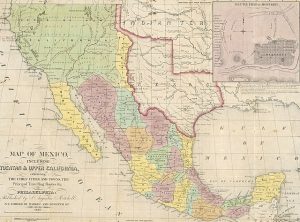

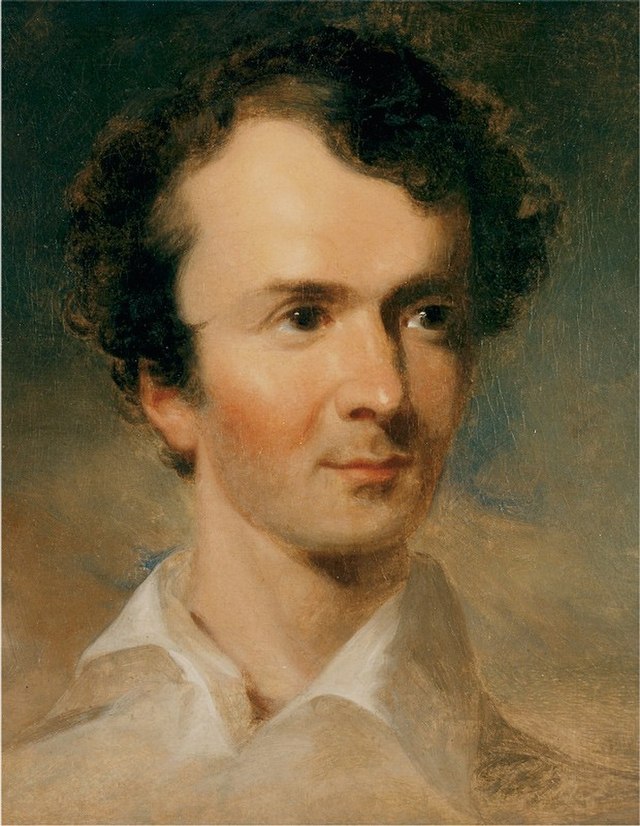

Nicholas Trist, a Virginian and a diplomat, had strong ideals, even if they made him question his superiors. After a year of success on the battlefield against Mexico, the Polk administration considered it the proper time to establish peace negotiations with Mexico. The Polk administration would need to choose a representative for the negotiations. Nevertheless, the Polk administration struggled to find the correct person for the duty. Several of the obstacles that the Polk administration faced during the selection process was that if they chose someone from the Democrat party, it would generate jealousy among the party for the presidential nomination. The idea of selecting someone from the opposing party was clearly off the table, and Secretary of State James Buchannan could not leave his job. In the spring of 1847, Secretary of State James Buchannan suggested Nicholas P. Trust, chief clerk of the State Department, as a candidate for the job. Trist was the best candidate for the job as he had learned to speak Spanish when he had served as U.S. consul in Cuba, and he was faithful to the Democrat party.1 The suggestion of Trist as the representative in Mexico then received approval from Polk’s cabinet and Secretary of State James Buchannan. Trist received all the power in the treaty project and had the instruction to establish the Rio Grande as the southern border and have Mexico cede all upper California and New Mexico territory to the U.S. Additionally, Trist would also be instructed to keep his mission undercover and proceed on his trip to Veracruz, which had come under the control of General Winfield Scott.

Trist began his trip to Mexico, but stopped in New Orleans before finally arriving in Veracruz. Polk’s administration would explain the abrupt journey of Trist as a family emergency to see his youngest sibling Browse, who supposedly was ill. On his way to Louisiana, Trist traveled incognito by mail coach and steamer. Unfortunately for Trist, his trip was exposed, and his mission would no longer remain in secrecy. During his stay in New Orleans, Trist disguised himself as a French merchant to remain unnoticed by the American public.2 Trist then arrived in Veracruz, but before situating himself at the U.S army headquarters in Jalapa, Trist brought a letter to General Winfried Scott that was from President Polk and Secretary of State James Buchannan instructing him to cease military action. Scott was upset with the letter; he considered that all military action should only be a military matter, and it was his responsibility to protect his men in hostile territory.3 Scott disobeyed the orders of President Polk and Secretary Buchannan, and only followed such orders if Trist held a military rank above him. Trist then sent letters to Secretary Buchannan complaining about General Scott’s actions, and the conditions of the American soldiers there. The discord between Trist and General Scott continued; Trist explained to General Scott that those orders were not instructed by him but by President Polk, the commander-in-chief. President Polk was frustrated with the discord between Trist and General Scott; at some point, President Polk considered recalling Trist and General Scott, but Polk’s cabinet convinced him that that would be a bad policy. Trist sent letters to Washington stating that his relationship with General Scott was improving, and in recent times there had not been any confrontations between them.4. Eventually, the relationship between Trist and General Scott came to good terms, and Trist started to be well-received in Scott’s camp.

