What is the solution to combating law enforcement agencies who operate as terrorists? 18 United States Code section 2331(5) defines “domestic terrorism” as follows: “activities that— (A) involve acts dangerous to human life that are a violation of the criminal laws of the United States or of any State; (B) appear to be intended— (i) to intimidate or coerce a civilian population; (ii) to influence the policy of a government by intimidation or coercion; or (iii) to affect the conduct of a government by mass destruction, assassination, or kidnapping; and (C) occur primarily within the territorial jurisdiction of the United States. . . ” The applicable portion of this codification is (B)(i), because law enforcement agencies perform acts that intimidate or coerce a civilian population — that being the black population. (A) and (C) are elements easily met by the commissions of murder and attempted murder.1

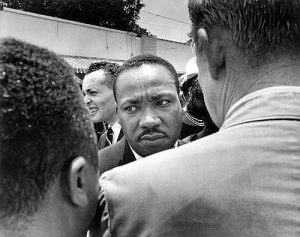

Currently, in the United States, police brutality is synonymous with violence against Blacks and Hispanics; these incidents are often captured on the electronic devices of the police officers constantly surrounding Black and Hispanic men, brutally assaulting them, and, in many cases, killing them. Even after pleading with the officers to stop, they continue beating the victims within an inch of their lives while laughing about it. Many of these cases go unsolved. In addition, in past and present history of police brutality incidents or murders, many of the law enforcement officers and the leadership belong to racist organizations such as the Ku Klux Klan and other racist hate groups. Throughout the history of this nation, these brutal murders occurred in places such as Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Tennessee, South Carolina, Florida, and North Carolina. These acts are dangerous to human life at a basic level, because they intimidate and coerce minority populations, and they are within the borders of the United States. These acts square directly within the definition of domestic terrorism.

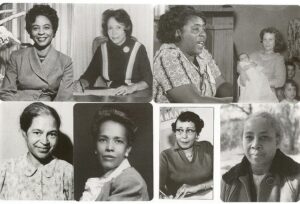

Courtesy of https://www.splcenter.org/what-we-do/civil-rights-memorial/civil-rights-martyrs

The police play a vital role in our community. It is law enforcement’s job to serve and protect the citizens in the community, deter crime, and bring criminals to justice. However, this authority has the means to achieve goals, which include the power to arrest, search, and use necessary force against those who break the law, and they are also enabled to undermine one’s civil rights. When law enforcement obstructs liberty in ways that go far beyond the bounds of what the law permits, they not only harm citizens without legal justification, but they also betray the trust that should exist between the government and a democratic society. The current issues that involve internal procedures are constantly compromised by the disciplinary measures handed down by senior law enforcement to the officers who commit serious infractions and to the arbitrators who commonly side with the officers and the chain of command during the hearings. From an accountability standpoint, this mindset can be problematic when arbitrators constantly reduce or overturn the termination or suspension of officers not fit to serve on the force. In many cases, these officers who are fired from the force still end up with jobs in law enforcement in smaller towns that support or turn a blind eye to such racist behavior.2 For illustration, former Cleveland police officer Timothy Loehmann, the officer who murdered Tamir Rice, was subsequently sworn into a law enforcement position in Tioga Borough, a small town in Pennsylvania, but immediately resigned his new position due to public scrutiny by the citizens in the community. According to Tamir Rice’s family attorney, the Tioga Police Department violated the law by not conducting a formal background check on Loehmann.3 This is a similar instance that is not new in the state of Louisiana. An example of this is Baton Rouge Police Chief Murphy Paul’s attempt to try to change the culture of the Baton Rouge Police Department.

Chaos erupts at metro council meeting as BRPD chief calls out councilmembers. Courtesy of WBRZ

FBI probes Baton Rouge police over torture allegations in ‘Brave Cave’. Courtesy of Scripps news

History of police brutality in the United States

The history of police brutality dates back to the days of slavery. The policing of Blacks and Hispanics began in the United States in the form of surveillance, occupation, and pacification. Before the establishment of police forces in cities at the end of the nineteenth century, many of those in power depended on the manipulation of the law. This was achieved through violence — terrorism to intimidate people of color. This type of warfare resulted in genocide and the containment of societies. This type of warfare also included the illegal annexation and occupation of land.4

An example of this is the case of Willa and Charles Bruce at the beginning of the twentieth century. The Bruce family purchased a long stretch of beachfront land in Manhattan, California, in 1912 for $1,225. A resort was built and would become known as Bruce Beach Resort. This would become a well-known leisure resort that blacks could visit that would provide them with rare beach access in California during a time when Jim Crow laws were still in effect. The Bruces would be terrorized by the Ku Klux Klan on a constant basis. The hate during this time was so intense that the KKK set the lower main deck on fire, forcing black visitors to walk adjacent to another rich property owner by the name of George Peck, who then outlined a no-trespassing rule on his property. When harassment did not work, the Manhattan city officials immediately condemned and seized the property owned by the Bruces, citing imminent domain for the need of a public park.5

This was a common tactic used to keep Blacks in line and prevent their progress. The main priority in the Deep South before the Civil War was “policing” and maintaining the institution of slavery. The individuals who were employed to oversee this mission were known as “patrollers,” and their primary purpose was to track down fugitive slaves and prevent slave revolts. The role of these patrollers would become the police force in the South. The type of violence and severe punishments associated with police brutality that exist in our nation today were not only part of the culture, but were codified into laws. In 1705, a law was passed in the colony of Virginia that allowed slave owners to mutilate Blacks as punishment for crimes of which they were accused. In 1723, the colony of Maryland passed a law that allowed the cutting off of ears of enslaved Blacks, thus reminding them of their place in society. When the United States Constitution was ratified in 1788, among other things, it guaranteed the use of federal military forces to put down any slave revolts. This was an assurance reinforced by the Fugitive Law of 1793.6

Post Civil War

At the close of the Civil War, it was believed that slavery was a thing of the past. Many Blacks counted on the state to protect them and provide a safe environment in which they could start building their lives as free people. At times, the Union troops, many of whom were Black, actually did protect the formerly enslaved people. However, before the rise of the Radical Reconstruction, many southern Blacks still fell into a harsh state of oppression and violence. After President Andrew Johnson was sworn into office, he handed power back to the Redeemers (former secessionists who were largely Democrats). Afterward came a vicious wave of terrorism sweeping throughout the South. On December 24, 1865, six ex-Confederate soldiers in Pulaski, Tennessee, formed the first terrorist organization in the United States. This group would become known as the Ku Klux Klan, and ex-Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest would take on the role of a grand wizard of this terrorist organization. The Ku Klux Klan’s sole mission was to destroy Blacks’ way of life through intimidation—burning down businesses, destroying food crops, and lynching—in order to keep Blacks in their place in society. The Klan was the para-military force for President Johnson’s (D) administration, and he protected them.7

The act of lynching is essential for understanding the history and character of police brutality in the United States from the 1860s to the twenty-first century because it reveals the sexual and gendered dimensions of maintaining order and disciplining Blacks and Hispanics. The Redeemers dominated many areas of government in the South, looked away, and contributed significantly to terrorism by passing “Black Codes,” or laws that restricted Blacks’ freedom of movement to progress and sustain themselves independently. Black Codes also included specific “apprenticeship laws” that bound ex-slave children to the plantations. An apprenticeship is nothing more than another term for slavery, another form of mass incarceration of Blacks. During the period of the Black Codes and especially after the end of Reconstruction in 1877, racial supremacy and informal modes of terrorist acts against Blacks became the most persuasive method of policing. In addition, several cities and counties created police forces during the last days of the era in which lynching was common. Lynching was also a common practice used throughout the colonial world, in nations such as South Africa and the Philippines; this type of brutality found its way outside of the United States. The defenders of this brutality describe lynching as a form of popular justice, and lynching in the United States was primarily aimed at Blacks.8

From backlash to progress set forth by Reconstruction.

During the last decade of the nineteenth century, although the Republicans controlled the House and refused to seat southern Democrats due to electoral fraud, Congress declined to act on proposals to investigate all allegations of Blacks’ exclusion from an Alabama senatorial election in 1894 or to enforce the provisions of section 2 of the Fourteenth Amendment, which provided the reduction in the House of the State’s delegation if the state discriminated in voting at the same time, and there were a series of proposals by the southern senators and representatives to repeal the Fifteenth Amendment outright. The Supreme Court also played a pivotal role in invalidating national efforts to ensure full citizenship for Blacks. The Court struck down and eviscerated various Federal protections of Blacks’ right to vote. For instance, United v. Cruikshank, 92 U.S. 542 (1875), the dismissing of indictments arising from the Colfax Massacre, in which a white mob killed a group of Black voters in Louisiana; United States v. Reese, 92 U.S. 214 (1875), striking down sections of the 1870 Enforcement Act as beyond Congressional power, upholding various state efforts to deny other aspects of citizenship to Blacks, most centrally, the right to separate juries. See Williams v. Mississippi, 170 U.S. 213 (1898). Finally, the Court was asked whether the blatant disenfranchisement of Blacks through the new Southern constitutions would survive the constitutional challenges under the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments.9

Although slavery was abolished in 1865 and the 14th Amendment was added to the United States Constitution to prevent violent terrorist acts against Blacks in America, the police today continue to kill Blacks nationwide and turn a blind eye to the gruesome criminal acts committed against them. The formerly enslaved people were not allowed to take their places as equal citizens in the United States because police were given the green light to brutalize and hunt them as wild beasts, slaughtered without mercy.10 They are rewarded with immunity and freedom from being held accountable for such heinous acts.

