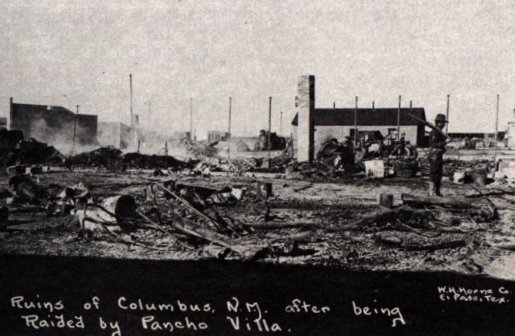

As the European powers tore themselves apart in the Great War’s bloodiest year, 1916, American blood was being spilled, not on the high seas but on American soil. The settlement where this took place was the border town of Columbus, New Mexico, only three miles away from the US-Mexican Border. Columbus was one of those towns that seemed abandoned as soon as it was founded. The small village was an uneventful place, where not even a single tree grew for miles in any direction, nor grass. It had dirt roads and sun-bleached buildings covered in dust. The only connection to the rest of the United States was a small depot with a single-line railroad where a train came through three times a day with passengers, goods, and letters. However, in 1916, Columbus was experiencing an economic boom, thanks to the settlement’s rich natural resources of silver, lead, and zinc deposits in the surrounding fields. Set on the outskirts of the town, home to 350 individuals, was Camp Furlong, headquarters of the 13th Cavalry Regiment.1

Soldiers of Camp Furlong had experienced fighting with Native Americans and with insurgents in the Philippines. Their duty was to patrol sixty-eight miles of border with only 553 men. Most of their patrolling range was through rough mountains ideal for rustlers, smugglers, and miscreants wishing to avoid border officials at the checkpoints. Already a difficult task for an understaffed unit, however, 12.4 percent of the soldiers in the military district were guilty of alcohol-related offenses and drug abuse. Later, a modern-day study from Fort Bliss stated that “It’s clear that at least some of the 13th [Cavalry in Columbus] would have been under the influence of alcohol and drugs at any given point.”2

The sickbay became crowded with men suffering from sunstroke, infections from cactus needles and other sharp-edged plants, food poisoning, and venereal diseases.3 Despite the news that Mexican Revolutionaries were on a rampage in Northern Mexico, raiding trains and stripping and executing American businessmen, rumors were spreading that they were moving across the border on the warpath, and Columbus was a possible target. The people of Columbus and the soldiers of the 13th went about their business. However, unknown to them, spies were already in the town, reconning the layout of Camp Furlong, the locations of stores, and the homes of officers and officials.4

When the attack came, it seemed like any other peaceful, warm early morning on that March 9th, until the crackle of gunshots broke out, breaking the silence. At first, some of the town folk awakened, thinking it was a skirmish between the many factions of the Mexican Revolution, as the border was only three miles away. The town folk occasionally watched the fray as a form of entertainment. But these shots were close, much closer. One of the shots struck the clock hanging from the town train depot, permanently freezing the clock at the time when the attack on the town started, 4:15 am—signaling for the attack to begin, much like we’ve seen in western films portraying a horde of outlaws and bandits attacking a defenseless town. However, these men were not outlaws; they were experienced soldiers belonging to the División del Norte, or the Division of the North, who were part of the Conventionalist faction in the violent Mexican Revolution. Not since the War of 1812 had a foreign army invaded the Continental United States.

The invading force was composed of nearly 500 mounted men and separated into five groups, hitting the town, the small train station, and Camp Furlong. It took thirty minutes for the U.S. Cavalry troops to break out of the camp, thanks to the quick thinking and leadership of a few of the junior officers and NCOs of the cavalry company, who moved towards the town, turning the quiet streets into a warzone. Bullets were flying in every direction, people and horses were getting shot and killed, buildings were being looted and burned down, and the fires resembled the sunrise hours earlier. The battle continued for almost another three hours when the Mexican soldiers fell back when the bugle called at 7:30 pm, and men from F Company pursued the retreating attackers. The battle continued from the town to the border and fifteen miles into the state of Chihuahua in Mexico. However, after fighting and hard riding for eighteen miles, the American horses were hot and tried, and their riders were low on ammunition. The Americans had to disengage the pursuit and return to Columbus, which was still smoking and burning.

The men from the División del Norte escaped with over 300 rifles and shotguns, 80 horses, and 30 mules, along with food and medical supplies. The Battle of Columbus, New Mexico also resulted in the deaths of 10 civilians, 8 American troops, and 15 injured. In comparison, the División del Norte suffered 67 deaths in the town and nearly 100 more while falling back to Mexico. Several more were either captured or injured.5

However, all of the captured equipment, animals, and supplies were all secondary objectives for the man who led the attack on Columbus, New Mexico; the reason for the attack was one of revenge and punishment on the United States. President Woodrow Wilson decided to end American support of this man, and instead Wilson gave his support to Venustiano Carranza and his Constitutionalist faction and de facto authority of Mexico, to end the conflict on the United States’ southern border.

