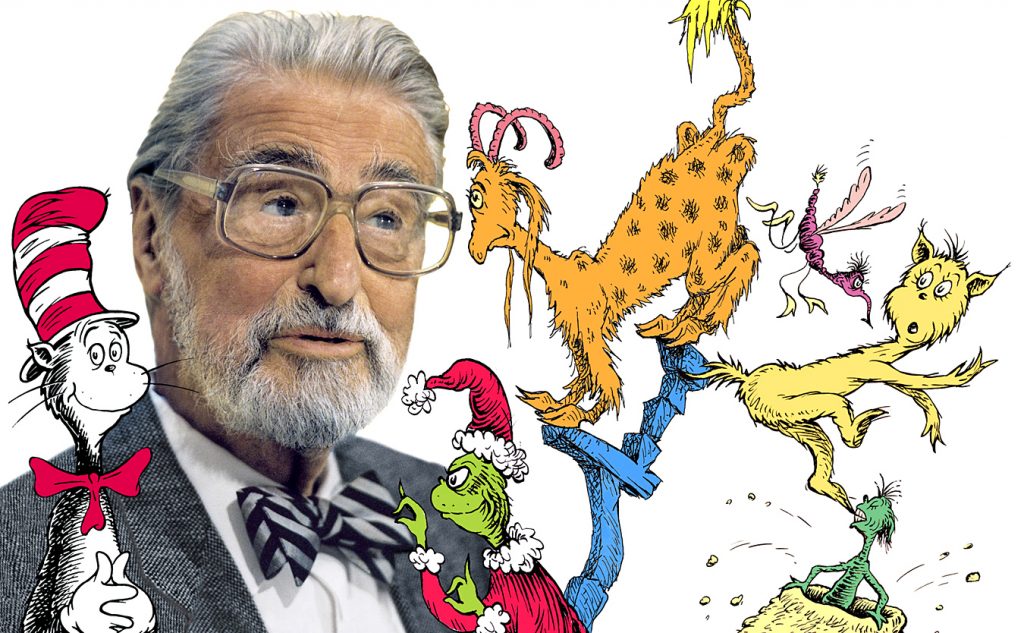

Theodor Geisel, beloved children’s author, had a life before he put the hat on the cat. Born March 2, 1904, in Springfield, Massachusetts, Geisel was the only son of German-born immigrants. He spent a normal childhood with his sister and parents, before going to college to become a teacher. Geisel dropped out of college shortly before completing his doctorate in literature. He would eventually turn his almost doctorate and his mother’s maiden name into his now famous pen name, Dr. Seuss.1

In 1927, Geisel decided to turn his passion for drawing and writing into a career in advertising. One of his early successes in advertising was his drawing for Flit insecticide, whose mascot looked very similar to the cat that would eventually wear a striped hat.2 He later created an entire campaign for Essomarine Oil, a division of Standard Oil, called Seuss Navy, in which he designed certificates of membership, pamphlets, and even ashtrays and cocktail glasses that were passed out at trade shows. The Seuss Navy ads ran from 1936 to 1941, and contained many of the sea creatures that would later appear in his books.3 Geisel used many of his made up creatures in various ad campaigns and was the first person to use humor to sell products, altering the advertising industry.4

In 1941, Geisel left advertising to work as a political cartoonist for liberal New York newspaper PM. He drew over 4oo cartoons targeting such topics as isolationism, antisemitism, and racism. He routinely mocked Hitler and Mussolini, but he had a particular flair for attacking American nationalism as well. Believing that the American Nationalist Movement was just another form of fascism, Geisel made Charles Lindbergh a frequent subject of his cartoons.5 After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Geisel began to use his cartoons to support the war against Japan. He drew cartoons that “depicted Hideki Tojo, the Prime Minister and Supreme Military Leader of Japan, as an ugly stereotype, with squinting eyes and a sneering grin.”6 Geisel was in support of Japanese internment camps and drew several cartoons about them.

