“Remember us children and we will remember you our whole life”

-ten year old Helma Lurch 1

Near the end of World War II, the Allied Powers had to decide what to do with Germany and its largest city, Berlin. At the Potsdam Conference in July 1945, it was decided that Germany would be divided into four sectors: France in the southwest, Britain in the northwest, the United States in the south, and the Soviet Union in the east. Lying completely within the Soviet-controlled east sector, Berlin was also split into four sectors among the same countries. Berlin was to be ruled by representatives of all four countries, each one with veto power, and all decisions had to be unanimous. It was the first time a nation had been taken over for the sole purpose of creating a democracy.2

Three years later, in 1948, living conditions in Berlin had not improved since the war ended. Berliners were still starving and living in poverty. Most of the people were unemployed and dependent on the food and supplies brought in by the controlling governments for survival. Each power was responsible for the Berliners in their sector. The three western powers did not feed the Berliners out of compassion, but rather to keep them from fleeing to the Soviet sector that fed their people better rations.3

Meanwhile, the Soviets were busy taking control of all Europe east of the Elbe River, with the exception of the three sectors of Berlin that were controlled by France, Britain, and the United States. By March 1948, the Soviets in Berlin began kidnapping Berliners that entered the Soviet sector for one day, forcing them to do hard labor, and then releasing them. The Soviet Army began to block roads leading out of the city for short intervals to create problems for all people trying to leave the city.4 Most troublesome to the western powers was the build-up of Soviet troops just outside of Berlin.5 In April, the Soviets issued new regulations that required all Western military personnel traveling into Berlin to carry permits and be subject to inspection. The Soviets also limited the travel of supply trains to one each day. At this point General Lusius Clay, the United States Army commander in Berlin, requested air support from Rhein-Mein Air Base in West Germany to Tempelhof Air Base in Berlin, in order to provide support for the roughly 10,000 US troops in Berlin. After seeing the successful supplying of the US troops by the airlift, the Soviets lifted their restrictions. This episode was but a prelude to a much larger event.6

On June 19, 1948, the Deutschmark became the currency of West Germany, but not in Berlin. In response, the Soviets allowed only one train each day to enter Berlin and then they closed the bridge over the Elbe River, completely cutting off travel by road into Berlin. By 21 June, the Soviets introduced their currency in East Germany, but not in Berlin. Eventually the four governing powers of Berlin agreed to use the Deutschmark in the western sectors of Berlin and the Soviet currency in eastern sector of Berlin.7 The division of Berlin had begun.

Shortly before midnight on June 23, 1948, the Soviet Army issued an order stopping all passenger and cargo traffic into and out of Berlin due to “technical difficulties.”8 All of a sudden the 31 million pounds of supplies brought in everyday to maintain the 2.25 million people in the western sectors of Berlin stopped. Soviets also cut off the power lines supplying the western sector with electricity.9 The Soviets wanted Berlin and hoped that the United States, France, and Britain would surrender West Berlin and leave quickly.

Three days into the blockade, General Clay realized that air travel was the only way to bring supplies to the West Berliners, so he made the arrangements to fly supplies from Rhein-Mein into Tempelhof once again. Only this time, the British Army was also flying in supplies. General Clay knew that the airlift could only be temporary; he simply wanted to keep the supplies coming into Berlin until there was time to evacuate all the US soldiers and their families. A call soon went out requesting all available C-54s be sent to Rhein-Mein to bring in the 2 million pounds of supplies needed each day.10

