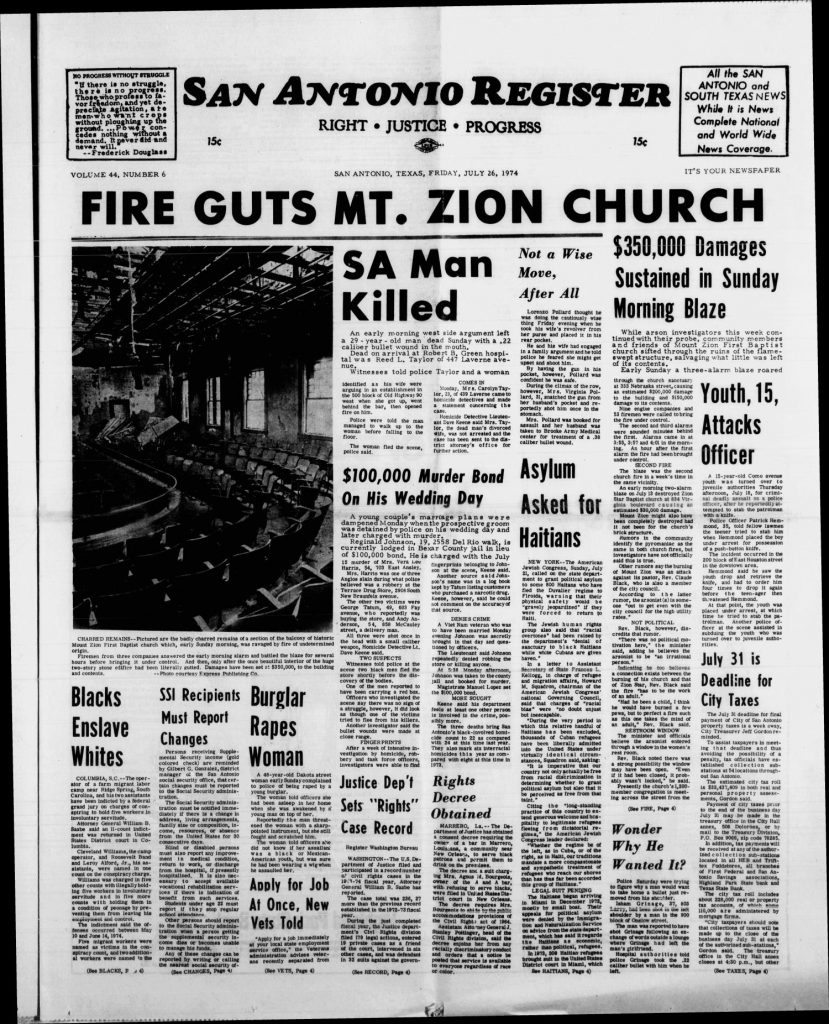

Early one Sunday morning on July 21, 1974, Mt. Zion First Baptist Church members awakened, not from the alarms of clocks set to be ready for church, but from the sirens of three different departments that filled the morning air. The lights colored the sky red, blue, and white. The colors of freedom ironically were driving to put out the flames of a wretched act. This was the second fire in a week that occurred at the church. The first fire that occurred on July 13 was just as devastating. The church was left with nothing but debt — the total cost of the damage was estimated to be around $350,000. They gazed upon the First Baptist being engulfed by flames, disheartened.1 Earlier that year, the reverend of the church was the victim of a drive-by shooting. No one was found guilty of the crime.2 This was not the first time that Mt. Zion had been the victim of hateful acts and violence. Why has this church received so much hate? Mt. Zion is a historic African American church, founded by free slaves on the east side of the San Antonio River in Texas. Because of this legacy, this church is rich with history that cannot be destroyed.

