American forces patrolled humid dense jungles, hunting for insurgents. With that image, some would assume that we were talking about Vietnam. However, that is not the case; this is only a glimpse into one of America’s Forgotten Wars. It was the Philippine-American War, one of the few wars of American Imperialism. The war directly resulted from the “Splendid Little War,” also known as the Spanish-American War. This Philippine conflict was one that the United States inherited from the Spanish Empire, but it cost America so many more lives than the Spanish-American War; this relatively unknown Philippine-American War officially lasted from 1899 to 1902 but continued, through other rebellions and uprisings, until 1911. But it sealed the United States’ position in the world as a world power. Despite the length of the conflict, it proved to be one of, if not the most successful, counterinsurgency operations in the almost two-hundred-fifty-year history of the United States.

How, you may ask, did the American Armed Forces successfully defeat the Philippines in combat? The War Department employed a strategy with three critical factors that brought them victory. The first strategy was for the Americans to isolate the insurgents from possible support in supplies, troops, and information. The second was to keep a unit of soldiers in the exact location for the men to provide the commander with knowledge of the local condition, from geological features to the local opinion. And then, the American Forces used the Philippines’ human geography and diversity against the rebels.

The Filipinos had been fighting for independence since the death of Jose Rizal, who was a writer who advocated colonial reforms and was shot and killed for sedition on December 30th, 1896—sparking a revolution that the larger Spanish-American War would engulf on the horizon.1 Before the war, the United States started to support the independence movements in the Philippines and Cuba out of sympathy for their cause of gaining independence from a European country. The United States also hoped that they might see economic opportunity with these newly sovereign nations. At the same time, the Spanish continued to press down on the revolutionaries. During the Cuban Revolution, the United States sent down one of the most potent ships at its disposal, the USS Maine. Both Spain and the United States wished for an excuse to engage one another directly, and that opportunity came with the USS Maine incident.2

While docked in Havana Harbor, a fire broke out below deck and detonated the USS Maine’s forward magazine, and the ship subsequently sunk from the resulting explosion. However, the media and Congress’s investigation claimed that it was a Spanish sea mine attack. The subsequent conflict between the Spanish and the Americans was composed in two significant theaters: Cuba and the Philippines. Before the outbreak of the war, the United States partly mobilized the Asiatic Squadron under the command of Commodore Dewey. Then after several weeks of attempting a peaceful solution on both sides, Spain declared war on the United States on April 24th, 1898, and a day later, the United States did likewise.

In the early morning of May 1st, 1898, the American Squadron steamed into Manilla Bay with no opposition. The squadron set out from Mris Bay near Hong Kong and towards Manila Bay when the Spanish-American War was declared. The Spanish Pacific Fleet was anchored in Manila Bay. It had twice as many fighting ships as the American forces. However, the American ships were much more heavily armed and armored than the Spanish forces when the Americans struck against the Spanish early in the morning while still in port.3

During the naval engagement, the Filipino Revolutionaries were also fighting Spanish forces. Its only significant theater of engagement was the Battle of Manila Bay at its climax. The Spanish Pacific Fleet was utterly destroyed with heavy losses, while the Americans received relatively light casualties and lightly damaged ships at the battle’s conclusion. The Spanish governor surrendered the entire country to Commodore Dewey; however, he did not have the resources to hold the Philippines. Furthermore, on June 12th, the Filipinos fully declared independence, formed the First Philippine Republic, and voted for their revolutionary leader, Emilio Aguinaldo as its first president.4

