For Roman Jakobson, studying Slavic and Russian linguistics and literature at the University of Moscow just made sense. Having grown up surrounded by academics and having graduated from a high school that specialized in linguistic studies, he was well prepared. So prepared, in fact, that Jakobson quickly disagreed with many of his professors. In his young eyes, the Moscow linguistic school to which many of his professors belonged was too orthodox, too rigid.1 Jakobson yearned to break out of the traditional mold set in front of him in the classroom and plunge the depths of linguistics, but he could not do this within the confines of his university.

Specifically, the professors whom he opposed identified as neo-grammarians. Neo-grammarians were the first to apply a scientific structure to linguistics. Their main focus was in two areas. The first was understanding how different languages are similar. The second was understanding how languages have changed over time. Believing that changes in the pronunciation of words always followed a regular pattern, they were able to build a family tree of languages.2

Yet, once neo-grammarians began to dominate academia in Russia, a new generation of linguists was emerging. These linguists craved to take the study of speech further than their professors. However, the neo-grammarian classrooms in which they sat did not welcome the novel ideas of young scholars like Roman Jakobson.3 Luckily, Jakobson was ready to cause waves within the linguistic community in Moscow, and many others were, too.

Roman Jakobson and his fellow students at Moscow University needed a space where they could discuss their linguistic theories without being immediately shut down by their professors. It seemed they would have to create this space for themselves. In 1915, Jakobson and friends organized the first meeting of the Moscow Linguistic Circle, and Jakobson was named its chairman. At each session, the young men crammed together in the home of whichever member was able to host. There, they contemplated the linguistic issues of the day. One member would throw out an idea. Another would second it. A third might be bold enough to completely contradict them. In the homes of these young linguists, their minds could wander without the restriction of academia.4

Being Russian themselves, the linguists focused on Russian dialectology and folklore. They studied the variations of Russian speech based on location and social distinction. How and why did some Russians pronounce words differently than others? Why might different Russians express themselves differently? The Circle also dove deep into the traditional stories of their country—the fairytales, the myths, the legends—picking apart the literary devices used. Yet, after two years of studying these topics, there was a shift in attention, one that was very important to the work of Roman Jakobson. The Circle turned their eyes to poetry.5

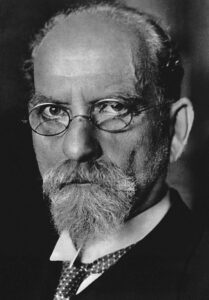

As chairman of the Moscow Linguistic Circle, Jakobson decided the group could greatly benefit from this pivot. In facilitating this change, he was inspired by the work of Edmund Husserl, a German philosopher. Husserl thought of speech logically, causing him to view language as a “system of signs.” To him, each word strung together in a sentence worked jointly to convey a message. He carefully dissected speech into parts and then studied their function. Young linguists like Jakobson were inclined to a similar approach. Jakobson found the structure of language fascinating. Once studied, aspects of language were able to be categorized into what we now call literary devices. Once categorized, the effects of these devices could be studied.6

This very thought process lent itself to the study of poetry. Jakobson and his peers could choose a poem, underline the poetic devices that the author employed, and analyze the function of these devices. The goal was to understand how poets constructed their pieces to achieve the desired effects.7

Another advantage of this literary genre was that neo-grammarians, the critics of the young linguists, preferred to stay far away from it. Viewing poetry as a bit odd and strange, these linguists tended to analyze more “respectable” forms of literature. So, because neo-grammarians had not imposed their theories on poetry, the Moscow Linguistic Circle was able to present their ideas through this medium without opposition.8

Poetry became so important to the Moscow Linguistic Circle that, between the years of 1918 and 1919, the majority of the papers read at their meetings centered around the study of poetry. Many different projects were discussed at these meetings. Some were group endeavors, such as the study of Nikolai Gogl’s “The Nose” by members Bogatyrëv, Brik, Vinokur, and Jakobson. Others were solo studies, such as “On Verse Rhythm” by member Osip Brik, or “The Problem of Literary Borrowings and Influences” by member Boris Tomaševskij. However, the most notable work that resulted from the discussions of the Moscow Linguistic Circle was written by Roman Jakobson himself, titled “Xlebnikov’s Poetic Language.”9

