In a time of Phyllis Schlaflys, Anita Bryants, and rhetoric that depicted homosexuality as a crime, going from being a careful and closeted man to California’s first openly-gay elected public official seems like a leap, but it was a leap Harvey Milk made. Despite knowing who he was at a young age, Harvey kept his sexuality to himself and lived a quiet life working as a teacher, an insurance and finance agent, and even as a discharged navy man until the early 1970s when he decided to pack up his life in New York and move with his boyfriend to America’s “Gay Mecca,” San Francisco, where he opened a camera shop on Castro Street.1 Milk quickly saw the need for reform all around the district, and without meaning to, became an important community figure, eventually becoming known as the “Mayor of Castro Street.” After starting an alliance with labor unions for boycotting Coors Beer Co., Harvey was thrown in the political arena and was soon being revered around the district as a leader for all types of interest groups. Despite the amount of support Milk had within his own district, he lost two elections for the Board of Supervisors and one for State Assembly. But by the fall of 1977, there would be a large shift in politics that would lead to Milk’s success.

While Harvey lost his third election, California’s Proposition T had won, and it would be instrumental in Harvey’s next campaign. Proposition T changed San Francisco’s election system from at-large elections, where officials are elected by whole cities to represent the entire city, to district elections, where officials are elected by sections of the city—districts—to represent that part of the city. The passage of Proposition T meant that all Harvey had to do to earn a seat on the Board of Supervisors was win in the Castro Street district, which Milk had virtually already done. In November 1977, Harvey in fact won his district’s seat for the San Francisco Board of Supervisors and became one of the first openly-gay public officials in America.2 Immediately, Milk hit the ground running with a quiet focus on the gay rights movement in California, which was being threatened by opposing movements, particularly Anita Bryant’s “Save Our Children” campaign, which gave birth to a plethora of other bigoted proposals and crusades. The counter-movements perpetuated gay stereotypes: it incited violence against gays and instilled fear of the gay community. It used these tactics to persuade people—especially conservative, religious people—to help prevent any legislation or ordinances in support of the gay community.3 However, Harvey, being the optimist that he was, saw this as an opportunity. Anita Bryant and the band of religious conservatives would be the catalyst for what would become Harvey’s greatest contribution as a Supervisor.