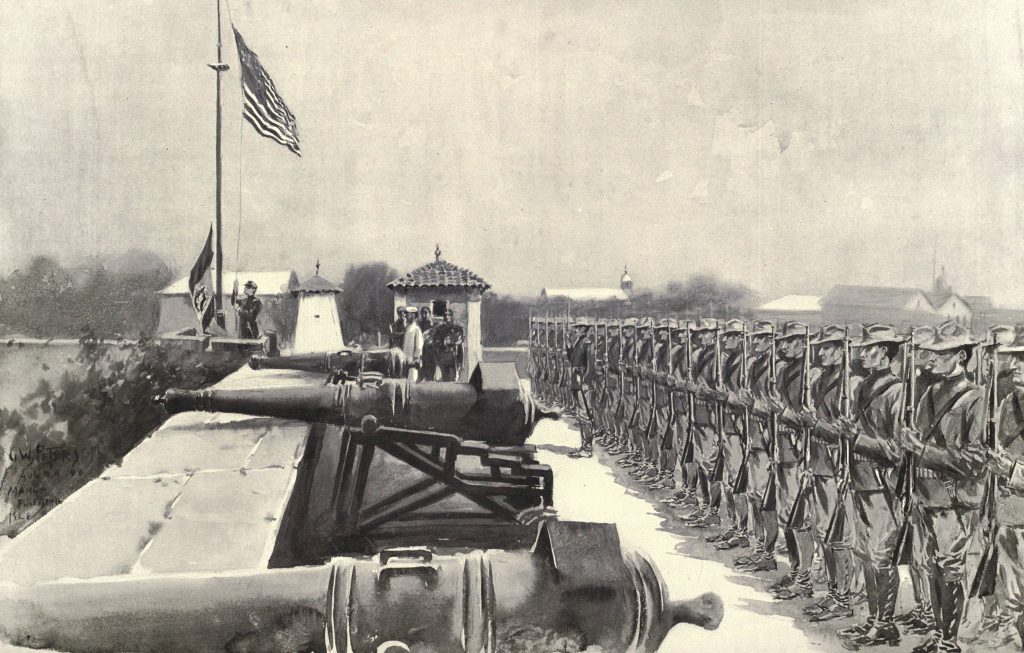

Spanish reinforcements arrived in the Philippines on August 13th, 1898. The final battle of the Spanish American War then took place. The clash resulted in nine Americans and forty-nine Spaniards losing their lives, marking the end of Spanish Colonial holdings in Asia. However, the conflict was a play, and Manila Bay was the stage. A few days before the battle, Major General Merrit, Rear Admiral Dewey, and Brigadier General MacArthur, the father of Douglas MacArthur, met with the Spanish Governor-General of the Philippines, Fermín Jáudenes y Álvarez. There the high-ranking officials decided to script an honorable defeat by staging a battle to symbolize the end of Spanish rule and the transfer of power.5

The Spanish and the Americans agreed to the scripted battle; however, the Filipino revolutionaries were unaware of the plan. In the eyes of the colonial powers in Europe and of the newly recognized global authority of the United States, it was better to lose a colony to another colonial power than to lose it to the local population. The stage for the scripted battle was at Fort Santiago, and on one side were the Spanish Colonial forces, while on the other side were the combined forces of the Americans and the Filipinos. The relationship between the Americans and the Filipinos started to wane while on the road to Manilla because Major General Merrit would not allow the revolutionaries to march along with the U.S. soldiers as they marched to the capital of the Philippines. The Americans seized control of Manila while the revolutionaries seized the remainder of the archipelago.

The war concluded with the signing of the Treaty of Paris (1898). Spain transferred the sovereignty of the Philippines to the United States, ignoring the local population, even though the Philippine Republic controlled all but Manila. The Philippine Republic agreed to the terms in the Treaty of Paris, except for the United States holding sovereignty over the Philippines. While on the other side of the table, the United States did not recognize the Philippines’ claims of independence. The United States practiced a direct form of imperialism for two particular reasons: the Americans desired to have a foothold in the Asian economies, such as the rapidly industrializing Japanese Empire and the Chinese trade. The second reason was a product of the era of imperialism, of the so-called “white man’s burden.” The Americans did not believe that the Filipinos were ready to govern themselves or defend themselves from other colonial powers, such as Japan or Germany.6

Naturally, the relationship between the Americans and the Filipinos soured, and tensions grew on the night of February 4th, 1899. Pvt. William W. Grayson and Pvt. Miller of the Nebraska Volunteer Infantry Regiment was on guard duty at their camp entrance. The Filipinos were making their thoughts about the United States’ control over the archipelago clear. Pvt. William W. Grayson later wrote down in his diary the following:

“About eight o’clock, Miller and I were cautiously pacing our district. We came to a fence and were trying to see what the Filipinos were up to. Suddenly, near at hand, on our left, there was a low but unmistakable Filipino outpost signal whistle. It was immediately answered by a similar whistle about twenty-five yards to the right. Then a red lantern flashed a signal from blockhouse number seven. We had never seen such a sign used before. In a moment, something rose up slowly in front of us. It was a Filipino. I yelled Halt! and made it pretty loud, for I was accustomed to challenging the officer of the guard in approved military style. I challenged him with another loud halt! Then he shouted “halto!” to me. Well, I thought the best thing to do was to shoot him. He dropped. If I didn’t kill him, I guess he died of fright. Two Filipinos sprang out of the gateway about fifteen feet from us. I called halt! and Miller fired and dropped one. I saw that another was left. Well, I think I got my second Filipino that time.”7

