Xiao – Filial Piety

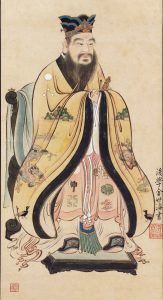

Xiao, or filial piety, is a virtue of respect for one’s parents, elders, and ancestors in societies influenced by Confucian thought. Filial generally means “concerning a parent-child relationship” and piety means “dutiful respect.” Together, filial piety refers to a child’s service toward their parents as well as older extended relatives. Filial piety is a Confucian value. “Confucius [551-479 B.C.E., a Chinese philosopher, politician, and teacher] specified that two ethical principles should guide social interaction: favoring the intimate (giving preference to those with whom one is closest) and respecting the superior (giving deference to those who are older)”1 Filial piety is a core pillar of Confucian ethics because it shows deference to one’s elders. Confucius believed that one must demonstrate filial piety by respecting their parents during their life and after death. He said that one should make no changes to the ways of his father for three years after his father has passed away to become a filial son. However, Mozi “Mo” (470-391 B.C.E.), a later Chinese philosopher, challenges Confucius’ view of filial piety. Mozi says that filial children must plan three benefits on behalf of their parents: to enrich the poor, increase the population, and bring order to chaos. Because of this, Mozi argues in contrast to Confucius that lavish funerals and prolonged funerals are neither benevolent nor right, and are not the obligations necessary for maintaining filial piety in children. In this paper, I will defend Mozi’s view that lavish funerals and prolonged mourning are not the obligations necessary for maintaining filial piety in children.

Confucius’ Three Year Mourning Period

Confucius states that a filial son should mourn for three years after his father or mother has passed. “A child is completely dependent upon the care of his parents for the first three years of his life- this is why the three-year mourning period is the common practice throughout the world.”2 A parent takes care of their child when they are completely helpless for the first three years of their life, so a filial child should mourn the death of their parents for the first three years to pay back the same respect. “Filial piety is partially constituted by the sense that the kindness one has received was done by someone who was dramatically more powerful than oneself and who sacrificed substantial goods of their own to care for one in these ways.”3 The three year mourning period is supposed to be a sad and sacrificial period for a child to think about their parents and remember them for that dedicated amount of time. During three year mourning period, a child gives up pleasures such as sweet food, music, and their home after their parent dies.

Confucius also stated that a filial child undergoes emotions of sadness after the death of their parents. As one is in a state of mourning, pleasures shouldn’t be as appealing to one. As such, a filial child should have no desire for these things because they are suffering due to their attachment to their parent or elder. If one truly honored and cared about the loss, then the usual joys of life would no longer bring joy and ease, but instead only increase anxiety and feelings of loss. “When the gentleman is in mourning, he gets no pleasure from eating sweet foods, finds no joy in listening to music, and finds no comfort in his place of dwelling. This is why he gives up these things.”4 Confucius wanted the sacrifices to not be given up out of ritual, but out of emotion and sadness. “For the ‘three-year mourning period’, Confucius makes it abundantly clear that mourning must reflect genuine grief.”5

Mozi’s Argument in Contrast to the Three Year Mourning Period

Mozi challenges Confucius’ view of mourning and lavish funerals to become a filial child by arguing that it is neither benevolent nor right. “Mo Zi studied Confucian works and accepted Confucius’s techniques, but found their rituals complicated, troublesome, and unappealing, thinking that elaborate funerals wasted resources and impoverished the people, caused injury to the living, harmed service.”6 Instead, Mozi states that a filial child’s task is to benefit their parents. “Loving one’s parents may gain an individual reputation for being filial, but the benefits accruing to his parents are the actual result. …When the love of one’s parents is constructed on a basis of benefitting one’s parents, only then is it really filial piety.”7 He argues that excessive mourning and lavish funerals do not benefit one’s parents, and he lists the three ways that filial children can benefit their parents.