In addition, the Supreme Court revised Section 1983, an old Reconstruction law that was created to enforce the 14th Amendment; changing this law gave law enforcement the protection needed from a lawsuit. This is known as qualified immunity. Under this doctrine of qualified immunity, any individual victim of police brutality must show clear evidence that the officers violated “clearly established” law. In other words, a police officer cannot be sued for violating an individual’s constitutional rights unless a previous case is pointed to in the act. Due to the vagueness of excessive force standards, fact-dependent, qualified immunity makes it practically impossible to prosecute police officers for police brutality (terrorism). The 14th Amendment almost does not have the teeth to be effective. The outcome of the 1876 presidential election between Rutherford B. Hayes and Samuel J. Tilden that ultimately would end the Reconstruction period through the Wormley Agreement (The Compromise of 1877) would seal the fate of Blacks in America.11 The Reconstruction period fundamentally dictated who would control America.

End of Reconstruction

In 1877, with months of racial tension throughout the South, the Reconstruction period was set to officially end. However, before Reconstruction could be brought to a close, a covert deal was being created at the Wormley Hotel under the threat of destruction and ferocity due to the Election of 1876. On Monday night, February 26, 1877, eight politicians met in an unlikely alliance to see if an agreement could be made that would prevent the Democrats from blocking the election vote with tactics that would delay the election. The Republicans were Ohio members of Congress who were close to Hayes – Representatives James Garfield and Charles Foster, along with Senators Stanley Matthews and John Sherman. Representatives John Y. Brown and Henry Watterson of Kentucky joined Representative William M. Levy of Louisiana and Senator John B. Gordon of Georgia to represent the Democrats.12

With the inauguration just days away, an informally arranged meeting by members of Congress resolved the standoff between the Democrats and Republicans. The meeting took place at the luxurious Wormley Hotel in Washington D.C. This hotel was owned by James Wormley, one the most well-to-do black men in the city of Washington D.C. That night, they reached an agreement in the room of W. M. Evarts, who also served on the Election Commission, and would later go on to serve as Secretary of State in the Hayes Administration.13

This agreement would stand to be one of the most consequential political deals ever made, and would forever change the trajectory of American history for the worse.14

The Wormley Agreement (The Compromise of 1877) essentially stated that the Democrats would acknowledge Hayes as President, but only with the understanding that Republicans would meet certain conditions.15 The following six elements were the points of the compromise:

- All Union forces remaining in the South must be removed from all Confederate states.

- The southern states would have the right to “control their own affairs.” This vague point was interpreted as granting the South the right to deal with Blacks without any interference from the Federal government.

- At least one southern Democrat would be appointed to Hayes’s cabinet. (Senator David Key of Tennessee was appointed to the position of Postmaster General. On the surface, this was viewed as a minor position, but carried the largest number of patronage jobs.)

- Another transcontinental railroad would be built in the South running through Texas.

- Legislation must be passed to help industrialize the South and restore its economy following the Civil War and Reconstruction.

- Democrats would not employ the filibuster during the joint session of Congress and would acquiesce to the election of Rutherford B. Hayes.

Two days later it was officially announced that Hayes had won the election, and on March 4, 1877, he was sworn in.The Wormley Agreement had become a reality officially ending the Reconstruction period, with special conditions. The Hayes Administration agreed to remove all federal troops from three southern states, Louisiana, Florida, and South Carolina. In addition, these three states would be allowed to govern over their own legislative dealings. This agreement specified the details of the relations between Democrats and Republicans. President Hayes did not fully understand the horrific impact that this agreement would have on blacks in America for decades to come. With the Compromise in effect, it abandoned all active efforts to ensure equal rights for blacks in the South.16 All prospective gains that Blacks made were quickly reversed. All advances within the government that Blacks had were stripped from them and taken over by Whites with harsh vengeance.This new doctrine of racial supremacy evolved quickly with the help of politicians, merchants, and businessmen. This philosophy still underpins and drives our legal system today. The slave trade was reinvented through the manipulation of laws and constitutional amendments preventing the federal government from interfering with any human rights issues in the South. This came in the form of Jim Crow Laws. This is how the system worked. Black men were commonly arrested for petty offenses and convicted under the newly created systems of Black laws; this legislation was created by White racist southern Democrats, keeping Blacks on the plantation and farms.17 In addition, Blacks were not allowed to go to school to advance their position in life. The objective was to keep Blacks economically depressed, and to maintain the status quo.

Further, the Jim Crow caste system was created to prevent intimate relationships between White women and Black men, while condoning sexual abuse of Black women by White men. In addition, a main objective for separating Blacks from Whites was to prevent the formation of class consciousness, by reinforcing White racial superiority claims and by socializing White men through segregated social practices that constructed Black men as inferior. This process removed opportunities for Black men to build viable relationships across racial lines.18 This was only the beginning as a new two-headed monster would surface and become even more vicious.

Brown v. Board and the response of the Mississippi Sovereignty Commissions.

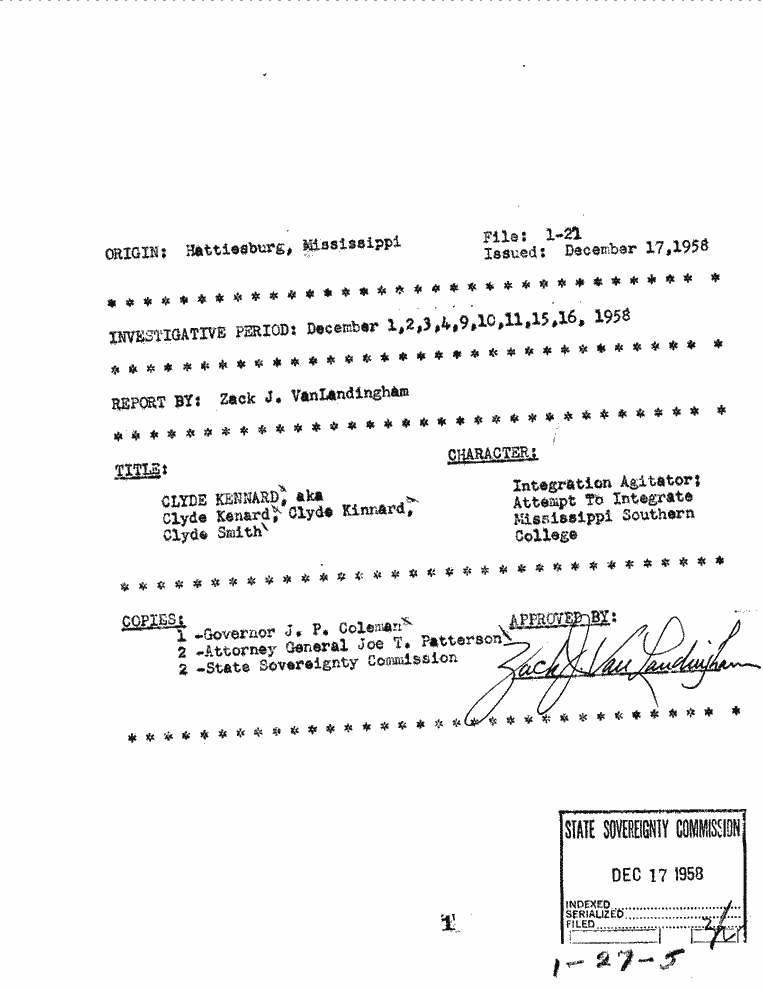

In the beginning stages of the Civil Rights movement, the Supreme Court handed down the Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka in May 1954. There, the Court ruled that laws enforcing segregating schools based on race were unconstitutional, and it called for the desegregation of schools immediately. This court ruling sent shock waves among those who believed in the separation of races, like many White southerners in the state of Mississippi.19 Mississippi’s response to this progressive decision was the creation of a new form of terrorism that was far more vicious than during Reconstruction. This new terrorist organization would be known as the Mississippi Sovereignty Commission. The Mississippi Sovereignty Commission was created and proposed through legislation by Governor James P. Coleman. The carefully drafted legislation that created the Commission had several proposals, one of which established this executive agency. The Commission was the result of a strategic plan to circumvent state and federal constitutional guarantees of due process and equal protection for the minority population; the agency worked for decades in the shadows to ensure that equality was not reached. In practice, the Commissions would surveil and deliver reports on Blacks and their daily activities to aforementioned actors. In this piece of legislation, neither the word segregation nor integration was ever mentioned in this legislation that created the Sovereignty Commission.20