It can be hard to imagine that Dr. Seuss could be a racist in his depiction of Asians, but he later admitted that this was exactly the case. At the time, PM did not receive one letter of complaint about Geisel’s stereotypical depiction of Asians, although they received many letters when Geisel mocked the German dachshund, which was popular among American dog owners. Dr. Seuss later said that his 1954 book, “Horton Hears a Who,” written after a trip to Japan and dedicated to a Japanese friend, is meant to be an apology to the Japanese people for his depictions of them during World War II. In the 1980’s, Geisel looked through all his children’s books and removed anything he felt was racist, changing them for any future publication.7

Geisel’s political cartoons ended when he joined the Army in 1943. The now Captain Geisel was assigned to a unit that made training films for the Army, working with the likes of Stan Lee (creator of super heroes) and Chuck Jones (creator of the Road Runner and Wile E. Coyote).8 Geisel and Jones would become life long friends and would work together on various projects, including the animated “How the Grinch Stole Christmas,” which is still shown every year on television.

Geisel’s first children’s book was “And to Think I Saw It on Mulberry Street,” and was published in 1937. However, his writing career almost never happened. The book had been turned down by 27 publishers and Geisel was ready to give up the idea of becoming a children’s author when he ran into an old college friend while walking down the street. His friend had recently become an editor at Vanguard Press and asked Geisel to send him the book so he could show his boss. Geisel would later say in interviews that it was pure luck that he walked down that side of the street that day.9

Dr. Seuss later claimed that he did not like to write books that had a moral or ethical lesson, because children could see a lesson coming and would not want to read the book.10 However, all of Geisel’s books, except his Beginner Books, contained lessons of some sort. Dr. Seuss wrote books with lessons on environmentalism, racial equality, the pointlessness of the arms race, materialism, and respect, just to name a few. He was one of the first children’s authors to write books for children with the respect and care typically reserved for adult literature.11

Dr. Seuss died on September 24, 1991 at his home. He was asked shortly before he passed away to leave a message for children. He wrote “The best slogan I can think of to leave the kids of the U.S.A. would be ‘We can…and we’ve got to…do better than this.’ He then crossed out ‘the kids of.'”12 Dr. Seuss left a legacy of children’s literature that will not soon be forgotten, but he did more than that; Dr. Seuss taught children to think.

- Janet Schulman and Cathy Goldsmith, Your Favorite Seuss (New York: Random House, 2004), 6. ↵

- Louis Menand, “Cat People,” The New Yorker (December 2002). ↵

- Janet Schulman and Cathy Goldsmith, Your Favorite Seuss (New York: Random House, 2004), 55. ↵

- Janet Schulman and Cathy Goldsmith, Your Favorite Seuss (New York: Random House, 2004), 117. ↵

- Sophie Gilbert, “The Complicated Relevance of Dr. Seuss’s Political Cartoons,” The Atlantic (January 2017). ↵

- Sophie Gilbert, “The Complicated Relevance of Dr. Seuss’s Political Cartoons,” The Atlantic (January 2017). ↵

- Sophie Gilbert, “The Complicated Relevance of Dr. Seuss’s Political Cartoons,” The Atlantic (January 2017). ↵

- Janet Schulman and Cathy Goldsmith, Your Favorite Seuss (New York: Random House, 2004), 9. ↵

- Louis Menand, “Cat People,” The New Yorker (December 2002). ↵

- Janet Schulman and Cathy Goldsmith, Your Favorite Seuss (New York: Random House, 2004), 190. ↵

- Janet Schulman and Cathy Goldsmith, Your Favorite Seuss (New York: Random House, 2004), 84. ↵

- Janet Schulman and Cathy Goldsmith, Your Favorite Seuss (New York: Random House, 2004), 190. ↵

125 comments

Osman Rodriguez

Dr. Seuss definitely left his mark on children’s literature. I remember way back when, a time where your elementary teachers would read his books to the class, or when you were able to read the books yourself. I also remember watching the inspired movies and animated shorts. Reading the article brought back all those memories, and definitely taught me some things about him as well. I didn’t know he made ad’s for companies or that he worked for a newspaper making political cartoons. What i found very peculiar was when he became Captain Geisel, definitely an interesting fact.