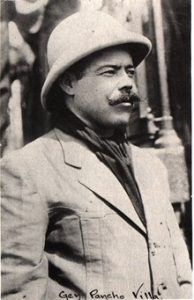

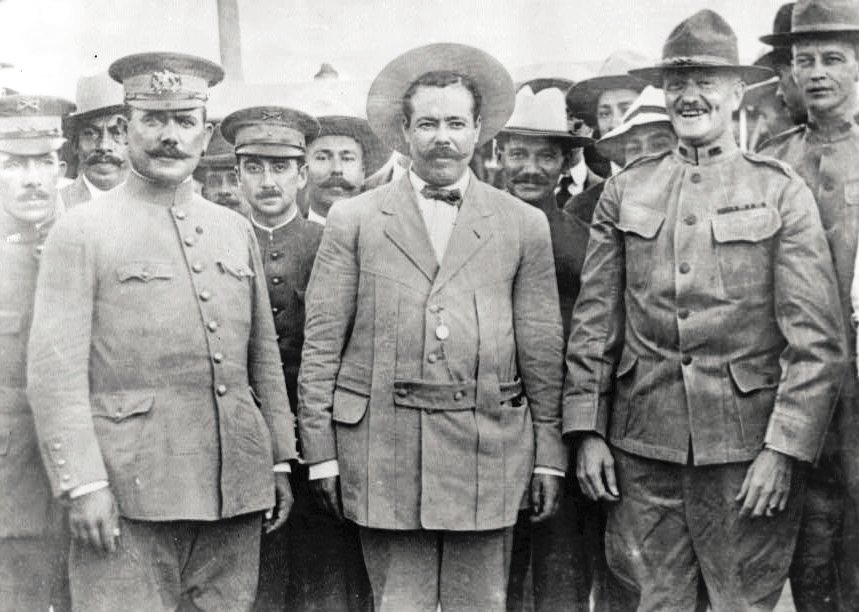

The man leading the raid on Columbus was controversial. To some, he was a criminal and a murderer; to others, he was a popular hero of the people, a Robin Hood character who stole from the rich and gave to the poor. He had even met General John Pershing and a newly commissioned 2nd Lieutenant George Patton, who had been his friends at Fort Bliss, El Paso, in 1913. He was none other than Francisco “Pancho” Villa.6

The Northern Lion: Francisco Pancho Villa

José Doroteo Arango Arámbula, or as most will know him as Francisco “Pancho” Villa, was well known long before the Battle of Columbus, New Mexico. His early life is a mystery, but most sources would agree that Pancho Villa was born on June 5, 1878, in San Juan del Río, Durango, Mexico, and was the eldest child in his family. Pancho Villa claimed that he never went to school. However, he did learn how to read and write from the town’s church. Nevertheless, for most of his young life, he worked to support his mother after his father’s death; he worked variously as a sharecropper, a muleskinner, a butcher, and a bricklayer. Alternatively, the young Pancho Villa was often found playing cards with his friends, or also fighting them. At sixteen, he moved to Chihuahua to work as a freight driver between Guenacevi and Chihuahua.7

The event that started Pancho Villa’s hatred of the Mexican aristocrats and wealthy class was when he received a letter from his mother telling him that his sister, Martina, had been raped by a man named Leonardo Negrete, the ranch owner’s son, near his home town. Soon Pancho Villa left his work and rode hard through the night back to San Juan del Río to exact revenge for his sister. Pancho Villa rode into town the following day. When Pancho Villa found Leonardo Negrete and confronted him, Negrete denied raping Pancho Villa’s sister; naturally, this led to heated arguments, and it resulted in Pancho Villa killing Negrete.8 In that single moment, Pancho Villa set off on his path of banditry, and he became a legend; he fled to the Sierra Mountains and joined the bandit gang that roamed the region. The band of outlaws of fifty men had been led by Ignacio Parra, another famous bandit and local legend. He took Pancho Villa under his wing and taught him the skills of being an outlaw, while also winning the band’s friendship.9

When the law caught up with Parra and killed him, the band of outlaws looked to Pancho Villa as their next leader. It was a role that suited Pancho Villa well, for the heart and mind of Pancho Villa was that of a man of action and boldness. He was an enemy of the status quo and of order; he was becoming a man of violence. Pancho Villa changed the band of outlaws from one that rustled just horses and cattle to one that raided ranches and towns, mining companies and trains, leaving a path of destruction, death, and discord in its wake. The bandits gave a portion of the plunder to the poor, quickly becoming popular among the peasant class of Mexican society.10

In 1902, the rural police force, called the Rurales, arrested Pancho Villa and charged him with assault and rustling livestock, marking him for death. With his connection with Pablo Valenzuela, a local cacique to whom Pancho Villa had sold much of his stolen cattle over the years, Pancho Villa’s punishment was reduced from a sentence of death to one of service in the Mexican Federal Army, one of the most hated institutions of the Mexican Republic, often used to violently crush protests and rebellions that were breaking out with ever more frequency. After several months, he deserted the army and returned to his band of outlaws.