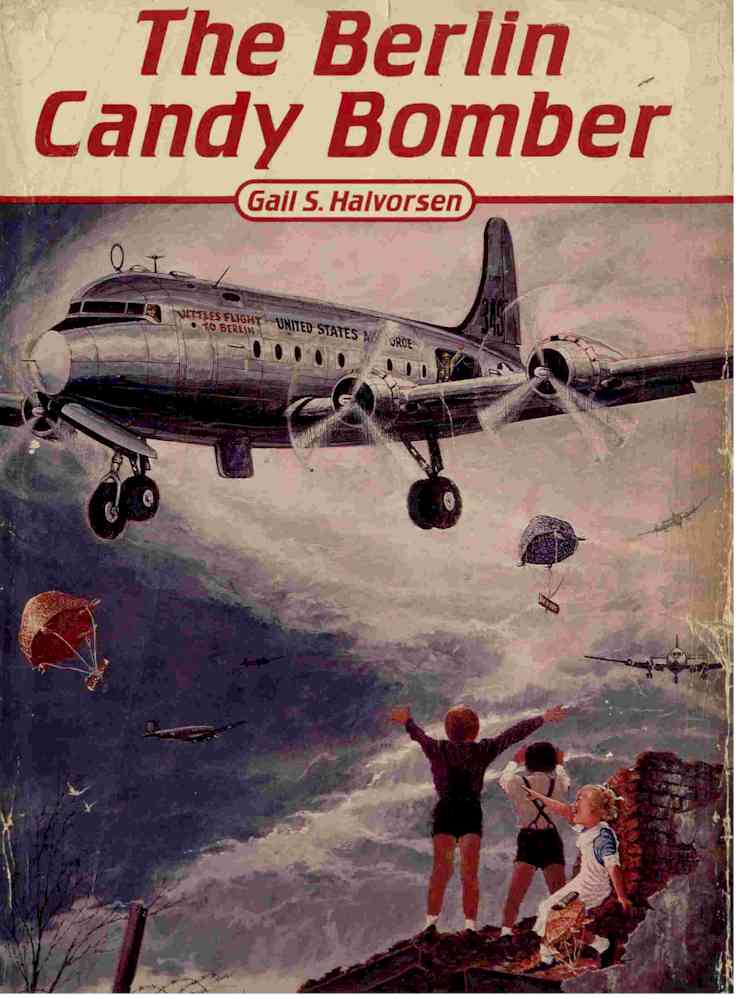

Lieutenant Gail Halverson was stationed in Alabama when he heard of the need for C-54 pilots for an airlift. He was not chosen in the initial round of assignments, but he volunteered to take the place of a friend whose wife had just given birth to twins. Lt. Halverson had a bad cold at the time he left for his duty, so he packed all the handkerchiefs he could find. Upon arriving at Rhein-Mein, Lt. Halverson was partnered with Captain John Pickering and Sergeant Herschel Elkins to create their flight crew for the entirety of their time at Rhein-Mein.11

Several of the airmen assigned to the airlift had been the same airmen dropping bombs on Berlin three years earlier. They were conflicted about saving the same people that they were once ordered to kill. Many felt that saving the children made it different. Others tried to waste time in order to limit the number of flights they were able to make each day. Most of the Berliners thought the United States was simply trying to show their strength to the Soviets and did not care about the survival of the Berliners. For the most part, the Berliners did not care who brought them the food; they simply wanted to survive.12 The Air Force thought the mission was doomed to fail; the military was for protection, not humanitarian aid.13

By late July, Lt. Halverson thought the mission would soon be over and he wanted to see the city of Berlin before he was sent back home. One day after landing at Tempelhof, he walked down to the end of the runway to take pictures. He noticed several children standing around and began talking with them. Before walking away, he gave the children two sticks of gum he had in his pocket. The children split the gum into tiny pieces in order to share this new treat with each other. Lt. Halverson told the children he would drop candy to them when he returned. He told them to watch for the plane that wiggled its wings so they would know it was him.14

Lt. Halverson told his crew that he planned to drop candy down to the children the next day, so the three of them used up their weekly rations of candy and gum at the base store and set about figuring out how to drop the candy. It was then that all those handkerchiefs would serve a special purpose. The three of them spent the night tying candy to the handkerchiefs to form small parachutes that could be thrown out of the plane.15 The next day, as their plane approached Tempelhof, the children were gathered in the same place. Upon seeing them, Lt. Halverson wiggled the plane’s wings, and Sgt. Elkins dumped the candy parachutes out. Because of the layout of the buildings around the runway, they had no way of seeing whether the children had gotten the candy.16 However, in the days following that first drop, all the airlift pilots noticed an increase in the number of children gathered outside the base waving at all the planes that flew overhead. The trio repeated the candy drops two more times over the next two weeks.17

