It was Wednesday July 12, 1995. The time was 3:30 pm. The daily heat advisories were given out by the National Weather Service office in Romeoville but they were nothing out of the ordinary. With the temperature being 97 degrees and no serious call to action statement from authorities, life in Chicago went on as usual. At Comiskey Park, the Chicago White Sox’s were set to play the Milwaukee Brewers. Across the city, Mayor Richard M. Daley was speaking at a ribbon-cutting ceremony for the grand reopening of Navy Pier. But as time ticked on, the grounds of Chicago would become a giant blast furnace with the lives of 739 people falling to this wrath.1

Thursday July 13. Temperatures have now hit 104 to 106 and those on the streets were reported to be “walking in a daze.” Weather authorities have been well aware of the heat but have written it off simply because the summers in Chicago are usually very hot. The forecast was monitored but not seen as an immediate threat, so therefore no one really changed what they did. Lake Michigan and community pools were packed with crowds and there were over 3,000 fire hydrants that had been illegally opened trying to combat the heat. Despite these efforts, people have begun to suffer from heat-related problems and were growing concern for their loved ones. 911 operators were being flooded with a staggering 16,727 number of calls complaining about the heat. While paramedics were being called all over the city, emergency departments and waiting rooms were filling up rapidly, causing workers to operate like a pit crew in Nascar. As they began to enter “crisis mode,” panic was on the verge of ensuing, the authorities were still not taking it too seriously.2

Friday July 14. As the heat spreads, City Hall officials were again not aware of the disaster that was about to unfold. Emergency rooms were beginning to deny new patients as across the city over 49,000 residents have lost power, deeming air conditioning and other methods of cooling off useless. Mayor Daley’s attitude now was very nonchalant towards the heat, because extreme weather is common in Chicago; however, numerous bodies were dropping in districts that were isolated from the main center of the city. The Daley administration was completely neglecting the lower income neighborhoods as people were dying in large numbers. Neighbors were calling authorities to come check in on the elderly because there was no one going to check on them and give them the help they could not get for themselves. Because many victims were not getting the attention they deserve from the Daley administration, their bodies were laying dead in their own homes and no one even knew it. As the day ended, the city’s medical examiner’s office had over forty cases for the next day alone, which never had that many cases for one day in their history.3

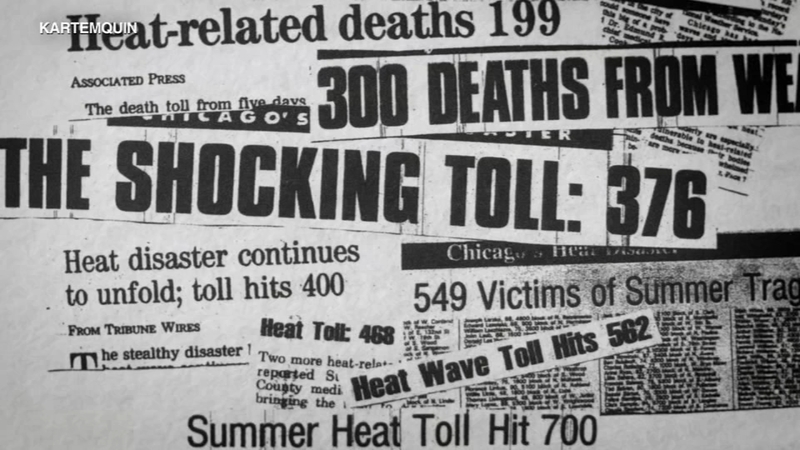

Saturday July 15. The Last Day. Temperatures now were near triple digits and the humidity was steadily high. Deputy Chief of Staff Sarah Pang received a call demanding an emergency City Hall meeting to figure out what was going on and what plans needed to be taken. However, there was no plan because no one in that department understood how dangerous heat was or could be. They were used to snow and how dangerous extreme cold could be but they had never seen a disaster like this one ever, so they did not know what to do or who to rely on. Many politicians, chiefs in offices, and other authorities within the city were not fully aware of the number of bodies or the transportation methods being taken because everyone and everything was scurrying all at once. While the mayor was vacationing in Grand Beach, Michigan, health department officials had declared a citywide heat emergency with all 56 ambulances and 600 paramedics being called to service. Trucks, refrigerators filled with decomposing bodies, and medical professionals were all scattered around the city in pandemonium. At the Cook County morgue, the scene can be described as a “cavalcade of police vehicles and ambulances delivering one corpse after another.” Reporters were criticizing the city’s delay in calling for an emergency. Citizens had wondered why the plan for cooling centers and public advisors wasn’t enacted earlier. Morgue volunteers were trying to get over the psychological effects of seeing massive piles of dead bodies all day. The police were frustrated with getting loved ones to check in on their own family members and report any problems. It seemed like every department had a different yet equally difficult task to handle. By the end of the day, the death toll had reached 269.4