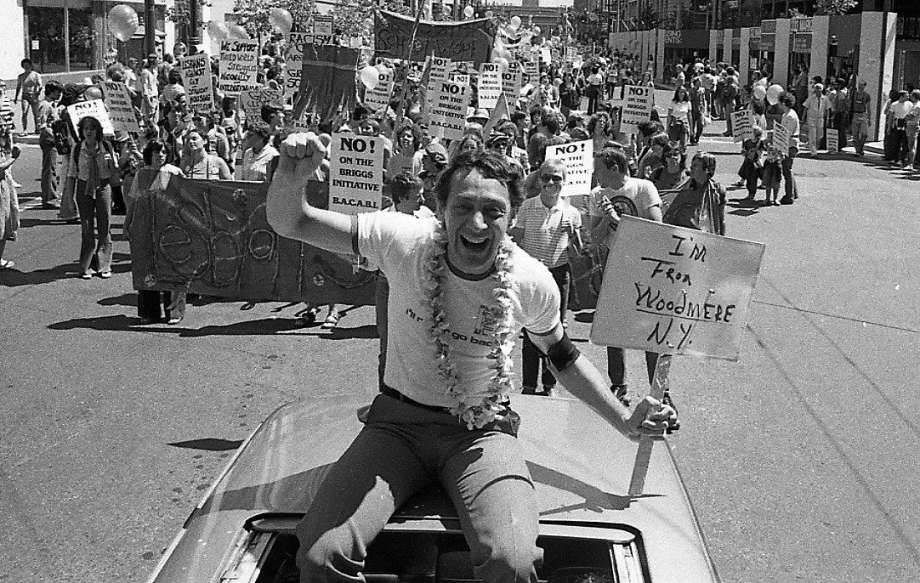

By the time Harvey was sworn in on January 8, 1978, the Brigg’s Initiative, or Proposition 6, was getting ready to change California by jeopardizing the lives of men and women all across the state. The purpose of the Brigg’s Initiative, named after the conservative state legislator and Anita Bryant’s newest recruit, John Briggs, was to target gay men and women from working in any California public school district. The initiative was fully equipped with a clause that provided instructions on how to identify and prove that the accused was gay. Had Proposition 6 been introduced to the Castro Street district alone, it would have been quickly shot down. However, the fight didn’t just threaten Milk’s district. Harvey needed the support of the entire state of California to come out and stand against the Brigg’s Initiative in order to save the livelihood, privacy, and lives of the thousands of people that would be affected if the initiative were to pass. Cleve Jones recalls Milk saying, “Even if we lose, having the debate moves us forward, just by making people think about the issue….And we have to get everyone to come out of their closets.”4 This proved to be a long and painstaking process.

The months leading up to November 7, 1978, election day for the Brigg’s Initiative, came in loud and hectic waves. The battle against Briggs, Bryant, and a few other Board members would prove to be tough, but Harvey had started his career as Supervisor Milk with some successes. Harvey’s popularity and openness about who he was proved to be a key tool when building relationships within the board and with the public. Milk was able to connect to his constituents and gain their trust on a completely frank and human basis by acting on his politics and keeping his promises.5 And because the Board of Supervisors finally reflected the diversity of the district, Harvey found it easy to create relationships and alliances with other newly elected Supervisors: Ella Hill Hutch, an African-American woman, Gordon Lau, a Chinese-American activist, Carol Ruth Silver, a single mother, and liberal Mayor George Moscone.6 Needless to say, Harvey thrived within the Board, and was able to gain the support of all of his fellow board members, except for one: Dan White. Dan White was the anti-Harvey. And although he had no personal connection to Anita Bryant, he ran on a campaign that was founded on similar promises. However, despite often bumping heads with White, Harvey was able to enact the two most important ordinances of his short career: the Pooper Scooper Ordinance, which tackled San Francisco’s most talked about issue, dog poop, and which forced pet owners to clean up after their pets; and the Gay Rights Ordinance, which protected gay men and women from discrimination in housing, employment, and other public spaces, which passed with only one dissenting voter, Supervisor Dan White.

But while Harvey was working to have his ordinances passed, he had to continue fighting against his opponents on the other side of the battle. Anita Bryant went on tour and launched successful attacks against gay ordinances in St. Paul, Minnesota, Wichita, Kansas, and Eugene, Oregon, all within the time span of a month. Harvey saw a chance to capitalize on the outrage caused by the Counter-movement’s successes and stir up conversation. For every ordinance Bryant had killed, Harvey and other activists organized three-mile marches that ran from Castro Street to Union Square in response—each one with participation larger than the last. Such public acts of discontent started conversations and made people aware of the bigotry of the Counter-movement and of the injustices of Proposition 6.

The Briggs Initiative was clearly ahead in votes through Gay Freedom Day and the rest of that summer, but by the end of September, the campaign against Proposition 6 had become the largest political movement for the gay community to date, and by October 11, Harvey had come close to closing the gap on the votes he needed to stop the Initiative.7

That October 11, Supervisor Harvey Milk and Professor Sally Gearhart, an openly gay women’s studies professor, in a televised debate parleyed the Briggs Initiative with state legislator John Briggs himself. The consensus of those who watched the debate named a clear winning team and a clear loser. After the debate, the gap between voters for and against the initiative dramatically narrowed, and people and newspapers began openly condemning the Proposition. All of this would seem reassuring; however, Harvey still feared for the worst. More than anything, Harvey wanted to prevent riots from breaking out if the Proposition passed. The three-mile march strategy was created to tire marchers and prevent riots from breaking out. But despite closing the gap, the Initiative still had a chance of passing. If the Briggs Initiative were to survive after all they had thrown at it, there would be no stopping the riots that were already being talked about in the streets. Then the final nail in the Briggs Initiative coffin hit. On November 1, six days before the vote, Ronald Reagan announced his lack of support for Proposition 6.8

The six days after Reagan’s announcement, every anti-Proposition 6 organization went into overdrive. More rallies were held, more volunteers handed out pamphlets and went knocking on doors. And then the day came. On November 7, 1978, Proposition 6, the Briggs Initiative, was voted down: 58.4 percent of California voters voting against, and 41.6% of voters voting for.9 The numbers were impressive; no riots took place, and the thousands of homosexual citizens in California were saved.