By early August, it was clear that the airlift was struggling to deliver the massive amount of supplies needed each day for the city. The city needed eight million pounds of supplies each day and they were averaging 1.6 million pounds each day.18 Bill Turner was sent in to reorganize the airlift and make it successful. Turner had a new plan that made the airlift more efficient by having planes landing or taking off every ninety seconds from Tempelhof. He brought in a food truck run by beautiful young Berlin girls to keep the flight crews near their planes and ready to go as soon as the planes were unloaded. Turner, General Clay, and President Truman all knew that the purpose of the airlift was not just to feed the Berliners, but to inspire them to stay strong in the face of the Soviet psychological warfare that played out in their streets on a daily basis.19

Three months into the airlift, most Berliners were still skeptical of the powers controlling them. Soviets had been trying to get the Berliners living in the western sectors to move to the eastern sector by offering new and better food rations that included fresh meat and produce. A separate police force was also formed in the western sector that further broke the city in two.20 There was rioting in Postdamer Platz in the middle of Berlin that ended when the US Army started patrolling the area. The next day signs were posted saying “You are leaving the American sector” and a line was painted down on the cobblestones. On August 21, 1948, Berlin became two cities.21

The candy drops continued until one foggy day when Lt. Halverson walked into the control office at Tempelhof to get a weather report. He noticed several letters on the desk written to “Onkel Wackelflugel” (Uncle Wiggly Wings) and “Schokoladen Flieger” (Chocolate Flier).22 The bonds that the candy drops formed for the children of Berlin would last into adulthood.23 It was not until the end of August when a reporter, writing a story about the airlift, was standing with the children at the end of the runway, was hit on the head by a candy bomb, that the story was made public. Lt. Halverson expected a court martial, and was completely surprised to learn that the airlift officials encouraged him to continue his drops. Turner knew that these candy drops were a powerful symbol in the war for the people of Berlin, and he immediately put Lt. Halverson in front of the press to promote his candy bombing.24

The world loved the story of the candy bombs, and donations of candy and material for parachutes came in from all over. The city of Chicopee, MA was home to Westover Air Base, which served as the launch base for all supplies going to the airlift. The children of Chicopee spent many hours after school and on Saturday mornings making parachutes and boxing them for delivery by the candy bombers.25 All the major candy companies in the United States worked with each other to donate over 13,000 pounds of candy that arrived by December 1948, just in time to be used for Christmas parties for the children held throughout the city.26

As the donations of candy increased, Turner ordered more planes to begin dropping candy bombs throughout various parts of the city. Parents and children across Berlin began writing letters to Lt. Halverson thanking him for the gifts, requesting special drops, and even sending small gifts of thanks. By that winter, the airlift had dropped over 36,000 pounds of candy tied to over 100,000 parachutes.27 The Soviets had learned of the candy drops, and did not like it; they issued an order that any candy dropped in their sector would be taken as an act of war.28

Winters in Berlin often bring fog so thick that planes cannot land. This winter of 1948-49 was no different. By November, the weather was so bad that the airlift was grounded more days than it flew. Supplies were limited, and people in Berlin were starving and freezing. Westinghouse created special lights that were sent to Tempelhof to allow the pilots to see the runways in the fog. These lights are now standard at all airports.29 It was February before the airlift was able to return to its previous delivery levels.

Lt. Halverson flew a special flight on Christmas Eve in 1948, dropping over 4000 candy bombs all over the city for children to wake up and find in the morning.30 He flew his last flight of the airlift in January 1949 before being sent back home. In all, Lt. Halverson dropped over 90,000 parachutes over the city during his tour of duty. He made arrangements for the candy bombing to continue after he left. In March, the delivery of the candy was taken over by welfare agencies, hospitals, and youth centers, which delivered approximately six million pounds of candy each month for the remainder of the airlift.31

The Soviets lifted the blockade on May 12, 1949, 321 days after it started. The Soviets were defeated and the people of Berlin celebrated for days. Electricity returned to the city as well as cars and trains from the west.32 Even so, the airlift continued until September to build up a stockpile of supplies for the city just in case it was ever needed again. More than 277,000 flights delivered over 4.6 billion pounds of food and supplies over the fifteen-month airlift. It remains the largest operation of its kind. Through it all, only seventy-one airmen from both British and US air forces lost their lives to save the city of Berlin.33

