A talking river called Rio Rimac: In Lima, Perú the river called “Rio Rimac” or “Talking River”, is famous for its importance to the community and the ancient myth that surrounds it. The myth of this river tells the story of Rimac, who lived next to his father “Inti”, the Sun, and the other gods in the superior world “Hanan Pacha”. Rimac would visit the human world to tell beautiful stories, and the humans loved him. One day, Rimac and the other gods asked his father to liberate the humans from a great drought, and Inti answered that if they wanted to get water, according to the law a god had to sacrifice his life to provide water. Chaclla, one of Inti’s most virtuous daughters, volunteered herself for the sacrifice, but Rimac, who loved his sister, asked his father to take his life instead. Rimac and Chaclla were not able to get to an agreement with Inti, and both decided to sacrifice themselves to break the drought. With their sacrifice, they were both transformed into water, Chaclla becoming rain, and Rimac changing into the busiest river on the Peruvian Coast. The story says that if you pay attention closely to the river, you can still listen to Rimac telling stories.1

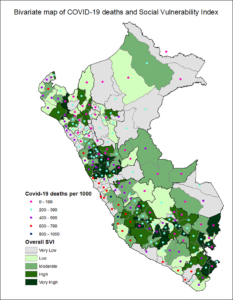

The LISA method has also been used in Perú to find areas where social vulnerability links to COVID-19 (Figure 3), and it could also be used to find areas along the Rio Rimac where there are high levels of social vulnerability and groups of domestic wastewater or high levels of solid contaminants. These types of geospatial methods could help to find areas that not only focus help on the socially vulnerable but also help to reduce river contamination at the same time.

A chance for a new tale: In 2018, the Peruvian Ministry of Environment (MINAM) launched a campaign employing motion sensors and speakers that mimicked the voice of the Rio Rimac whenever someone attempted to toss their trash in the river. The aim was to raise awareness among the public, and remarkably, 80% of individuals who heard the simulated voice of Rio Rimac refrained from disposing of their waste in the river. This innovative approach to protecting an endangered environmental resource shows the potentially strong links between cultural narratives and scientific research in developing effective environmental policy.

Rio Rimac has experienced numerous changes throughout its history, marked by both efforts to protect it and actions that worsened its condition. However, the preservation of the river is not the responsibility of a single individual, but rather a collaborative effort involving various organizations. It does not matter if it is a comprehensive action plan to restore the river’s health, an ingenious campaign to sensitize the people, or just someone promoting taking care of it, this river needs all the help possible, and every possible help counts.

- Colchado Lucio Ó, Ycaza R. 2015. La doncella que quería conocer el mar: y otras leyendas peruanas. 1a ed. Lima: Ministerio de Educación.Santillana, S.A.,1947-2023. ISBN: 978-612-01-0302-9. ↵

- Carlos Andrés Gamero Esparza (leondeurgel). 2017. 22814393_1560804290665015_3971029877622548815_n.accessed 2023 Nov 7. https://www.flickr.com/photos/leondeurgel/26323359129/. ↵

- Lossio J. 2003. Acequias y gallinazos: salud ambiental en Lima del siglo XIX. 1a ed. Lima, Perú: IEP Instituto de Estudios Peruanos (Colección Mínima). ↵

- Canziani Amico J. 2012. Ciudad y territorio en los Andes : contribuciones a la historia del urbanismo prehispánico. Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú. Fondo Editorial. https://repositorio.pucp.edu.pe/index/handle/123456789/170305. ↵

- Aronson J, Renison D, Rangel-Ch JO, Levy-Tacher S, Ovalle C, Pozo AD. 2007. Restauración del Capital Natural: sin reservas no hay bienes ni servicios: Ecosistemas. 16(3). ↵

- Río Rimac, historia del #RíoHablador ??. wwwyoutubecom. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_1LauQJV9Y0. ↵

- Guillén G. O, Cóndor Evaristo EV, Gonzáles Torres MA, Iglesias León S. 1998. Contaminación de las aguas del Río Rímac: Trazas de metales. Revista del Instituto de Investigación FIGMMG. ↵

- Observatorio del Agua Chillón Rímac Lurín. (2019). Diagnóstico Inicial para el Plan de Gestión de Recursos Hídricos de las cuencas Chillón, Rímac, Lurín y Chilca (p. 151). Lima, Perú. ↵

- Ministerio de agricultura (ANA). 2014. CUENCA RÍMAC EN PELIGRO. accessed 2023 Dec 5. https://infografiasos.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/cuenca-1.jpg?w=450. ↵

- Autoridad Nacional del Agua. 2015. En 10 años se recuperará calidad del río Rímac. Lima, Peru. ↵

- K-water, Yooshin Engineering Corporation, Pyunghwa Engineering Consultants.2015.Plan maestro del proyecto de restauración del río Rímac: Informe final. Lima, Peru. ↵

- Plan Maestro de Recuperación del Río Rímac. wwwyoutubecom. accessed 2023 Nov 29. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hGVUp1-jgoY. ↵

- GESTIÓN N. 2020 Apr 21. Coronavirus Perú: Río Rímac presenta aguas cristalinas tras reducción de basura en un 90% durante aislamiento social obligatorio | Minagri | Sedapal | Estado de emergencia nndc | PERU. Gestión. https://gestion.pe/peru/coronavirus-peru-rio-rimac-presenta-aguas-cristalinas-tras-reduccion-de-basura-en-un-90-durante-aislamiento-social-obligatorio-minagri-sedapal-estado-de-emergencia-nndc-noticia/. ↵

- García Delgado F. 2020 Apr 21. Coronavirus en Perú: el río Rímac se recupera debido a la falta de actividad humana | VIDEO. El Comercio. accessed 2023 Nov 29. https://elcomercio.pe/lima/sucesos/coronavirus-en-peru-el-rio-rimac-se-recupera-debido-a-la-falta-de-actividad-humana-noticia/#google_vignette. ↵

- Zegarra Zamalloa CO, Contreras PJ,

Orellana LR, Riega Lopez PA, Prasad S, Cuba

Fuentes MS.2022.Bivariate map of Social Vulnerability Index and death rate from COVID-19 per 10,000 inhabitants. accessed 2023 Dec 5. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/365965732/figure/fig1/AS:11431281104375017@1670028039694/Bivariate-map-of-Social-Vulnerability-Index-and-death-rate-from-COVID-19-per-10-000.png. ↵ - Zoll D, Lieberknecht K, R. Patrick Bixler, J. Amy Belaire, Jha S. 2023. Integrating equity, climate risks, and population growth for targeting conservation planning. Environmental Science & Policy. 147:267–278. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2023.06.015. ↵