The Sixties were filled with new fashions, great music, break-through technologies—and lots of protests. Some protests advocated for Civil Rights, while many sought to put an end to the Vietnam War. The Vietnam War dominated the mid-to-late sixties and taught American elected officials the limits of their powers and their failure to play the role of an international patrol. Americans were angered by the atrocious behavior that the U.S. government used to prevent Communism from taking over Vietnam. This caused some of the largest protests in American history, with protesters ranging from businessmen and women to long-haired hippies. The United States foreign policy in Southeast Asia caused great debates among Americans, and the Vietnam War also became notoriously known for being a battle between the U.S. government and its citizens.

During the Kennedy administration, the United States initiated its struggle to prevent Communism from taking over Vietnam. Desperate to achieve success, the newly elected President John F. Kennedy approved the assistance of advisers to support the Army of the Republic of (South) Vietnam (ARVN) and he authorized the use of chemical herbicides, such as Agent Orange and napalm. Although Presidents Truman and Eisenhower provided resources to help France combat communism, it was President Kennedy that deepened this commitment. During his presidency, the number of American military advisers sent to Vietnam reached 12,000. Then, in November 1963, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) had the U.S.-appointed South Vietnamese leader Ngo Diem and his brother killed. Twenty-one days later, President Kennedy was assassinated.1

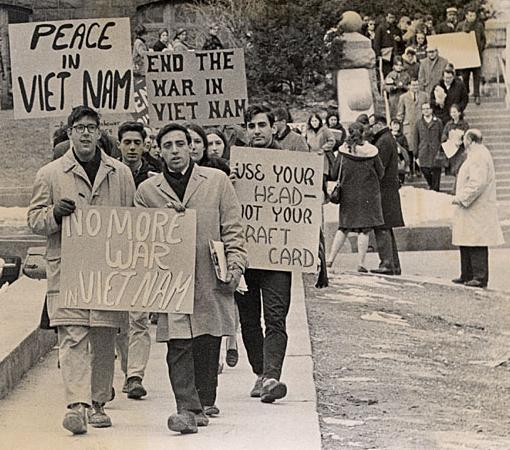

The insurgence of U.S. involvement in Vietnam caused protests in the United States by religious leaders, students, workers, and minorities. Americans were against the United States’ approach to “containing” Vietnam’s communism. Such protests started out on college campuses, where many students and professors dedicated their time to criticizing American policy. Students organized boycotts, marches, strikes, teach-ins, and sit-ins. Some even appeared at their universities with Vietcong flags and chanted, “Hey, hey, LBJ. How many kids did you kill today?”2 Typically, such protests were put down by police officers using tear gas and nightsticks or by arresting students. Protests grew and became even more popular after Congress passed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution in 1964, which gave the president unlimited war powers.3

As the first televised war, with television networks having full-time teams in Vietnam, Americans changed the way they thought about the war. Americans watched the atrocities that Vietnamese civilians were facing every night from their living rooms. This worsened when Johnson’s administration announced that more than fifty thousand men were being drafted to go to Vietnam. The first U.S. ground troops arrived in Vietnam on March 8, 1965, immediately followed by a sequence of U.S bombings of defoliants flown over North Vietnam known as Operation Rolling Thunder. Once again, this caused distress across America, and in response, the University of California-Berkeley created the International Days of Protests on October 15 and 16 as the official days for anti-war protests to occur across the United States. Other civilians had stronger responses to this, such as that of peace movement activist Alice Herz. Herz urged Americans to become aware of the issue in Vietnam, and she gained recognition as the first person in the United States to burn herself to death in protest to Operation Rolling Thunder.4 To address this, President Johnson went to Johns Hopkins University on April 7, 1965 to give a speech that pleased many Americans as he reiterated the motives behind the war, “We want nothing for ourselves—only that the people of South Viet-Nam be allowed to guide their own country in their own way.”5

The rise in support did not last long as radical groups continued to hold even more protests. On April 17, 1965, the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) held the first major anti-war protest in Washington, D.C.6 There, they created the famous slogans of the period, “Make Love, Not War” and “Burn Cards, Not People.” Four months later, the first International Days of Protests occurred. Over 100,000 protesters gathered in Washington, D.C. and in New York City to rally against the war, and it was there where the first person publicly burned his draft card.

