Winner of the Fall 2019 StMU History Media Award for

Best Overall Undergraduate Research

“I have proved and believe that change is possible even after a long period of uncertainty, challenge, isolation, despondency, rejection, hopelessness, and anger,” said Jane.1 Jeanne “Jane” Mukuninwa was born in the village of Lulingu, in Shabunda Democratic Republic of Congo sometime in the 1990s.2 She lived in her village with her parents and was a little girl full of joy, innocence, and freedom. Before the civil war, she played with other children under the rain, went to the river and the farmlands, and ran through the streets with no fear. Jeanne and her family were safe and lived in peace. One of the few problems she experienced before the war was lack of education, and like many her age, she was not able to read or write.3 However, this problem was nothing compared to what was to come. At fourteen years old, her entire life was transformed by the horrors and darkness of the civil war.

The civil war in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) was and is a regional conflict that began in 1994 and officially ended in 2003, but political, social, and economic issues have been ongoing. This conflict began in an aftermath of the Rwandan genocide when the Ugandan and the Rwandan governments invaded the DRC in 1996 with the intention to terminate the refugee génocidaires that were living in eastern Congo. The outcomes of this war, referred to as the First Congo War, were that Uganda, Rwanda, and the Congolese opposition leader Laurent Désiré Kabila would overthrow the DRC dictatorship government of Mobutu Sese Seko. Nine African countries were involved in the Second Congo War and because of this, it is better known as The African World War. The Second Congo War lasted five years and was one of the deadliest international conflicts since World War II. This war was caused when the new government of the DRC feared that Uganda and Rwanda were going to take control of the mineral resources of the region, and asked them to leave Congo. Instead of leaving, these groups united forces with militia groups and caused harm to the civilians and killed the president of Congo at that time, Kabila (father). In 2002, two peace accords were signed by Congo, Uganda, and Rwanda.4 However, the domestic issue inside Congo was not finished. This was the cause of displacement, immigration, disease, and sexual violence throughout the country. Even though the DRC is the richest country in the world when talking about its mineral resources, it has become a place in which its people are among the poorest in the world. From 1993 to 2003, tens of thousands of people were killed, and numerous others raped and mutilated by both Congolese groups and foreign military forces.5 Approximately 200,000 women and girls were assaulted, with the north-eastern provinces of DRC being the most affected areas and girls ages ten to seventeen years old being the most vulnerable.6

When Jeanne was fourteen years old, she became an orphan due to her parents’ disappearance in the middle of the civil war conflicts, and their bodies were never found. They were presumably massacred during the fighting, and Jeanne never saw them again. As a consequence of this, she moved with her uncle from her mother’s side of the family and his family. Immersed in deep pain since the loss of her parents, she didn’t know that this was just the beginning of her suffering. Before the war, she did not know the meaning of the word “rape,” but soon after the rumors from other villages about it started to increase, fear came over her and other women. Shortly after she moved in with her uncle, the Hutu militia attacked her village. The family was inside the house when they heard some commotion outside and locked the door for security. Since the door was not strong, the militia broke it down and went inside the house. The Hutu militia stole everything that was in the house of value and made them walk and carry the things for days. If any person in the group complained about anything they were killed instantly.7 This day, the militia not only stole their belongings, but also brutally tortured her uncle by cutting off his hands, gouging out his eyes, cutting off his feet, cutting off his sex organs, and then just left him like that. He was still alive.8 After that, the militia kidnapped her aunt, cousin, and her. Jeanne Mukuninwa remembered clearly; that was the day of her first and last menstrual period. After that day, she understood clearly what the meaning of the word rape was.

“Rape is a weapon even more powerful than a bomb or a bullet. At least with a bullet, you die. But if you have been raped, you appear to the community like someone who is cursed. After rape, no one will talk to you; no man will see you. It’s a living death.”9 Sexual violations have a negative and destructive effect on families, affects people physically, psychologically, and increases the propagation of diseases among the population. In the DRC, rape is used as a war weapon and its victims struggle each day to have rehabilitation. Mass rape is a key weapon in this conflict since the different militia groups utilized it to silence the people, control communities, territories, and natural resources. Since the act of raping a woman terrifies her, humiliates husbands and fathers, and makes the family feel less and weak, it is used as a tool to coerce entire communities into silence. Also, in many of these communities, the women that are raped become rejected by men or even expelled from the community. Through silencing the community, the militia groups gain security, authority, and domination, and justice is made almost impossible. Studies confirm that sexual violation rates are higher in areas where there are mineral resources available. This means that through sexual violations, the community is weakened, and it is easier to control its natural resources. Other reasons why sexual violations are used as a tactic of war in the DRC are as spiritual rites, to humiliate, terminate pregnancies, increase food insecurity, express frustration and anger, and retaliate. Sexual violations are “cheaper than bullets, and more destructive in many cases.”10 In one attack in April 2018 committed by the Mai-Mai militia, at least sixty-six women, eleven girls, and two men were raped and gang-raped. Mass rape is a continuous menace to the DRC’s public health since approximately 1994. According to the United Nations’ Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO), in 2018 there were 1,049 cases of conflict-related sexual violence against 605 women, 436 girls, 4 men and 4 boys.11 Sadly, these numbers can increase if governmental institutions do not do something to stop this.

