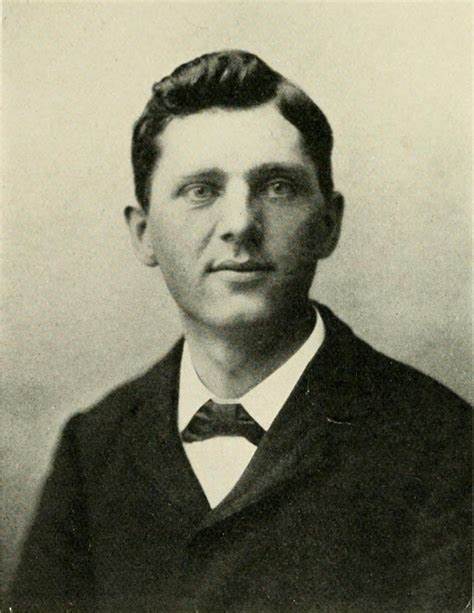

Rarely in American history has there been a figure as controversial and ambiguous as Leon Czolgosz (pronounced Chow-Gah-Sh). Particularly in the context of Presidential assassinations, it is presumed that much would be known about the assassin himself, typically after the assassination has taken place. But in the case of Leon Czolgosz, his life and motivations still remain somewhat of a mystery, with ardent speculation about both still taking place to this day.

The primary details that are known about his motivations come from Leon himself at his trial. It is reported that after his sentencing, Czolgosz claimed that no one else was involved with McKinley’s assassination, no one paid him to kill McKinley, no one ordered him to kill McKinley, and that he thought killing McKinley would benefit working-class people. Yet, what we will explore goes beyond what Czolgosz himself claims, and an analysis of his early life, economic history, his introduction into the Anarchist Movement, and his mental health will seek to expose, at least in part, one of America’s most infamous presidential assassins.1

Leon F. Czolgosz is thought to have been born in either Detroit or Alpena, Michigan sometime during 1873. As no official birth certificate exists for him, it is unlikely that the official date will ever be discovered. The “F” initial in Leon’s name is fake, as it does not stand for anything, and it is thought that he just liked having the extra initial in his name. His parents themselves were from Poznan, Prussia and immigrated to America sometime between 1871 and 1873.2 From his own account, Leon said that he attended small common schools when he was younger, as well as attending local Catholic schools, as he had been raised within the Catholic faith.3 Paul Czolgosz, Leon’s father, described him as being quiet and reserved as a child, refusing to play with other children.4

Other insights about Leon’s personal life come from his brother and sister, Victoria and Jacob. One particular account they gave about him was his relationship with their stepmother when he was older. Leon’s mother died sometime between 1893 and 1895, and his relationship with his stepmother began to worsen as he often avoided her whenever they were both at home. They were said to have constantly gotten into arguments and could never agree on much of anything. But beyond a rather fractious relationship, nothing else seems to have materialized from their relationship.5

As Leon grew older, accounts of his employment and labor history were far more varied among the various sources that offer them. The more accepted account is that Leon worked on his family’s farm, in various lumber mills, did time as a wire thresher in a bottle works factory, and in a glass factory. His years of employment between his professions as a day laborer are generally thought to have begun when he was six years old and ended sometime in 1898, when he left his job in the glass factory. It is after these years of employment that we begin to see a more politically active Leon, as he began to gain an interest in the anarchist movements taking place within America at the time.6

The exact time Leon started to develop his anarchist political views is unknown; however, what is known is that he, like other contemporary anarchists, most likely progressed to anarchism from socialism. His conversion displayed his willingness to learn about anarchist theory and practices, yet he is not known to have been directly involved with any particular anarchist groups or maintained any close connections with any of its leaders. Perhaps the most influential force on Leon’s anarchist beliefs was Emma Goldman, one of the most famous American anarchist leaders and apologists.7 It was noted within several newspapers that on May 5, 1901, four months before the assassination, Leon had attended a speech given by Goldman who was praising recent violent actions enacted by fellow anarchists. While her speech isn’t directly linked with Leon’s decision to assassinate McKinley, it did entangle her political beliefs with Leon’s actions.8 Leon was so impressed by the speech that he sought out Goldman, who was in Chicago at the time, and he managed to speak briefly with her on May 12, 1901 as she was departing. Goldman had introduced Leon to another anarchist friend by the name of Abe Issak, Sr., who was an editor for the anarchist newspaper Free Society. This interaction between the three would be their only one, and neither Goldman nor Issak saw Leon in person again.9