Three days after the Briggs Initiative was shot down, Milk got another surprise. Supervisor Dan White was stepping down due to the little pay he received serving on the Board. Not to say that Harvey didn’t like White, but despite efforts made to create a friendly relationship with White, the two could never get along, and White’s resignation pleased Harvey. White’s departure meant that Mayor Moscone could change the composition of the Board to a liberal majority, and Harvey was ready to recommend a successor. However, four days after White resigned, he asked for the position back. Once Harvey caught wind of the news, learned that Moscone was considering it, Harvey was affronted. Milk immediately confronted Mayor Moscone and persuaded him not to reappoint White, and he didn’t. This maneuver was experienced as a huge slap in the face to Dan White, who already had a problem with Milk, and it made him all the more infuriated.

On November 27, 1978, former Supervisor Dan White snuck into San Francisco City Hall through a basement window to avoid being checked, and walked to Mayor Moscone’s office to ask him one more time to reappoint him to the Board. The two began to argue, and the two moved into a private room where Dan White took out his gun and shot Mayor Moscone multiple times and killed him. White then burst into Harvey Milk’s office, and shot Harvey to death. After serving on the Board of Supervisors for only eleven months, Harvey Milk was assassinated.10 The heartache ran deep all over California. Marches were held in remembrance, but soon the heartache turned to anger and the riots following the trial of Dan White would come to be known as the “White Night Riots.” Dan White’s trail publicly exposed the dynamics of homophobia in America after White was convicted of manslaughter, insinuating he unintentionally committed murder, as opposed to first-degree murder, which would imply that White planned and intended to kill Milk and Moscone.11 Dan White’s attorney contended that the amount of junk food that White had been eating prior to the murders made him oblivious to what he was doing—later called the “twinkie defense”—and the jury ran with it.12 White was sentenced to seven years in prison, was released on probation after five, and committed suicide on October 21, 1985, a few weeks after he was released.13

Despite Harvey’s tragic end, ever since he started his first campaign, he felt as though things would end this way. He recorded three tapes to be played in the event of his assassination, talking about the gay rights movement, the counter-movement, his succession, and his intentions. Without a doubt, the tapes symbolize his selflessness and willingness to accept the chance of assassination for the sake of the gay community and for the sake of giving people the opportunity to open up about who they are without fear. Harvey Milk will continue to be remembered as one of the most inspiring leaders in American history and a model politician, but Harvey’s character and cause could best be described with a quote from one of these tapes, “If a bullet should enter my brain, let that bullet destroy every closet door.”14

- Encyclopedia of Activism and Social Justice, 2007, s.v. “Milk, Harvey (1930-1978),” by Gary L. Anderson and Kathryn G. Herr. ↵

- Funk & Wagnalls New World Encyclopedia, 2017, s.v. “Harvey (Bernard) Milk.” ↵

- Salem Press Encyclopedia, 2015, s.v. “Anita Bryant Campaigns Against Gay and Lesbian Rights,” by Jesse B. Powell. ↵

- Cleve Jones, When We Rise (New York: Hachette Books, 2016), 135. ↵

- Charles E. Morris III, Queering Public Address (South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press, 2007), 82-83. ↵

- Cleve Jones, When We Rise (New York: Hachette Books, 2016), 139. ↵

- Cleve Jones, When We Rise (New York: Hachette Books, 2016), 156-157. ↵

- Cleve Jones, When We Rise (New York: Hachette Books, 2016), 157-158. ↵

- Cleve Jones, When We Rise (New York: Hachette Books, 2016), 158. ↵

- Encyclopedia of Activism and Social Justice, 2007, s.v. “Milk, Harvey (1930-1978),” by Gary L. Anderson and Kathryn G. Herr. ↵

- Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia, February 2017, s.v. “Harvey Milk,” by Robert B. Ridlinger. ↵

- Encyclopedia of Activism and Social Justice, 2007, s.v. “Milk, Harvey (1930-1978),” by Gary L. Anderson and Kathryn G. Herr. ↵

- Funk & Wagnalls New World Encyclopedia, 2017, s.v. “Harvey (Bernard) Milk.” ↵

- Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia, February 2017, s.v. “Harvey Milk,” by Robert B. Ridlinger. ↵

79 comments

Alexis Martinez

This article did a great job of highlighting Harvey’s life, accomplishments, and the trouble he faced as an LGBT member. Before this article I had little to no knowledge of Harvey Milk’s life but after reading this I truly think he was inspiration to other LGBT members. It’s a shame that he died so soon, but he died fighting for what he believed in which makes him even more of an inspiration.