When people were captured by the militia, if they were men, they were most likely trained to be porters, and if they were women like Jeanne, they were used to cook and as sex slaves. Any man could countlessly rape her, and sometimes she was even raped by rifles and sticks.12 Constantly, Jeanne and other girls were tied spread-eagle and gang-raped; consequently, Jeanne quickly became pregnant. Since her body was not prepared to receive the baby, a doctor, who had been kidnapped by the militia, opened her by cutting into her stomach without anesthesia or disinfected utensils, in order to save her life. After taking out the dead baby, parts of the baby’s body remained inside of Jeanne. Because of this, her uterus was decomposing and made her produce a foul smell that permeated through her mouth and genitals. Jeanne was no longer useful as a sex slave, and the militia threw her to the street, almost dead. Walking alone while almost dying, she managed to get to the Panzi Hospital, where Dr. Mukwege performed nine surgeries to save her life and her reproductive system. The Panzi Hospital is a foundation that earned global recognition as a treatment center for victims of sexual violence in conflict. Dr. Mukwege is the foundation’s director and a gynecologist who gained worldwide recognition and received the Nobel Peace Prize in 2018.13

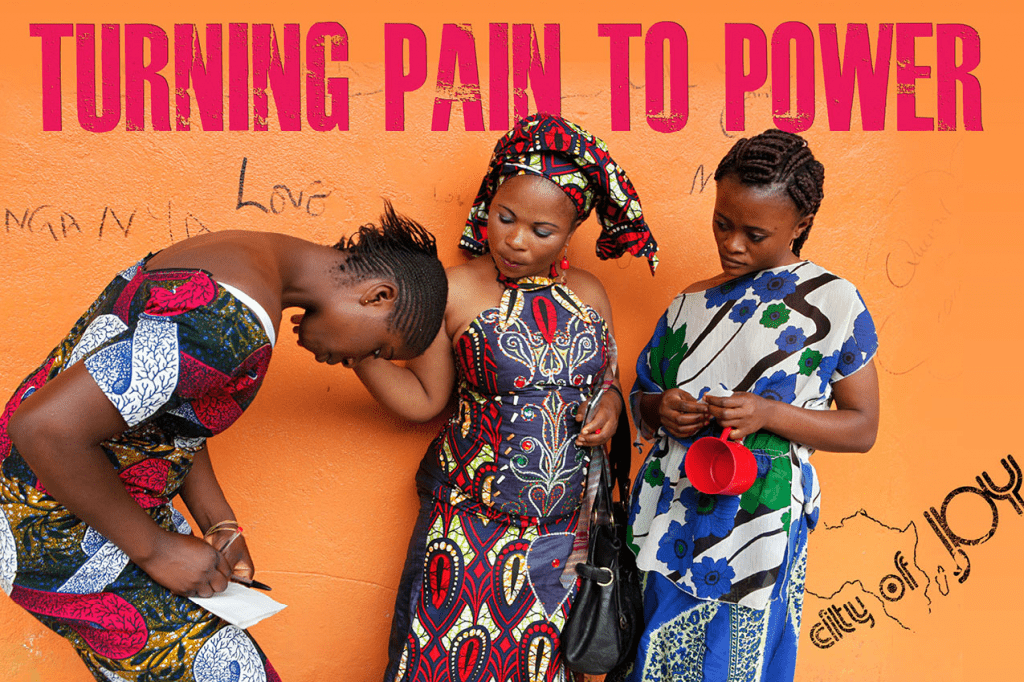

After surgeries and recovery, Jeanne returned to her village with hope; however, that hope was soon destroyed. The militia returned to her village and raped her again. She was left naked in the forest for days until she found her way back to the Panzi Hospital.14 People routinely came to see all the sexual violence victims at the hospital. Because of this, Jeanne, together with other women, “felt humiliated [when] being filmed and photographed like animals in a zoo.”15 However, one day a woman named Eve Ensler went to the hospital and asked the victims what she could do to help. Hopeless and without trust in the promises made by Eve Ensler, these women answered that they wanted a place where they could feel secure, heal, tell their stories and be empowered.16 These women, Jeanne included, wanted a place of refuge for their bodies and their souls. Actually, Jeanne was the one that spoke up for all the women in the group. This conversation with Eve Ensler changed everything in Jeanne’s life and birthed a place of restoration, the foundation, City of Joy.