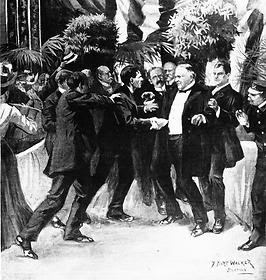

Not much is known about Leon’s whereabouts between his departure from Chicago and his arrival in Buffalo, New York, where the assassination would occur. The only well-known documentation comes from reports about his immediate presence at the Pan-American Exposition several days before the assassination and following it. The Exposition was intended to be a host for and by western nations to display the modern inventions of the day. At the Pan-American Exposition of 1901, the main attraction was electricity. McKinley’s secretary, George B. Cortelyou, had advised McKinley that his greeting session within the exposition’s Temple of Music could be dangerous, as he wouldn’t be as protected surrounded by lines of people. Courtelyou even attempted to remove the event from McKinley’s schedule altogether, but McKinley dismissed his concerns. He then compensated by requesting more security from the Buffalo authorities.10

At the same time, Leon’s plan had begun. He first tried getting close to McKinley at Buffalo’s railroad station when McKinley had arrived for the Expo on September 4, 1901. He was spotted by a police officer who noticed him pushing his way through the crowd and was pushed back himself. Leon tried again the next day on September 5, when McKinley was on a podium giving a speech, but hesitated and lost his chance at shooting him there and then when McKinley was escorted away after he was finished speaking. However, on September 6, 1901, Leon’s plans came to fruition and skyrocketed him to national infamy.11

As mentioned previously, George B. Cortelyou had requested more security from Buffalo authorities to guard McKinley during the exposition. The security detail included police officers, exposition guards, soldiers, and even Pinkerton detectives. Yet, they were situated in such a way that McKinley and the exposition’s President Millburn were blocking their line of sight from the people coming forward to shake their hands.12 To make matters worse, both direction and coordination were lacking among the detail members, as agent training and protective procedures had not yet been developed for presidential security.13

It was in this vulnerable moment that Leon struck. Using a handkerchief, he had managed to conceal a .32 caliber Iver-Johnson revolver and wrapped the handkerchief around his hand to give it the appearance of a bandage. As Leon was not checked before he entered into the Temple of Music, the guards never found the revolver, and all he had to do was wait until he got close enough to McKinley. As Leon approached the president and was about to shake his hand, two gunshots rang out in the building. The first gunshot struck McKinley in his sternum, but did not penetrate deeply because of a button on his coat. The second gunshot struck McKinley in his stomach as it entered through his left abdomen, fatally wounding him. Leon was then immediately tackled and taken into custody following the shooting.14

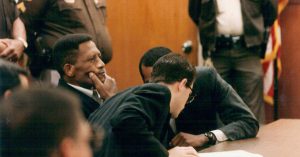

McKinley wouldn’t die until eight days later after, the bullet wound became infected with gangrene in both his stomach and pancreas. Had the doctors been able to find and locate the bullet itself, he might have lived.15 The political fallout from the assassination saw the arrests of hundreds of American anarchists, Issak Sr. and Goldman among them, yet virtually all of them were freed due to a lack of evidence connecting them to Leon and McKinley’s assassination.16 Leon’s trial itself was rather expeditious in its nature, as it began on September 23, and by September 24, Leon had already been tried and convicted of 1st degree murder by a jury.17 As mentioned previously, Leon had no intention of claiming insanity, and had even insisted that he had acted consciously. And with all the evidence stacked against him, it wouldn’t have taken a jury very long to find him guilty. And so, on October 29, 1901, seven weeks after he had shot McKinley, Leon Czolgosz was executed by means of electric chair, and his remains were destroyed using acid.18

The ascension of Teddy Roosevelt marked a new era for the United States, in particular the questions surrounding presidential security in the future. The years following the assassination marked the establishment of the Secret Service as the official protection detail for the President in 1907, and being first utilized in 1908-1909. It also marked the end to the widespread idealization of the presidency as a position in American society exempt from harm, and it wouldn’t be until president Taft that the Secret Service itself would become a mainstay within the American Presidency.19

- Mel Ayton, “The Anarchists and William McKinley,” in Plotting to Kill the President, Assassination Attempts from Washington to Hoover (University of Nebraska Press, 2017), 170-171. ↵