The U.S. soldiers killed at least two Filipino soldiers; however, some Filipino historians claimed that the killed soldiers were unarmed. Regardless of the details, the action resulted in the Battle of Manilla that lasted until the next day. The battle of Manilla became the largest and one of the few conventional battles during the war involving fifteen-thousand Filipino militiamen. In comparison, the United States forces were composed of nineteen-thousand soldiers.8

During the Battle of Manila, Aguinaldo said that he was willing to order a ceasefire to the commanding General Otis. Yet, Otis declined, and thus the opening Philippine-American fighting raged until the morning of the next day. During this time, Aguinaldo was now the leader of the self-proclaimed independent Republic of the Philippines. The following was his address to the world:

“To All Civilized Nations and Especially to the Great North American Republic.

Spain maintained control of the Philippine Islands for more than three centuries and a half, during which period the tyranny, misconduct and abuses of the Friars and the Civil and Military Administration exhausted the patience of the natives and caused them to make a desperate effort to shake off the unbearable galling yoke…

…

The Commander urged me to return to the Philippines to renew hostilities against the Spaniards with the object of gaining our independence, and he assured me of the assistance of the United States in the event of war between the United States and Spain.

…

When the Spaniards ran out of ammunition and surrendered, with all their arms, to the Filipino Revolutionists, who took their prisoners to Cavite. In commemoration of this glorious achievement I hoisted our national flag in presence of a great crowd, who greeted it with tremendous applause and loud, spontaneous and prolonged cheers for “Independent Philippines” and for “the generous nation”—the United States of America.

This glorious triumph was merely the prelude to a succession of brilliant victories, and when the May 31st came—the date fixed for general uprising of the whole of the Philippines—the people rose as one man to crush the power of Spain.

…

In the course of official business General Anderson solemnly and completely endorsed the promises to me, asserting on his word of honour that America had not come to the Philippines to wage war against the natives nor to conquer and retain territory, but only to liberate the people from the oppression of the Spanish Government.

…

I, Emilio Aguinaldo—though the humble servant of all, am, as President of the Philippine Republic, charged with the safeguarding of the rights and independence of the people who appointed me to such an exalted position of trust and responsibility—mistrusted for the first time the honour of the Americans … no other course was open to me but to repel with arms such unjust and unexpected procedure on the part of the commander of friendly forces.

…

I need not dwell on the cruelty which, from the time of the commencement of hostilities, has characterized General Otis’s treatment of the Filipinos, shooting in secret many who declined to sign a petition asking for autonomy. I need not recapitulate the ruffianly abuses which the American soldiers committed on innocent and defenseless people in Manila, shooting women and children simply because they were leaning out of windows; entering houses at midnight without the occupants’ permission—forcing open trunks and wardrobes and stealing money, jewelry and all valuables they came across…

…

Are we, perchance, less deserving of liberty and independence than those revolutionists? Oh, dear Philippines! Blame your wealth, your beauty for the stupendous disgrace that rests upon your faithful sons. You have aroused the ambition of the Imperialists and Expansionists of North America and both have placed their sharp claws upon your entrails!

…

So I trust in the rectitude of the great people of the United States of America, where, if there are ambitious Imperialists, there are defenders of the humane doctrines of the immortal Monroe, Franklin, and Washington; unless the race of noble citizens, glorious founders of the present greatness of the North American Republic, have so degenerated that their benevolent influence has become subservient to the grasping ambition of the Expansionists…

…

Distressing, indeed, is war! Its ravages cause us horror. Luckless Filipinos succumb in the confusion of combat, leaving behind them mothers, widows and children. America should not continue a war in contravention of their honourable traditions as enunciated by Washington and Jefferson.

…

The veracity of these facts rests upon my word as President of this Republic and on the honour of the whole population of eight million souls, who, for more than three hundred years have been sacrificing the lives and wealth of their brave sons to obtain due recognition of the natural rights of mankind—liberty and independence.”9

During the first phase of the war, which lasted for a few months, Aguinaldo attempted to wage a conventional war against the American forces from February to November. However, the American troops were better trained and equipped, causing the conflict to become a guerrilla war. The war officially ended when the United States captured Aguinaldo in 1901, ending the second phase of the war, which was then formally completed in 1902. The conflict continued through many independent movement uprisings, and rebellions sprouted across the archipelago on a micro level until 1911. The Philippines, as an archipelago, consists of over seven and a half thousand islands. This physical feature has both an advantage and a hindrance for both the attacker and the defender.

