Research Question

Societal attitudes on strict/traditional gender roles facilitate and maintain acceptance of intimate partner violence (IPV). Victims of IPV who find it culturally normative from gender roles are more likely to experience guilt and shame and are then more likely to maintain the relationship. Likewise, perpetrators with accepting attitudes of strict gender roles are more likely to maintain them through IPV. Therefore, what is the relationship between patriarchal gender role attitudes and intimate partner violence?

Literature Review

Every twenty minutes, our nation experiences intimate partner violence, with one in four women being victimized (National Coalition Against Domestic Violence, n.d.). Intimate partner violence has become a global health concern characterized by “any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or mental harm to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or private life.” (United Nations, 1993). Communication and safety are integral parts of an intimate relationship and are essential for the health and well-being of everyone involved. However, research has found several characteristics that increase the risk of the perpetration of violence within a relationship.

Several studies have pointed to educational differences in perpetrators and their beliefs on gender roles (Santana et al., 2006; Wang, 2016). Despite finding these general links, it is imperative that more work be done to further the understanding of the complex variables involved in mediating intimate partner violence. Studies have found a general link between acceptance of aggressive attitudes and acting on that aggression with a partner (Archer & Graham‐Kevan, 2003; Husnu & Mertan, 2015). This means that a perpetrator may internally normalize aggressive behaviors and be desensitized when acting with violence. This lack of remorse and increased acceptance in responding to violence further exacerbates the cycle of abuse.

Possible explanations for this may be related to education. For example, in Santana et al. (2006), participants who acquired a GED compared to higher education reported elevated alignment with strict patriarchal ideologies. Specific to this study, participants highly agreed with 1. male control and dominance over their relationships, 2. male aggression and emotional detachment, 3. views that violence against women is a result of their defiance, and 4. adversarial attitudes against women. This study significantly contributes to previous research. In another study, it was found that participants with higher education did not believe that wife-beating was justified (Wang, 2016). Schooling often educates students on topics related to domestic violence, such as anti-bullying campaigns. Acquiring higher education also tends to include respectful and extensive dialogue among peers, facilitating accountability toward right and wrong actions. Therefore, education can intercept the development of a culture of violence. In discussing culture, a direct and often studied characteristic of intimate partner violence is attitudes toward gender roles. Both studies discussed above linked strong patriarchal beliefs and the risk of accepting attitudes of violence toward an intimate partner.

Research aiming to break down variables that can further demonstrate the complexity of domestic violence is necessary for gaining awareness. Patriarchal attitudes include topics related to male domination and women’s passivity as the ideal way of life. Previous research has added to this idea in discussing that the use of violence facilitates the subordination of women (Berkel, Vandiver, & Bahner, 2004). Across all studies mentioned, the majority of perpetrators are men. Violence against women raises violations of basic human rights and contributes to mental, physical, and reproductive issues (Kaur & Garg, 2008). It is common for women to be assigned to traditional gender roles of motherhood and passivity. Therefore, victims of intimate partner violence who find it culturally normative from gender roles are more likely to experience guilt and shame and are then more likely to maintain an abusive relationship.

This study aims to assess the relationship between societal attitudes on gender roles and intimate partner violence. With the numerous mental health issues among the negative impact abuse yields, awareness and action are necessary. If individuals align themselves with patriarchal attitudes, then they may facilitate and maintain acceptance of intimate partner violence. It is imperative to deconstruct the variables contributing to intimate partner violence in hopes of resolving the global crisis of domestic violence.

Hypotheses

H0: There is no relationship between gender roles and intimate partner violence.

H1: There is a significant relationship between gender roles and intimate partner violence.

Methods

Data

The experimental data come from the Crime, Health, and Intimate Partner Problems Survey (CHIPPS), a cross-sectional probability sample of St. Mary’s University undergraduate students (n = 200) designed to analyze differences in partner violence and religion. Students were randomly chosen via their student email. The survey was then disseminated via email so that participants could complete it on their computer or mobile device. Respondents were offered a $10 gift card to participate in the survey. Data was collected between Spring and Fall of 2024.

Measures

- Patriarchal Gender Role Attitudes. The question gauged opinions on men’s and women’s roles in society, with rating level of agreement on a woman’s place in the home. Initial responses were coded as “Strongly Disagree” = 1, “Disagree” = 2, “Agree” = 3, “Strongly Agree” = 4, and “No Opinion” = 5. Responses were recoded into “Strongly Disagree” = 0, “Disagree” = 1, “Agree” = 2, “Strongly Agree” = 3.

- Intimate Partner Violence. The dependent variable gauged the respondent’s level of agreement with the following statement: it is sometimes ok for an individual to beat their partner. Initial responses consisted of “Strongly Disagree” = 1, “Disagree” = 2, “Agree” = 3, “Strongly Agree” = 4, and “No Opinion” = 5. Responses were recoded to “Strongly Disagree/Disagree” = 0 and “Strongly Agree/Agree” = 1.