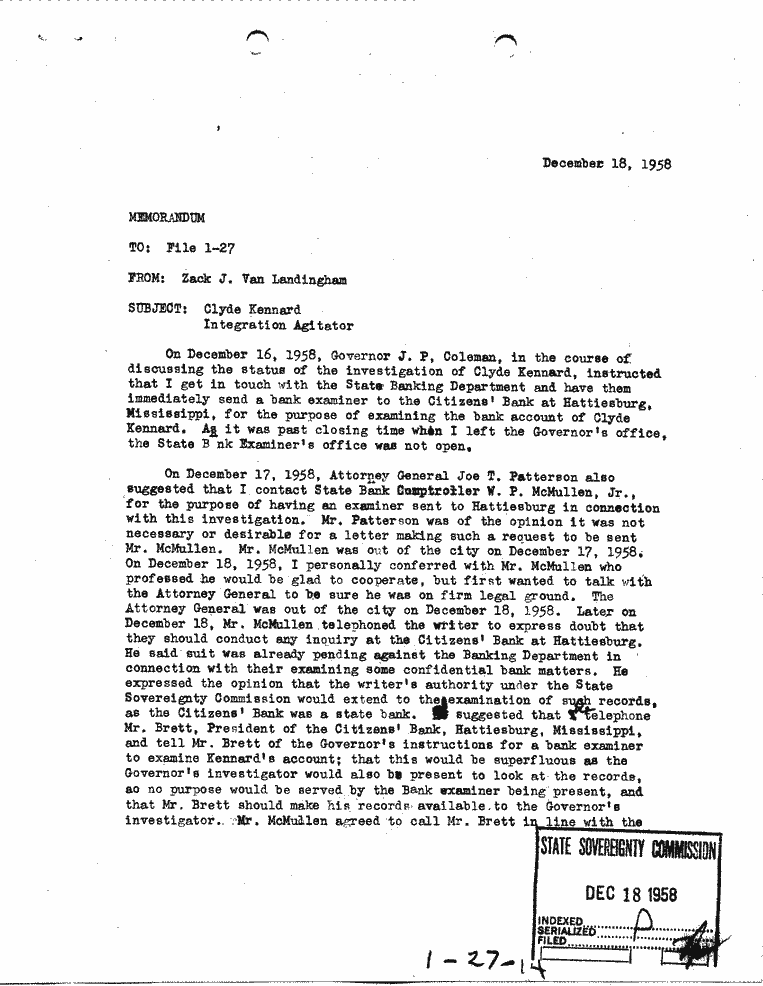

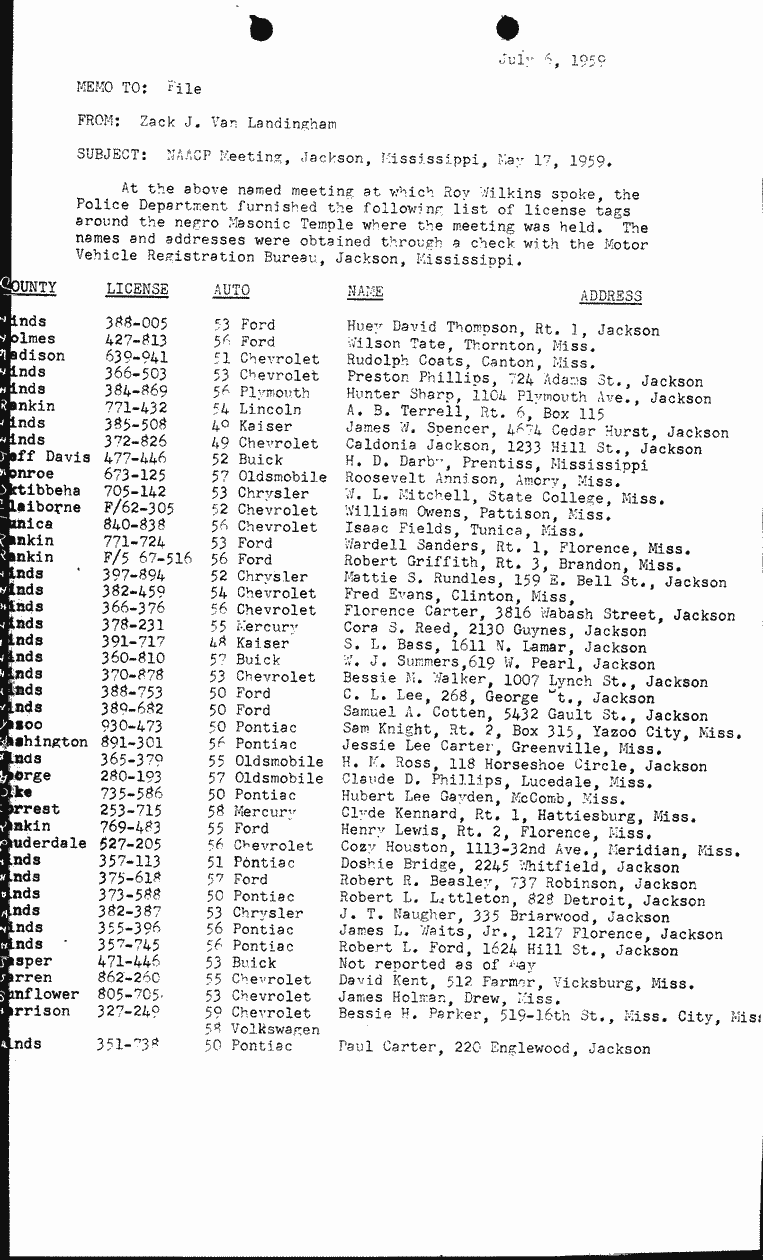

The Mississippi Sovereignty Commission had the authority to take any action necessary, such as issuing subpoenas and exercising police powers. The Commission worked very closely with the local White elected officials, the police, and the Ku Klux Klan hiding murders of Blacks. In practice, the Commissions would surveil and deliver reports on Blacks and their daily activities to aforementioned actors. Many who were suspected to be a part of the Civil Rights movement due to their participation in meetings were pressured with economic oppression, threats of dismissal from their place of employment, termination from their home rental agreement, and businesses subjected to being boycotted. The Mississippi Sovereignty Commission had the authority to take any action necessary such as issuing subpoenas and exercising police powers. The Commission worked very closely with the local white elected officials, the police, and the Ku Klux Klan. It also secretly funded the White Citizens Council. The Sovereignty Commission employed many of those who worked in law enforcement agencies. Amongst the first people employed by the Mississippi Sovereignty Commission were former FBI agent Zack Van Landingham, who created the Commission’s filing system once used by the FBI and also employed a Mississippi State highway patrolman.21 This parallel between the state-sponsored terror that was authorized by the Sovereignty Commission and the current brutal attacks by law enforcement officers against Blacks and Hispanics has created a path for White racists to infiltrate areas of local and state government. Notably, the Commissions also worked with locally paid Black informants to gain inside information, leveraging pressure against these individuals.

This was all to protect and enforce the racial status quo. The Mississippi Sovereignty Commission would also coordinate with its sister states Louisiana (Louisiana Sovereignty Commission) and Alabama (Alabama Sovereignty Commission). In later years it would be known as the Interstate Sovereignty Commission. Prior to this alliance, the Mississippi Sovereignty Commission reached out to other former-Confedearate states such Arkansas, Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia, and even Kentucky. Meetings were held in New Orleans, Louisiana in September of 1956. The Mississippi Sovereignty Commission sent representatives with the goal of organizing what would be known as the “Voice of the South” program. Of all of the states the Sovereignty Commission reached out to Georgia showed the most interest in the idea of the organizing of Southern States Publicity Men. In the end, the idea did not take form as Commission members had hoped.22 After the formation of the Interstate Sovverignty Commission, this terrorist organization became the watchdog racial segregation agency, and it worked with local and state police as well as local government politicians in the lynchings and murders of Blacks. In practice, the Commissions would surveil and deliver reports on blacks and their daily activities to aforementioned actors, with at least 87,000 names recorded as people of interest in Mississippi alone.23

The following individuals were victims of the Sovereignty Commissions:

Clyde Kennard

Clyde Kennard was a military veteran from Forrest County in Mississippi who served in World War II and the Korean War. He sought admission into Mississippi Southern College in 1955, 1958, and 1959. He was denied despite the landmark decision of Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, which made segregation in educational institutions illegal. The first time he was denied in 1955 was supposedly due to the fact that he did not have the required five letters of recommendation from his previous institution. In 1958, the school president and other administrative officers, as well as the governor, coerced him to withdraw his application, with the justification that the time for the integration of public learning institutions was not right. Substantiating the case that there was a conspiracy to keep him out of “white education,” the governor even offered, in 1958, to pay for Kennard’s tuition to a Black college. Afterward, the head of the Sovereignty Commission, a White racist and former FBI agent Zack Van Landingham, conspired to have a bomb planted on Kennard’s vehicle, or forced him to have a potentially fatal accident in his vehicle. In addition, Dudley Connor, a White lawyer from Hattiesburg, Mississippi, also an active racist, and member of the Hattiesburg Citizens’ Council collaborated with Van Landingham and told him that “if he desired for Kennard to leave Hattiesburg and never return, the Council leader could take care of him.” When Van Landingham asked Conner what he meant by “take care” of Kennard, Dudley replied that Kennard’s “vehicle could be hit by a train or he could have an accident and no one would ever know the difference.” Ultimately, this did not come to pass after they found another way to take him down. Kennard persisted in pursuing his education, and upon his third attempt for admission to Mississippi Southern College in 1959, he was denied on a technicality. These refusals for entry cannot be blamed on merit, as it was widely accepted that he was qualified for admission. Little did Kennard know, Governor Coleman and the University President McCain were plotting to neutralize him. They requested a meeting with him and handed him a formal letter of denial. As Kennard went to his car to leave, Forrest County Constable Lee Daniels and his partner suddenly arrested Kennard for having supposedly five bottles of alcohol under the back seat of his vehicle, and he was charged for excessive speeding. Kennard’s arrest was the result of racially motivated, coordinated efforts of resentment. As a result, Justice of the Peace T. C. Hobby fined Kennard $600, which was equivalent to three months’ salary. After this ordeal, the Sovereignty Commission had him framed and arrested for allegedly stealing a nominal amount of chicken feed. As Kennard continued to pursue his quest for admission into Mississippi Southern College, his aspiration was finally neutralized. On September 25, 1960, the Forrest County Cooperative, which had foreclosed on Kennard’s poultry farm, was burglarized, and five bags of chicken feed worth $25.00 were stolen from a warehouse. A nineteen-year-old Black youth, Johnny Lee Roberts, was arrested for the crime, but Roberts claimed that Kennard was the mastermind behind the alleged theft. By claiming this, Roberts “received a suspended sentence.” Kennard received a seven-year sentence in a Parchman prison, which was what the Commission wanted… to neutralize the threat to the racial status quo that Kennard posed. Medgar Evers issued a statement in regards to Kennard’s conviction stating that it was ” a mockery of the justice system.” Judge Hall cited Evers for contempt of court and fined him $100 and sentenced him to 30 days in jail. But the Mississippi Supreme Court overturned Evers’ conviction in 1961 and he served no jail time.[During his sentence, Kennard became ill with cancer and was pardoned by Governor Barnett. After Kennard’s release and his return to Chicago, he died two weeks later.24 This all lends support to the case that the Commissions, along with law enforcement, operated in concert to quell those standing up for racial justice. This coordinated effort constitutes domestic terrorism.

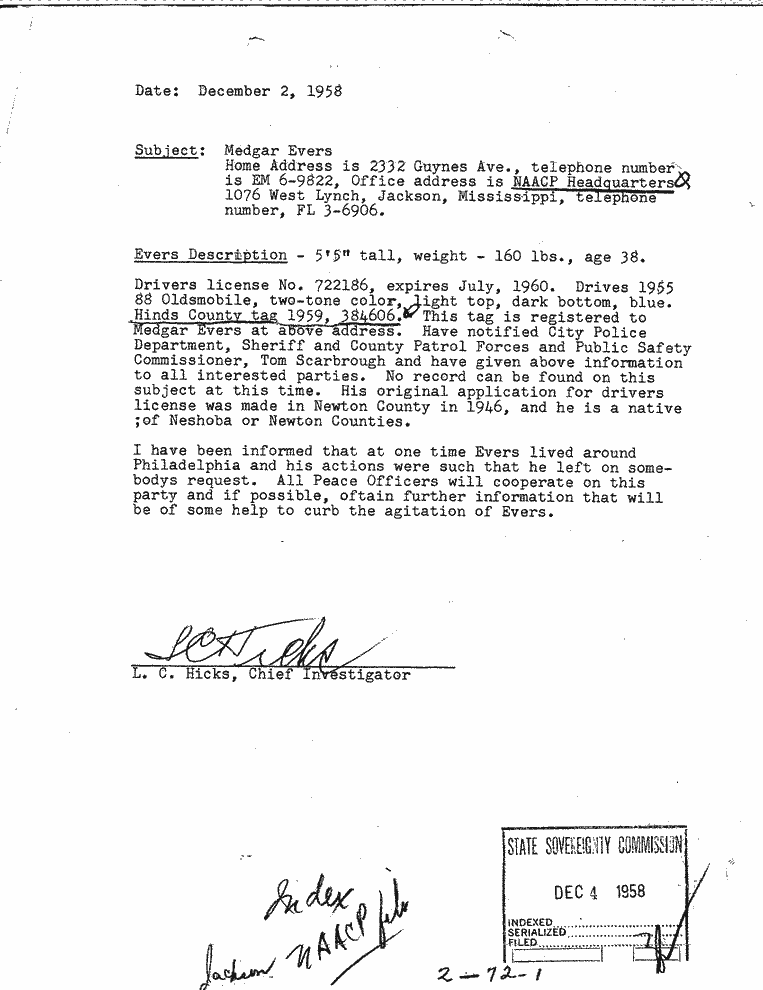

Medgar Evers

Medgar Evers was a military veteran, a Civil Rights activist, and the first Field Secretary of the NAACP in the state of Mississippi. Evers was also the President of the Regional Council of Negro Leadership that began to organize actions for civil rights. The leadership of Evers made him a target of the Mississippi Sovereignty Commission. Hal Decell, an editor and owner of a publishing company the “Deer Creek Piot,” had Medgar Evers followed to meetings throughout Mississippi and nearby Delta towns. Hal Decell, who won over the trust of Rev. H. Humes, was one of the first Black informants in the commission and was given the task to follow Evers and collect information for the Sovereignty Commission. It was also requested that information be obtained on all of the vehicles that were registered to Evers and other civil rights activists in the state. Decell, in a memorandum to the Commission, stated that once all of the information was collected, this information should be passed on to the Mississippi state troopers. This encouraged the troopers to harass those vehicles and those drivers traveling on the highway. It was also suggested that all information be passed on to state legislators; not only was the information gathered, but also the addresses and activities of all Blacks participating in civil rights activities.25 This ultimately culminated in the Commission’s decision to murder Evers. On the morning of June 12, 1963, at approximately 12:20 am, after attending a meeting at the New Jerusalem Baptist Church, Evers arrived home. As Evers got out of his vehicle, he was shot in the back with a high-powered rifle. The shot punctured his lungs, causing internal damage. His wife Myrlie emerged after hearing the shot, followed by their children screaming “wake up, Daddy!” Their neighbor, Houston Wells, heard the shot and immediately called the police. The officers arrived at the scene faster than normal for a Black victim. Despite public acknowledgment by law enforcement of this “dastardly act,” and the suspected rifle being found not far from Evers’ carpark, the police did little by way of investigation. They did name Byron De La Beckwith, a White community member, as a suspect. The trial resulted in a hung jury twice, leaving open for the speculation the true efforts and intent of the prosecution. In fact, the Mississippi Sovereignty Commission utilized its information gathering abilities and financial resources to aid Byron De La Beckwith with his defense counsel in 1963 and 1964. A Sovereignty Commission investigator also provided the information needed on the potential jurors used in the selection process.26 This multi-actor and multi-faceted approach to both taking out civil rights/Black activists and covering up the dirty deeds needed to do so constitutes domestic terrorism. It was multi-layered and far-reaching.

Medgar Evers and the Jackson Movement: “Until Freedom Comes.” | Courtesy of YouTube.