As stated by Dr. Joseph McCallus, “The Philippian Army hoped that in these new settings, tropical disease, impassable roads, and unfamiliar conditions would weaken the American advance, while the geographic knowledge the village-level support should sustain guerrilla ambushes and surprise attacks against isolated American patrols.”10

The Philippines, with almost eight thousand islands densely jungled, is separated by vast amounts of water. It was a country that seemed ideal to wage an asymmetric war against an invading force. However, the same features that would provide a significant advantage could also be a disadvantage. The Philippines’ geography allowed the United States Navy to isolate the Filipino insurgents in Marinduque, Samar, Cebu, Batangas (South of Manila), and Ilocos Regions (Northwest region of Luzon). Suppose one would look at a map of the Philippines with the aforementioned regional hotspots. One would notice that the rebelling hotspots were easily isolated because they were either an island or had physical features such as mountains and dense forests separating them. However, using such a strategy can easily backfire if not executed properly. During the Philippine-American War, the United States Navy played a crucial role in keeping the conflict to regional rebellions rather than letting it escalate to a national revolution.

The American forces took advantage of a weakness, much like the Romans surrounded the Zealots in Masada’s fortress with their legions. That is what the Americans did with their Navy, by controlling the waters of the Philippines. This act was crucial in keeping the conflict contained; otherwise, the war would most likely have favored the Philippian Army. The command over the waterways allowed the American forces to isolate the Filipino insurgent island strongholds. The Americans severed the resistance movements from reinforcements and established other operations while also denying the insurgents aid and support, both foreign and domestic, while efficiently supplying the American forces. President Aguinaldo’s book, A Second Look at America, states, “with the American Navy blockading our country, the trickle of foreign arms would completely stop.”11

The Philippines proved to be an ideal region to blockade; the United States Navy was able to take control over the inter-island trade and the means to move troops effectively from island to island. The U. S. Navy also maintained a constant patrol by gunboats and armed shallow-drafted vessels for riverine operations. The control of the waterways in the Philippines allowed the Americans to exploit the fragmented land of the Philippines, either wholly or nearly isolating the rebel forces in the regions. The near-constant patrols prevented even smugglers from supplying the rebel garrisons with food, intelligence, weapons, and ammunition—an example of how effective the navel operation was with the rebel force on Marinduque.

As stated by Ted W. Carlson from the Naval Postgraduate School in his thesis paper wrote, “It struck at the crucial necessities of the insurgency: inter-island communications, operations, supplies, and finances. By severing waterborne traffic, the Navy isolated each island’s resistance movement and prevented the transfer of reinforcements and the establishment of sanctuaries.”12 The United States Navy patrolled the waters of the Philippines, preventing the Filipino rebels from receiving supplies, inter-island travel, and their escape from their holdings. The Navy also provided inter-island travel for the American forces, which allowed them to avoid dense vegetation and mountains, promptly allowing movement of their troops.

The United States Army conducted search-and-destroy operations deep within the hotspots. These operations consisted of American forces entering a rebel-occupied area to capture or kill rebels and disrupt enemy movements and operations before returning to friendly territory and settlements such as Manila. The American Army, after each operation, did not attempt to hold captured territory, and that allowed the Filipino insurgents to regain the land, thus beginning a cycle that lasted from November 1899 to March 1900.13

The War Department was not pleased with a situation that resembled Sisyphus’s punishment for his attempt to cheat death, where he had to roll a boulder up a hill for eternity. Every time he neared the top of the mountain, the boulder would roll back down. The War Department decided to reorganize the campaigning forces into the Military Division of the Philippines, dividing it into four departments: Northern Luzon, Southern Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao. These departments presided over the smaller districts and their garrisons.14

The War Department primarily stationed units in garrisons and districts. This change of strategy allowed the American soldiers to become familiar with the terrain and the local population. These garrisons also benefited from this change of strategy, for they were authorized to act with more autonomy. Most forts were in remote areas, cutting them off from Manila and the higher echelons.15

In his article, “Lessons from a Successful Counterinsurgency: The Philippines, 1899-1902,” Thomas K. Deady states:

From 53 garrisons in May 1900 when General Otis departed, American presence had expanded to over 500 by the time Aguinaldo’s capturing. Largely isolated from higher-echelon control, small garrisons lived and worked in the local communities. They tracked and eliminated insurgents, built reports with the populace, gathered intelligence, and implemented civil works. The process was slow, but once an area was pacified, it was effectively denied to the insurgency.16

The garrison commanders took the liberty of living among the local population, where they could create tactics and methods to counter the insurgencies in the area. Over the extended time in one location, the American troops were able to identify and separate those who were actively resisting from those who were not. An example of this new strategy and its success was with Lieutenant William Johnston and his garrison near Bauang in the Ilocos Region of Luzon. The town’s mayor turned over Crispulo Patajo, a local resistance group leader. While interrogating the rebel group leader, Patajo divulged information that the mayor was also a member of the town’s relationship with the rebel group, supporting them and protecting them from the American forces. The Americans could confirm the information from the persecuted minority and then destroy the guerrilla infrastructure.17

The new Tactical Operations Systems greatly enhanced the accuracy of the military intelligence division. A unit recently commissioned by Maj. Gen. Arthur MacArthur assumed command of the American forces in the Philippines. The isolation of rebel groups and the placement of American troops were essential in containing the insurrection from spreading nationwide. Nevertheless, what kept the Filipinos from unifying into a singular force with one goal was the diversity of the Philippines, a natural result of the geography of the Philippines. There were nearly 181 spoken languages in the archipelago during the conflict, with no unifying language, including Spanish. The Philippines is home to almost two hundred ethnolinguistic groups, including indigenous Muslims, non-indigenous Muslims, and non-indigenous non-Muslim groups.18

An example of the ununified nature that the Republic of the Philippines faced was with the Tagalogs people, one of the most dominated ethnic groups in the Philippines and one of the main contributors to the Philippine-American War. However, the Tagologs were a disliked ethnic group by the indigenous and non-indigenous peoples alike. An example of their disliking of the Tagologs people was when Aguinaldo assigned General Ananias Diocno, a Tagologs, to Panay, a region in upper Luzon, to rally the local population. But the local population was predominately a part of the Ilonggos people. While General Ananias Diocno was on his mission, most of the local population ignored or were openly hostile to him, and those who joined Aguinaldo’s cause reused the order given by the general and himself.19

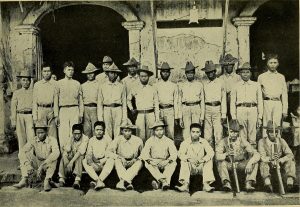

The United States Military exploited this trait to its full advantage by recruiting many ethnic groups who were traditionally enemies with the Tagalogs. Once assuming command of the Philippine division, Gen. MacArthur employed an old tactic that the United States used during the Indian Wars. It was not uncommon for the American Army to make alliances with a Native American tribe’s rivals. In the French and Indian War, the American colonial militias and the British regulars used their Native American allies to counter the tribes who sided with the French, such as the Wabanaki Confederacy.20

Gen. MacArthur enlisted the help of pro-American Filipinos as scouts and intelligence gatherers. One such pro-American force was the Kingdom of Macabebe, located in the Pampanga Province in Luzon. This ethnic group had a history of serving the Spanish government to control the archipelago for over three hundred years. The Mecabebes, as a reward for their loyalty, received greater privileges than the other ethnic groups, causing tension between them and the different ethnic groups. In exchange for their three-hundred years of service, the Spanish forces in the Philippines used them as scouts.21

However, the Macabebes allegiance changed in June 1898 when the Spanish forces abandoned the town that the Macabebes called home and the Filipino revolutionaries shortly captured it. The revolutionaries burned and plundered Macabebe and executed many captured soldiers. As armed scouts of the Philippine Division, they served in the home province and district, proving vital in many battles between the American forces and the rebels. The Macabebes and many other pro-American Filipinos allowed the American land and sea forces to understand the local languages, customs, and terrain. By organizing over five thousand Filipinos and the Manilla police force as scouts and informers, by June 1901, the Army had authorized that number to double as part of the Division of Military Information.22

The Philippine-American War devolved into a series of rebellions by various ethics groups, only ending in 1913 with the defect of the Moro People, using a combination of U.S. Cavalry and pro-American Filipino forces. And the United States held sovereignty over the Philippines until after the Second World War. Most of the history of the Philippines, from the Early Modern Period to the twentieth century, was governed by foreign countries such as the Spanish Empire. Then the United States inherited the former Spanish colony without the consent of the Filipinos. The tension between the Philippines and the United States quickly boiled over into a war. The Philippine-American war was the most prolonged conflict the United States fought before the War on Terror.