Protests also broke out in several high schools, including an important protest in Des Moines, Iowa. Several high school students decided to wear black armbands to school as a way to demonstrate their opposition to the war. Once the students arrived at school, the administrators ordered the students to remove the armbands or they would be suspended. When two students, Mary Tinker and John Tinker, refused to remove their armbands, they were suspended. Their parents sued the school district and the case wound up in the Supreme Court. In Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District, the court ruled that the students had the right to freedom of speech even when they were on school property under the First Amendment.7

The war was not only worsening in Vietnam, as the number of American casualties grew, but it also became more crucial in the United States. Opponents focused on posting newspaper ads with signatures of men saying they would not fight the war; others burned American flags, or performed alternative service to avoid being drafted; and some even fled the country, with at least 1,000 Americans migrating to Canada to avoid the draft.8 Americans were even more critical of the war when President Johnson asked Congress to implement a 10-percent surtax to the federal income tax as a “special wartime surcharge on individual and corporate income taxes.”9 At first, his request was fought by many, but by June of 1968, Johnson signed the Revenue and Expenditure Control Act.10 The act would go through the mid-1970s to help raise enough money to fund the war. Even though it exempted low-income taxpayers, many Americans refused to pay their taxes, including two celebrities, Joan Baez and Jane Fonda.

Disputes between government officials, minority groups, and religious groups surfaced. One of the first government officials to speak against the war was the Chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and Arkansas Senator, James William Fulbright. Minority groups protested against racism, poverty, and the U.S. policy in Southeast Asia. Mexican Americans formed the National Chicano Moratorium Committee, which then formed the Chicano/a Movement. At first, the movement supported President Johnson due to his responsiveness and recognition of Mexican Americans as an “estimable class of Texas citizens.”11 President Johnson continuously emphasized his desire to eliminate poverty and racism. However, when promises were not being accomplished because “budget cuts that hurt impoverished minorities” were linked to “the cost of the ongoing war in Viet Nam,” many were angered.12 Some Mexican Americans related to the injustices that Vietnamese civilians encountered because they were “both members of the Third World in that both were a non-white people suffering from the exploitative nature of U.S. imperialism and capitalism.”13

At the same time, religious groups and some minority groups approved of the war at first. American Roman Catholics, including Catholic church officials, supported the war primarily for their opposition to communism according to their religious ideology. However, some bishops resigned their positions and founded an organization called the Clergymen’s Emergency Committee for Vietnam, with over two thousand ministers, rabbis, and priests signing an advertisement that stated, “In the Name of God, Stop it!!”14 Jewish Americans and African Americans were more likely to be supporters of the war, mainly because of their loyalty to President Johnson. Jewish Americans were hostile to the Soviet Union because of the heinous treatment of Jews during World War II. Nonetheless, this changed with the election of President Richard Nixon, with fear that if they opposed American foreign policy, it would recreate Antisemitism. Simultaneously, African Americans were unlikely to oppose the war due to the recent signing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 by President Johnson, along with his creation for the Great Society programs. Although, when Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. stated that the “war had spread beyond its physical horrors to wreck the Great Society and threaten American principles and values,” many African Americans began to oppose the war.15

Another anti-war protester was heavyweight boxing champion Cassius Clay, also known as Muhammad Ali. When he was told that he was being drafted into the war, he refused to serve and claimed to be a conscientious objector. Then in June 1967, he was convicted of draft evasion, for which he was sentenced to five years in prison, fined $10,000, and had his boxing license removed for three years. To this Ali stated,

It is in the light of my consciousness as a Muslim minister and my own personal convictions that I take my stand in rejecting the call to be inducted. … I find I cannot be true to my beliefs in my religion by accepting such a call. I am dependent upon Allah as the final judge of those actions brought about by my own conscience.16

Ali conducted speeches at universities about his opposition, while also trying to appeal his conviction. Finally, in 1971, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Ali’s conviction in Clay v United States. The Justices ruled that Ali did meet the requirement of two of the three basic tests for conscientious objector status.17

The war promulgated an even greater problem among American soldiers in Vietnam, particularly drug abuse. Because drugs, including heroin, opium, and cocaine, were incredibly cheap, several GIs became addicted to them. By the late 1960s, the U.S. government had to implement testing and rehabilitation programs to control drug abuse by American soldiers. The draft system in the United States typically drew on minorities and working-class citizens, which provoked many anti-draft protests. Young Americans enrolled in college as a way to receive “college deferments…that delayed their eligibility for conscription.”18 While some were able to flee the country, low-income individuals and minorities had no option but to join. While in Vietnam, soldiers, also referred to as GI’s—government issue or general infantry—knew that their mission was to “kill the Communists and to kill as many of them as possible.”19 It had been recorded that few radical opponents believed U.S. soldiers were “willing agents of a racist and imperialist foreign policy that had become America’s chief way of dealing with the Third World in the twentieth century.”20