In 1919, Jakobson’s “Xlebnikov’s Poetic Language” was first read to his colleagues in the Moscow Linguistic Circle.10 This piece by Jakobson was not only one of the most important studies to come out of the Moscow Linguistic Circle, but also arguably the most important paper for describing the Circle’s school of thought. For years, the group had been discussing and documenting their ideas, but Jakobson’s piece was the one that clearly defined their beliefs.11 For the next two years, while juggling other projects, Jakobson meticulously fleshed out this analysis further. As a result, he published a longer piece focused on Xlebnikov’s poetry in Prague in 1921 under the title Modern Russian Poetry. The concepts so vital to what would later be known as Russian Formalism were stated succinctly for anyone in the linguistic community who could get their hands on a copy of Jakobson’s work. Thus, Jakobson’s linguistic philosophy finally reached much farther than his colleagues’ living rooms. While this opened his ideas up to the criticism of many, Jakobson was now ready to take it on. Whereas before, his thought processes would have been stifled by the rigid orthodoxy of his professors, now, Jakobson had had ample time to construct and back up his beliefs. His ideas were well thought out and could withstand some healthy debate.12

This was only the beginning of Jakobson’s career in linguistics. From these years as President of the Moscow Linguistic Circle, Jakobson gained valuable experience in administration, research, oration, and writing. Beginning in 1918, Jakobson applied these skills and proved to be a valuable asset to Moscow University where he was accepted as a research associate. Opportunities elsewhere led him abroad in 1920 when he began studying at Charles University in Prague. Because of this, he had to leave his beloved Moscow Linguistic Circle.13

Jakobson’s work in Moscow had previously influenced the linguistic community in Prague, but his arrival in the city furthered this fact. In 1926, he helped found a similar linguistic circle in Prague as well, largely based in Russian Formalism. This Prague Linguistic Circle pioneered its own novel ideas just like its cousin in Moscow and helped construct the school of Prague Structuralism.14

In looking back, it is clear that Jakobson had come a long way in such a short amount of time. At the beginning of his university education, he had only hoped to make a mark on the linguistic sphere. Although he had not agreed with the views of his professors, there was not much room for deviation. Still, Jakobson, along with his colleagues, paved a path for a new kind of linguistic thought: Russian Formalism.15 Barely thirty by the time he helped found his second linguistic society, Jakobson had many more important contributions to make to linguistics. And so he would continue, utilizing the foundational skills he acquired in his time in the Moscow Linguistic Circle.

- Julia S. Falk, “Roman Jakobson,” in Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia (Salem Press, February 28, 2021. ↵

- Aristotle Katranides, “Three Linguistic Movements: Neogrammarianism, Structuralism, Tranformationalism,” presented at the TESOL Convention, San Francisco, California, March 18-21, 1970. ↵

- Aristotle Katranides, “Three Linguistic Movements: Neogrammarianism, Structuralism, Tranformationalism,” presented at the TESOL Convention, San Francisco, California, March 18-21, 1970. ↵

- Victor Erlich, Russian Formalism : History – Doctrine, 4th ed, vol. 00004, Slavistic Printings and Reprintings (The Hague: De Gruyter Mouton, 1980), 63-64. ↵

- Victor Erlich, Russian Formalism : History – Doctrine, 4th ed, vol. 00004, Slavistic Printings and Reprintings (The Hague: De Gruyter Mouton, 1980), 64. ↵

- Victor Erlich, Russian Formalism : History – Doctrine, 4th ed, vol. 00004, Slavistic Printings and Reprintings (The Hague: De Gruyter Mouton, 1980), 61-62. ↵

- Victor Erlich, Russian Formalism : History – Doctrine, 4th ed, vol. 00004, Slavistic Printings and Reprintings (The Hague: De Gruyter Mouton, 1980), 63. ↵

- Victor Erlich, Russian Formalism : History – Doctrine, 4th ed, vol. 00004, Slavistic Printings and Reprintings (The Hague: De Gruyter Mouton, 1980), 63. ↵

- Victor Erlich, Russian Formalism : History – Doctrine, 4th ed, vol. 00004, Slavistic Printings and Reprintings (The Hague: De Gruyter Mouton, 1980), 64. ↵

- Julia S. Falk, “Roman Jakobson.,” in Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia (Salem Press, February 28, 2021. ↵