When the war started, the Filipino armed forces attempted to fight a conventional war. However, the Americans were better armed and trained, which forced the Filipino Army to fall back into isolated locations in the densely jungled islands, hopefully using the Philippines’ natural geography against the Americans. Yet, the war proved to be one of the most successful counterinsurgency operations the United States had ever launched. From the outbreak of the war in Manilla to the final shot in the Moro Province, the United States used the Philippines’ natural and human geography against the Filipino forces, an old Indian-fighting tactic. The Marines and Army were sent to search and destroy Filipino forces and set garrisons in villages and towns by dividing, isolating, and laying siege via effective blockades. With the benefit of being isolated by higher commands, the garrison commanders could adjust accounting to counter the insurgents in the area. These three actions allowed the American forces victory over the Filipinos during the conflict.

- “Philippine-American War | Facts, History, & Significance,” Encyclopedia Britannica, accessed October 21st, 2021, https://www.britannica.com/event/Philippine-American-War. ↵

- “Memories of the Loss of the USS MAINE,1898,” accessed October 26th, 2021, https://www.spanamwar.com/mainelos.htm. ↵

- George Dewey, “Admiral George Dewey’s Report of the Battle of Manila Bay (Cavite), 1898,” The Spanish American War (website), accessed March 30th, 2022, https://www.spanamwar.com/dyreport.htm. ↵

- “Emilio Aguinaldo | Biography, Facts, Significance, & Spanish-American War | Britannica,” Encyclopedia Britannica (online), accessed March 30th, 2022, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Emilio-Aguinaldo. ↵

- “Mock Battle, Real Betrayal,” Manila Bulletin, August 18th, 2020, https://mb.com.ph/2020/08/18/mock-battle-real-betrayal/. ↵

- “The Philippines, 1898–1946 | U.S. House of Representatives,” History, Art & Archives (website), accessed March 28th, 2022, https://history.house.gov/Exhibitions-and-Publications/APA/Historical-Essays/Exclusion-and-Empire/The-Philippines/. ↵

- “Written Accounts – Philippine American War,” accessed October 5th, 2021, https://blogs.baylor.edu/philippineamericanwar/document-page-3/. ↵

- “Battle of Manila | Summary | Britannica,” Encyclopedia Britannica, accessed March 28th, 2022, https://www.britannica.com/event/Battle-of-Manila-1899.. ↵

- “Written Accounts – Philippine American War,” accessed October 5th, 2021, https://blogs.baylor.edu/philippineamericanwar/document-page-3/. ↵

- William N. Holden, “The Role of Geography in Counterinsurgency Warfare: The Philippine American War, 1899–1902,” GeoJournal 85, no. 2 (April 1st, 2020): 423–37, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-019-09971-7, 429. ↵

- William N. Holden, “The Role of Geography in Counterinsurgency Warfare: The Philippine American War, 1899–1902,” GeoJournal 85, no. 2 (April 1st, 2020): 423–37, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-019-09971-7, 429. ↵

- Ted W. Carlson, THE PHILIPPINE INSURRECTION: THE U.S. NAVY IN A MILITARY OPERATION OTHER THAN WAR, 1899-1902, Naval Postgraduate School (December 2004): 50, https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA429668.pdf. ↵

- Ted W. Carlson, THE PHILIPPINE INSURRECTION: THE U.S. NAVY IN A MILITARY OPERATION OTHER THAN WAR, 1899-1902, Naval Postgraduate School (December 2004): 50.https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA429668.pdf. ↵

- Ted W. Carlson, THE PHILIPPINE INSURRECTION: THE U.S. NAVY IN A MILITARY OPERATION OTHER THAN WAR, 1899-1902, Naval Postgraduate School (December 2004): 91, https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA429668.pdf. ↵

- Thomas K. Deady, “Lessons from a Successful Counterinsurgency: The Philippines, 1899-1902,” The US Army War College Quarterly: Parameters 35, 1 (2005): 57, https://press.armywarcollege.edu/parameters/ vol35/iss1/4. ↵