Trist tried to contact Mexican officials and even President Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna through third parties. Santa Anna successfully received messages from Trist but did not respond to them. Nevertheless, Santa Anna sent a letter to the Mexican congress stating that any proposition of peace from the United States should be considered. The Mexican congress decided to ignore Santa Anna’s message, but Santa Anna decided to take action into his own hands and started the negotiating process. Trist faced the first setback in the negotiations; Trist presented an offer in which the boundary between the two countries would be the Rio Grande river, and Mexico would have to cede Upper California and New Mexico plus a significant amount of money. Santa Anna rejected Trist’s offer and presented a counteroffer that proposed the Nueces river as the boundary between both nations, and would only cede upper California plus a considerable amount of money5 Trist knew that President Polk would reject such a proposal, but still decided to send it to Washington so that Santa Anna and the Mexican officials could see the goodwill of the U.S. government. On September 14, 1847, General Winfield Scott and his men took possession of Mexico City.6

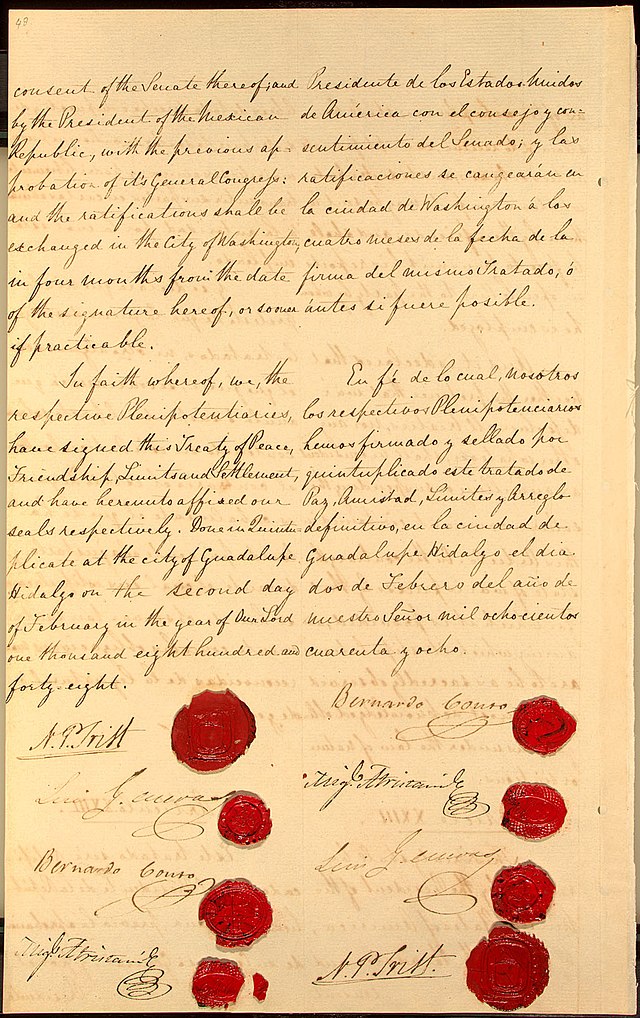

Two days after the taking of Mexico City, General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna resigned. Manuel De La Peña, former head of the supreme court, took over the Mexican presidency. De La Peña appointed Luis de la Rosa as Minister of External Relations. As both parties accomplished significant advancements, the negotiations then suffered another setback, as the De La Peña presidency only lasted one month. Under the new administration, De La Peña became the foreign relations minister and reestablished negotiations with Trist. President Polk became impatient as the pressure in Washington started to rise, and support for the war became unfavorable. Polk considered recalling Trist.7 Trist informed De La Peña and the other Mexican officials about Polk’s orders regarding his recall. Trist was about to leave Mexico and return to Washington, but on December 4, 1847, Trist received a visit from James L. Freaner, a friend and correspondent of the New Orleans Delta. Freaner persuaded Trist to ignore the recall order and simply continue with his mission to reach a successful peace treaty.8 Trist also consulted General Scott about his decision to disobey the recall orders. After consulting Scott, Trist informed De La Peña and the Mexican representatives about his decision to ignore the recall order and continue with the negotiations, a decision that could cost him. Trist established the terms of the negotiations by making it clear to De La Peña that he would only sign the treaty if the original project of the United States was satisfied, and he would not consider any counter-proposals or arguments. The Mexican commissioners and Trist met on December 28, 1847; these negotiations took place in Guadalupe Hidalgo. After an entire month of disputes and discussions, Trist successfully obtained an agreement with Mexican commissioners that met the conditions of the U.S. proposal. The agreement established that Mexico had to cede the territories of New Mexico and upper California. The deal would also set the boundaries between both nations in which Mexico would recognize the Rio Grande river as its main boundary with the United States. On February 2, 1848, Trist met with the Mexican commissioners to sign the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo. Trist would be the only U.S. representative there to sign the treaty.