- Victor Erlich, Russian Formalism : History – Doctrine, 4th ed, vol. 00004, Slavistic Printings and Reprintings (The Hague: De Gruyter Mouton, 1980), 65. ↵

- Victor Erlich, Russian Formalism : History – Doctrine, 4th ed, vol. 00004, Slavistic Printings and Reprintings (The Hague: De Gruyter Mouton, 1980), 65. ↵

- Elmar Holenstein, Roman Jakobson’s Approach to Language : Phenomenological Structuralism (Bloomington, Ind. : Indiana University Press, 1976), 192-193, http://archive.org/details/romanjakobsonsap0000hole. ↵

- Elmar Holenstein, Roman Jakobson’s Approach to Language : Phenomenological Structuralism (Bloomington, Ind. : Indiana University Press, 1976), 192-193, http://archive.org/details/romanjakobsonsap0000hole. ↵

- Julia S. Falk, “Roman Jakobson.,” in Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia (Salem Press, February 28, 2021. ↵

16 comments

Sudura Zakir

Greetings, I found this article intriguing since it shows how literature can be both beautiful and effective because it contains truth and purpose. Roman Jakobson enjoyed it, and it was obvious. It’s also fascinating to learn about his work with linguistics and how language affects the globe as a whole. He noticed the alteration in word and accent and discovered a connection between linguistics and Roman Formalism.

Maya Naik

I thoroughly enjoyed reading your article and wanted to congratulate you on your well-deserved nomination! Your writing was detailed, well-structured, and truly engaging. Before stumbling upon your article, I had never heard of Roman Jacobson. His story, however, was fascinating and I admired his dedication to fostering creativity among his colleagues and creating an open space for exchanging ideas. Thank you for sharing this enlightening piece.

Michaell Alonzo

Hey Gabriella, congrats on being nominated for an article award. This post was so beautifully written and fascinating to read. This page has an astonishing quantity of specific information. Learning more about linguistics and Jakobson’s work was intriguing, especially since poetry played a significant role in their discussions and processing of the material. Prior to reading your paper, I was unaware of Jakobson and had no knowledge of him. I really liked the pictures you chose, which perfectly complemented the narrative you were presenting. I really appreciated how well-organized you were; it made the reading interesting for me.

Aaron Astudillo

Congratulations on your article receiving a nomination for a potential award. It is excellently structured and I did not have any previous knowledge of Roman Jakobson, so it is interesting to view the impact his poetry has on society. Furthermore, reading about his history in linguistics shines a light on how this correlates to the art of writing.

Kristen Leary

Congratulations on your article receiving a nomination for an award! You have a real talent for researching an interesting topic and then arranging it in a way that keeps the reader engaged. The writing was very well done, as was the usage of images to add to the article.

Melyna Martinez

Hello, something interesting about this article is how beautiful poetry can be and impactful as well, as it holds truth and meaning. Roman Jakobson had a fondness of it and it showed. As well his involvement in linguistics and the language’s overall impact on the world is so interesting. He saw the change in language and pronunciation finding a correlation with Roman Formalism and linguistics.

Luke Rodriguez

This was a fantastic read! Also, congrats on the nomination! It was well-deserved. The article was well-written and detailed. This was a well-structured article, and I truly enjoyed reading this. Before reading this, I did not know who Roman Jacobson was. His story intrigued me, and I admired his efforts to cultivate creativity among his colleagues and establish a space where thoughts could be exchanged.

Barbara Ortiz

Congratulations on your nomination for such a great article. It was fascinating to learn more about linguistics and Jakobson’s work, especially how poetry became an integral part of their meetings and processing of the subject. I had not heard of Jakobson before your article, nor knew anything about linguistics studies coming out of Moscow. This was well written and I know you are going to continue to thrive on your academic journey in history and language.

Marissa Rendon

I am not so familiar with Roman Jakobson. I found this article to be interesting, there truly is a study for everything. I was not educated on linguistics until I read this article. This is an educational article, I think reading this can help educate people. Excellent article!

Jacqueline Galvan

Going into this article, I had no prior knowledge of Roman Jakobson. I was fascinated by his story and thought that the work he did to foster creativity in the minds of his peers and create an environment where ideas could be shared without the fear of retribution most definitely contributed to his legacy and success in linguistics and poetry, and the success of his peers and those who were also inolved in the Moscow Linguistic Circle.