- Thomas K. Deady, “Lessons from a Successful Counterinsurgency: The Philippines, 1899-1902,” The US Army War College Quarterly: Parameters 35, 1 (2005): 57, https://press.armywarcollege.edu/parameters/ vol35/iss1/4. ↵

- Celia M. Reyes et al., “Inequality of Opportunities among Ethnic Groups in the Philippines,” 154th ed., vol. 2017, WIDER Working Paper (UNU-WIDER, 2017), 6, https://doi.org/10.35188/UNU-WIDER/2017/380-6. ↵

- William N. Holden, “The Role of Geography in Counterinsurgency Warfare: The Philippine American War, 1899–1902,” GeoJournal 85, no. 2 (April 1st, 2020): 430, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-019-09971-7. ↵

- Allan R Millett and Peter Maslowski, For the Common Defense: A Military History of the United States of America (New York: Free Press, 1994), 274. ↵

- Allan R. Millett and Peter Maslowski, For the Common Defense: A Military History of the United States of America (New York: Free Press, 1994), 274. ↵

- Amber Tarnowski, “Macabebes and Moros,” www.army.mil, accessed November 24, 2021, https://www.army.mil/article/40345/macabebes_and_moros. ↵

- “Macabebes and Moros,” www.army.mil, accessed November 24, 2021, https://www.army.mil/article/40345/macabebes_and_moros. ↵

7 comments

Eugenio Gonzalez

The article was informative, with a compelling narrative that maintains the reader’s attention with the development of the war. I liked the author’s cover image as it helps the reader be more intrigued by the article. I also liked how the author explains the conflict making it more understandable for readers. Overall, it was an excellent article, and I learned about a conflict that lasted three years.

Dylan Vargas

The article is very well done and put together very nicely, I like the different sections like the one that highlights Aguinaldo. The way the author highlights the quote and what it means is also very well done. The story is very put together nicely and gives us the details to fill us in on the whole thing. the story is also very important to Asian and American history so I am glad it is being told.

Vianne Beltran

Hi Seth,

I enjoyed your article as the Philippine-American war does seem forgotten compared to other historical wars. The impact of it is not inconsequential though. I did not know that more Americans died in this war than even the Spanish-American war. It’s crazy that the Spanish were so prideful that they had to script the final battle. It makes sense seeing as they would have rather lost its colony to another superpower rather than the colonies’ natives.

Paula Ferradas Hiraoka

Hello Seth,

First of all, congratulations on your nomination and getting your article published!

The use of pictures in this article looks beautiful and makes a perfect mix with the article. I think this article has a lot of information but it’s a really summarized information. I also found it helpful that you carefully explained the nuances of a topic that seems complex at first glance and made it easy to understand.

Overall, good work and good luck!

Madison Goza

Cool cover image! The art style really caught my attention – great use of images throughout! I appreciate how you clearly outlined the factors that contributed to an American victory in the conflict. I also found it helpful that you carefully explained the nuances of a topic that seems complex at first glance and made it easy to understand. Overall, very well-researched and well-written article! Great job!

Carlos Hinojosa

It’s very interesting to see the many wars that people seem to forget that we were a part of. Like the Korean war, the Mexican American war, the War of 1812, Gulf war and of course the Philippines-American war. All of them important in their own right but will always get overshadowed by the bigger wars that were around the same time periods. This article did amazing job showing the importance of this article. Good job, hope to read more from you.

Richard Huber

Amazing article that provides so much information about a conflict that had lasted a mere 3 years . I was not aware of so much of what the author presented ; And, presented in a way that leads me to try to link the historical content in multiple directions. It was a historical account of a conflict ; but , It also contains Military Theory and Battle Strategies. I loved the analogies to the protection forts that guarded the trail routes to allow settlers to safely migrate westbound as the United States expanded…and inter action with natives then in the west compared to interacting with indigenous Filipino. It was amazing that so much was. Accomplished between 1899 and 1902 in organizing and implementing an effective strategy that worked….. a similar strategy in the old west resulted in catastrophic Battle of little Big Horn…Similar strategy didn’t work well in Viet Nam with more resources and more men

available. The Operation shows tremendous cooperation between the Navy and Army ground forces… something that would not happen again until deep into WWll….Teddy Roosevelt had just been Secretary of Navy in 1897 , then Vice President , Then Succeeded as President during this period? When you combine the resources of Men, Material and Money; Maybe the measure of the man is most meaningful….