- Feelings about Current Relationship. Respondents were asked to gauge their “level of happiness toward their current relationship.” Responses consisted of “Very unhappy” = 0, “Unhappy” = 1, “Happy” = 2, and “Very happy” = 3.

- Respondent’s Age. Age (in years) was recorded by asking respondents, “How old are you?”. Respondents answered anywhere from 18 to 22 years of age.

- Gender. Gender was coded by asking respondents to indicate their gender. Initial responses included “Male” = 1, “Female” = 2, “Transgender” = 3, and “Other” = 4. Due to few responses in the “Transgender” and “Other” categories, this variable was dichotomized so that “Male” = 0 and “Female” = 1.

- Race/Ethnicity. To ascertain the respondent’s race/ethnicity, they were asked, “With which group do you most closely identify?” Response categories ranged from “Non-Hispanic White” = 1, “Hispanic” = 2, “African American” = 3, “Asian” = 4, and “Other” = 5. The variable was then recoded into a series of four dummy variables with “Non-Hispanic White” as the reference group (e.g., Hispanic/African American/Asian/Other = 1, Else = 0).

- Household Income. To gauge the total income in respondents’ households, they were asked to “select the category that gives the best estimate of your total annual household income (income of all family living in your home) before taxes in the last year (not including scholarships or grants).” Possible responses ranged from “None/Under $5,000” = 0 to “$75,000 or more” = 10.

- Class. Respondents were asked to identify their current student classification. This classification follows the Office of the Registrar’s method, which bases classification on the total amount of hours (including those currently enrolled by the student) when determining their classification. These options included “Freshman” = 0, “Sophomore” = 1, “Junior” = 2, “Senior” = 3.

- Employment Status. Lastly, respondents were asked to identify their current employment status. Responses included “Other” = 0, “Unemployed” = 1, “Part-time” = 2, “Full-time” = 3.

Results

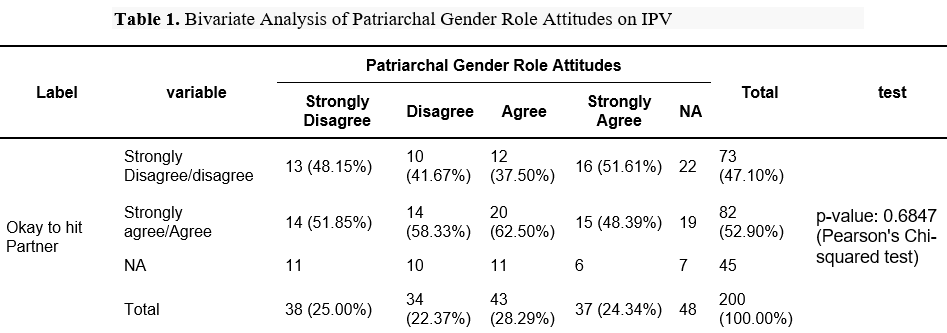

To examine the relationship between patriarchal gender role attitudes that women should stay at home (Strongly disagree, Disagree, Agree, Strongly agree) and intimate partner violence (OK to hit partner – Strongly disagree/Disagree, Strongly agree/Agree), a Chi-Square test for Independence was conducted as demonstrated in Table 1. Results indicate a lack of association between levels of agreement that a woman’s place is at home and levels of agreement or acceptance toward hitting an intimate partner (x^2(3) = 1.49, p = 0.68). This indicates that opinions on intimate partner violence are independent of an individual’s traditional belief that women should stay home. Therefore, the null hypothesis is accepted because the results support the statement that there is no significant association between the variables tested.

