“Bloody,” “horrific,” and “unbelievable,” are perhaps the best terms to use to describe July 1, 1916. Early that morning, British volunteer troops strapped their boots, gathered their gear, and loaded their rifles in preparation for what they expected to be an easy and victorious battle. This all changed as soon as the battle began. British troops lined the northern river of the Somme and prepared their first batch of 120,000 troops to take on the German line and exploit their hold on the Somme.1 This, however, was not the case. At 7:30am, the British forces charged the open land that had been berated with artillery shells. Screaming and shouting, the British troops attacked the German front, only to be met with machinegun fire and explosive shells on the German’s end. On this single day, the British suffered 57,470 casualties, of whom 19,240 were killed and 35,493 wounded, and the remaining troops taken as prisoners of war. The very first day of the Battle of the Somme was a day in history that, not only will the world will never forget, but the British will certainly never forget, as it was “etched in the British national consciousness” forever.2

In 1914, Great Britain became involved in a global war against Germany, which would cost the British countless lives. Britain’s involvement in the war was a pure result of Germany’s persistence in dismantling the French’s stronghold, as the German army targeted French regions of land through Belgian territory, and “since 1906 there had been an agreement with the French” that stated in case of “any event of war with Germany, a British Expeditionary Force of six infantry divisions and one Calvary division… would fight alongside the French,” as historian Martin Middlebrook said in his historical book over the Somme.3 With Britain knowing what they were about to enter, they needed a plan of action, but before they could do that, they needed men. Establishing a plan as to how they were going to recruit men was one of the biggest challenges that Minister of War Lord Kitchener faced at this time. He devised a plan to forge an entirely new army made up of civilians. As the British Parliament passed the Military Service Act, and drafted 500,000 men, the nation’s patriotism skyrocketed, with most of the mature men wanting to fight and contribute to their country. As historian Middlebrook wrote, so many of the men were eager to serve, “local authorities and prominent people took the initiative in sponsoring units of their own”; sponsorships that would include providing clothing, food, and pay for the men. As men from numerous cities flooded the recruitment centers, officials found it best to sort these men by district or region, with men serving alongside their lifelong friends in battle.4 These distinct city-based battalions became known as the “Pals Battalions,” since many of the men in those units were in fact pals. For about a year, Englishmen trained in France; they quickly learned the foundations of battle and how to adapt to radically different living conditions. Not only this, but they also learned the fighting strategies of the Germans. Many tactics were very much new to them, such as trench warfare, machine-gun use, and spasmodic warfare. In 1914, these newly gathered troops arrived in France and were forced to learn the ways of war relatively quickly, as they were rushed to the front within a few days of landing. In about a year, however, more men from the “New Army” had arrived and became accustomed to war more gradually than the initial troops that arrived in before them. Throughout this time, the British army had been fighting and struggling through smaller battles, until they, along with France, had devised a plan to attack the Germans and gain back territory. The British’s hope was to engage the Germans at the river Somme, push them back with infantry troops, and exploit the opening gap with cavalry men. Fate however, had other plans for these British forces.5

Leading up to the battle, much planning had been done to ensure a German defeat with a primary attack. The mistakes were made when there was no contingency plan if their initial strategy failed. British General, Sir Douglas Haig, was the one responsible for drafting the British attack on this dreadful day. He first ordered for there to be an initial 8-day barrage of missiles and cannons aimed at the German forward line. The hope was to destroy German initial defenses for the British and French infantry men, and then provide an opening for calvary troops to easily enter through and push back the German’s front in Belgium.6 This plan is what made Sir Douglas Haig so controversial in his leadership of the British troops. The controversy was mainly in his preparation and the thought process behind the plan; his military knowledge and experience itself was more than valid. Gen. Haig came to this position with previous battle experience, being an infantry commander in 1914, and eventually an army commander by the end of the year. Sir Douglas was eager to win this battle, as many claimed that he had animosity towards the French due to his attitude towards French leaders. This level of battle, however, was unlike others that Haig had participated in; in this battle, he had something to prove. This may have been what had distracted him from devising an effective plan for the Somme. In addition to this, the French troops would not be participating in the battle as much as they had initially agreed. This was because of what they had to commit to the Battle of Verdun. They were only able to pursue an 8-mile attack on the Somme, rather than the 25-mile attack they had initially committed to, which would have taken them to a meeting point with the British. As if this was not enough to burden Sir Douglas Haig, the French were also requesting more and more British troops, advising that they could only hold Verdun until July 1, and then troops would need to be sent to further defend Verdun. This information was given to Gen. Haig much later than he would have liked, considering his still relatively inexperienced troops. Despite this, Great Britain abided by the French request, and considering that the troops were already awaiting orders at the Somme, Sir Douglas Haig was forced to formulate one of the quickest battle plans of his life.7