The sexual violence in the Democratic Republic of Congo is a consequence of the economic disaster that began in 1996 and produced the Civil War. Tunataka nini?…Tunataka nyumba na amani. What do we want? We want a home and peace.17 Women were afraid of returning to their communities after what they experienced, so they asked for a home and peace. Founded in June 2011, the City of Joy in the Democratic Republic of Congo is a non-profit organization made, owned, and run by local Congolese people. The purpose of this organization is to empower and rehabilitate victims of sexual violence. The organization is located in Bukavu, Eastern DRC, and has aided over 1,200 women.18 Jane calls the City of Joy a place where joy, self-confidence, love, hope, and ferocity are regained after a period of trauma, isolation, despair, and uncertainty.19

Programs like the City of Joy are examples of non-governmental organizations that address public health issues where governments lack the ability to respond and act. Non-governmental programs like this one are mainly funded by donations from individuals and professionals like gynecologists and advocates against sexual violence. In the case of City of Joy, Dr. Denis Mukwege and Eve Ensler, an American feminist activist are primary donors. City of Joy works to improve public health within the DRC by providing education, psychological help, gynecologists, and self-defense training. This community is called the City of Joy because, according to Jeanne, “Women who come from their villages carry a burden of trauma and are unable to speak. Many believe they have lost hope and can’t do anything better. When they enter the City of Joy, they start breathing the air of joy because they are embraced. They smile for the first time after they have been assaulted and they find people who want them to feel at ease.”20 The City of Joy serves ninety survivors of gender violence from ages eighteen to thirty. For each six-month period, the City of Joy offers an intense program of education and training where women learn valuable life skills like agricultural knowledge, reading, writing, self-defense, and many more.21 The City of Joy believes women are not victims; rather, they are survivors, and each woman is valuable to her society no matter what they experienced. Women have the right to be treated with dignity and each woman is capable of activating their own recovery process.22 In 2016, City of Joy had the opportunity to create a Netflix documentary film called The City of Joy. This film told the story of the first class of graduates from the City of Joy in 2011.23

When Jeanne first came to the City of Joy, she felt happy and understood. There were people who cared about her. Before the City of Joy, she felt as she was the only woman that had experienced sexual violation; however, at the City of Joy, she heard other women’s testimonies and identified with them. Thanks to this, she understood that she was not alone and that each one of the sexual violence survivors had a unique story. Jeanne became a first-generation graduate from the City of Joy in December 2011. Though Jeanne experienced a very difficult time of torture and rape, after the rehabilitation program of the City of Joy, she was transformed into a totally new person. She transformed her “Pain to Power” like the lemma motto of the City of Joy says, and was able to become a leader to her community and to the City of Joy.24 The change in her life was so significant that she decided to change her name from Jeanne to Jane. She changed her name because of her transformation in the program. “Old Jeanne was full of self-pity, hatred, and suffering. New Jane is independent, young, and a leader.”25

The City of Joy taught Jane to count money, read, sew clothes, write, and even learn English. Presently, Jane works as a staff member at the City of Joy and was part of the 2016 Netflix documentary about the story of the City of Joy and its role in changing and empowering women’s lives. Jane has become an activist and leader for her Congolese community. She wrote two blogs about the V-DAY movement (to end violence against women) in Rise for Justice, which is an international movement that advocates for justice against sexual violence.26 Jane is an instrument of change, and an example and a voice to everyone who experienced the horrors of sexual violence. Being part of the program of the City of Joy allowed Jane to recover her self-love and self-acceptance; she understands that she is a beautiful human being and what she experienced with sexual violence does not change her essence. She declared in an interview with Art at Harvard University, “love has more power than medicine to heal people who have been traumatized and rejected by their communities.”27

- Jane Mukuninwa, “Congo Rising: Why am I Rising for Justice,” One Billion Rising (blog), January 17, 2014, https://www.onebillionrising.org/4467/rising-justice-jane-mukuninwa/. ↵

- Jeanne Mukuninwa, “Congo Rising: Why am I Rising for Justice,” One Billion Rising (blog), January 17, 2014, https://www.onebillionrising.org/4467/rising-justice-jane-mukuninwa/. ↵