“If their parents are poor, do what they can to enrich them. If the members of their clan are few, they do what they can to increase their numbers. If the family is in chaos, they do what they can to make it well ordered. In pursuing these ends they might find out that their strength is insufficient, their resources inadequate, or their knowledge too limited, and that they fall short. But they would never hold back any of their strength or any scheme or advantage and not apply these in their efforts to realize their parents’ well-being.”8

In simpler terms, the three benefits of filial children on behalf of their parents are to enrich the poor, increase the population, and bring order to chaos. Mozi then describes the rules and behaviors for one in mourning to help us to understand the restrictions of the mourning period. “Moreover, they are to encourage each other to refuse food and starve themselves. … The most noble of people uphold the rites of mourning to the point where they cannot rise up without assistance and cannot walk without a cane and they follow these practices for three years.”9 This shows the severity of the mourning period to the point of starvation and making oneself weak.

Mozi then argues that the mourning period does not enrich the population by describing what will happen when kings, officials, farmers, craftsmen, and women go into mourning. “Should kings, dukes, and other great men follow such practices, they will not be able to… carry out the affairs of government. Should farmers follow such practices, they would be unable to… carry out the ploughing, planting, and tending of crops. And so… prolonged mourning entails prohibiting people from pursuing their vocations for an extended period of time.”10 The amount of material labor from these groups of people would be adversely impacted during the mourning period, and it will not enrich the population if they do not work. Mozi also offers evidence of how following extended mourning can lead to population decrease. “If the people starve themselves in this manner then they will be unable to withstand the cold of winter or the heat of summer and countless numbers of them will grow ill and die. This greatly diminishes the chances for men and women to procreate.”11 Mourning does not increase the population because people are starving themselves to death, and it does more harm than help.

Mozi further questions the overall impact the mourning period can have on families, saying that it causes children to become disrespectful to their parents due to the restrictions of the period. While Confucius states that the mourning period is supposed to be a task of filial children, Mozi argues that the mourning period has the opposite effect and causes children to become unfilial to their parents. “If those… are unable to attend to their affairs, then the government would be in chaos. If those below are unable to pursue their various tasks, then food and clothing will be in short supply. Children who seek… such things from their parents will be refused and… come to feel unfilial.”12 In conclusion, Mozi argues that the mourning period brings more harm than help. The state would be poor, the people few, and the government in chaos and therefore, prolonged mourning should not be a task of filial children.

Modest Funerals and Sacrificial Offerings

The way to show filial piety, for Mozi, is to have a modest funeral instead of a lavish one, without a rigidly prescribed period of mourning. The three years that a child is completely dependent on their parents is demonstrated by having a coffin three inches thick and three layers of clothes on the deceased. Instead of extended mourning periods, Mozi states that a filial child should cry at the funeral and make sacrificial offerings their parents. “There should be crying as one sees the departed off and as one comes back from the grave. But as soon as people have returned to their homes, they should resume their individual livelihoods. There should be regular sacrificial offerings made to extend filiality to one’s parents.”13

Conclusion:

I agree with Mozi that modest funerals and sacrificial offerings are tasks of a filial child rather than lavish funerals and prolonged mourning. Mozi takes a more logical approach to filial piety, while Confucius’ approach is more emotional. Even though grief is originated from commitment to family, what good is experiencing emotions if it brings no benefit? While the three year mourning period represents the respect and attachment that a child has for their parents, the reality is that it brings starvation, weakness, and less work. Starvation and weakness leads to increased deaths, and less work leads a poorer and disorderly economy. Therefore, the three year mourning period does not bring any benefit to one’s parents and it brings harm to society. I believe that one should be able to express sadness after their parent’s death, but their grief should not be causing harm to society. “Burying, mourning, and sacrificing to the dead should be done in moderation and should not waste social resources or cause delays for the matters of the living.”14 If grief and mourning periods are causing harm to society, it is unclear how they could be classified as the obligations of a filial child. One can’t be obligated to cause unnecessary, avoidable harms to oneself or others. And, taken stringently, the Confucian mourning requirements might reasonably be thought to entail such harms. As such, one might argue that Confucius’ ideas of a three year morning period and lavish funerals are not tasks of a filial child because they do not benefit their parents or society.