With the soldiers arriving in Picardy north of the River Somme, many of them were already not in the best conditions. The soldiers had already been hiking for miles, in horrible heat and health conditions; many of them were feeling the shock of Mother Nature for the first time and barely able to push on. Once they arrived at the Somme, the men were dismayed at the realities of what it meant to be a soldier in the 1916. In terms of who would fight and who would work in the communications tent, men were at the mercy of their commanding officers. Officers determined who would serve on the field or the office based on skills and attributes they initially saw in the soldier. Along with the underlining fear of who would fight and who would not, historian Middlebrook pointed out that the “infantry men were also being issued their full loads of equipment” and finally realizing “the full weight of the burdens they would have to carry” into the horrors of battle.8 British troops truly did not know what to think during this time of preparation. British men were given the full weight of their gear, and saw wild rodents along the walls of their own trenches, all while simultaneously hearing artillery shells being fired into German territory. Despite these overwhelming pre-battle events, the troops of the Pals Battalion still felt confident about the outcome of this battle, as commanding officers of several companies gave their men pep talks and motivational speeches.

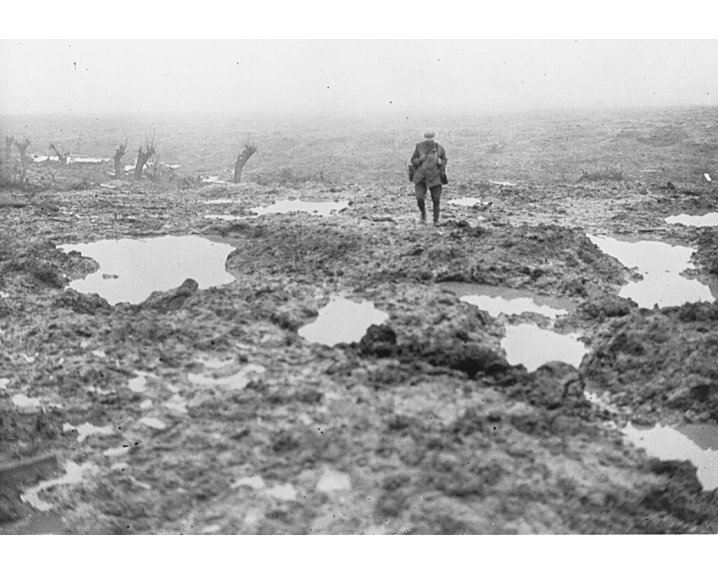

Despite the large level of confidence among the British, their preparations for battle were not as effective as they had thought. During the 8-day barrage of artillery attacks on the Germans, many had thought that the German defenses would be obliterated, if not most of the Germans being killed. However, neither of these things happened. During the 8-day bombardment, very little of the German defenses were destroyed due to the lack of strength in the offensive artillery. The only thing this week-long artillery strike did was churn up the horrid ground known as “no-man’s land.” Not only this, but after the artillery barrage, General Sir Douglas Haig held his troops from attacking the front line for an extended amount of time, allowing the German troops to ready themselves within their own trenches and prepare for battle. British troops later found out that during the 8-day bombardment, German forces had taken refuge in their deep dug-outs, meaning that, while the hail of shells were falling on the trenches above, most of the Germans and their machine-gun artillery were quite safe underground which was something that Gen. Haig and the entire British force did not anticipate.9 The British were expecting a worn and torn German front by the time they went out to fight. And that was not the case at all, and it placed the British troops under a large false sense of security.