- Lyneoyugi, “How Militia Rape me and Tore me Apart,” Lyneoyugi (blog), March 25, 2013, Lyneoyugi, https://lyneoyugi.wordpress.com/2013/03/25/how-militia-raped-and-tore-me-apart/ ↵

- “ About DRC: History of the Conflict,” Eastern Congo Initiative (website), http://www.easterncongo.org/about-drc/history-of-the-conflict ↵

- “DR Congo: UN Releases Most Extensive Report to Date on War Massacres, Rapes”, October 1, 2010, United Nations News (website), https://news.un.org/en/story/2010/10/354522-dr-congo-un-releases-most-extensive-report-date-war-massacres-rapes ↵

- UNFPA, “Secretary-General Calls Attention to Scourge of Sexual Violence in DRC”, March 1, 2009, United Nations Population Funds (website), https://www.unfpa.org/news/secretary-general-calls-attentionscourgesexual-violencedrc ↵

- Lyneoyugi, “How Militia Rape me and Tore me Apart,” Lyneoyugi (blog), March 25, 2013, Lyneoyugi, https://lyneoyugi.wordpress.com/2013/03/25/how-militia-raped-and-tore-me-apart/ ↵

- Nicholas Kristof, “The world Capital of Killing,” February 06, 2010, The New York Times (online), https://www.nytimes.com/2010/02/07/opinion/07kristof.html ↵

- Aryn Baker, “Survivors of Wartime Rape Are Refusing to Be Silenced,” March 21, 2016, Time Magazine (website), https://time.com/war-and-rape/?xid=homepage ↵

- Michelle Lent Hirsch and Lauren Wolfe, “Conflict Profile: Democratic Republic of Cong,” February 08, 2012, Women Media Center WMC (website), http://www.womensmediacenter.com/women-under-siege/conflicts/democratic-republicof-congo#reasons ↵

- Office of Special Representative of the Secretary- General on Sexual Violence in Conflict, “Democratic Republic of Congo”, March 29, 2019, United Nations, https://www.un.org/sexualviolenceinconflict/countries/democratic-republic-of-the-congo/. ↵

- Lyneoyugi, “How Militia Rape me and Tore me Apart,” Lyneoyugi (blog), March 25, 2013, Lyneoyugi, https://lyneoyugi.wordpress.com/2013/03/25/how-militia-raped-and-tore-me-apart/ ↵

- Panzi Foundation, “Panzi Hospital: Panzi Today,” Panzi Hospital and Foundation (website), https://www.panzifoundation.org/panzi-hospital ↵

- Nicholas Kristof, “The world Capital of Killing,” February 06, 2010, The New York Times (online), https://www.nytimes.com/2010/02/07/opinion/07kristof.html ↵

- Jane Mukuninwa, “Congo Rising: Why am I Rising for Justice,” One Billion Rising (blog), January 17, 2014, https://www.onebillionrising.org/4467/rising-justice-jane-mukuninwa/. ↵

- Jeanne Mukuninwa, “Congo Rising: Why am I Rising for Justice,” One Billion Rising (blog), January 17, 2014, https://www.onebillionrising.org/4467/rising-justice-jane-mukuninwa/. ↵

- Jeanne Mukuninwa: Netlfix Documentary, “City of Joy”, November 11, 2016, https://www.netflix.com/uses/title/80203094 ↵

- “City of Joy,” Last Modified 2019, City of Joy (website), https://www.cityofjoycongo.org/splash/ ↵

- Aida Rocci, “Jane Mukuninwa Interviewed by Art at Harvard University,” December 2015, The City of Joy (website), https://cityofjoycongo.org/jane-mukuninwa-interviewed-by-art/ ↵

- Aida Rocci, “Jane Mukuninwa Interviewed by Art at Harvard University”, December 2015, The City of Joy (website), https://cityofjoycongo.org/jane-mukuninwa-interviewed-by-art/ ↵

- City of Joy, Last Modified 2019, https://www.cityofjoycongo.org/splash/ ↵

- City of Joy, “Program Philosophy: What Make it Different,” The City of Joy (website), Last Modified 2019, https://cityofjoycongo.org/about-city-of-joy/program-philosophy-makes-different/ ↵

- City of Joy, Last Modified 2019, https://www.cityofjoycongo.org/splash/ ↵

- City of Joy, Last Modified 2019, https://www.cityofjoycongo.org/splash/ ↵

- Aida Rocci, “Jane Mukuninwa Interviewed by Art at Harvard University,” December 2015, The City of Joy (website), https://cityofjoycongo.org/jane-mukuninwa-interviewed-by-art/ ↵

