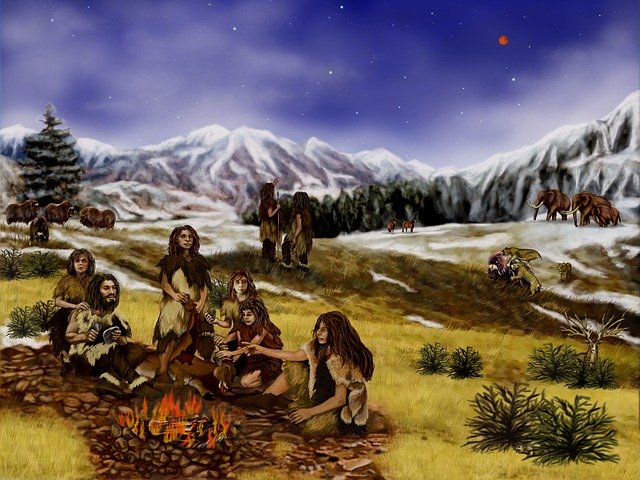

It was early in the morning, and the tribesmen were out hunting for game. The group of young hunters started to look for tracks of their prey to follow. One of the hunters called out as he found a large group of hooved animals tracks. As they followed the tracks, the group spotted a herd of antelope. There was some tall grass off to the side of the herd that they used to move closer to them, without being spotted by the prey. The hunt spread through the foliage to allow for a greater chance to land a kill, but while this was being done, they were unaware of another type of hunter within the grass. The hunters slowly moved to avoid scaring their prey. To finish the hunt quickly, they each started to ready their weapons, throwing spears made from sticks with sharpened rocks tied to the ends. Suddenly, one of the younger hunters was knocked down to the ground by a wolf that had been obscured by the grass. The sounds of the struggle scared off the antelopes and alerted the rest of the hunt. The group ran to the sounds of battle to help their tribemate. They quickly reached the hunter and, then they saw a wolf mauling the young man. Their spears were readied, and then they thrusted them at the wolf. They drew blood from the animal and caused the wolf to yelp and it ran away from the group. After driving off the wolf, the group checked on the hunter, but they didn’t arrive fast enough to prevent significant damage to the young man from the attack. Looking at him, they saw him bleeding along his chest and arms, and there was an indent on his head. The members of the hunt quickly grabbed the now-injured young man and they ran back to the tribe, and they took their injured mate to the shaman. Being a hunter was a dangerous job in this time of hunter-gatherer societies. It was easy for the hunter to become the hunted, with various other predators willing to take an opportunistic chance to pick off a member of the human hunting groups. The smaller animals could also be dangerous, like snakes with their venom or insect swarms that might continuously sting those who came near their nests. Even the prey that was being hunted had ways to defend themselves, with their horns or with their sheer weight to charge at a hunter.1

July 12, 2018 7:12 pm

wolf hiding in grasses

There was also the fact that early humans, like those in this tribe, had no idea of bacteria and the infections that came from improperly cared-for wounds. Due to that, many minor injuries could easily turn into fatal illnesses. Unfortunately for the tribesman, his compatriots hadn’t done much to prevent his bleeding, and while grabbing him, his wound was rubbed against the ground, and bacteria gained access to his body.2

Soon the hunting group returned to the tribe’s camp. The tribeswomen walked over in confusion, due to it being earlier than expected for a hunting group to return, and those that returned would usually talk to them. But this time the men all rushed past the women. Then they saw the blood all over some of the hunters and on the ground, due to them taking turns carrying the wounded one. There was blood over many of them. They quickly rushed over to ask questions, to gain information from them about what happened to them during the hunt. Those that did not stay behind to answer questions quickly took him to the tribe’s medicine man. He would have told the panicked group to have laid the injured man out on a bed. He then looked over the male and noted the swelling around the wounds and dirt, and while his head swelled, it began to turn purple. The mother of the young man came and saw what happened to her child and was horrified at the sight of what happened to her offspring. The shaman quickly tried to calm her down and told her that everything was going to be alright. He then told the hunters that he wanted to be left with the patient and that the mother could stay to look after her son. The shaman began to gather ingredients from his tent: some leaves, berries, and mushrooms from the local area, with some ashes from the camp’s fire, animal bones, and a bit of water. He then placed them all into a mortar and pestle, and then he then ground them up into a paste while a tune was sung according to the ways he was taught by his predecessor, in order to bless the paste with the spirits of the land.3