From that point to 1910, Pancho Villa would alternate between living as an outlaw and as a law-abiding citizen. But then, in 1910, the Mexican Revolution flared up against the government of Porfirio Díaz, igniting twelve different factions ranging from counter-revolutionaries to communists, becoming one of the few true revolutions in history that started with the lower classes taking control of the country.11

During the Mexican Revolution, Pancho Villa distinguished himself as a competent leader, becoming well-liked by his troops, often seen eating with them. He took advice from his officers during much of the decision-making process. During the war, Pancho Villa was famous for using the fighting styles of Apaches and Comanches, charging at full speed at the enemy while firing their carbines and rifles. As a reward for his actions, Pancho Villa was granted governorship over the State of Chihuahua in December 1913. Pancho Villa quickly stabilized the state with a new regional currency. Even a few businesses and banks recognized the currency in Texas, where allegedly, Pancho Villa hid a large amount of money. Along with a stable currency, he used military force against further uprisings and counter-revolutionaries. He also created schools and programs to protect widows. He even redistributed land from the wealthy to the poor.12

However, Pancho Villa did not see only glory and victory; he tasted defeat more than a few times, and not just from the Mexican Federal Army but also from other factions, such as that of the Constitutionalists and their leader Venustiano Carranza, Pancho Villa’s former friend, who had given him his political position. Once Carranza was in control of the country, the revolution turned into a civil war due to the different agendas of the factions. The Constitutionalist faction during this time cut funds for the División del Norte, to control them more effectively and greatly reduce the strength of Pancho Villa.

Reducing Pancho Villa’s strength became a problem of legal and questionable means. Carranza sold the filming rights of battles to the Mutual Film Corporation, which limited battles to daytime attacks for filming purposes.13

One of Pancho Villa’s more famous means of gaining funds with less than legal means was when he and his men attacked the Mexican Northwestern Train No. 7 in Southern Chihuahua on April 9, 1913. Pancho Villa and 25 men boarded the train and captured the cargo of 122 bars of silver bullion, which, at the time, was worth $160,000 US dollars, which would now be worth over $4.5 million dollars in today’s money.14 He held the silver for ransom against the mining company that the precious metal belonged to—using Wells Fargo as the intermediary for an exchange of $50,000 cash paid in pesos by the mining company.15 Pancho Villa’s thirst for violence and discord was not quenched with his diminished resources and his responsibility as governor; however, the revolutionary leader remained popular among the people on both sides of the border.

The American Respond

The attack on Columbus was the latest skirmish and bloodshed on the Mexican-American border. There had earlier been the Bandit War on a section of the Texas border. The U.S. government could no longer delay taking action against Mexico. The public and military officers demanded war and justice for the Americans who had been injured or killed. However, the U.S. Congress under the Wilson administration did not declare war on Mexico but rather on Pancho Villa and his division.

Part of Wilson’s speech towards Congress and the Mexican de facto government shows that the American intervention was only to capture Pancho Villa and should not be viewed as an invasion.

“This can and will be done in entirely friendly aid if the constituted authorities in Mexico and with scrupulous respect for the sovereignty of that Republic.”16

On March 10, Congress authorized an expedition to capture or kill Pancho Villa. The War Department followed up with Coded Message 883 to General Frederick Funston, commander of the Southern Department:

“You will promptly organize an adequate military force of troops under the command of Brigadier General Pershing and will direct him to proceed promptly across the border in pursuit of the Mexican band which attacked the town of Columbus and the troops there on the morning of the ninth instant. These troops will be withdrawn to American territory as soon as the de facto government in Mexico is able to relieve them of this work. In any event the work of these troops will be regarded as finished as soon as Villa band or bands are known to be broken up. [In carrying out these instructions you are authorized to employ whatever guides and interpreters necessary and] you are given general authority to employ such transportation including motor transportations, with necessary civilian personnel as may be required. The President desires his following instructions to be carefully adhered to and to be kept strictly confidential. You will instruct the commander of your troops in the border opposite the states of Chihuahua and Sonora, or, roughly, within the field of possible operation of Villa and not under the control of the forces of the de facto government, that they are authorized to use the same tactics of defense and pursuit in the event of similar raids across the border and into the U.S. by a band such as attacked Columbus yesterday. You are instructed to make all possible use of auroplanes at San Antonio for observation. Telegraph for whatever reinforcement or material you need. Notify this office as to force selected and expedite movement.”17