The purpose of the Soviet blockade of Berlin was to break down the people of West Berlin and make them align with the Soviets. The Soviets knew that hunger was not enough; the people had to feel absolute despair in order for the blockade to be successful. Many times, the Soviets expected the Berliners to give up, but instead, the people began to value democracy, the values of the nations supplying them with food. The candy drops had been the spark that changed the mindset of the West Berliners who saw the gift of candy to children simply as kindness with no ulterior motive. The noise of the planes constantly flying over head became the life-line for the people of Berlin, and the candy bombers became the new face of the American soldier.34

To protect themselves from potential blockades, West Berlin continued to maintain its stockpile of food and supplies. They had stored 132 million pounds of wheat, 52 million pounds of canned meat, 15 million pounds of butter, 11 million pounds of sardines, and 18 million rolls of toilet paper. On October 3, 1990, the Berlin Wall came down and the people of West Berlin no longer lived with the fear of the Soviets. No longer needing the stockpile, the people of West Berlin delivered their stockpile to the people of East Berlin, who were starving and lacking food and basic necessities.35

- Andrei Cherney, The Candy Bombers (New York: Putman, 2008), 411. ↵

- Andrei Cherney, The Candy Bombers (New York: Putman, 2008), 124. ↵

- Andrei Cherney, The Candy Bombers (New York: Putman, 2008), 126-127. ↵

- Andrei Cherney, The Candy Bombers (New York: Putman, 2008), 184. ↵

- Andrei Cherney, The Candy Bombers (New York: Putman, 2008), 208-209. ↵

- Andrei Cherney, The Candy Bombers (New York: Putman, 2008), 220-222. ↵

- Andrei Cherney, The Candy Bombers (New York: Putman, 2008), 235-240. ↵

- Andrei Cherney, The Candy Bombers (New York: Putman, 2008), 241. ↵

- Andrei Cherney, The Candy Bombers (New York: Putman, 2008), 241-242. ↵

- Andrei Cherney, The Candy Bombers (New York: Putman, 2008), 252-258. ↵

- Andrei Cherney, The Candy Bombers (New York: Putman, 2008), 267-268. ↵

- Andrei Cherney, The Candy Bombers (New York: Putman, 2008), 279-280. ↵

- Andrei Cherney, The Candy Bombers (New York: Putman, 2008), 290-291. ↵

- Andrei Cherney, The Candy Bombers (New York: Putman, 2008), 297-300. ↵

- Andrei Cherney, The Candy Bombers (New York: Putman, 2008), 297-300. ↵

- Andrei Cherney, The Candy Bombers (New York: Putman, 2008), 297-300. ↵

- Andrei Cherney, The Candy Bombers (New York: Putman, 2008), 349-350. ↵

- Andrei Cherney, The Candy Bombers (New York: Putman, 2008), 280-284. ↵

- Andrei Cherney, The Candy Bombers (New York: Putman, 2008), 340-348. ↵

- Andrei Cherney, The Candy Bombers (New York: Putman, 2008), 342-345. ↵

- Andrei Cherney, The Candy Bombers (New York: Putman, 2008), 353-354. ↵

- Andrei Cherney, The Candy Bombers (New York: Putman, 2008), 336-337. ↵

- Peter Grier, “Halverson: Candy Bomber, Engineer, Unofficial Ambassador,” Air Force Magazine (March 2013): 64-68. ↵