The Freedom Riders

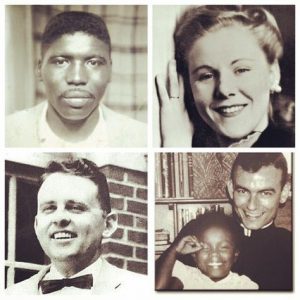

In 1961, a constitutional crisis, otherwise known as the Civil Rights Movement, came to a head in Mississippi. On May 4, seven Whites and six Blacks boarded Greyhound and Trailways interstate buses in Washington, D.C. and headed south. Although the United States Supreme Court ruled in the case of Boynton v. Virginia that racial segregation in interstate travel facilities was unconstitutional, this did not matter in the South. Due to much ongoing racial tension, the Kennedy Administration was hesitant to enforce the Court’s decision. This only further added to the laundry list of reasons that the Freedom Riders decided to take action. Upon the arrival of the Freedom Riders in the state of Mississippi, they were met with extreme violence. They were arrested for a “breach of peace.” The active leaders of the Freedom Riders Crusade were James Chaney, Michael Schwerner, and Andrew Goodman. Michael Schwerner became the main target due to his prominence in the Movement. The Mississippi Sovereignty Commission became very active in surveilling all of the movements of the Freedom Riders.27

After the burning of the Mt. Zion church in Philadelphia, Mississippi, Schwerner, Chaney, and Goodman decided to go and investigate it. It should be noted that in 1964, a Sovereignty Commission investigator gave information to the Neshoba County law enforcement on the Freedom Rider civil rights workers and advised them of a suggested disappearance of the three men as a publicity stunt. Delmar Dennis, a former Ku Klux Klan member in Mississippi who worked for the FBI as an undercover agent for three years during the 1960s, reminisced that information in regards to the Freedom Riders was passed on to the Ku Klux Klan and used against the civil rights workers. Dennis was very instrumental in the case of the Medgar Evers’ murder trial, when he flipped and testified against Byron De La Beckwith. The Freedom Riders left at approximately 4 pm. Goodman was supposed to check in, but he never got the chance to do so. Chaney was making the drive to Philadelphia when they were suddenly pulled over by Sheriff Cecil Price of Neshoba County for speeding.28

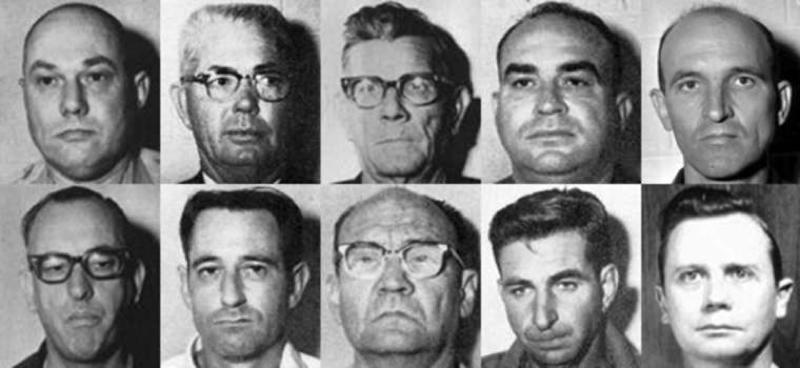

The three men were placed in custody at the Neshoba County jail for investigation. While they were in custody, the Sheriff and the Klan were getting into position to take out the Freedom Riders. This plot was approved by Sam Bowers (Grand Wizard of the Klan) several weeks before the murders took place in Neshoba County. Later that evening they were released, but as they got a few miles away from the station, they were pulled over by a caravan of cars with Klansmen and police officers. After being pulled over, they were taken into a wooded area and all three men were shot and killed. Their bodies were dumped on Old Jolly Farm in a river basin that belonged to Olen Burrage, who was alleged to be a Klansman and possibly linked to the murder of the three victims, but who was acquitted in 1967. There were 18 men named as having a hand in the murder of these three men. Out of the 18 men, eight were convicted, but only one was convicted of manslaughter. These men were Horace Barnette, Jimmy Arledge, Edgar Ray Killen, Cecil Price, Samuel Bowers, Alton Wayne Roberts, Jim Snowden, and Billy Wayne Posey.29 This fatal attack further strengthens the case for domestic terrorism in the United States. These efforts were coordinated and orchestrated across various legal authorities, state-sanctioned organizations, and KKK groups that shared information with law enforcement, with the goal of neutralizing Blacks and racial progress.

Mississippi State Secrets and Dr. J. Horace Gemany. Courtesy of YouTube.

Now, in more recent history

In the case of Graham v. Connor (1989), the Court ruled that a claim of excessive force by police officers during an arrest, stop, or other seizure of an individual is subject to the objective reasonableness standard of the 14th Amendment, rather than a substantive due process standard of the Fourteenth Amendment. This means the facts and circumstances related to using force should drive the analysis, rather than any improper intent or motivation by the officer that used power. Instead, the officers must articulate the facts and events that made the use of force justifiable under reasonable circumstances.30 This standard served only to condone police brutality and give the green light to legitimize the killing of Blacks and Hispanics. This did not guarantee the 14th Amendment’s promise of personal security, regardless of an individual’s race.

Nearly four years ago, on May 10, 2019, Ronald Greene was driving on U.S. Highway 80 in Monroe, Louisiana, when Trooper DeMoss attempted to initiate a traffic stop for an unspecified traffic violation. Instead of stopping, Greene sped away, and a high-speed pursuit occurred. In the event of a high-speed chase, per departmental policy, an officer must stand down if human life is in danger of being lost. The officer involved in the pursuit of a suspect must ensure they have all vehicle information, make, model, and direction of travel and put a BOL (Be on the Look Out) arrest warrant on the suspect, in addition to writing up the police report. This allows them to apprehend the suspect without innocent people getting injured. Eventually, Greene’s car stopped on Louisiana Highway 143 after spinning into a wooded area. Mr. Greene’s vehicle sustained moderate damage on the rear driver’s side, and he was able to exit without assistance. Greene was uninjured and was able to speak and function after the crash. Immediately after that, Louisiana State Trooper officers Dakota Moss and Chris Hollingsworth arrived on the scene.31

Shortly afterward, L.S.P. officers John Peters, John Clary (senior officer on the scene with 31 years of service), Floyd McElroy, and Kory York arrived, along with Union Parrish Sheriff Deputy Christopher Harpin. Greene tried to exit his vehicle and apologize to the officers for his failure to stop. The officers immediately pinned Greene to the ground.32

The actions of the L.S.P. officers took in apprehending Mr. Greene by handcuffing and shackling him by his ankles as Greene begged the officers to stop and repeatedly conveyed his remorse. Greene was then handcuffed and his feet shackled, placing him in a hog-tying position.33

A similar incident occurred in the case of Littlewind v. Rays (1993), involving Littlewind and three other inmates in a racially segregated North Dakota Penitentiary Unit. Littlewind surrendered after an attack on correctional officers and was taken to an observation unit. Upon arrival to the department, Littlewind was stripped naked and placed faced down, handcuffed and his feet shackled and a chain run between the two resulting in Littlewind’s spine being in an arched position. This treatment lasted eight hours and was only removed for forty-minute meal breaks. For the next 23 hours, Littlewind was denied the ability to use bathroom facilities. Littlewind was also denied medical attention with water and toilet being disconnected. Littlewind filed suit, citing the officer’s actions were in violation of the 8th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution Cruel and Unusual Punishment, and filed a lawsuit under section 1983 (42 USC-Civil Action for Deprivation) “under the color of state law.” The Court found that the officer’s actions were so egregious that Littlewind’s 8th Amendment rights were violated, and no evidence showed that the officer’s actions were constitutional.34. Greene endured the same treatment as Littlewind.

The officers on the scene still “beat, smothered, and choked Greene,” not even caring about the fact that he surrendered, and was not resisting. He was in police custody and did not pose an immediate threat to the officers. In the case of Tennessee v. Garner (1985), a state police officer shot and killed Garner as he fled the crime scene. Despite knowing that Garner was not armed, the officer believed that his actions were justified in shooting Garner to prevent his escape. On behalf of the decedent (Garner), his father brought a constitutional challenge to the Tennessee statute that authorized the use of deadly force in this situation. The statute provided that “[i]f, after notice of the intention to arrest the defendant, he either flee or forcibly resist, the officer may use all the necessary means to effect the arrest.” Tenn. Code Ann. § 40–7–108 (1982). The state prevailed in the trial court, but the state appellate court ruled that the statute was unconstitutional. Under the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, a police officer may use deadly force to prevent the escape of a fleeing suspect only if the officer has a good-faith belief that the suspect poses a significant threat of death or serious physical injury to the officer or others.35

Video showing the deadly arrest of Ronald Greene released after two years | Courtesy of Today.

New panel investigating State Police | Courtesy of YouTube.