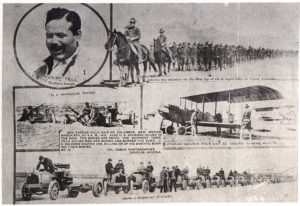

By March 14, 4,800 Regular troops had assembled at Columbus and Culberson’s Ranch, a hundred miles west of the border town. The Expeditionary Force was expanded to 10,000 regulars, supported by an additional 110,000 members of National Guards from Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico. The upcoming operation was in Chihuahua, a region of mountains and deserts, and with the restriction that Washington D.C. placed on the expedition. President Wilson and the Secretary of War Newton D. Baker assigned Brigadier General John J. Pershing as the commander of the Mexican Expedition.

John “Blackjack” Pershing

John Joseph Pershing was born on September 13, 1860, in the small city of Laclede, Missouri, and was one of five children to a farmer-and-shopkeeper father and housemaker mother. Pershing studied scientific didactics at Truman State University with his sister, Elizabeth. One day as the siblings were studying together, Pershing noticed an announcement in the weekly newspaper that there would be an upcoming examination in Trenton, Missouri, held by the Honorable Joseph H. Burrows, to interview boys interested in attending the Military Academy at West Point. With some encouragement from his sister and with permission from his professors for a period of absence from class, Pershing left for his future, winning the congressional nomination. Pershing became part of the class of ’86 at West Point.18

When he arrived at West Point, along with a hundred and forty-four other candidates, despite the hazing, Pershing was excited to attend the same academy that some of the greatest American officers had studied at, such as Grant, Lee, Sherman, Jackson, and other such men before him. Every moment would be dedicated to studying, drills, meals, recreation, and sleep for the next four years of his life. Pershing struggled academically, yet he was determined to succeed. Pershing managed to graduate 30th out of a class of 77; the rest had dropped out during the four years. At the time, the three most popular branches of the U.S. Army were engineering, artillery, and cavalry. Pershing picked the Sixth Cavalry Regiment because, in his words, “mainly the reason that it was the action in the Southwest against the Apache Indians.”19 Another was that the regiment, organized in 1861, saws some of the bloodiest battles in the American Civil War. By July 1886, Pershing arrived at Fort Bayard, New Mexico, the headquarters of the Sixth Cavalry.

While in New Mexico, Pershing saw the end of the Apache campaign; however, the Sixth was then ordered to South Dakota to assist in the campaign against the Sioux nation, more specifically, the Lokatas, lasting from November 1890 to August 1891—operating just outside of the Bad Land in South Dakota. Pershing noted in his journal that, even as a junior officer, he believed that Colonel Forsyth’s handling of the situation at Wounded Knee Creek was poor, making his regiment’s operations more difficult for the tribes in the area who were on the verge of surrendering.20

While in the Dakotas, Pershing, for a brief time, commanded a troop of Sioux Indian Scouts, who enlisted for six months during his time there. While serving with them as policing unit, Pershing was impressed with the skills of his men and their eagerness to learn. After his time with the Sioux Scouts, Pershing spent time as a military instructor at the University of Nebraska. Then Pershing served in the 10th Cavalry, a Buffalo Soldier unit, as both 1st lieutenant and captain, where he gained the nickname “Blackjack,” a name he was never fond of, yet it stuck with him for the rest of his career, and beyond. Pershing served with the unit during the Spanish-American War, where the 10th, along with support from the 1st Volunteer Cavalry, better known as the Rough Riders, successfully captured San Juan Hill.

After the Spanish-American War, Pershing became a senior officer working in the War Department as a Customs and Insular officer. He visited the Philippines, Great Britain, France, Italy, and Egypt, then served as an Adjutant General briefly in the beginning phases of the American-Philippine War. From 1902 through 1903, Pershing saw combat in the Lake Lanao Expedition among the Moro people, referring to the thirteen Muslim-majority ethnolinguistic groups found in the southwestern provinces of Mindanao.21 The Moro people had a long history of resisting colonial rule dating back to the fifteenth century.

When the Insular Government of the Philippines wanted to assimilate the Moro People into the Philippines’ national identity and end the Moro practice of feudalism and slavery, these actions caused the Moro people to rebel by first attacking American troops near Lake Lanao. Fighting with firearms and swords, they were some of the fiercest fighters that the American forces faced during the war.22 Between June 1903 and January 1905, Pershing returned stateside and worked on the General Staff. He also married his first love Helen Frances Warren, daughter of Emory Warren, the senator of Wyoming and a powerful man in the Republican Party. However, the time Pershing spent back in the United States was brief. He once more had to travel across the Pacific Ocean and act as the military attaché in Tokyo, Japan, as an observer of the Imperial Japanese Army while they were in Manchuria, allowing the United States to witness the development of their modern warfare.23