When the first settlers established the city, they designated that Black members would live to the east of the San Antonio River. Twenty-two slaves made their mark on the East Side when they established a church in 1817, with only one white missionary, the Rev. J.P. Hines. The fire damaged the church twice in 1890, but church members rebuilt it.3 Mt. Zion has contributed greatly to the Eastside because it has helped the community grow stronger. Mt. Zion filled and responded to the needs of the community and the larger city. People in the community put in a lot of time to help do this work. In 1951, purchased a home just north of the church that is known by the community as “The House Next Door.”4 In 1957, a day care was opened by the members. On April 12, 1966, they were granted a charter for the only black church-sponsored financial institution in San Antonio. 10. “Claude Black born”, https://aaregistry.org/story/claude-black-born Accessed May 6, 2019] Members dedicated this church to the civil rights movement. Reverend Claude Black Jr., who led Mt. Zion, was a key figure in the civil rights movement in San Antonio and the South.

About thirty years prior to the fire, the Rev. Black was studying to become a doctor but felt a call deeper in his soul to go into ministry. He graduated from Andover Newton Theological School.5 He traveled around seeking positions as a pastor, finding some in Massachusetts, one in Corpus Christi and finally one in San Antonio at Mt. Zion First Baptist Church in 1949. Here he found his true calling of giving back to the community he grew up in and fighting the social injustices that the Eastside faced.

In 1868, the 14th and 15th amendments gave black people equal protection and the right to vote. Many felt the country was finally going in a step in the right direction. It had been two years since the Civil War ended and five years since the Emancipation Proclamation. However, this was still not enough. Racism was still deeply embedded in American culture, especially in the deep-south states that were once part of the Confederacy. The total population of the United States in 1870 was 38,558,371, and the black population was about 4,880,009 including slaves and freed persons.6

The population did not have the backing nor numbers to push on their own terms, but the terms of those who skinned glowed with privilege and basic rights did. This led to the emergence of the “Jim Crow” laws in the late 19th century. These laws segregated public facilities, towns, and schools. Interracial marriage was illegal and most black people were unable to vote due to failing voter literacy tests.

During the Civil Rights Movement in San Antonio, Texas was a quiet town in comparison to other southern states but this does not excuse the hateful actions toward minority communities that took place. The population of San Antonio in 1960 was 588,000. About only 41,605 Black people resided in San Antonio, increasing by 12,876 since 1950. By 1960, the black population made up about seven percent of the city’s residents.7 Although the city never passed a segregation ordinance, the culture and Police Department enforced the separation. Black people were restricted to living in only certain areas of San Antonio due to redlining. Although racial tensions existed, there were no white supremacist movements.8 The black community did not receive the same amount of resources that other communities got. Although the Mexican American community was also segregated on the Westside, they had civil rights and social privileges that Black people did not.9 The Westside helped blur the lines of segregation and the fight against colorism once they were aware of issues that were going on.

Because of the inequalities implemented on black people, the Eisenhower administration pressured Congress to consider new legislation regarding civil rights. On September 9, 1957, President Eisenhower signed the Civil Rights Act of 1957 into law. It allowed the federal prosecution of anyone who tried to present someone from voting and mission to investigate voter fraud. Then in 1964, Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, followed by the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the Fair Housing Act of 1968.

Throughout the late 1950s and 1960s, the Rev. Black organized marches all over the state of Texas alongside state Representative G.J. Sutton and San Antonio activist Harry Burns. He challenged the San Antonio mayor Walter McAllister and Texas Governor Price Daniel for their complacency and establishment of unequal treatment and negative attitudes towards minorities that existed in San Antonio. In 1952, Black attended a city council meeting to voice his opinion. The council ignored him every time he tried to speak. He wanted to be acknowledged not only for his own sake but for the black community. Finally, they addressed him, but with a racial slur that boomed on the council member’s microphone, exposing the racism and tensions that still existed in a town that was built by people of color.The Rev. Black associated with well-known civil rights movement leaders such as Martin Luther King, Thurgood Marshall, and Ella Baker, not knowing that he would become an icon limited to San Antonio but also the South and Baptist community. 10

A massive demonstration against police brutality was hosted by the San Antonio Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, which took place downtown. Nothing like this demonstration had ever taken place in San Antonio before. SNCC-Panthers organized the march for Bobby Joe Phillips, a man beaten to death by the San Antonio Police Department. They marched during the Kings River Parade, triggering an armed attack on the SNCC offices. The Rev. Claude Black offered his support after the event. He began allowing different activist groups, like SNCC-Panthers and the San Antonio Committee to Free Angela Davis to use the church to hold meetings and raise funds.