- Cary Federman, “The Life of an Unknown Assassin: Leon Czolgosz and the Death of William McKinley,” Crime, Histoire & Sociétés / Crime, History & Societies 14, no. 2 (2010): 86. ↵

- LeRoy Parker, “The Trial of the Anarchist Murderer Czolgosz,” The Yale Law Journal 11, no. 2 (1901): 93. ↵

- Cary Federman, “The Life of an Unknown Assassin: Leon Czolgosz and the Death of William McKinley,” Crime, Histoire & Sociétés / Crime, History & Societies 14, no. 2 (2010): 86. ↵

- Cary Federman, “The Life of an Unknown Assassin: Leon Czolgosz and the Death of William McKinley,” Crime, Histoire & Sociétés / Crime, History & Societies 14, no. 2 (2010): 91-92. ↵

- Cary Federman, “The Life of an Unknown Assassin: Leon Czolgosz and the Death of William McKinley,” Crime, Histoire & Sociétés / Crime, History & Societies 14, no. 2 (2010): 89. ↵

- Dan Colson, “Propaganda and the Deed: Anarchism, Violence and the Representational Impulse,” American Studies 55/56 (2017): 176. ↵

- Dan Colson, “Propaganda and the Deed: Anarchism, Violence and the Representational Impulse,” American Studies 55/56 (2017): 177. ↵

- Sidney Fine, “Anarchism and the Assassination of McKinley,” The American Historical Review 60, no. 4 (1955): 781. ↵

- Mel Ayton, “The Anarchists and William McKinley,” in Plotting to Kill the President, Assassination Attempts from Washington to Hoover (University of Nebraska Press, 2017), 166. ↵

- Mel Ayton, “The Anarchists and William McKinley,” in Plotting to Kill the President, Assassination Attempts from Washington to Hoover (University of Nebraska Press, 2017), 166, 167. ↵

- Mel Ayton, “The Anarchists and William McKinley,” in Plotting to Kill the President, Assassination Attempts from Washington to Hoover (University of Nebraska Press, 2017), 167. ↵

- Richard B. Sherman, “Presidential Protection during the Progressive Era: The Aftermath of the McKinley Assassination,” The Historian 46, no. 1 (1983): 1. ↵

- Mel Ayton, “The Anarchists and William McKinley,” in Plotting to Kill the President, Assassination Attempts from Washington to Hoover (University of Nebraska Press, 2017), 168. ↵

- Mel Ayton, “The Anarchists and William McKinley,” in Plotting to Kill the President, Assassination Attempts from Washington to Hoover (University of Nebraska Press, 2017), 169. ↵

- Sidney Fine, “Anarchism and the Assassination of McKinley,” The American Historical Review 60, no. 4 (1955): 781-782, https://doi.org/10.2307/1844919. ↵

- LeRoy Parker, “The Trial of the Anarchist Murderer Czolgosz,” The Yale Law Journal, (1901): 80. ↵

- Mel Ayton, “The Anarchists and William McKinley,” in Plotting to Kill the President, Assassination Attempts from Washington to Hoover (University of Nebraska Press, 2017), 168. ↵

- Richard B. Sherman, “Presidential Protection during the Progressive Era: The Aftermath of the McKinley Assassination,” The Historian 46, no. 1 (1983): 17-18. ↵

4 comments

Andrew Ponce

Hello Nathaniel! This article is not only informative, but fun to read for the audience. Very few people know about Leo Czolgosz; however, this article makes his story seem intriguing and historically impactful. This particular character’s story is one that engages the reader already, but it is the articulation of the writer that makes this story one to remember. Great publication

Gaitan Martinez

Leon Czolgosz just seems everywhere, his story reminds me of Charles Guiteau, the man who assassinated President James garfield. The whole reason behind the assassination was because Guiteau was fed up with life, and wanted to be remembered. To add on, he specifically chose the pistol he used because he thought it would look cool in a display case.

Christian Lopez

When thinking about the assassination of presidents man people think about John Wilks Booth and Lee Harvey Oswald but most people including myself(A history buff) almost never hear of Leon Czolgosz. Its interesting from a history stand point to see the other side of these tragic events.

Nathaniel Liveris

I know right! The event certainly doesn’t get enough recognition for the amount of political change it evoked within America, especially since it allowed Teddy Roosevelt to ascend to the Presidency.