Pershing returned to the Philippines in 1909, first to fight the remaining pockets of resistance there, and then to become the military governor of the Moro Province, while also being promoted to Brigadier General, passing several senior officers above him. He helped develop agriculture, markets, education, and public works there. As military governor, the American Federal Government sent him on two diplomatic missions. The first was to Hong Kong to celebrate, along with every corner of the British Empire, the coronation of King George V on June 22, 1911. In contrast, the second mission was a more somber event, which was the funeral of Emperor Meiji, along with many of the representatives from the leading European powers, such as Great Britain and Germany. The ceremony was set for midnight on September 13, 1912.24

At the end of his term as the military governor, he felt a mixture of relief and regret leaving the Philippines for the final time for his next duty as the commander of the Eighth Brigade, at the time stationed in San Francisco, California. Pershing discovered that his direct superior, Major General Arthur Murciso was one of his old instructors at West Point. Pershing also reunited with another old friend, Buffalo Bill Cody, who often sent complimentary tickets to his “Wild West” show to Pershing and other military friends. Pershing enjoyed these shows, for it reminded him when he served with the Sioux Scouts as a lieutenant.

However, not all were pleasant reunions and fond memories. For tragedy struck Pershing personal life on the night of August 26, 1915. A piece of burning coal slipped out of the fireplace in the house where Pershing was living, at the Presidio in San Francisco. The fire claimed the lives of Helen Frances Warren and their three daughters, but luckily his son Francis Warren Pershing survived. This sad event happened while Pershing and the 8th Brigade was transferring from San Francisco to Fort Bliss in El Paso, Texas. When Pershing returned to San Francisco, he received the tragic news, and saw the remains of his home. Pershing only made one comment: “they had no chance.”

Pershing had no time to mourn his loss, for he had a duty as an officer of the United States Army. Pershing was about to set out upon another military campaign against an elusive foe.25

The Expedition

The Expeditionary forces were composed of the 7th, the 10th, the very same that Pershing served with, the 11th, and the 13th Cavalry regiments, along with the 6th and 16th Infantry regiments and parts of the 6th Field Artillery. They were all supported by engineers and with the novelty equipment of the early twentieth century: automobiles and airplanes of the 1st Aero Squadron. All forces gathered at Columbus and Culberson’s Ranch, New Mexico, causing these mostly quietly settlements to be noisy and crowded with troops, horses, mules, and equipment.26

News reporters also arrived at the staging grounds of the expedition, recording the hustle and bustle of camp life; they harassed high-ranking officers for interviews, as Pershing avoided the best he could as he was busy organizing the operation. Starting on March 14, the expedition marched across the Mexican-American border and into Chihuahua to capture or kill Pancho Villa.27 Yet, the da facto government did not consent for the American armed forces to return into Mexican territory.

As the American airplanes wandered the open sky like vultures searching for Pancho Villa, columns of cavalry and infantry and trucks and cars flowed like a river through the desert. The Americans attempted to use a similar strategy that they had used to subdue the Philippines by controlling the natural geography and local population against the group of bandits. However, in the Philippines, the insurgents were disunified and generally unpopular, but then this was not the Philippines; this was the mountains and deserts of Chihuahua, the backyard of the very popular and unified fighting force of Pancho Villa and the División del Norte.

For over three hundred miles, the American forces searched for Pancho Villa; as they did so, the terrain changed to dirt and sand. Some of the new mechanized vehicles struggled to navigate, and became useless in the mountains. Even the tried and tested horse and mule struggled in the mountains, forcing soldiers to travel on foot. While on the hunt for the División del Norte and to defeat it in a single, decisive battle, the epic clash never came to fruition. Pancho Villa dispersed his force of five hundred into small groups spread across the desert and mountain range. Some even slipped past the American columns and attacked American border towns in Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas.28

Those who remained in Chihuahua fought the Americans in the mountains, valleys, deserts, and villages that dotted the rugged landscape. For over a year, the American forces searched for Pancho Villa, and during that time, dozens of skirmishes broke out, yet only a few had been named: the Battles of Guerrero on March 26, of Parral on April 12, and of Carrizal on June 21. The latter battle was not a clash against División del Norte but with the forces of the Constitutionalist factions due to some unknown reason; most believe that it was because of bad intelligence. The battle resulted in a loss and a strategic miscalculation on the side of the Americans. However, the unwanted attack on the Constitutionalist Army was not a total loss; it strengthened the reputation of the famous Buffalo soldiers of the 10th Cavalry Regiment. A news report highlighted one of the soldiers in the Carrizal Affair, Sergeant Bigstaff, for his bravery in the battle:

“Sergeant Bigstaff might have faltered and fled a dozen times, leaving Adair [his commanding officer] to fight alone, but it never seemed to occur to him he was a comrade to the last blow. When Adair’s broken revolver fell from his hand, the black troop pressed another into, and together, shootin’ in defense. They turned the swoopin’ circle of overwhelming odds before the black man fought in deadly shambles side by side with a white man—following always, fighting always as his lieutenant fought. And finally, when Adair literally shot to pieces fell in his tracks, his last command to his black troop was to leave him and save his own life. Even then, the heroic Negro paused in the midst of that hell. A courage for a final service to his officer, barely a charmed life he’d fought his way out, he saw that Adair had fallen with his head in the water and with superb loyalty, the black trooper turned and went back to the hailstorm of death. He lifted the head of his superior officer out of the water, leaned his [Adair] head against the tree and left him there with dignity when it was impossible to serve him anymore. There is no finer piece of soldierly devotion and heroic comradeship in the history of modern warfare than that of Henry Adair and the black trooper who fought with him at Carrizal.” 29

The battle placed a further strain between the United States and Mexico, the two nations almost sparking a second Mexican-American War. Strangely, the battle could have been avoided for days before the affair at Carrizal. But Pershing and the commander of the Mexican forces in the town, General Trevino, were in respectful communion with one another. General Trevino warned that he had orders to treat any American force that entered the town with force, and Pershing answered that the American soldier would avoid Carrizal. Yet, for reasons unknown to Pershing, even many years later, Captian C. T. Boyd, the American commanding officer, returned to the town, causing the battle to break out.30

Luckily, neither Mexico nor the United States wanted an open war. Hence, as a compromise to avoid war, both governments had to exchange prisoners within ten days of the battle. And the expedition would be turned into a joint operation between the American and Mexican forces to either capture or kill Pancho Villa.31

A New Way of Warfare

Alongside the traditional means of conducting warfare, with cavalry and infantry being supported by artillery, the United States Army utilized some of the newest pieces of technology in the early twentieth century for the first time, by using cars, trucks, and motorcycles on the ground, and airplanes in the sky. Most of the new equipment proved unreliable, due to the lack of spare parts the Americans brought with them. During most of the Mexican Expedition, both the airplane and the vehicles on the ground supported the time-tested means of war.

On one unassuming day, a newly commissioned lieutenant showed motorized vehicles’ potential in future wars while on an errand to buy corn from a local village. That junior officer was 2nd Lieutenant George S. Patton, the temporary aid de camp to Brig. General Pershing. On May 14, 1916, Pershing sent the young Patton and a small unit of ten men from the 6th Infantry and a few Indian Scouts. They took three Dodge Touring Cars, used primarily by high-ranking officers, to the town. While purchasing corn, Patton and the other soldiers decided to travel to the nearby town of San Migelito to see if one of Pancho Villa’s senior officers, Colonel Juilo Cardines, could be found there. Taking the vehicle not meant for direct combat, Patton and troops under his command successfully attacked the ranch, and it became history’s first mechanized raid on a target. Patton later wrote in his journal of the event:

“General Pershing sent me with ten men of the Sixth Infantry, in three autos and scouts Homdohl and Lunt to buy some corn. I was to pay for this corn at the rate of four pesos per hectare. I went to a ranch at Coyote, Rubio and Salsido, where I secured two hundred and fifty hectares of corn. Then I decided to go to the ranch at San Migelito and see if I could not find Colonel Julio Cardines. I found him there and killed him and two of his men and a Captain named Isadore Lopez [and a soldier named Juan Gaza]. We captured five saddles, two rifles, three pistols, two sabres and two belts. The fight started at 10.30 pm and lasted until about 10.45 pm [I personally killed Cardines and Gaza. We all shot at Lopez.]” 27

The raid only lasted for a brief time; it proved a pivotal moment in warfare. It showed that vehicles could be used directly while on campaigns for fast attacks on key enemy locations with a speed that could outpace men on horseback once the technology became more refined, and eventually also becoming armored and armed with machine guns. The use of mechanized units in the Mexican Expedition and the recently introduced tanks found on the Western Front of the Great War influenced many young officers such as the young 2nd Lt. Patton, who was soon to be fighting in Europe. Working with the new tanks and other mechanized tools of war set him on a path to a successful military career from that point onwards.

Result of the Expedition

For months, the American Forces searched for Pancho Villa, but to no avail, for the Mexican people were hiding him and misleading the American forces. All the while, Pancho Villa continued to harass the Americans and hide from them. On one skirmish with the Americans, an unknown soldier shot Pancho Villa in the leg; however, he managed to escape from the battle. Later, a rumor spread that Pancho Villa, Hero of the Mexican People, died from his wounds becoming infected. Yet, the reality was that he did survive but was seriously injured and was hiding in caves in the Sierra Mountain Range for the remainder of the American’s search for him.33

On February 7, 1917, with the discovery of the Zimmermann Telegraph, American troops withdrew across the border as the United States prepared to enter the Great War, ending the Mexican Expedition. Many of the officers and NCOs, including Pershing and Patton, served in the last year of the Great War. They brought with them the knowledge that they had learned during the expedition, from tactics to the limits of new technology and how to repair them when they break down. The military operation under the command of Brig. General Pershing was a successful failure for the United States Army. During the operation that lasted for eleven months, the Americans managed to capture weapons, horses, and defected personnel from the División del Norte.