There he stood, staring at the fire, watching it lick the walls, pews and pulpit on a summer morning. As an icon and leader of the community, he knew he had the responsibility to take on, this was his meaning in life. Helping the community and giving back. As the expenses were calculated and examiners were finished at the crime, rumors began swirling like flames from the fire. The rumors were about the intentions behind why the church was set up in a blaze. The San Antonio Register questioned the Rev. Black if the fire was perhaps intended to make a statement towards him being a council member. The Rev. Black had just become a council member the year before and ended his term in 1978. However, he voiced strong confidence that the church was not under attack but of his position but because a person had strong hate in their heart. He reported to the San Antonio register that this was not a child’s or teen’s game but an adult who was “an irrational person.”11

The Eastside is still known for being the Black community in San Antonio today and it is still very underfunded. I conducted an interview for stories about the Westside and a resident from the Eastside, Fransisco shared his story with me. Fransisco is studying Environmental Sciences and working with children through tutoring and teaching different sports all over San Antonio. When I was asking him about his connections to the Westside he answered, “I know I get in political debates with my colleagues about how the Eastside is a little more deprived than the Westside.” He continued to share his story about going to high school on the Eastside and how low the graduation rate is and how much lower it is for the students to go to college. His final remarks about the Eastside were,

“I think it feels neglected, I know the Westside is given lots of opportunities and it is heavily focused on, which is amazing. But I think they should look at the Eastside. The programs they already have there they should give us, it’s about equity.”12

He expands on his own struggles and why he is passionate about giving back to the community that gave to him when he was in his time of need. He also shared stories of discrimination against him while shopping at Whole Foods and volunteering. He finished the interview by sharing his finals thoughts with the political climate and the communities that are most impacted are low income. The culture of those who live there is full of rich culture and history that can never be destroyed. This is something that is still occurring to this day with social activists that still continue the hard work.13

The Rev. Black left a strong legacy that still resounds very strongly within the community of the Eastside. Social activists like Mario Salas and T.C. Calvert worked with the Eastside to help the community flourish. Salas once worked with the Rev. Black and is faculty at the University of Texas in San Antonio. He has been an advocate for the Eastside since the 1970s. Salas was a key member of the SNCC-Panthers chapter in San Antonio and a founding member of other activist groups including Organizations United for Eastside Development, the Black Coalition on Mass Media and Frontline 2000. Calvert created a community-based and organized group, the Neighborhoods First Alliance, which advocates for environmental justice, safe and affordable housing, health care and education. He is also the founder of the San Antonio Observer and nonprofit community radio station KROV-FM. 14

- “Fire Guts Mt. Zion Church,” San Antonio Register, July 26, 1974. ↵

- Charlotte McReynolds, “The Civil Rights Movement in San Antonio,” http://colfa.utsa.edu/users/jreynolds/HIS6913/McReynolds/intro.htm Accessed May 6, 2019. ↵

- “Mount Zion First Baptist Church History 1871-2018”, https://www.mountzionfbc.org/history.php. Accessed May 6, 2019. ↵

- “Mount Zion First Baptist Church History 1871-2018”, https://www.mountzionfbc.org/history.php. Accessed May 6, 2019. ↵

- “Rev. Claude Black”, http://www.blackworshipsa.com/speakers/rev-claude-black/. Last Accessed May 6, 2019. ↵

- “1870 Census: Volume 1. The Statistics of the Population of the United States”, Last Modification (n.d.), Accessed on May 5, 2019, https://www.census.gov/library/publications/1872/dec/1870a.html. ↵

- Robert A. Goldberg, “Racial Changes on the Southern Periphery: The Case of San Antonio, Texas 1960-1965, The Journal of Southern History. ↵

- Robert A. Goldberg, “Racial Changes on the Southern Periphery: The Case of San Antonio, Texas 1960-1965, The Journal of Southern History. ↵

- Letter from Mario Marcel Salas to Reverend Claude Black – March 10, 1975. https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth290880/. Accessed May 6, 2019. ↵