In contrast, Mozi’s proposal of modest funerals and sacrificial offerings are a reasonable approach to show filial piety to one’s parents. Modest funerals honor one’s parents through being intentional about three layers of clothes on the deceased and making the coffin three inches thick to symbolize the three dependent years. The small details still spark a connection of respect between a child and their parents. Through modest funerals, children are still able to show respect to their parents through the ritual of the funeral and giving offerings to honor their parents. Offerings at a funeral represent precious objects that are given up by a filial child to show how much their parents mean to them. On the day of the funeral, children are able to express grief that shows a commitment to their parents and engage in a rite of mourning. And a filial child may, of course, continue grieving after the funeral. However, grieving does not need to suspend one’s life as fully as Confucius seems to argue. By resuming their lives, children are able to bring order and do their work to contribute to society, while continuing to process and work through their loss. What’s more, we shouldn’t assume all persons need to grieve in the same way; there may be distinct ways through which grief might manifest. While avoiding unhealthy patterns of grieving is important, it’s not the case that there’s necessarily only one healthy form grief might take. Confucius would owe us a substantially stronger argument if that’s what he has in mind. Grieving children may also be able to study hard and make money to improve their families reputation when they resume their lives. This is an example of a filial child: one that experiences grief, but is still able to benefit their family at the same time. Parents are respected when their child produces actions that benefit the society. Therefore, I believe that a filial piety is maintained in children when they resume their life after the funeral, in order to benefit their parents by enriching their family and contributing to society.

- Bedford, Olwen, and Kuang-Hui Yeh. “The History and the Future of the Psychology of Filial Piety: Chinese Norms to Contextualized Personality Construct.” Frontiers in Psychology 10 (January 30, 2019): 100. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00100: 2. ↵

- Ivanhoe, Philip J., and Bryan William Van Norden. Readings in Classical Chinese Philosophy. 2nd ed. Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publ., 2005: p. 51. ↵

- Ivanhoe, Philip J. “Filial Piety as a Virtue.” In Working Virtue: Virtue Ethics and Contemporary Moral Problems, edited by Rebecca L. Walker and Philip J. Ivanhoe, 297–312. Oxford University Press, 2007: 307. ↵

- Ivanhoe & Van Norden, 2005: 50. ↵

- Radice, Thomas. “Confucius and Filial Piety.” In A Concise Companion to Confucius, edited by Paul R. Goldin. John Wiley & Sons, 2017: 188. ↵

- Qiyong, Guo. “‘Filial Piety,’ ‘Three Years Mourning,’ and ‘Love’: Differences in Positions and Debate Between the Confucians and Mohists.” Contemporary Chinese Thought 42, no. 4 (2011): 12–38. https://doi.org/10.2753/csp1097-1467420401: 21. ↵

- Qiyong, Guo. “‘Filial Piety,’ ‘Three Years Mourning,’ and ‘Love’: Differences in Positions and Debate Between the Confucians and Mohists.” Contemporary Chinese Thought 42, no. 4 (2011): 12–38. https://doi.org/10.2753/csp1097-1467420401: 17. ↵

- Ivanhoe & Van Norden, 2005: 80. ↵

- Ivanhoe & Van Norden, 2005: 82. ↵

- Ivanhoe & Van Norden, 2005: 83. ↵

- Ivanhoe & Van Norden, 2005: 83. ↵

- Ivanhoe & Van Norden, 2005: 84. ↵

- Ivanhoe & Van Norden, 2005: 89. ↵

- Qiyong, Guo. “‘Filial Piety,’ ‘Three Years Mourning,’ and ‘Love’: Differences in Positions and Debate Between the Confucians and Mohists.” Contemporary Chinese Thought 42, no. 4 (2011): 12–38. https://doi.org/10.2753/csp1097-1467420401: 31. ↵