Ronald Greene’s case is one of many cases in which officers resort to the use of a taser as their first option, rather than resorting to other, lesser, options of force, such as using other officers on the scene to assist with de-escalation techniques that may be more effective than the use of blunt force.36 In the case of Newman v. Guedry (2012), it was established that a law enforcement officer could not throw a non-resisting individual to the ground and shock them multiple times while being beaten by another officer.37 The misuse of tasers is known as the “drive and stun mode,” also see Perea v. Baca (2016).38 This tactic is also known as a pain compliance tactic, a practice commonly used by officers but which should be a last resort, after less painful tactics have been employed.39 Another classic example of the misuse of tasers is the case of Bryan v McPherson (2009). Officer McPherson deployed his taser against Carl Bryan during a traffic stop for a seat belt violation. Bryan filed suit, citing that the officer’s actions violated his constitutional rights. The Court considered if Officer McPherson’s use of a taser during the traffic stop violated Bryan’s 4th Amendment right. In a majority opinion, it ruled that a taser in this situation constitutes excessive force by the officer involved. Bryan was never a threat to the officer and remained stationary outside the vehicle.40

It is not known which officer used the taser on Greene due to L.S.P. Colonel Kevin Reeves’s failure to release the footage on the bodycam, the dashboard footage, discharge logs, use of force reports, or any number of investigative materials that would identify the officer that used lethal force against Greene.41 The issues of lack of cooperation by the Louisiana State Police has been an ongoing issue for decades, for illustration Act#430 the use of body-worn cameras §2551 the use of body-worn cameras legislation that was passed in 2021 has no effect on requiring law enforcement agencies in the state to use body-worn cameras and activate them for any encounters with citizens without any penalty.42 The law only requires that a policy be adopted by the agency. The State of Louisana’s failure to pass legislation requiring law enforcement to wear Body Cameras is only the beginning of the issues facing the state on law enforcement cooperation.43 For months, L.S.P. Colonel Reeves continued to state that Greene was killed due to an automobile accident and continued to refuse to release information about what happened to the public.44 On the night of the incident, the governor of Louisiana was notified of the Ronald Greene incident by text messages, which were recovered. During this time the current governor of Louisiana was in a tight race for re-election as governor. The governor chose to wait until the election was over vs. responding immediately to a human life being taken.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/gray/5VFSFXDRWZGRRBFYLCZFILDESI.jpg)

L.S.P. Col. Reeves’ text message to the governor on Ronald Greene incident. Courtesy of wbrz.com

From the beginning, the L.S.P. officers on the scene and the top brass concealed what really happened to Ronald Greene on the night of May 10, 2019, by telling Greene’s family that he had died from the impact of hitting a tree.45 The call made to Emergency Services was omitted and there was not anything mentioned of an altercation ever taking place. Even the police report did not mention at any point an altercation with Mr. Greene either. The on-duty emergency room physician at the Glenwood Medical Center in Monroe, LA discovered that the events described by the L.S.P. officers were in conflict with the timeline of events. The police report stated that Greene was intoxicated without justification.46 The blunt force that was used left him bloodied and beaten, causing Greene’s cardiac arrest. At 12:29 am, the E.M.S. team arrived after being called to the scene.47

The video clearly shows that Greene was not breathing and was not allowed to be provided any oxygen by E.M.S due to troopers’ refusal to remove the handcuffs from Greene in order to try to revive him.48 Upon the medical team’s arrival at 12:51 am, the response team found Greene covered in blood and multiple taser barbs attached to his body. Greene was unresponsive and was in cardiac and respiratory arrest. Greene’s lifeless body was transported to the hospital, where he was pronounced dead at 1:27 am.49 Mr. Greene’s autopsy was conducted by an Arkansas State Crime Lab pathologist and the Union Parish Coroner’s Office. In the report, it states that it shows that Greene had high levels of cocaine in his system. The report also stated that he had a high-blood alcohol level, which is considered being intoxicated in the State of Louisiana. In the report it does not state the nature in which Mr. Greene died, such as homicide, accidental, or natural causes.50

In an initial report from the hospital, it was reported that Greene had died from cardiac arrest; in addition, there was a diagnosis of an unspecified head injury. Trooper Hollingsworth later confirmed that multiple officers were present.51 Prior to the high-speed chase, Hollingsworth turned off his dashcam and bodycam.

Officer Hollingsworth can be heard on the released bodycam footage stating, “I beat the ever living F**K out of him” to his superior over the phone.52 It was later discovered that the officers watched each other beat, smother, choke, and tase Greene, even though Greene surrendered and did not threaten them.53 In addition, in the autopsy report, multiple signs of trauma were discovered, ranging from blunt force injuries to head and facial lacerations, abrasions, and contusions. There were also signs of blunt force to the extremities and knees.54

Despite seeing all of the evidence of Greene’s having been beaten to death, top L.S.P. commanders pressured investigators to not pursue criminal charges against the troopers involved in Greene’s death. Colonel Reeves and the top brass continued to conceal and obstruct justice, and allowed the officers to remain on the L.S.P. In addition, it was later discovered that Lt. Clary, the senior officer on the scene, who initially told investigators that he did not have any footage of the Greene incident, did in fact have a bodycam on him the night of Greene’s murder.55

This was proven when his 30-minute bodycam footage was released to the public, proving that Clary was not truthful about the video footage. In addition, all of the officers questioned in relation to what occurred on the night of Greene’s death produced conflicting reports.56

L.S.P. investigator Albert Paxton, in the beginning stages of the Ronald Greene case, initially tried to have the officers involved charged in the beating, but leadership in the L.S.P. Department blocked Paxton from charging officers for the beating of Ronald Greene. In addition, Paxton was unable to obtain any of the footage or any other evidence needed to solve the case. Paxton retired shortly after, stating that he would not lie or participate in covering up of evidence in the Ronald Greene case. Shortly afterward, Trooper Carl Cavalier spoke out about the misconduct and the widespread racism throughout the Louisiana State Police Department. Cavalier was fired shortly afterward for criticizing how the Ronald Greene case was being handled.57 What was L.S.P. leadership’s true reason for terminating Cavalier? This was done to protect the blue wall of silence. Under the Violent Crimes and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, 42 U.S.C. & 14141 (“Section 14141”), it is unlawful for government entities such as the L.S.P. to engage in a pattern or practice of conduct in which law enforcement officers deprive citizens of rights, privileges, or immunities secured by the Constitution or laws of the United States.58 It can be argued the L.S.P. Department violated this act by depriving Greene, among others their rights to freedom and life, and against cruel and excessive punishment as guaranteed by the U.S Constitution.

L.S.P. Detective Albert Paxton set to retire. Will not lie about Ronald Greene Case. Ken Paxton at hearing | Courtesy of KTVE

L.S.P. Lt. Clary body cam worn at the scene | Courtesy of KTVE

The Ronald Greene case is one of many cases involving Louisiana State Troopers F, which has become notorious for its brutal treatment of black motorists. In another long-suppressed case of police brutality, a video of a black motorist named Aaron Larry Bowman can be seen being struck in multiple areas with an aluminum flashlight that had a special tip designed to break safety glass by Louisiana State Trooper Brown. Mr. Bowman was struck 18 times in 24 seconds. Brown can be heard yelling in the video, “Give me your F****** hands.” Brown’s justification for striking Bowman with a flashlight was for “pain compliance” to get Bowman to release his hands to be handcuffed. Other law enforcement officers can be seen in the video not attempting to intervene to stop Brown. It is evident that Trooper Brown intentionally failed to report the incident and went on further to obstruct justice by mislabeling the bodycam he wore that day. Trooper Brown is one of the most violent officers in the Troop F division. Brown has 23 uses of force incidents dating back to 2015; 19 of these violent attacks were against blacks. Trooper Brown is a legacy hire, the son of Bob Brown, who was second in command at the Louisiana State Police Department and also has a reputation of being a very violent racist.59

Bob Brown was reprimanded for commenting if those n***as could pass the test to become Louisiana State Troopers. Brown Sr. was also known for calling his co-workers n***as and having a Confederate flag hanging in his office. Trooper Jacob Brown would prove to be the prophetic image of his father, becoming one of the most violent officers, pulling over blacks along the cotton and soybean fields of Louisiana where he grew up.60

Both Bob Brown and his son Jacob Brown both represent the current and past culture of nepotism and pure racism in the L.S.P. Troop F Department, and the us vs. them culture created when the L.S.P. chain of command allows the killing of innocent Black men and, afterward, suppressing the evidence.61 The Louisiana State Police racist discriminatory training practices of brutality against Blacks goes as far back as the civil rights movement and these same brutal tactics that are used today could be compared to the tactics of the Interstate Sovereignty Commission ( Mississippi, Louisiana, Alabama) up to today. In one particular case, a motorist had been stopped for possession of an illegal substance based on their race. A law enforcement official that was involved confessed to being trained with an infamous training video where troopers who trained by LSP officers were instructed by superiors to conduct pretextual stops as justification for pulling over people of color, which included not only just Blacks, but Cubans, Columbians, Puerto Ricans, and other races. The video was never recovered to prove that the traffic stops were racially motivated; however, it is described precisely the race-based training in the video as to how distasteful the values of not only the department but the nation for not addressing the issue in the description of the racist video. Throughout all of these horrible vicious reports of police brutality in the state, there has not been any moves made to discipline or decertify any of these officers. In addition, police departments benefit from hiring officers that have prior misconduct offenses because they do not have to train them and they can pay them a lower salary. And they just go to another racist police department. This is how the L.S.P. maintains control, through the fear of violence in the state by allowing a toxic culture of racist policing that is deeply embedded in the state police culture.62 This type of policing dates back to a staunch racist and segregationist by the name of Leander Perez, who served as a district judge, district attorney, and the president of Plaquemines Parish Commission Council in Plaquemines, Louisiana.