But it failed to capture or kill Pancho Villa, who continued to wage a guerrilla war against the Constitionalists for many more years, before retiring from military service and settling down in Parral, Chihuahua. Yet, any plans of running for a local political position or even for president and living to old age were abruptly ended when, on July 20, 1923, while traveling down the street in his 1919 Dodge Touring car, someone shouted the words “Viva Villa!” Then, a group of seven armed men shot and killed Pancho Villa, shooting the former bandit and revolutionary with a total of forty bullets meant for big game hunting, two hitting him in the chest and head, killing him instantly. Legend has it that Pancho Villa, who was always quick on the draw of his pistol, managed to pull out his pistol, and with his dying breath, told one of his bodyguards present, “don’t let it end like this. Tell them I said something.” But most believe that he died on the spot without saying a word or grabbing his pistol. The assassination of Pancho Villa was most likely by order of the Mexican government.34

The expedition was a conflict overshadowed by the Great War; it was a conflict of people believing they were doing what was right. The effects of the Mexican Expedition can still be felt even today, from the relationship between the United States and Mexican down to the personal views of individuals on the men who took part in this small chapter of history. Either they were celebrating or denouncing the men who fought in the expedition, from the people who witnessed the event to those who learned it second-handed, from their grandparents and from books.

- Julie Irene Prieto and Roger G. Miller, The Mexican Expedition, 1916-1917 (Army Center of Military History, Washington, D.C., 2016), 15. ↵

- Jeff Guinn, War on the Border: Villa, Pershing, the Texas Rangers, and an American Invasion (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2021), 145. ↵

- Jeff Guinn, War on the Border: Villa, Pershing, the Texas Rangers, and an American Invasion (Simon and Schuster, 2021), 145. ↵

- Eileen Welsome, The General and the Jaguar: Pershing’s Search for Pancho Villa: A True Story of Revolution and Revenge (Little Brown, 2009), 97. ↵

- Julie Irene Prieto and Roger G. Miller, The Mexican Expedition, 1916-1917 (Army Center of Military History, Washington, D.C., 2016), 18. ↵

- John Joseph Pershing, My Experiences In The World War – Vol. I (Illustrated Edition) (Pickle Partners Publishing, 2014), 334. ↵

- Haldeen Braddy, “The Faces of Pancho Villa,” Western Folklore 11, no. 2 (1952): 93, https://doi.org/10.2307/1496836. ↵

- Haldeen Braddy, “The Faces of Pancho Villa,” Western Folklore 11, no. 2 (1952): 93, https://doi.org/10.2307/1496836. ↵

- Haldeen Braddy, “The Faces of Pancho Villa,” Western Folklore 11, no. 2 (1952): 94, https://doi.org/10.2307/1496836. ↵

- Haldeen Braddy, “The Faces of Pancho Villa,” Western Folklore 11, no. 2 (1952): 94, https://doi.org/10.2307/1496836. ↵

- Mexico Unexplained, “The Border Wars, 1910-1919: Mexico Unexplained,” posted on February 11, 2018, YouTube video, 17:09, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9w7cjWgrwSE. ↵

- Haldeen Braddy, “The Faces of Pancho Villa,” Western Folklore 11, no. 2 (1952): 98, https://doi.org/10.2307/1496836. ↵

- Smithsonian Magazine and Mike Dash, “Uncovering the Truth Behind the Myth of Pancho Villa, Movie Star,” Smithsonian Magazine, accessed March 16th, 2022, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/uncovering-the-truth-behind-the-myth-of-pancho-villa-movie-star-110349996/. ↵

- “$160,000 in 1913 → 2022 | Inflation Calculator,” accessed March 16, 2022, https://www.in2013dollars.com/us/inflation/1913?amount=160000. ↵

- Kathlene Scalise, “Surprising New Information on Pancho Villa Comes to Light in Obscure Wells Fargo Files at UC Berkeley,” accessed March 16th, 2022, https://www.berkeley.edu/news/media/releases/99legacy/5-3-1999.html. ↵

- John Joseph Pershing, My Experiences In The World War – Vol. I (Illustrated Edition) (Pickle Partners Publishing, 2014), 336. ↵

- John Joseph Pershing, My Experiences In The World War – Vol. I (Illustrated Edition) (Pickle Partners Publishing, 2014), 336-337. ↵