With everything seemingly in place for the British, they began to prepare for the actual battle. The men waited, some eagerly and most fearfully, in their trenches for their commanders to give the call of attack. After what surely felt like a waiting period of several hours, 7:30am came upon the men of the Somme. This was the set time of attack for the British. British commanders sounded the attack whistles and the Pals Battalion climbed up from their tranches and began marching into “no man’s land.” During the first few minutes of the march, the battalion marched in a quiet field with almost no sound. Soldiers marching were almost disappointed by how little action there seemed to be. This feeling of disappointment was soon ended. This was the start of the one of the worst days in British history.10

This period of silence was soon ended by German bullets flying by British troops and dropping them to the ground before they even had an opportunity to lift their rifles. For twenty-six kilometers, the British troops were ordered to march and overwhelm the German defenses. This was particularly difficult, since the field of “no man’s land” was covered with dirt, artillery craters, broken limbs of trees, and barbed wire. As the British troops kept pushing forward, they noticed that it was not simply the German front they were fighting against, but also the German flank to the left of the Brit’s camp. The German’s had formed a flanking assault against their enemy, which made it even more difficult for them. Left and right, bombshells were hitting the ground and going off, along with the sounds of machinegun fire coming from unknown directions. The enemy was most certainly present for the British, but nearly invisible to their eyes; by the time they had realized where the enemy was hiding, it was far too late.11

Getting to the German front was all the British men had been hoping to do at this crucial point. Many of them saw each other die before they could even cross “no man’s land.” What had given these men hope was that once they reached the German trenches, the barbed wire and German barricades would have been destroyed by the 8-day barrage of artillery prior to the day of attack. This was at least what their generals had told them. This, however, was not the case once they advanced deep into “no-man’s-land.” While some men came across a cut or destroyed section of barbed wire, many men were met with a German defense line nearly perfectly intact after the British barrage.12 At this point in the battle nothing was going to plan, and nothing was working for the British men. While being met with so much adversity, they did their best to push forward and take what German lives they could; however, the amount of lives they took was not nearly enough compensation for the number of lives they had lost. After several hours, both sides stopped fighting for the day. While this single battle would continue for another four additional months, this single day was the day that every British solider would remember.13

Once the first day of the Battle of the Somme had concluded, many men were left questioning the planning ability of their officers, and many officers were questioning their own planning ability. After such a miserable result from a battle plan, British officers needed to gain their troops’ trust back. The trust was lost less from the fact that most of the men had died during the march into “no man’s land,” but more from the fact that the week-long artillery barrage had not “all but destroyed the German defenses.” This miscalculation had left the British troops in fear of a new plan, and would later go on to be considered the “most costly miscalculation of the Great War.”14 This single, heavily defeated day left the British generals and officers scrambling for a new and more effective plan; morale and enthusiasm can make troops dangerous. After this first day, few of the men had any kind of enthusiasm or faith in a new battle plan. For the second day of the battle, the British officers came up with a plan to attack certain sectors at different times, rather than call for a complete invasion of troops all at once, as they had tried on the first day. These kinds of strategies and effective realizations were what British leaders were realizing after the first day; however, this was all far too late for their troops’ lives.15

This battle of the Somme, to this day, has gone down in history as Britain’s greatest loss in a single battle. Once the first day had ended, the Germans allowed British troops to retrieve their dead. The total casualties for the day amounted to roughly 57,470 men either killed, wounded, or missing in action. Of the 57,470 men, 19,240 were confirmed dead, 35,493 were wounded, and the other 2,737 men were never found dead or alive. The most disappointing aspect of the battle was not the amount of losses the British endured, but the little ground gained for such a tremendous loss. Despite the near 60,000 casualty list, only around 3 1/2 miles in depth were gained.16

So much was lost, and so little was gained for the British army on July 1, 1916. Many speculate as to why the battle plan failed so miserably. Was it because of improper planning? Miscalculations? Pure bad luck? No one can contest to the fact that this event was horrific and useless when compared to the amount of gain the British army obtained. While many may not be of European or British descent, many should still know and remember this first day at the Battle of the Somme, because many men gave their lives before being able to return a single bullet. It is for this reason that people around the world should at least remember them in their prayers and respect their taken lives.

- Seth Feldman, “Battle of the Somme: What the audience saw,” Revue Canadienne d’Études Cinématographiques / Canadian Journal of Film Studies 27, no. 2 (2018): 2–3. ↵

- Edward M. Spiers, “Yorkshire and the First Day of the Somme,” Northern History 53, no. 2 (September 2016): 1-1, https://doi.org/10.1080/0078172X.2016.1195601. ↵

- Martin Middlebrook, First Day on The Somme (New York: W.W. Norton & Company Inc, 1972), 21. ↵

- Martin Middlebrook, First Day on The Somme (New York: W.W. Norton & Company Inc, 1972), 20-22. ↵

