrer, Cuba: An American History, First Scribner hardcover edition (New York, NY: Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster Inc, 2021), 36-37. ↵

- Ada Ferrer, Cuba: An American History, First Scribner hardcover edition (New York, NY: Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster Inc, 2021), 38. ↵

- María Elena Díaz, The Virgin, The King, And The Royal Slaves of El Cobre: Negotiating Freedom in Colonial Cuba 1670-1780 (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2000), 108. ↵

- María Elena Díaz, The Virgin, The King, And The Royal Slaves of El Cobre: Negotiating Freedom in Colonial Cuba 1670-1780 (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2000), 108. ↵

- María Elena Díaz, The Virgin, The King, And The Royal Slaves of El Cobre: Negotiating Freedom in Colonial Cuba 1670-1780 (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2000), 108-109. ↵

- Ada Ferrer, Cuba: An American History, First Scribner hardcover edition (New York, NY: Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster Inc, 2021), 38. ↵

- Ada Ferrer, Cuba: An American History, First Scribner hardcover edition (New York, NY: Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster Inc, 2021), 38. ↵

- Olga Portuondo Zúñiga, “La Virgen de La Caridad Del Cobre,” in Cuba, vol. 2 (Detroit, MI: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2012), 1028. ↵

- Gerald E. Poyo, Cuban Catholics in the United States, 1960-1980 (Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press, 2007), 105-107. ↵

- Ada Ferrer, Cuba: An American History, First Scribner hardcover edition (New York, NY: Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster Inc, 2021) 38. ↵

- Ada Ferrer, Cuba: An American History, First Scribner hardcover edition (New York, NY: Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster Inc, 2021), 39. ↵

- Maria Elena Lopez, “The Cimarrón: A Cuban Monument of Resistance to Slavery,” Cuba 50 (blog), June 30, 2020, https://cuba50.org/2020/06/30/the-cimarron-a-sculpture-commemorating-resistance-to-slavery/. ↵

- Olga Portuondo Zúñiga, “La Virgen de La Caridad Del Cobre,” in Cuba, vol. 2 (Detroit, MI: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2012), 1029. ↵

42 comments

Sudura Zakir

hello Lauren I appreciate you for the nomination! First of all, let me mention that this article was quite insightful about La Virgin de la Caridad del Cobre, a stunning piece of art. Because of its unusual past and my belief in supernatural and eternal spirits, learning that it was used for her benefit is genuinely admirable and needs to be given due respect.

Joseph Frausto

Congratulations on the win at the research awards. I find this article very interesting considering how well known the story of the Virgin de Guadalupe is among Mexican American communities. Seeing similar stories arise in other Latin American cultures is very interesting to me, especially the fact that the slave trade and its place in Cuban history both play major roles in this article. Great job!

Fernando Milian

What an interesting article, and what an excellent way to tell that story. Even though I am from Cuba, I have to say that I did not know that story so well. Yes, it is true that the Virgin it’s very popular in Cuba, even among people that are not even religious and people of all ages, but not everyone knows the story of how the Virgin was found. I once had the opportunity to visit the Basílica Santuario Nacional de Nuestra Señora de la Caridad del Cobre in Santiago de Cuba. It is a beautiful place, full of calm and tradition. So many people go to visit asking for miracles or simply showing gratitude. Keep up the good work! Well done!

Aaron Astudillo

This was such a great article that sheds a light on the history of Cuba and the origin of a figure that impacted this country. The cultural significance of La Virgina de la Carded del Cobre is outstanding as it gave the Cuban population the spirit to fight in the battle for their lives.

Maximillian Morise

This was a great article on Cuban history and giving insight on a historical matter that is not often known or talked about! Congratulations for your nomination, and thank you for this well-research topic!

Kaylah Garcia

Lauren, congratulations on your nomination and your article. This piece was simply stunning. I liked how you mentioned being able to accurately convey the past while tying it to Cuba’s future/present. La Virgin de la Caridad del Cobre really shown courage and protection for the Cubans, and it was a lovely narrative to read. The miracles that occurred here were quite astounding.

Noelia Torres Guillen

I loved this article and learned so much from it. I got to understand the origin and cultural significance La Virgin de la Caridad del Cobre has on Cuba. La Vigin de la Caridad del Cobre protected Cubans and gave them hope to gain freedom. I got to appreciate religion a bit more than usual. Everyone needs hope especially in dark times. You told this story well, and congratulations on your nomination.

Lauren Deleon

Thank you so much Noelia for reading my article! I am so glad that you enjoyed it!

Vincent Villanueva

Hi Lauren! Congratulations on your nomination! I would first like to say that this article was super insightful article about La Virgin de la Caridad del Cobre which is such a beautiful work of art. Its history is so unique and as a believer in a super natural and immortal spirits, hearing the use for her good is something that is truly respectable and it deserves the proper recognition.

Lauren Deleon

Thank you so much Vincent! It so great to hear that you appreciate the significance of La Virgin as a cultural and religious figure.

Barbara Ortiz

Congratulations on your nomination for such a great article, Lauren. I really enjoyed reading and learning about the Patroness of Cuba. The image and the spiritual value of la virgen is likened to that of Our Lady of Guadalupe for Mexico, and aided the people (Tainos and black slaves) in their battles to fight to maintain their way of life. Well done!

Lauren Deleon

Thank you so much Barbara for reading my article! I am so glad you enjoyed it and were able to connect the story of La Virgin de la Caridad to Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe.

Luke Rodriguez

Congrats on the nomination. It was well-deserved! Before reading this article, I knew nothing about this. This was a very interesting article, and I found this very informative. The Virgen de la Caridad del Cobre is an amazing symbol for the Cuban people. The Spanish tried to justify the enslavement of the mountain communities through God, which I found interesting. Cobreros were freed by La Virgin since they believed in God.

Lauren Deleon

Thank you so much Luke! I am so glad you enjoyed learning about La Virgin.