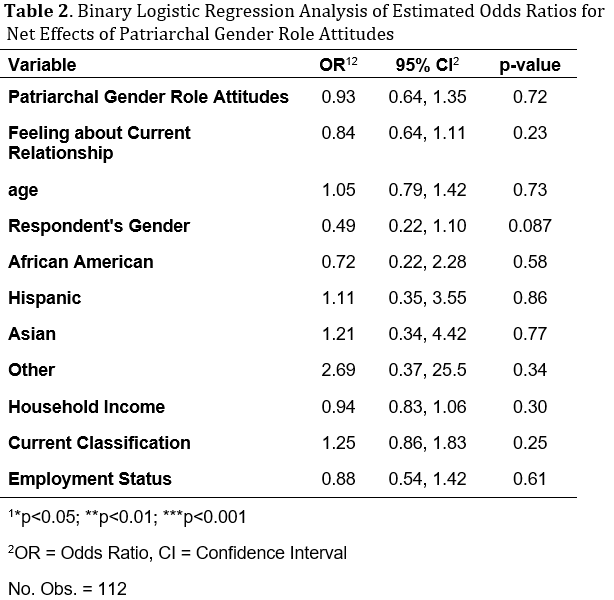

The aim of this statistical test was to assess the influence of patriarchal gender role attitudes (coded as Strongly disagree/Disagree = 0 and Strongly agree/Agree = 1) on intimate partner violence. Results, as shown in Table 2, indicate that patriarchal gender role attitudes were a negative but nonsignificant predictor of intimate partner violence. Furthermore, the analysis produced an odds ratio (OR) of 0.93, with a 95% confidence interval (CI) of 1, p = 0.72. Had the results been significant, patriarchal gender role attitudes could have been a significant predictor, with each unit decreasing the odds of intimate partner violence by 0.93 times (agreeing that it is ok to hit partner – 1 versus disagreeing – 0). Given that no significant increase or decrease was found, the null hypothesis can be accepted.

Conclusion

This study aimed to assess predictors of intimate partner violence, specifically focusing on patriarchal gender role attitudes. It is a traditional belief that women belong at home, but recent decades have shown many women turning away from tradition and entering male-dominated fields. Despite the continued feminist waves, women tilting the gender gap in the workforce, and egalitarian relationships – intimate partner violence remains prevalent. The variables of interest in this study included patriarchal gender role attitudes relating specifically to the belief that women belong at home and intimate partner violence indicative through the belief that it is ok to hit one’s partner. It was anticipated that belief in traditional gender roles would predict intimate partner violence. In other words, if it is accepted that women belong at home, then any deviation from the traditional obedient woman would enhance acceptance of intimate partner violence to maintain control. Both statistical tests in this study, the Chi-square test of independence and binary logistic regression, produced nonsignificant results. Therefore, there was no significant association between traditional gender role belief and intimate partner violence, as found in the Chi-square test. Then, for the binary logistic regression, even when controlling for all other variables, patriarchal gender role attitudes were a nonsignificant predictor. It is possible that using the variables at hand requires further deconstruction, given the complexity of ideas on intimate partner violence. Using patriarchal gender role attitudes as a single measure may be too inexplicable, as found in a previous study that assessed traditional ideologies against women (Watto, 2009). A potential solution to this issue may be creating subdimensions of traditional patriarchal ideas to tackle a greater range of predicting IPV. Further research should continue to explore and assess opinions toward women in perpetuating violence against them within an intimate relationship.

References

Archer, J., & Graham‐Kevan, N. (2003). Do beliefs about aggression predict physical aggression to partners?. Aggressive Behavior: Official Journal of the International Society for Research on Aggression, 29(1), 41-54.

Copp, J. E., Giordano, P. C., Longmore, M. A., & Manning, W. D. (2019). The Development of Attitudes Toward Intimate Partner Violence: An Examination of Key Correlates Among a Sample of Young Adults. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 34(7), 1357-1387.

Husnu, S., & Mertan, B. E. (2017). The roles of traditional gender myths and beliefs about beating on self-reported partner violence. Journal of interpersonal violence, 32(24), 3735-3752.

Kaur, R., & Garg, S. (2008). Addressing domestic violence against women: an unfinished agenda. Indian journal of community medicine : official publication of Indian Association of Preventive & Social Medicine, 33(2), 73–76. https://doi.org/10.4103/0970-0218.40871

Melander, G., Alfredsson, G., & Holmström, L. (2004). Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women: Proclaimed by the General Assembly of the United Nations on 20 December 1993. In The Raoul Wallenberg Institute Compilation of Human Rights Instruments (pp. 247-253).

Brill Nijhoff. Nabors, E. L., & Jasinski, J. L. (2009). Intimate partner violence perpetration among college students: The role of gender role and gendered violence attitudes. Feminist Criminology, 4(1), 57-82. National Coalition Against Domestic Violence (n.d.,) National Statistics. https://ncadv.org/STATISTICS

Santana, M. C., Raj, A., Decker, M. R., La Marche, A., & Silverman, J. G. (2006). Masculine gender roles associated with increased sexual risk and intimate partner violence perpetration among young adult men. Journal of urban health, 83, 575-585.

Wang, L. (2016). Factors influencing attitude toward intimate partner violence. Aggression and violent behavior, 29, 72-78.

Watto, S. A. (2009). Conventional patriarchal ideology of gender relations: an inexplicit predictor of male physical violence against women in families. European Journal of Scientific Research, 36(4), 561-569.

- 64, 1.35 ↵

1 comment

Lauren Sahadi

This was a very important subject matter. I like how it was a study format and the findings were really interesting. It shows that there needs to be future research and intervention strategies for intimate partner violence. I like that you added visuals to understand the research. This was a very great article/study and it brings much needed awareness to this issue.