- “Claude Black born,” https://aaregistry.org/story/claude-black-born. Accessed May 6, 2019. ↵

- Fire Guts Mt. Zion Church” Vol. 44, No.6, Ed. 1, (San Antonio, San Antonio Register) July 26, 1974. ↵

- Interview with Francisco by Shine Trabucco, April 13, 2019. ↵

- Interview with Francisco by Shine Trabucco, April 13, 2019. ↵

- Sanford Nowlin, Greatest Hits & Deep Cuts: San Antonio Activists Making A Difference,” March 8, 2019. https://www.sacurrent.com/sanantonio/greatest-hits-and-deep-cuts-san-antonio-activists-making-a-difference/Content?oid=20360636. ↵

28 comments

Aaron Sandoval

I really enjoyed reading this article, I don’t know a lot about the different areas of San Antonio, aside from some brief information on the westside. So this article opened my view on the culture and situation on the east side, I had never known of the many issues that faced the east side. I am glad that this article was written and I hope that it gets more attention.

Camryn Blackmon

Hi Shine,

Your article is so important. San Antonio is a pretty segregated city even today. I really love that you highlighted the history, especially with racism and the formation of the Eastside as a predominantly Black community. It was also very powerful to include an interview with a student that grew up and experienced what you had discussed in the article.

Caroline Bush

Great article! I lived in San Antonio for a small portion of my life and had no idea that this historic church even existed. This article did a great job showing the beauty in a are that many unfortunately deem “dangerous” or “bad part of town. “I was impressed by Rev. Black and his continued pursuit of justice and equality for all. This article did a wonderful job of shining a light on apart of San Antonio’s black history that many might not know about and showing Rev. Black’s important impact on that history.

Yamel Herrera

I really enjoyed this article because it was very informative about the history of San Antonio to which I was unfamiliar with. I was most moved by Rev. Black’s response that “an irrational person” was to blame for the fire set in the church. This speaks volumes of his character and highlights the intensity of racial segregation in San Antonio at the time. Unfortunately, the Eastside remains to be under funded and is stamped with the racial bias that resulted from the history of its racial segregation.

Donte Joseph

Personally, I did not know very much about the history of San Antonio, let alone its segregation and activism. This is a great article because it sheds light on the history that is not known to all. It is a shame that this article was a reality back then, that black people were subjected to specific neighborhoods that decreased in value just because they inhabited the area. I am glad that there are people like Rev. Black who do their best to make a difference.

Kayla Sultemeier

This article is absolutely correct when stating that the East side of San Antonio is the most underrepresented and most overseen district of San Antonio. This is an area that people often try to avoid because it has a reputation of being “dangerous.” It is sad to think about the labels that are placed on an area as a whole, especially when considering that these exact labels that San Antonio natives have placed upon it is what holds the community back. They do not receive the proper amount of resources or funding because their is such a large misconception surrounding the neighborhood. It definitely does not receive the same treatment as the West side, and deserves much more recognition.

Alexandria Garcia

Wow. I learned so much in this article. I used to go to church on the East side and I always knew that the bulk of the black population was on the East side and sprinkled throughout the West side because of military and government facilities. As a child I took notice to the conditions of the East side but I didn’t know how segregation and racism was instated considering we are a large minority community. I enjoyed learning about Rev. Black and his impact in the community in addition to black history in San Antonio that is not usually talked about.

Briana Montes

This article sparked my interest because it is about segregation in the old days here in San Antonio. This piece discusses the past about this city and i didn’t know it was this serious. It’s sad to think that police would murder someone over their color. no one deserves this however it still occurs.

Andrea Degollado

When i clicked this article I assumed that it would be Talking about segregation and activism on other parts of the United States, I had no idea it would be talking about the East side of San Antonio.I think its very interesting to read the Black was the first one to initiate such activism in San Antonio and bring awareness of the harsh treatment the black community was facing.

Malleigh Ebel

I knew about most of the events discussed by this article, but not in such depth. The segregation problem of San Antonio, especially with redlining, has always been a problem, but its surprising how it is still a problem in the 21st century. I did not realize the the Zion Baptist Church was burned more than once; this article was eyeopening.