In January 1968, when millions of Americans believed the U.S. was winning the war, North Vietnamese troops and Vietcong soldiers attacked multiple cities in South Vietnam in a mission known as the Tet Offensive. The name Tet was given by North Vietnamese troops in honor of the Vietnamese Lunar New Year. In retaliation, the U.S. sent more than half a million U.S. soldiers to Vietnam. Shorty after, in early February 1968, America’s most trusted man and CBS Evening News anchorman Walter Cronkite, traveled to Vietnam to cover the truth and impacts of the Tet Offensive. As the “voice of truth for America,” his commentary in Vietnam had a major impact on Americans.21 Upon his return, Cronkite delivered his famous “Report from Vietnam.” His report indicated that the war was “mired in stalemate” and proposed that the only way out was through an honorable peace.22 Americans were shocked to hear that the U.S. was dishonest about the war and thus, many Americans no longer supported the war nor President Johnson. It is believed that this is what caused President Johnson to announce that he would not seek re-election in 1968.

After President Johnson refused to run for reelection, Republican candidate Richard Nixon won the election by campaigning that he planned to end the war through “peace with honor.”23 His proposal, known as “Vietnamization,” aimed to strengthen South Vietnamese troops to fight the war and slowly remove American troops. By 1969, the U.S. withdrew 25,000 troops from Vietnam. In order to avoid anti-draft protests, President Nixon implemented the Commission on All-Volunteer Force, which drafted men based on their criminal records and those that volunteered. His popularity did not last as long as he expected, since it was publicized that he approved the secret invasion of Cambodia in April 1970, hid American mortalities, and spied on U.S. citizens that protested the war. This led to the revitalization of protests across the United States, with one of the largest created by the New Mobilization Committee to End the War named the “March against Death” on November 13 and 15, in which every protester carried a sign with the name of an American killed in Vietnam. Meanwhile, many pro-war urban laborers called on peace demonstrators to “Go back to Russia” and carried posters that read “America, Love it or Leave It.”24

Some Americans became even more adamant about putting an end to the war by using violence and rebelling against the U.S. government. An organization called Weather Underground placed a bomb in the Capitol in Washington, D.C. to protest the U.S. invasion in Laos. Although nobody was hurt, it cost $300,000 in damages.25 In April 1971, hundreds of mothers of American soldiers that were killed in Vietnam and Vietnam veterans united to march to the Capitol. Known as Operation Dewey Canyon III, GIs threw the medals and ribbons they earned in Vietnam onto the steps of the building. A month later, the 1971 Mayday anti-war protest in Washington, D.C. was held from May 1st to May 3rd. It aimed to shut down all federal government offices to demonstrate to President Nixon that Americans would not cooperate unless the war was put to an end. As a result of the Mayday protests, more than 13,000 people were arrested.26

To make matters worse, on June 13, 1971, the New York Times published classified government documents concerning the Vietnam War, known as the Pentagon Papers. The papers showed that the administration claimed that the reason the U.S. continued in the war was, “70% to avoid a humiliating U.S. defeat; 20% to keep South Vietnam (and adjacent territories) from Chinese hands; 10% to permit the people of Vietnam a better, freer way of life” and revealed that the U.S. had no chance at succeeding.27 In response, the U.S. Congress repealed the 1964 Gulf of Tonkin Resolution on December 31 and created the Cooper-Church amendment to stop the funding of the invasion in Cambodia. Two years later, the United States and North Vietnam signed the Paris Peace Accords, which agreed to end the war. By August, Congress passed the Case-Church Amendment that banned all funding for military activities in Vietnam. Finally, the last U.S. combat troops left Vietnam in 1973. Consequently, South Vietnam’s economy collapsed and what had been prevented for over ten years finally occurred: Vietnam fell into the hands of Communism.