May 23, 2019 12:04 pm

Contemplative shaman with trident on dirty ground

The shaman then grabbed an animal’s bladder, which was used to contain liquids after being removed from an animal and treated to help preserve it. The bladder contained fermented berries and mushrooms and was then poured down the boy’s throat to drive out bad spirits within his body, and it quickly intoxicated the hunter. The paste was then applied to his wounds around his body, mainly around his arm and chest where the wolf bit and clawed at him.4

The medicine man then moved on to the indent on his head. He then looked over the injury again in order to be sure he did not miss anything from before. He then grabbed a ceremonial knife and cut into and around the swelled area in a certain pattern, in order to gain access to the skull. He then grabbed another tool, then placed it against the skull, and began to scrape it against the skull in order to reach the cranium. He removed the bone of the skull, layer by layer. As it breached through the skull, the pieces were removed to prevent them from stabbing into the brain. As the blood flowed out of the wound on the skull, it was believed that it would take with it evil spirits that caused harm to the body. He then applied some more of the paste to the wound and folded the skin of the young man back into the skull and sowed it shut.5 While the shaman was working on the hunter, his father returned from his hunt and was swiftly informed of what had happened to his son. He then picked up his daughter, who had been given over to another family to be cared for while his wife was looking after his son. They rushed over to the shaman’s tent to make sure their family member was going to be alright. As they arrived, the mother was crying about her child. They asked about how he was and what would happen, but they were told that it was not going well, and that as much as possible was being done, and that it took time for them to be sure whether he would survive or not.

During this time, the bacteria that got into the wound got to work doing what they do best: multiply and expand. They used the blood vessels to spread throughout the body, grabbing the nutrients that would normally have gone to the body’s cells. While the body tried to fight the infection by using platelets to try and seal the wound to prevent any new diseases, the white blood cells would try to kill the invaders by dissolving and eating them, and the body would puff and heat up in order to limit what the bacteria would be able to do to harm the body. In this situation there weren’t much these defenses would have been able to do to protect the body. The wound was too big for the platelets to have been strong enough to seal the wound to prevent exposure. White blood cells took time to properly produce the right ones that were suited for that disease and there were too many entry points to stop the bacteria before it could spread further into the body, and something was preventing the white blood cells from traveling effectively. While inflammation was the most effective of these three, it was also rapidly draining the body’s resources, but it could only have done so much with the rapid spread of the infection. Medicine during this time was not as reliable as it is today. Any effective medicine was made through trial and error, and healing was believed to have been through calling to one’s gods or to the spirits to drive out demons that caused sickness and wounds. The tools of this time were mainly rocks fashioned into various tools and were often improperly cared for and disinfected by modern standards.6

June 07, 2016

PURPLE BELL FLOWERS

Some of the medicine that was used during this time was even poisonous. The leaves used in the paste above we call Digitalis lanata, which is a plant that contains the compound Digoxin. These chemicals cause abnormal heart function that reduces one’s heart rate, and in sufficient amounts, can cause heart failure.7 The removal of parts of the skull by the shaman was called trepanning. While it was done for a spiritual reason, it was actually something that helped, and there has been evidence that some of those that underwent it survived and were able to live on with a relatively normal life. When the young tribesman hit his head upon a rock, it damaged his brain and caused internal bleeding, which increased pressure within the brain as blood flowed in without a way to flow out. By his skull being opened, it allowed a way out for the pressurized blood, but unfortunately, it could often allow a way for bacteria to get into the brain, as it did with the current patient.8

While the young man’s body tried to fight off the infection, the rest of the tribe went on with their tasks in order to made sure that the tribe did not suffer from a lack of food or lack of tools and other things. His family stayed by his side while his body tried to fight off the growing infection, worrying about his ever-worsening health, even though the medicine man tried multiple different rituals and medicines to attempt to heal him. After a few days, his body failed him, and he died, and his family grieved for his passing. The tribe then placed him in their fire in order to send his spirit to be with those of his ancestors. Soon after this was done, the tribe packed up and moved on, and left his ashes behind to move onto a different place to hunt and live.9 Situations like this would have happened many times over in this time before history, where millions had died with no one having any idea of who they were or what they had gone through.