After successfully signing the treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo, Trist sent the Treaty to Washington. Polk received the treaty but was displeased with Trist’s decision, causing him and his cabinet to doubt whether they should accept the treaty. Even though Polk was unhappy with Trist, Polk had no other choice than to take the treaty and send it to the Senate. The Senate committee on Foreign Relations rejected the treaty because Trist was officially no longer a representative of the U.S. After two weeks of debates in the Senate, on March 10, the treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo was passed with the voting of 38-14 in favor of the treaty.9

Trist returned to Washington with the expectation of being rewarded for delivering a peace treaty with Mexico and for serving the country. Unfortunately for Trist, that would not be the case, as President Polk immediately fired him. Trist’s political career was over, and he subsequently moved with his family to Westchester, Pennsylvania, where he suffered severe economic struggles. In 1851, Trist and his family moved to New York, where he began to work in a law firm. The financial status would slightly improve for Trist and his family. Trist once again suffered a setback in his life as his job in New York would end, and he eventually would return to Philadelphia with his family. In Philadelphia, Trist’s wife, Virginia Jefferson Randolph, Granddaughter of President Thomas Jefferson, would open a school for women. Trist’s wife’s academy suffered from poor income, leading Trist to work on different projects; however, none were fruitful. For many years Trist’s financial situation would continue without improving, and his health began to deteriorate. The years passed, and Trist still did not receive his compensation for delivering the treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo, the administrations after Polk would continue to ignore his case and achievement. In 1870, after twenty-two years of signing the Guadalupe-Hidalgo treaty, Trist was finally compensated and would enjoy compensation for the rest of his last days.

- Wallace Ohrt, Defiant Peacemaker: Nicholas Trist in the Mexican War, 1st ed, Elma Dill Russell Spencer Series in the West and Southwest, no. 17 (College Station, Tex: Texas A&M University Press, 1997), 102-103. ↵

- Graebner, Norman A. “Party Politics and the Trist Mission.” The Journal of Southern History 19, no. 2 (1953): 145. ↵

- Jack Nortrup, “Nicholas Trist’s Mission to Mexico: A Reinterpretation,” The Southwestern Historical Quarterly 71, no. 3 (1968): 326-27. ↵

- Jesse S. Reeves, “The Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo,” The American Historical Review 10, no. 2 (1905): 316–17 ↵

- Amy S. Greenberg, “NICHOLAS TRIST.,” in Embajadores de Estados Unidos En México, ed. Roberta Lajous, Diplomacia de Crisis y Oportunidades (El Colegio de Mexico, 2021), 55. ↵

- Robert A. Brent, “Nicholas P. Trist and the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo,” The Southwestern Historical Quarterly 57, no. 4 (1954): 463. ↵

- Louis Martin Sears, “Nicholas P. Trist, A Diplomat with Ideals,” The Mississippi Valley Historical Review 11, no. 1 (1924): 95. ↵

- Thomas J. Farnham, “Nicholas Trist & James Freaner and the Mission to Mexico,” Arizona and the West 11, no. 3 (1969): 247. ↵

- Patrick J. Buchanan, “Jimmy Polk’s War,” The National Interest, no. 56 (1999): 103–105. ↵

1 comment

Isabella Lopez

I learned about the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in high school but I don’t remember Trist’s name being mentioned or made significant when taught to me. That’s sad that he was treated that way, especially the part about financial struggles because lack of compensation.