- Andrei Cherney, The Candy Bombers (New York: Putman, 2008), 351-353. ↵

- Andrei Cherney, The Candy Bombers (New York: Putman, 2008), 409-411. ↵

- Andrei Cherney, The Candy Bombers (New York: Putman, 2008), 484. ↵

- Andrei Cherney, The Candy Bombers (New York: Putman, 2008), 409-411. ↵

- Andrei Cherney, The Candy Bombers (New York: Putman, 2008), 445. ↵

- Andrei Cherney, The Candy Bombers (New York: Putman, 2008), 462-426. ↵

- Andrei Cherney, The Candy Bombers (New York: Putman, 2008), 495-496. ↵

- Andrei Cherney, The Candy Bombers (New York: Putman, 2008), 505-520. ↵

- Andrei Cherney, The Candy Bombers (New York: Putman, 2008), 526-532. ↵

- Andrei Cherney, The Candy Bombers (New York: Putman, 2008), 543. ↵

- Andrei Cherney, The Candy Bombers (New York: Putman, 2008), 470-475. ↵

- Andrei Cherney, The Candy Bombers (New York: Putman, 2008), 549-550. ↵

92 comments

Paula Ferradas Hiraoka

This was an excellent and well-written article! I’ve never managed to hear about those kinds of aircrafts, but after this article I learned a lot about this certain period of time and actions. I feel this article presents the best information regarding this story, and does an excellent job of setting the scene, making the reader aware of the times and the situation respecting history.

Overall, amazing work and incredible article!

Alex Trevino

This article is presents a classic story that many have heard of, and introduces what most do not know regarding the subject. I for one, love such stories of hope in times of hardships, such as that of the soccer game during the battles of the trenches. I feel this article presents the best information regarding this story, and does and excellent job of setting the scene, so the reader knows exactly where and when we are.

Elizabeth Saxon

I really liked this article because it describes all the hard times the people of berlin were faced with poverty and the end of the war. LT. Halverson created something exciting for the community and allowed people to forget about all their struggles with the dropping of the candy. It excited me knowing that these citizens of Germany had something to look forward to in spite of all that they had been through.

Luis Molina Lucio

This is a very engaging article, especially the title. I was very confused on why the name had “Candy Bombers” in it. While reading the article through the end when the pilots who dropped the candy were introduced then it finally clicked what the Candy Bombers meant. Kids got to be kids even if it was for a few seconds with a few pieces of candy and I really respect those pilots who took the initiative to give kids the right to be kids. Overall, a great article which I could even take a nice message from.

Jacob Galan

This was a heartfelt article knowing that pieces of candy united the people on the soviet side of the city of Berlin. What I found joyful about this is that when Lt. Halverson started to provide the kids gum and would give a signal to them on what plane was his I loved at first it was a few kids and then it turned into a group of kids. At the same time, it is sad that they were starve to death and they enjoy the few rations they could have got from those drops.

Sara Davila

This article really opened my eyes to what it is like to be living in a city controlled by war and government. It is incredible what Berlin had to go through during the end of World War II and the effects it had on the community being divided In four territories. It is crazy how candy can be the light that shines through this time. I am glad so many people were able to help make the children of Berlin feel better in such dark times.

Velma Castellanos

I loved this article because it showed that you can make other happy with the simplest of things. The article has a good description and detail on the candy bombing, I think it was very sweet for these soldiers to do something like this. I also enjoyed your image of the letter from a child. Overall, this was a great article and you did a good job!!

Nydia Ramirez

I gained a lot of new insight and knowledge from reading this article. The importance of the topic and material covered in the article is massive. It unveiled a lot of small details on the Berlin Airlift I had no idea existed. I admired the specificity of facts in this article and how it ended with the blockade being lifted. The journey the author took us on was completed seamlessly. I also admired the use of the once source. It means the author really took the time to understand the material.

Christopher Hohman

Nice article! It is a awesome that the American soldiers did something so kind for the children of West Berlin. Those initial post war years when Europe was largely still devastated from the war and the people of Berlin had to be lightened by something. In this case it was candy and the supplies airlifted to the people of West Berlin. It is indeed true that these children must have remembered these men for the rest of their lives. The candy airdrops were acts of kindness. The children did not need candy to survive, but the Americans made sure they got some just because they were kind. Actions like this helped turn public opinion in favor of the Western Allies! It was interesting also that the West Berliners maintained a stockpile of supplies until the fall of the Berlin Wall. I am also happy to hear that they shared their supplies with the impoverished citizens of East Berlin.

Hali Garcia

This is such a nice and uplifting article. It is nice to read stories about how while there is a war going on, there are also acts of kindness too. These candy bombs brought hope and joy to the children of Berlin. What struck me the most was how the people would donate candy and materials for the candy bombs and the children in the U.S. would help make boxes and parachutes for the candy.