The Vietnam War was not only a war against communism but also a war in America. The United States’ decision to interfere in the Vietnamese battle for independence and fight against North Vietnam created great debates in America. Television, newspaper and magazine networks dedicated a lot of their time to the war. The opposition to the war was also given recognition by many politicians, celebrities, and writers who contributed to the movement by signing ads, raising funds, and endorsing peace candidates. Even Hollywood films were created in response to the American protests against the government’s involvement in Vietnam, such as Bonnie and Clyde (1967), Easy Rider (1969), and M*A*S*H (1970). This war has been one of the longest and most controversial wars in American history. It instigated some of the largest protests, marches, sit-ins, and strikes all across the country that will always be remembered.

- Robert Freeman, The Vietnam War: The Best One-Hour History (Palo Alto, CA: Kendall Lane Publishers, 2013), 6-11. ↵

- David W. Levy, The Debate over Vietnam (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 1995): 135. ↵

- Robert Freeman, The Vietnam War: The Best One-Hour History (Palo Alto, CA: Kendall Lane Publishers, 2013), 12. ↵

- Jon Coburn, “”I Have Chosen the Flaming Death”: The Forgotten Self-Immolation of Alice Herz,” Peace & Change, 43, no. 1 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1111/pech.12273. ↵

- Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States: Lyndon B. Johnson, (1965) Volume I, entry 172, Washington, D. C.: Government Printing Office (1966), 394-399. ↵

- William W. Riggs, “Students for a Democratic Society,” Students for a Democratic Society. Accessed March 27, 2020. https://mtsu.edu/first-amendment/article/1201/students-for-a-democratic-society. ↵

- Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District 393 US 503 (1969). ↵

- Tom Hayden, Long Sixties: From 1960 to Barack Obama (Routledge Press, 2015), 208. ↵

- Joseph J. Thorndike, “Historical Perspective: Sacrifice and Surcharge,” TaxAnalysts, December 2005. http://www.taxhistory.org/thp/readings.nsf/cf7c9c870b600b9585256df80075b9dd/6b24abb33fe1996c852570d200756a5d?OpenDocument. ↵

- Revenue and Expenditure Control Act of 1968: explanation of the bill H.R. 15414 as agreed to in conference, Revenue and Expenditure Control Act of 1968: explanation of the bill H.R. 15414 as agreed to in conference § (1968). ↵

- Lorena Oropeza, Raza Si!, Guerra No: Chicano Protest and Patriotism during the Viet Nam War Era (University of California Press, 2005), 50. ↵

- Lorena Oropeza, Raza Si!, Guerra No: Chicano Protest and Patriotism during the Viet Nam War Era (University of California Press, 2005), 58. ↵

- Lorena Oropeza, Raza Si!, Guerra No: Chicano Protest and Patriotism during the Viet Nam War Era (University of California Press, 2005), 95. ↵

- David W. Levy, The Debate over Vietnam (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 1995), 100. ↵

- Martin Luther King Jr., “The Casualties of the War in Vietnam,” Atlantic, (1967): 93. ↵

- DeNeen L. Brown, “’Shoot Them for What?’ How Muhammad Ali Won His Greatest Fight,” The Washington Post. WP Company, June 16, 2018. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/retropolis/wp/2018/06/15/shoot-them-for-what-how-muhammad-ali-won-his-greatest-fight/. ↵

- Clay v United States 403 US 698 (1971). ↵

- David Card and Thomas Lemieux, “Going to College to Avoid the Draft: The Unintended Legacy of the Vietnam War,” The American Economic Review 91, no. 2 (2001): 97. ↵

- James Lewes, Protest and Survive: Underground GI Newspapers during the Vietnam War (Praeger, 2003), 2. ↵

- David W. Levy, The Debate over Vietnam (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 1995), 60. ↵

- Biography.com Editors, “Walter Cronkite Biography,” A&E Networks Television, October 31, 2019. https://www.biography.com/media-figure/walter-cronkite. ↵

- Walter Cronkite, Report from Vietnam, New York, New York: CBS News, February 27, 1968. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Dn2RjahTi3M. ↵

- Richard Nixon, “Address to the Nation Announcing Conclusion of an Agreement on Ending the War and Restoring Peace in Vietnam – January 23, 1973 ” Richard Nixon Foundation,” Richard Nixon Foundation, August 18, 2017. https://www.nixonfoundation.org/2017/08/address-nation-announcing-conclusion-agreement-ending-war-restoring-peace-vietnam-january-23-1973/. ↵

- David W. Levy, The Debate over Vietnam (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 1995), 113. ↵

- “Bomb Explodes in Capitol Building,” History.com. A&E Television Networks, November 16, 2009. https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/bomb-explodes-in-capitol-building. ↵