- John Joseph Pershing, My Experiences In The World War – Vol. I (Illustrated Edition) (Pickle Partners Publishing, 2014), 36. ↵

- John Joseph Pershing, My Experiences In The World War – Vol. I (Illustrated Edition) (Pickle Partners Publishing, 2014), 51. ↵

- John Joseph Pershing, My Experiences In The World War – Vol. I (Illustrated Edition) (Pickle Partners Publishing, 2014), 75. ↵

- “Moro | People | Britannica,” accessed March 23rd, 2022, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Moro. ↵

- “Moro Wars | Philippine History | Britannica,” accessed March 24th, 2022, https://www.britannica.com/event/Moro-Wars. ↵

- “John J. (Black Jack) Pershing | Biography, Facts, & Nickname | Britannica,” accessed March 28th, 2022, https://www.britannica.com/biography/John-J-Pershing. ↵

- John Joseph Pershing, My Experiences In The World War – Vol. I (Illustrated Edition) (Pickle Partners Publishing, 2014), 317-319. ↵

- Mailing Address: Fort Mason et al., “John Pershing – Success and Tragedy – Presidio of San Francisco (U.S. National Park Service),” accessed March 29th, 2022, https://www.nps.gov/prsf/learn/historyculture/john-pershing.htm. ↵

- “Mexican Expedition Campaigns | U.S. Army Center of Military History,” accessed April 1st, 2022, https://history.army.mil/html/reference/army_flag/mexex.html. ↵

- “Image 1 of George S. Patton Papers: Diaries, George S. Patton 1910-1945; Annotated Transcripts; 1916,” online text, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA, accessed January 31st, 2022, https://www.loc.gov/resource/mss35634.00202/?sp=1&st=text. ↵

- Historic Films Stock Footage Archive, UNITED STATES VS. MEXICO – THE PURSUIT OF PANCHO VILLA 1916, posted on May 25, 2018, Youtube Video 6:43, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=byL6QIDRY6o. ↵

- LionHeart FilmWorks, The United States Cavalry – 1916 Mexico Punitive Expedition – A History, posted on September 26, 2019,10:45, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vkuewszQ62Q. ↵

- John Joseph Pershing, My Experiences In The World War – Vol. I (Illustrated Edition) (Pickle Partners Publishing, 2014), 461. ↵

- Jeff Guinn, War on the Border: Villa, Pershing, the Texas Rangers, and an American Invasion (Simon and Schuster, 2021), 214. ↵

- “Image 1 of George S. Patton Papers: Diaries, George S. Patton 1910-1945; Annotated Transcripts; 1916,” online text, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA, accessed January 31st, 2022, https://www.loc.gov/resource/mss35634.00202/?sp=1&st=text. ↵

- “Pancho Villa’s Death Reported in 1916… – RareNewspapers.Com,” accessed April 19, 2022, https://www.rarenewspapers.com/view/223400.. ↵

- Christopher Minster, “Who Really Killed Mexican Warlord Pancho Villa?,” ThoughtCo, accessed April 19, 2022, https://www.thoughtco.com/who-killed-pancho-villa-2136687. ↵

3 comments

Eugenio Gonzalez

This article provided both information and a thoroughly enjoyable reading experience. I appreciated how the author took pauses to provide enough backstory, allowing readers to understand the connections between characters, places, and events. The details about Francisco “Pancho” Villa helped me understand why people in poverty regarded him as a respectable figure. Learning about his initiatives such as creating schools, programs for widows protection, and other sources of aid was enlightening and something I wasn’t aware of before.

Victoria Cantu

A very descriptive and detailed article! I enjoyed reading the historical unfolding of what led to the Mexican revolution and the result of this expedition. Growing up in a Mexican household, I’ve always heard about the stories of Pancho Villa and how more diminutive towns and poverty-stricken villages praised Pancho Villa for his attentive actions to help the poor. The details about Fransisco “Pancho” Villa help me conclude why people of poverty saw him as a respectable man. Reading about how he created schools, programs to protect widows, and offered more sources of help was something I was unaware of as well. Overall, I loved the effort put into this article, diving into who was involved in this expedition, and the results were fascinating to read about!

Richard Huber

This article was an informative and thoroughly enjoyable read. I loved how the author paused to give enough backstory to allow the reader to understand how the characters , places and events are linked. You can see how the reasons for warfare may not change much; But , advances in technology , travel, armaments and communications change how warfare can be carried out…It was fascinating to see that Pershing was motivated to seek out the Cavalry because he saw that as “where the action was”…..Pershing was connected with Buffalo Soldiers in the Dakotas , Teddy Roosevelt , Gen. Arthur McArthur In the Philippines , Gen. George Patton in Mexico and France….The author points out that history isn’t just singular events connected by a time line….. History is a series of places and events connected by an evolution of people and changing technologies…..