Gabriela Ochoa

I never knew of Harvey Milk until I read this article. Its interesting that he moves to California and automatically people want him to hold a seat and that at a time like that people would be so supportive of him and his campaign. I like that the author provided a background on what the propositions meant an what they stood for. I was happy to read that he was able to hold a spot but was sad to see his life ended by a man who just didn’t like him. I feel that he could hate made more of a difference in the world in this community.

Natalie Juarez

This article was very descriptive to which allowed me to create a visual and personal image of how Harvey Milk’s advocacy impacted the LGBT+ movement. His sacrifice to end homophobia and his life work contributions to making LGBT+ people feel seen and heard are admirable and inspiring. I love how this article included the diversity of newly elected Supervisors who supported Milk to show that he was a personable human being in that people could resonate with him and his fight. I knew that Milk had gotten murdered, but I did not know that his murderer, Dan White, was later on released due to the “twinkie defense.” This information is disheartening but it is a prime example of how homophobia is often overlooked, which is terrifying.

Devin Ramos

I never knew about Harvey Milk until I came across the movie on Netflix my senior year of high school, and this kind of made me mad that we weren’t taught about a influential character in the LGBTQ movement. Harvey Milk took a brave chance on running for office multiple times him being a openly gay man gave people in the closet hope, and I saw this in the youtube video at the end about how someone called him and said thank you. It is a shame that homophobia was the reason he was murdered but the revolts and the walks and the movements that were created due to his assassination.

John Smith

It’s a shame that Milk had died a martyr, but sadly that was what probably united the gay community in California (and maybe that’s why there’s such a strong LGBT community present in California now). It’s great that California had such revolutionary politician for it’s time. Everybody deserves freedom in their sexuality, especially in a country like America.

Julio Morales

I had never heard of Harvey Milk but from reading this article I can see that he was a selfless individual who died for his beliefs. He obviously knew that death was a possibility and that is why he made those videos in case he was murdered. It’s really impressive that in 11 months he was able to put down a proposition that threatened the personal lives of many gay individuals.

Fumei Pinger

I’ve come across this article a few times, and today I finally clicked on it. I was wowed. I liked how the author tied everything together. It started with the public opinion of how society viewed gays and tied Harvey Milk into the big picture of the gay rights movement. Every detail in this story had meaning, from the description of the Castro district in San Francisco to that board president, Dan White, who never liked Harvey. My interest was piqued when the author mentioned the “Twinkie Defense” because I’ve heard of that before but had no idea that this was the event that set the precedent. This story was very well done.

Constancia Tijerina

This article provided me with some more information that I have not heard of by Milk and I think that is a strong point towards how descriptive this article is. Even though I had prior knowledge of the accomplishments of Milk, but I have not gone into depth of the impact towards the people and how every reaction mattered for the next action Milk would make. As an individual who is part of this community, I have a strong opinion of how there was no justice served. However, even after his death, there was a strong statement being made that there should be justice made against harassment towards the LGBT community. Such a great article, I had to comment twice!

Irene Astran

I appreciate this article on such a deep level. We need to uplift people of the LGBT community to feel safe in pursuing a seat at the table or a seat in office. I intend to share this article with St. Mary’s LGBT organization, Safe Space. I hope they are as inspired by the story and the video as I am.

Angelica Padilla

I really enjoyed reading this article and seeing the growth of Harvey Milk as a politician. It is not only inspiring but also shows the amount of bravery Milk had, knowing he would face assassination if it meant speaking about something he stood for. No matter how many times Milk lost an election, he still continued on not letting his failures get in the way until he finally made it.