Eduardo Foster

I have not been that much of a fan of Dr. Seuss. The story background about him doing cartoons is actually interesting. After his visit of Japan it reflects him as a very good person. I think that he’s historical background provided good motivation to write his books. Even though it’s also inspirational his last words and tells you what Dr. Seuss encourage childs for the future.

Andrew Rodriguez

I had no idea the Dr. Seuss was in the advertising business, how his drawings on the advertisements resembled the famous character of his cat in the hat. Astonishing knowing that he dropped out of college while being so close to achieving his doctorates. The article was very entertaining to read, about a man who has a giant footprint on the youth for a very long time. It was very well written and the research as well. It was fun to know that his original last name was not Seuss but Geisel’s, there is a fun fact I can say to people.

Tyler Bradford

As a kid who grew up reading the books of Dr. Seuss, I was very surprised from reading this article. I had no idea of the whole backstory behind all of Dr. Seuss’ cartoons and stories being based off of social and political views targeting the topics of isolationism, antisemitism, and racism. When hearing the name Dr. Seuss, you don’t usually associate those topics with him or at least I don’t. So it was just a little shocking to know that his cartoons held a more serious purpose in the fact that they touch on controversial issues while not appearing so due to their animated appearance.

Soteria banks

I was never a fan of Dr. Seuss honestly, maybe because living in Detroit , we really never had the resources for his books. But reading , and informing me about his background . I felt better about him. I really liked how he had a change of heart , about the Japanese, I think people always think about the lesson they learn from his books but I feel like he probably learned more while going through the struggles for writing and drawing his books, I think that’s more interesting , than his books .

Carlos Aparicio

As one of my favorite authors as a child, I never knew that Suess was not his last name. It amazes me how many changes of his career he had to go through to get where he was, a children’s author. I believe that his background on isolationism, antisemitism, and even racism eventually led up to his creative juices to write the stories that he published. I am confused about how Dr. Seuss primarily wanted to write books with no life lessons when some of his stories did. Overall, very interesting article!

Lauryn Hyde

Dr. Seuss has become such an icon in children’s book and was definitely part of my childhood. Learning about the start of his cartoon making and how it was political and not the lighthearted kids book we know to day was very interesting to me. The most interesting thing I learned in the article is how Dr. Seuss would add subtle meaning within in his children’s books, I connected this right away to one of my favorite Dr. Seuss books “The Lorax”

Samuel Stallcup

Like many American children, I was a fan of Dr. Seuss’s books, such as “Green Eggs and Ham,” “Horton Hears a Who,” and others. I was unaware that he had quite the political career prior to being a children’s writer. The few cartoons that were present in the article were cute. I was also unaware of the time he spent with Stan Lee and Chuck Jones.

Belene Cuellar

My whole childhood was spent at the library or at home reading Dr. Seuss books. I never quite looked back into his life to see what he did before he started writing children’s books. It was quite shocking to find out his views on Asians and I’m a bit disappointed in him. Nonetheless this article was very informative and it caught my attention from the first sentence.

Alejandra Chavez

I am in complete awe as I type this comment. So much new information I would have never suspected after going through my childhood completely appreciative of an author who I have now come to find out was a soldier, college drop out, and a racist. I am utterly shocked to find out that his name isn’t Seuss at all but Theodor Geisel. As someone who hopes to serve her country and to be stationed in Germany, I am happy to have hopes to one day relate to an author who impacted my early years. Apart from awe, I am happy that even though he was a racist, he was mature enough to identify his ways and change them- hence the “Horton Hears a Who” story. I am very pleased with the way this article was written. It made me excited to write this comment.