- Yulia Senina, “Washington, DC Protests against the War in Vietnam (Mayday), 1971,” Global Nonviolent Action Database, February 3, 2012. https://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu/content/washington-dc-protests-against-war-vietnam-mayday-1971. ↵

- “193. Paper Prepared by the Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security Affairs (McNaughton),” U.S. Department of State. U.S. Department of State, Accessed March 24, 2020. https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1964-68v02/d193. ↵

30 comments

Matthew Avila

this article was very informative. when I was being taught about the Vietnam war I was taught more about the fighting and what happened in Vietnam rather than what was happening in the US. this is a great explanation of what was happening in the country during wartime. I believe that we did more harm than good in Vietnam and I would’ve stood with everyone that was protesting.

Thiffany Yeupell

From its inception, the Vietnam War was a mess to handle and finish. The presidents had to deal with the foreign opposing forces overseas and the internal protesting back home, leaving a difficult situation to navigate through, which essentially resulted in a lose-lose for the US. A nation at war will most likely not succeed overseas, if the support back home is small to nonexistent, for the approval of ones’ citizens holds immense influence and power.

Giselle Garcia

This was an article that explained in detail very well about the protests of the Vietnam War in the United States. I learned a lot of interesting events that happened that I didn’t really understand fully. I was surprised that different religious groups and ethnic groups reacted to the war and individuals carried out protests. I was intrigued by the students wearing armbands in opposition of the war to school, but were suspended by the school when they refused to take their armbands off. This demonstrated well how far the protestors were willing to go to get their message across.

Andrea Degollado

I think this was was quite interesting. This article really highlights how chaotic the united states was during the time of the Vietnam War. I had learned about the Vietnam War in one of my history classes, but I was able to gather new knowledge by reading this article. In addition I found it very interesting to read how, this was the first war where media was involved and how it essentially changed information to travel. Great article, very well written.

Vanessa Barron Ortiz

Very well written article! I have done my fair share of research papers in high school over events happening during this time. These people were frustrated with the way the government was running their country. How could they have allowed this to have happened for so long? So many people during this era where not afraid to speak there mind, whit I think was a good thing because if it had not been for the protesters, our way of living would be different.

Aiden Dingle

I think that the Vietnam War is a really interesting thing. It was the first war where soldier weren’t really moving to capture any specific objectives like cities, and of course it was the first war that the American Public strongly opposed. One of the most interesting things that came out from this article and the Vietnam War itself has to be how much control the media has over the American public. This was the first war that was televised to the people, for the first time, the public was able to see how the war was going day to day without any real filters from the government. The information was also available to them right away because it was televised, no one had to wait for a newspaper. It’s just really interesting to see how much the media could change, and the protests against the Vietnam War is an excellent example to see what the media could really do.

Kendall Guajardo

Great well written article! Even with all of the various information mixed in, it was all very chronological and easy to follow. There were a lot of interesting facts I learned from reading this. One that stood out was Muhammad Ali being an anti-war protester and avoiding the draft. I liked how you explained the perspectives from various religious and ethnic groups at the time. There was a large failure to this war as reading that the reason for its continuance was just to appear as victors and not losers of the war. There was amazing resilience shown by the American people during this time and it was very cool to see the different demonstrations and activism.

Sofia Almanzan

Great Article! in being a political science major I appreciated the fact that you talked about Tinker vs Des Moines because it really plays into the political culture of the time. Many Supreme Court decisions are a result of the people on the court and the culture they are in and this showed the culture during the Vietnam War.

Davis Nickle

This article really sends home the fact of just how chaotic and tumultuous the United States was at the time of the Vietnam War. I think its safe to say that the entire country was at a boiling point and I firmly believe that between the civil rights protests and the war tensions could not have been higher. I was also surprised to learn that the first American self immolation happened in protest to Vietnam. This was an incredibly interesting read.

Lulu Guadalupe Avitua-Uviedo

very interesting article. As an organizer and activist myself I understand the use and force of my voice. A very good friend of mine served in Vietnam, he was drafted right before his high school graduation and had to put aside his full paid scholarship to Notre Dame. He told me, the Vietnam war should never have happened and the veterans have never gained respect from that war. He also mentioned how many of his friends wanted to go to Canada rather than go to Vietnam. Many protestors from that era still speak of how violent and unjustly the Vietnam war was, their voice carry pain and anger all mixed into one in their words. Good writing.