- Martin Middlebrook, First Day on The Somme (New York: W.W. Norton & Company Inc, 1972), 25, 26, 69. ↵

- Martin Middlebrook, First Day on The Somme (New York: W.W. Norton & Company Inc, 1972), 67-69. ↵

- Martin Middlebrook, First Day on The Somme (New York: W.W. Norton & Company Inc, 1972), 68. ↵

- Martin Middlebrook, First Day on The Somme (New York: W.W. Norton & Company Inc, 1972), 94-95. ↵

- Trevor Wilson and Robin Prior, “Summing up the Somme,” History Today 41 (November 1991): 38. ↵

- Martin Middlebrook, First Day on The Somme (New York: W.W. Norton & Company Inc, 1972), 121-122. ↵

- Trevor Wilson and Robin Prior, “Summing up the Somme,” History Today 41 (November 1991): 39. ↵

- Trevor Wilson and Robin Prior, “Summing up the Somme,” History Today 41 (November 1991): 39. ↵

- Martin Middlebrook, First Day on The Somme (New York: W.W. Norton & Company Inc, 1972), 130-332. ↵

- Seth Feldman, “Battle of the Somme: What the audience saw,” Revue Canadienne d’Études Cinématographiques / Canadian Journal of Film Studies 27, no. 2 (2018): 1–3. ↵

- Martin Middlebrook, First Day on The Somme (New York: W.W. Norton & Company Inc, 1972), 159-161. ↵

- Edward M. Spiers, “Yorkshire and the First Day of the Somme,” Northern History 53, no. 2 (September 2016): 249–66, https://doi.org/10.1080/0078172X.2016.1195601. ↵

8 comments

Muhammad Hammad Zafar

I like the article but what I like the most was about the author.

Secondly, it is full of descriptive writing and pictures that increase the understanding of the author’s idea.

After reading it, we can clearly understand that we have to think before we take any steps. As we can see that so many lives were lost and I was very sad while reading it.

But I would once again say that the pictures and descriptions were amazing.

Courtney Mcclellan

The opening of your article is amazing, it is very well set up and it grabs the readers attention. Its really sad that they threw barley taught men unto battle because of an agreement with France and in a war that they were not apart of. It saddens me to thunk that men, who were already not in the best condition, were thrown into battle by a general who had something to prove.

Franchesca Tinacba

Such an awesome article to read! I have always been interested in stories dealing with the history of the military thanks to being a military brat, so this definitely peaked my interest when finding an article to read. I had really no idea this happened, but when I was reading this, it really saddened me realizing how many lives were lost. I think stories like this help people realize how important planning and calculating every move really is.

Seth Roen

Great article of one of the bloodiest battles of the First Great War. It is rather sad how many men lost their lives during the Battle of the Somme. Despite their training, they were still underprepared for the hell of the First Great War. It almost seems like the British have the habit of not being prepared for war with peers. Due to them fighting in the colonies in the decades prior.

Jace Nicolet

I like this article for many reasons. One of the reasons is that it captures my interest with the pictures, almost putting me in the setting with them,. It also had pictures of the general in uniform which I thought was really cool. There is also very descriptive writing, word, and pictures included hat highlight the seriousness of the subject,

Javier Oblitas

The article was very masterfully written, it held interest while also continuing to tell the facts in detail. I hadn’t even remembered about learning of the Battle of Somme until I read this article and got a even deeper insight into it and the implications of it. I had never known just how gruesome and destructive World War 1 had been. This battle serves as a potential what not to do when it comes to military strategizing, the pal battalion seemed like it had been a good idea.

Samuel Vega

Andrew, I also enjoy Military History and found interesting points in your article that I was not familiar with. You discussed strong reasons for this battle being the “most costly miscalculation of the Great War.” One of the points was the lack of training for the Pals Battalions. The young recruits were willing to fight for England but were unprepared. Another point was the poor strategy that was executed by General Sir Douglas Haig. The offensive artillery did not cause any substantial to the Germans, yet the English lost more than 19,000 men and had more than 35,000 that were wounded. This battle is good to evaluate for the military strategy and the impact that it had.

Ben Kruck

This article was nice to read! I’ve always been interested in this topic, so this piqued my interest when I saw it. I didn’t realize the Battle of Somme was that catastrophic for the British, and it now reminds me how destructive World War 1 actually was. After reading the article, I can assume that it may have been a mixture of bud luck, miscalculations, and improper planning. All of that can definitely lead to lower morale.