Sunday July 16. The situation remained dire as calls continued to pour in as more bodies were discovered. The task of counting the number of casualties was difficult as more bodies were being discovered and accounted for by the hours. This cycle of counting and autopsies would continue on through October of that year. Those findings would ultimately conclude that 739 people died during the July heat wave. While this was happening, Mayor Daley had gathered his staff at City Hall to deal with the escalating crisis and intensifying media scrutiny. Reporters questioned why the city waited two full days to declare an emergency, why cooling centers weren’t employed sooner, and why the police weren’t asked to check on seniors sooner.5

Many lessons were learned and many questions were left unanswered. But, the biggest question that was still to be answered was what could they have done to prevent the deaths of over 700 people? Sociologist Eric Kilnenberg, who lived to witness the heat wave, years later offered a different way to combat such a disaster. As today we are all practicing “social distancing,” Kilnenberg believed that the practice of physical distancing rather than social distancing was the correct way to go. An example today could be to standing six feet apart from someone (physical distance) but still be able to be in their presence and maintain social interaction. Most of the victims were elderly people who did not have air conditioning and/or did not have any access to help. As a result, they died alone simply because they were socially distant from everything and everyone. Everyone still had their neighbors but everyone was so socially disconnected that the physical space did not matter or offer any help. It is like when a hurricane occurs, volunteers and organizations are out helping others and assisting in any way possible, but in 1995, Chicagoans had the “every person for themselves” mentality. They “socially distanced” from everyone else because they were only concerned for themselves. Even when people decided to socially reach out to others, they were already dead. Klinenberg offered the idea of having just a physical distance while maintaining a social connection with those who are vulnerable so that you could keep tabs on them. It is the willingness to check on someone’s health and well being while being physically distanced by a house down the street or even a room in your house, which can sometimes be the difference between life and death.6

To bring it to today’s pandemic reality, it can be the same as following the social mandates such as wearing a mask when out in public and staying six feet apart even if you aren’t sick. That act alone protects those who are vulnerable and gives them a chance to stay healthy. Another one is not hoarding up on necessities when there are those less fortunate who will need them more than you. For Klinenberg, the concept is simple: physically distant yourself, maintain social connection with others, and be courteous to those who are vulnerable because these acts can be the difference between saving lives or adding to a seemingly never-ending dilemma.

- Mike Thomas, “Chicago’s Deadly 1995 Heat Wave: An Oral History,” Chicago Magazine, July 2015. ↵

- Bonnie Miller Rubin and Jeremy Gorner, “Fatal Heat wave 20 years ago changed Chicago’s emergency response,” Chicago Tribune (Chicago, IL), July 15, 2015. ↵

- Mike Thomas, “Chicago’s Deadly 1995 Heat Wave: An Oral History,” Chicago Magazine, July 2015. ↵

- Mike Thomas, “Chicago’s Deadly 1995 Heat Wave: An Oral History,” Chicago Magazine, July 2015. ↵

- Mike Thomas, “Chicago’s Deadly 1995 Heat Wave: An Oral History,” Chicago Magazine, July 2015. ↵

- Eric Kilnenberg, “Denaturalizing Disaster: A Social Autopsy of the 1995 Chicago Heat Wave,” Theory and Society 28, no. 2 (1999): 239-95. ↵

23 comments

Rhys Kennedy

The relevance of this heatwave to today’s pandemic is rather striking due to both the issues and temporary solutions. In both cases, but just as interesting in the heatwave, there was an abnormally delayed response to the issue on top of lacking temporary solutions.

Lindsey Ogle

This is a really interesting article. I had never heard of the Chicago heat wave and it is crazy to think that people who are still around today might have gone through this once already. This a very well written article that has a lot to do with life today!

Leesa

What a wonderful article. Thank you for bringing this event which many have forgotten some awareness. And it’s so relevant to what’s going on right now in our country.