- Donna Hart, Man the Hunted : Primates, Predators, and Human Evolution, Expanded Edition, vol. Expanded ed (Boulder, CO: Routledge, 2009), 97-104. ↵

- Christopher Wanjek, Bad Medicine : Misconceptions and Misuses Revealed, From Distance Healing to Vitamin O (New York: Wiley, 2003), 21. ↵

- Ian Dawson, Prehistoric and Egyptian Medicine (Enchanted Lion Books, 2005), 8-10. ↵

- Matthew Parsons MA and Shari Parsons Miller MA, “Fermentation,” in Salem Press Encyclopedia of Science (Salem Press, 2019),. ↵

- Robert Arnott, Stanley Finger, and Chris Smith, Trepanation (CRC Press, 2005), 165-167. ↵

- David S Kushner, John W Verano, and Anne R Titelbaum, “Trepanation Procedures/Outcomes: Comparison of Prehistoric Peru with Other Ancient, Medieval, and American Civil War Cranial Surgery,” World Neurosurgery 114 (June 2018): 245–51,16. ↵

- Mustafa Adem Tatlisu Kazim Serhan Ozcan Baris Gungor Ahmet Zengin Mehmet Baran Karatas Zekeriya Nurkalem, “Inappropriate Use of Digoxin in Patients Presenting with Digoxin Toxicity,” Inappropriate Use of Digoxin in Patients Presenting with Digoxin Toxicity, no. 2 (2015): 143. ↵

- David S Kushner, John W Verano, and Anne R Titelbaum, “Trepanation Procedures/Outcomes: Comparison of Prehistoric Peru with Other Ancient, Medieval, and American Civil War Cranial Surgery,” World Neurosurgery 114 (June 2018): 245–51. ↵

- Fanny Bocquentin et al., “Emergence of Corpse Cremation during the Pre-Pottery Neolithic of the Southern Levant: A Multidisciplinary Study of a Pyre-Pit Burial,” PLoS ONE 15, no. 8 (August 12, 2020): 1–44, . ↵

27 comments

Rhys Kennedy

This is a very interesting and particular article about ancient medicine. It was very informational regarding how one might expect prehistoric people, who really had no concept of medicine, to deal with health issues that would regularly arise. The details regarding the rituals were interesting to read about given that I have never really read about them.

Danielle Slaughter

Hey, Ian.

This was a truly fascinating article. I suppose on often takes for granted the miracles of modern medicine, when in reality, someone could die from a simple scratch before the advent of antiseptics and antibiotics. I especially enjoyed learning about the spiritual element to it all — that ancient humans placed their faith in something higher than themselves to help.

Sara Alvirde

This article was very interesting to read about especially the part about the shaman using animals stomach that had food in them to be digested which was made me feel squirmish but I couldn’t stop reading how insane these rituals were.

Monserrat Garcia Rodriguez

Very interesting article! I have never given it much thought to how people used to self medicate before scientist and doctors so reading this article gave me another perspective on history. It is also very interesting to see how human civilization has evolved in the aspect of medicine and available doctors there are… Thank you for this article!

Azariel Del Carmen

I found this topic to be curious as I knew for a fact that practices in health and other factors were way different back in the day, compared to what we have now. I don’t know much way back in the past but I do think the practices at the time were odd and had risks unknown to many that while it could cure someone might harm them in the long run. I’m glad that the practices here evolved over time and that we are able to manage health better in the past and this describes what has happened between pre-times and now.

Camila Garcia

This article was very well written and informative. The first paragraph was very detailed and really captivating. I feel as if prehistoric events are not discussed as much as they should be and the author did a good job doing so. It is interesting to see how early medicine was developed and how they used spiritual beliefs when trying to aid someone.

Valeria Varela

It was really fascinating to read how simple wounds can turn fatal as they didn’t know how to fight off infections. But I enjoyed reading of the connections that were made with medicine being intertwined with spirituality at the time.

Allison Grijalva

Hi Ian! I did not have much prior knowledge about prehistoric life and honestly did not give it much thought before reading this article. I do think the flow was a little shaky throughout, however I loved the content as whole. Your connection to medicine is an interesting one and made me think about the trial and error it took to achieve modern medicine. Great job!

Faith Chapman

Writing a historically fictional story about the subject was clever, and was probably the best way to convey the historical facts presented in this article. I liked how the article didn’t bash on the treating rituals of hunter-gatherer societies, partly because they couldn’t know what we do today (like poisonous substances and bacteria), but also because some of the things they did, like the trepanning and the concoction he made the patient drink, which I figured sort of worked like anesthesia, are credible, which is notable because they were able to do this despite being unable to know what we know today. I did find it surprising that the shaman/healer was male and not female, although it’s possible that the gender of the shaman didn’t matter and the shaman just happened to be male in this story.

Madeline Chandler

In all honesty, I had no idea about this part of early history of early tribesmen. It is very interesting that they did not truly know or understand about wounds or infections or that certain acts made it worse. I thought it was really interesting and kind of terrifying that shamans shoved parts of animal bladders down peoples throat to intoxicate them. Thank you for sharing this unique mythical part of early history.