- Jane Mukuninwa, “Congo Rising: Why am I Rising for Justice,” One Billion Rising (blog), January 17, 2014, https://www.onebillionrising.org/4467/rising-justice-jane-mukuninwa/. ↵

- Aida Rocci, “Jane Mukuninwa Interviewed by Art at Harvard University,”, December 2015, The City of Joy (website), https://cityofjoycongo.org/jane-mukuninwa-interviewed-by-art/ ↵

58 comments

Maria Obregon

This article was very well written and had so much information on subjects that I did not know much about. I learned a lot by reading it! I think it is very important for us to be aware of the things occurring around the world, and like mentioned, this article was great in presenting this unknown information. Besides that, I have to say that Jane’s story was so heartbreaking, but so inspiring at the same time. She went through such difficult times while still so young, but her life eventually changed for the better, and that makes me so happy.

Yamel Herrera

This was a very moving article. I can’t imagine the kinds of pain these women and children had to endure. I think this article captured the idea that for them the hardships weren’t over once they were able to escape their predators. For many like Jane, she had to endure this torture more than once. Thankfully, there are organizations like City of Joy, that can help these victims and offer them not only a safe haven, but also a chance to start a new life journey of empowerment. I think this article could benefit if it also included an anecdote of some other success stories of victims who were able to overcome their tragedies.

Angela Perez

The history whether positive or negative of African countries is not common knowledge to many of us. This article does a fantastic job of bringing attention to the atrocities that have occurred in countries like the Democratic Republic of Congo, while also bringing into the spotlight safe havens like City of Joy for those who are survivors. I really liked the personalization and transitions of this article from telling Jane’s personal journey to the general information of the war.

Amberlee Flores

I think one of the most important things is being able to stand up for yourself. I know in some situation it is difficult to but at the end it makes a difference in yourself. This article gave me an idea about the African World War that I did not existed. I can not even imagine what some of the girls had to go through. I think that we should all be educated in the history on how girls were mistreated to prevent less cases. These girls were brave to speak up and save themselves.

Andrew Gallegos

I think it’s so amazing how she believes in such an amazing thing that can make an impacted on others. It’s so very important to stand for yourself and let others know you have a voice and your going to stand up for it. It’s inspring how all the rough times she and her family has been going through but she still manages to ourcome them. It’s veyr important to oversee the world to see what is going on and how we as people together can fix it.

Citlalli Rivera

This was such a powerful and moving story! Many times, people who are learning about the atrocities of war from the outside-in dehumanize the victims of war and replace their names with numbers. Thank you so much for respecting and uplifting Jane’s name! It is disgusting that international governments, local governments (the DRC and those surrounding), and other nations do not feel compelled to stop the terroristic attacks on our sisters in the DRC and surrounding areas. Nonetheless, I am moved by Jane’s story and her power to overcome!

Haley Aleman

I think it’s amazing whenever people accomplish amazing things, but i think it’s not only impressive but inspiring when they manage to be more than the situation that they’re in and rise above things that may have set them back. I’ll be 100% honest I’d never heard about the war in Africa. I think it’s very important to educate ourselves about what’s going on in the world around us, even things that have already happened. Even more so when they’re situations that are heart wrenching and hard to talk about, because those are the things that really need to be said and discussed. Even though some parts concerning rape were hard to read, I think it’s very important to know about so that we can start to shed light on more and more victims. Great Article!

David Castaneda Picon

I think this was a very descriptive article with lots of information. Before this article I had little to no knowledge about the African World War. This article is great. However, it is very sad and unfortunate to read about how young girls are being raped, I can not even imagine the effect a rape have on a victim. Although this young girls want rough tough times, they managed to overcome that situation and that is really inspiring.

Samuel Vega

I was immediately struck by the title of the article “Sexual Violence as a Military Weapon.” I did not realize how the military of the Democratic Republic of Congo used mass rape to violate not only the victims; but the communities were the victims lived. Mass rape of girls, women, and often men occurred so the DNC could take control of the territories and the natural resources. The mass violation of others is so unthinkable. The personal story of Jeanne, who later called herself Jane, helps you better understand the tragedy and the immense impact the civil war of the DRC had on its people. The article discussing the City of Joy give you hope for Jane and the Congolese people.

Giselle Garcia

This article explained very well about the sexual violence in the DRC and what steps have been taken to rehabilitate victims of sexual violence. I couldn’t believe the horrible things these women had to go through and especially reading Jane’s experience was very saddening. After going through constant struggles, she was able to join the City of Joy and heal, as well as becoming an activist for her community. She is such an inspiration for others who are suffering from any harm.