Leander Perez controlled Plaquemines Parish as an absolute dictator, and allied with racist politicians during his era, such as Strom Thurmond, Lester Maddox, and George Wallace. Perez was a devoted racial segregationist. If you did not abide by his terms, you were targeted. To demonstrate his hatred, Perez constructed a military-style prison that was infested with snakes for anyone who came from the outside to protest for equality in Plaquemines Parish.63 The L.S.P., similarly, is an organization that is racist to the core, including the terrorists acts that commit these acts to intimidate Blacks and make them afraid, and the racist law enforcement top brass that conceal the evidence of the cruel vicious beatings and deny justice to the victims.

Trooper Jacob Brown striking Aaron Bowman at home | Courtesy of YouTube

The malicious acts of violence against Ronald Greene and many other people of color come from pure hatred to cause pain or even death. The role that law enforcement serves is like that of military forces occupying another nation, only it is in the black and brown communities. This issue of police brutality results in the disappearance of jobs and a lack of access to educational opportunities, as well as to traditional skill trade jobs that were taken out of schools during the 60s, in urban areas where people of color reside. This all created an environment of lawlessness, and as a result the creation of the “War on Drugs” slogan, gutting the 4th and 6th Amendments and creating an environment of tension in the Black and Hispanic communities against law enforcement, giving the police the green light to abuse and terrorize people of color.

Malcolm X on White Policemen | Black Lives Matter | Maktoob | Courtesy of Youtube

Call to action

The time is now to deal with the issue of domestic terrorism that has been unleashed on the black and brown in our nation since the days of Reconstruction. The old Louisiana Jim Crow mindset has never died. On May 10, 2019, Ronald Greene, our brother, was murdered by L.S.P. officers who committed terrorist acts of violence against someone who was no threat, as in the cases of many other men of color who suffer pain and sometimes death. The truth about what really happened to Greene has been hidden, with nothing presented but pure lies. Since the murder of Greene, Lt. Clary has been reinstated and the charge of obstruction of justice was thrown out by a judge in exchange for a testimony of negligent homicide against Trooper York, who made Greene lay on his stomach for over 9 minutes faced down and handcuffed, and dragged Green as shown on the body cam video.64 Trooper Jacob Brown was acquitted after violating the civil rights or Aaron Bowman by a federal jury, and leaving him with a broken jaw.65 The leadership of the Louisiana State Police Department and the political hierarchy in the State of Louisiana, who are in positions of power to bring about justice, stand idle and do nothing, aiding in these terrorist acts against the black and brown and covering up these vicious acts of violence. The time has come for all of us as citizens, even the good police officers who are truly trying to do what is right, no matter what your race, to speak out on the injustices that continue to occur in this nation. Everyone has the power to vote and hold all elected officials accountable for doing what they are elected to do. The time is now to come together and remove all of the Bull Connors from office and elect those who will see people being treated fairly and receiving fair justice. We need to start labeling these acts of state-sponsored terrorism as such. This conduct, pursuant to the legal definition, constitutes domestic terrorism and should be prosecuted. 18 United States Code section 2331(5) defines “domestic terrorism” as follows: “activities that— (A) involve acts dangerous to human life that are a violation of the criminal laws of the United States or of any State; (B) appear to be intended— (i) to intimidate or coerce a civilian population; (ii) to influence the policy of a government by intimidation or coercion; or (iii) to affect the conduct of a government by mass destruction, assassination, or kidnapping; and (C) occur primarily within the territorial jurisdiction of the United States. . . “The applicable portion of this codification is (B)(i), because law enforcement agencies perform acts that intimidate or coerce a civilian population — that being the black population. (A) and (C) are elements easily met by the commissions of murder and attempted murder.66 In the wake of persistent police brutality, with the most recent homicide victim being Tyre Nichols, these unjust and unchecked terrorist acts need to be recognized as such. Civil rights warriors have moved the needle a great deal, but we need the cooperation of state and federal governments. Criminally codifying this behavior perpetrated by law enforcement is possibly the only solution that will have actual effect, as nothing until today has served to effectively deter such criminality; in fact, it seems to be on the rise.

This article is dedicated to those who paid and fought for equal justice, and who paid the ultimate price, and those who were recently victims of police brutality. Justice for Caron Nazario and Tyre Nichols.

This article is also dedicated to those who made the ultimate sacrifice so that we have the freedoms we have today.

- Justice, CRIMINAL RICO : 18 U.S.C. §§ 1961-1968 (a Manual for Federal Prosecutors) (Lulu.com, 2013). ↵

- L. M. G., “Rizzo v. Goode: Federal Remedies for Police Misconduct,” Virginia Law Review 62, no. 7 (November 1976): 1259, https://doi.org/10.2307/1072250. ↵

- ABC News, “ABC News,” ABC News (ABC News, 2019), https://abcnews.go.com. ↵

- Jill Nelson, Police Brutality: An Anthology (W. W. Norton & Company, 2001), 25. ↵

- Sam Levin, “A Beach Town Seized a Black Couple’s Land in the 1920s. Now Their Family Could Get It Back,” The Guardian, April 17, 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2021/apr/17/bruces-beach-willa-charles-manhattan-beach-la-county. ↵

- Jill Nelson, Police Brutality: An Anthology (W. W. Norton & Company, 2001), 25-26. ↵

- Jill Nelson, Police Brutality: An Anthology (W. W. Norton & Company, 2001), 26-27. ↵

- Jill Nelson, Police Brutality: An Anthology (W. W. Norton & Company, 2001), 26-27. ↵

- Samuel Issacharoff et al., The Law of Democracy, Legal Structure of the Political Process (Foundation Press, 2022), 65-66. ↵

- Samuel Issacharoff et al., The Law of Democracy, Legal Structure of the Political Process (Foundation Press, 2022), 65-66. ↵

- Samuel Issacharoff et al., The Law of Democracy, Legal Structure of the Political Process (Foundation Press, 2022), 65-66. ↵

- Len Sandler, The Centennial Scandal (Len Sandler, 2021), 192 – 200. ↵

- Len Sandler, The Centennial Scandal (Len Sandler, 2021), 192 – 200. ↵

- Len Sandler, The Centennial Scandal (Len Sandler, 2021), 192 – 200. ↵

- Len Sandler, The Centennial Scandal (Len Sandler, 2021), 192 – 200. ↵

- Len Sandler, The Centennial Scandal (Len Sandler, 2021), 192 – 200. ↵

- Len Sandler, The Centennial Scandal (Len Sandler, 2021), 192 – 200. ↵

- Len Sandler, The Centennial Scandal (Len Sandler, 2021), 192 – 200. ↵

- Sarah Rowe-Sims, “The Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission: An Agency History – 2002-09,” www.mshistorynow.mdah.ms.gov, September 2002, https://www.mshistorynow.mdah.ms.gov/issue/mississippi-sovereignty-commission-an-agency-history. ↵

- Yasuhiro Katagiri, The Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission (University Press of Mississippi, 1997), 3-9. ↵

- Yasuhiro Katagiri, The Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission (University Press of Mississippi, 1997), 45. ↵

- Yasuhiro Katagiri, The Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission (University Press of Mississippi, 1997), 22. ↵

- W. Ralph Eubanks, Ever Is a Long Time (Basic Books, 2007), 85. ↵

- Yasuhiro Katagiri, The Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission (University Press of Mississippi, 1997), 55-63. ↵

- Yasuhiro Katagiri, The Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission (University Press of Mississippi, 1997), 40. ↵

- Nina Renata Aron, “In 1956, the Racist Governor of Mississippi Started a Secretive Commission to Fight Integration,” Medium (Timeline, September 21, 2017), https://timeline.com/mississippi-state-sovereignty-commission-4450b7f056a3. ↵

- Yasuhiro Katagiri, The Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission (University Press of Mississippi, 1997), 95-96. ↵

- Yasuhiro Katagiri, The Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission (University Press of Mississippi, 1997), 163-164. ↵

- U.S. Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division United States Attorney’s Office, Southern District of Mississippi Federal Bureau of Investigation, “Michael Schwerner – James Chaney – Andrew Goodman,” www.justice.gov, March 8, 2018, https://www.justice.gov/crt/case-document/micheal-schwerner-james-chaney-andrew-goodman. ↵

- US Supreme Court, “Graham v. Connor, 490 U.S. 386 (1989),” Justia Law, 2019, https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/490/386/. ↵

- UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT WESTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA MONROE DIVISION, “Greene v. DeMoss, CASE NO. 3:20-CV-00578 | Casetext Search + Citator,” casetext.com, April 2, 2021, https://casetext.com/case/greene-v-demoss-2 ↵

- UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT WESTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA MONROE DIVISION, “Greene v. DeMoss, CASE NO. 3:20-CV-00578 | Casetext Search + Citator,” casetext.com, April 2, 2021, https://casetext.com/case/greene-v-demoss-2 ↵

- UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT WESTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA MONROE DIVISION, “Greene v. DeMoss, CASE NO. 3:20-CV-00578 | Casetext Search + Citator,” casetext.com, April 2, 2021, https://casetext.com/case/greene-v-demoss-2 ↵

- United States District Court, D. North Dakota, Southwestern Division., Littlewind v. Ray: 839 f.supp. 1369 (1993) (Judge Goldberg October 1, 1993). ↵

- “APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT, “Tennessee v. Garner, 471 U.S. 1 (1985),” Justia Law, March 27, 1985, https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/471/1/.. ↵

- UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT WESTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA MONROE DIVISION, “Greene v. DeMoss, CASE NO. 3:20-CV-00578 | Casetext Search + Citator,” casetext.com, April 2, 2021, https://casetext.com/case/greene-v-demoss-2 ↵

- Newman v. Guedry, et al, no. 11-41192 (5th Cir. 2012). (KING, SMITH and BARKSDALE, Circuit Judges.JERRY E. SMITH, Circuit Judge December 21, 2012). ↵

- Appeal from the United States District Court for the District of New Mexico , Perea v. Baca (LUCERO, HARTZ, and GORSUCH, Circuit Judges. April 4, 2016). ↵

- Appeal from the United States District Court for the District of New Mexico, Perea v. Baca (LUCERO, HARTZ, and GORSUCH, Circuit Judges. April 4, 2016). ↵

- United States Court of Appeals, Ninth Circuit., Bryan v. MacPherson (HARRY PREGERSON, STEPHEN REINHARDT and KIM McLANE WARDLAW, Circuit Judges. June 8, 2010). ↵

- UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT WESTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA MONROE DIVISION, “Greene v. DeMoss, CASE NO. 3:20-CV-00578 | Casetext Search + Citator,” casetext.com, April 2, 2021, https://casetext.com/case/greene-v-demoss-2. ↵

- Wesley Muller, Louisiana Illuminator July 7, and 2021, “New Police Reforms Coming to Louisiana,” Louisiana Illuminator, July 7, 2021, https://lailluminator.com/2021/07/07/new-police-reforms-coming-to-louisiana/. ↵

- Wesley Muller, Louisiana Illuminator July 7, and 2021, “New Police Reforms Coming to Louisiana,” Louisiana Illuminator, July 7, 2021, https://lailluminator.com/2021/07/07/new-police-reforms-coming-to-louisiana/. ↵

- UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT WESTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA MONROE DIVISION, “Greene v. DeMoss, CASE NO. 3:20-CV-00578 | Casetext Search + Citator,” casetext.com, April 2, 2021, https://casetext.com/case/greene-v-demoss-2. ↵

- UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT WESTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA MONROE DIVISION, “Greene v. DeMoss, CASE NO. 3:20-CV-00578 | Casetext Search + Citator,” casetext.com, April 2, 2021, https://casetext.com/case/greene-v-demoss-2. ↵

- Wesley Muller, Louisiana Illuminator April 30, and 2022, “Coroners’ Records Missing on Ronald Greene Death,” Louisiana Illuminator, April 30, 2022, https://lailluminator.com/2022/04/30/coroners-records-missing-on-ronald-greene-death/.. ↵

- UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT WESTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA MONROE DIVISION, “Greene v. DeMoss, CASE NO. 3:20-CV-00578 | Casetext Search + Citator,” casetext.com, April 2, 2021, https://casetext.com/case/greene-v-demoss-2. ↵

- Wesley Muller, Louisiana Illuminator April 30, and 2022, “Coroners’ Records Missing on Ronald Greene Death,” Louisiana Illuminator, April 30, 2022, https://lailluminator.com/2022/04/30/coroners-records-missing-on-ronald-greene-death/. ↵

- UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT WESTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA MONROE DIVISION, “Greene v. DeMoss, CASE NO. 3:20-CV-00578 | Casetext Search + Citator,” casetext.com, April 2, 2021, https://casetext.com/case/greene-v-demoss-2. ↵

- Celine Castronuovo, “Autopsy Report, Full Body Camera Footage Released from Ronald Greene’s Deadly Arrest,” The Hill, May 22, 2021, https://thehill.com/homenews/state-watch/554920-autopsy-report-full-body-camera-footage-released-from-ronald-greenes/. ↵

- UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT WESTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA MONROE DIVISION, “Greene v. DeMoss, CASE NO. 3:20-CV-00578 | Casetext Search + Citator,” casetext.com, April 2, 2021, https://casetext.com/case/greene-v-demoss-2. ↵

- LSP whistleblower fired for exposing ‘toxic brotherhood.’ Louisianaweekly.com. (n.d.). Retrieved July 17, 2022, from http://www.louisianaweekly.com/lsp-whistleblower-fired-for-exposing-toxic-brotherhood ↵

- UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT WESTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA MONROE DIVISION, “Greene v. DeMoss, CASE NO. 3:20-CV-00578 | Casetext Search + Citator,” casetext.com, April 2, 2021, https://casetext.com/case/greene-v-demoss-2. ↵

- UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT WESTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA MONROE DIVISION, “Greene v. DeMoss, CASE NO. 3:20-CV-00578 | Casetext Search + Citator,” casetext.com, April 2, 2021, https://casetext.com/case/greene-v-demoss-2. ↵

- UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT WESTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA MONROE DIVISION, “Greene v. DeMoss, CASE NO. 3:20-CV-00578 | Casetext Search + Citator,” casetext.com, April 2, 2021, https://casetext.com/case/greene-v-demoss-2. ↵

- John Mustian, “AP: Body Cam Prompts New Look at What Killed Black Motorist,” AP NEWS, July 7, 2021, https://apnews.com/article/death-of-ronald-greene-e9474dfffbe1d37f7e1ff711a32f2e2d. ↵

- John Simerman, “State Police Detective Who Claimed Coverup in Ronald Greene Case Files to Retire,” NOLA.com, January 4, 2022, https://www.nola.com/news/article_142621fc-6db5-11ec-914a-33786708faed.html. ↵

- “Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994,” H.R.3355 – Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 § (1993), https://www.congress.gov/bill/103rd-congress/house-bill/3355. ↵

- Ashley Mott, “Louisiana Trooper Struck Man 18 Times in 24 Seconds, Concealed Video: LSP Warrant,” The News-Star, December 11, 2020, https://www.thenewsstar.com/story/news/crime/2020/12/11/lsp-trooper-hit-aaron-bowman-18-times-concealed-video-warrant/3896936001/. ↵

- Ashley Mott, “Louisiana Trooper Struck Man 18 Times in 24 Seconds, Concealed Video: LSP Warrant,” The News-Star, December 11, 2020, https://www.thenewsstar.com/story/news/crime/2020/12/11/lsp-trooper-hit-aaron-bowman-18-times-concealed-video-warrant/3896936001/. ↵

- Jim Mustian and Jake Bleiberg, “In Louisiana, a Father, a Son and a Culture of Police Abuse,” https://www.fox8live.com, October 26, 2021, https://www.fox8live.com/2021/10/26/louisiana-father-son-culture-police-abuse/. ↵

- Alanah Odoms and Nora Ahmed, “Re: Pattern-Or-Practice Investigation into Louisiana State Police,” August 27, 2021, https://www.laaclu.org/sites/default/files/8.27.21_letter_to_doj_re_lsp_investigation.pdf.. ↵

- Glen Jeansonne, “Leander Perez,” 64 Parishes, November 1, 2022, https://64parishes.org/entry/leander-perez. ↵

- “Jim Mustian, “Grants Pass Daily Courier,” thedailycourier.com (AP, December 18, 2023), https://hosted.ap.org/dailycourier/article/094df0d875f7dce6f6b280bc43a78be6/louisiana-state-police-reinstate-trooper-accused.. ↵

- “Federal Jury Acquits Louisiana Trooper Caught on Camera Pummeling Black Motorist,” wwltv.com (The Associated Press, August 3, 2023), https://www.wwltv.com/article/news/local/louisiana-state-police-trooper-aquited-black-man-beating/289-73cec854-0da8-4764-9684-2ee417efb653. ↵

- Justice, CRIMINAL RICO : 18 U.S.C. §§ 1961-1968 (a Manual for Federal Prosecutors) (Lulu.com, 2013) ↵

3 comments

LEE

This is very nice work. I am really impressed about the amount of work you did. I tried to read all of it and it was nice summary overall. And I love that many pictures are contained in this work. Thank you for your job and thank you for introducing this story with us. It is quite heavy topic but i always am interested in this kind of stuffs. Police and domestic people’s problem kind of thing.

Robert Amie Sr

This is the ground work of becoming a US Supreme Court Justice. Great Job Christopher.

Dr. Meghann Peace, Ph.D.

Christopher, I am amazed and so proud of the incredible work that you did on this! It is the entire history of our nation’s attacks on its own people, specifically, its people of color. You placed the recent police brutality in its entire historical and sociocultural context. And you did it in addition to all of your regular work. This is incredible! Thank you for letting me be a part of this with you!